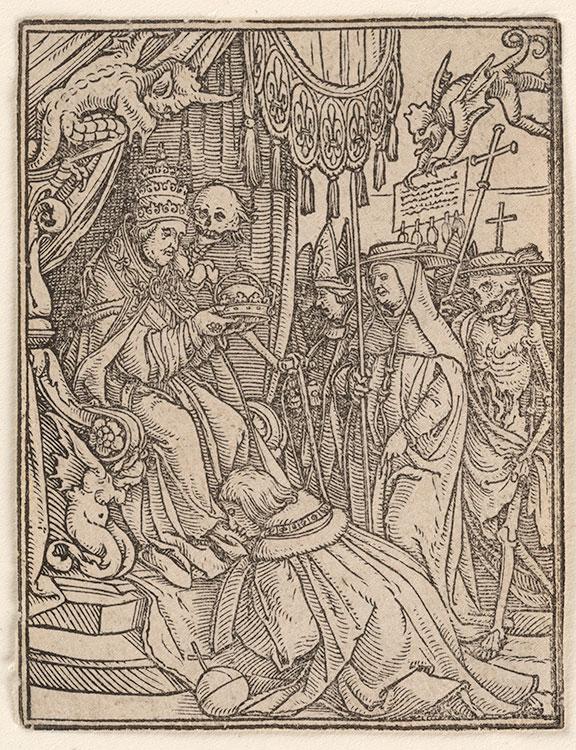

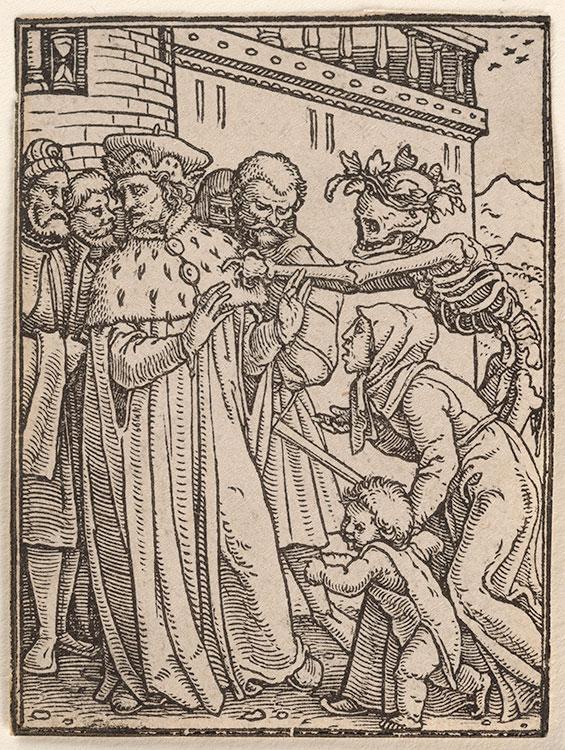

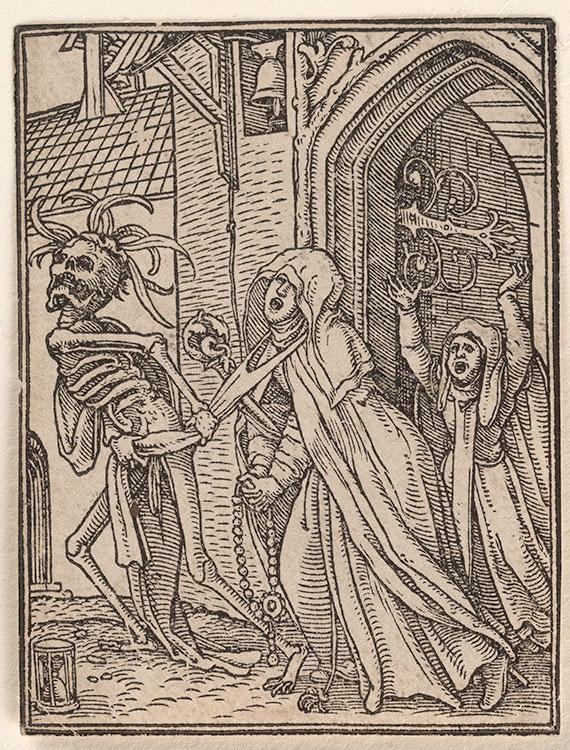

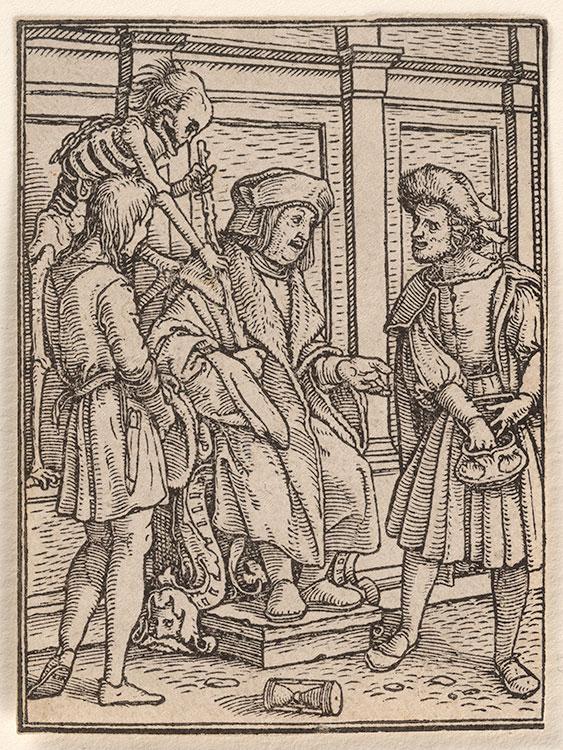

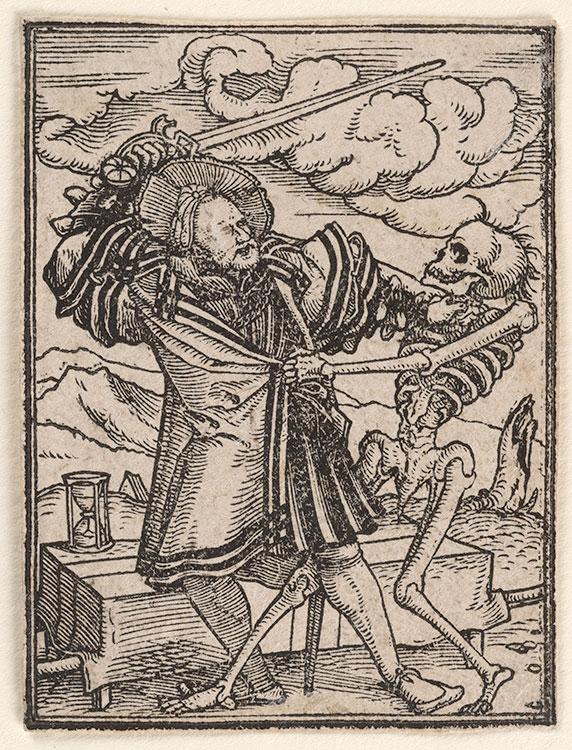

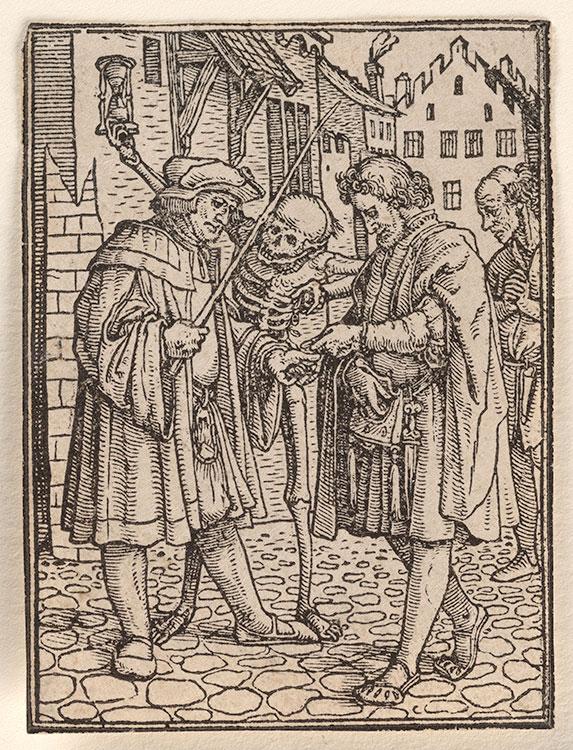

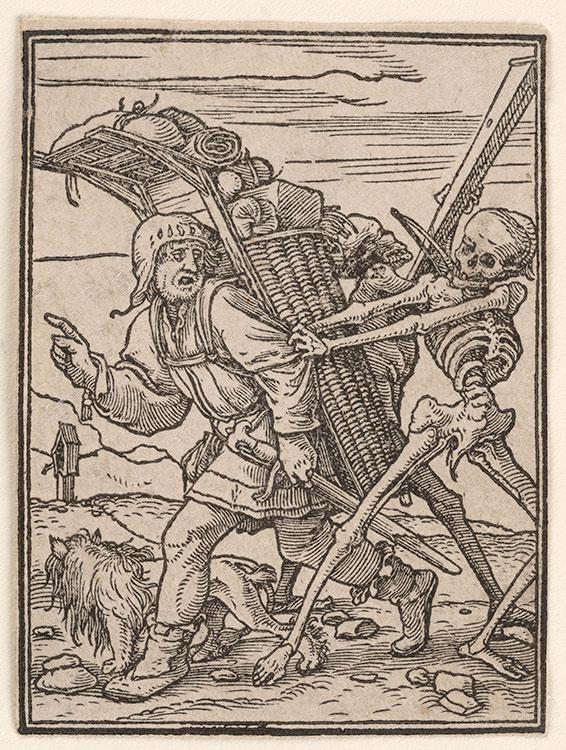

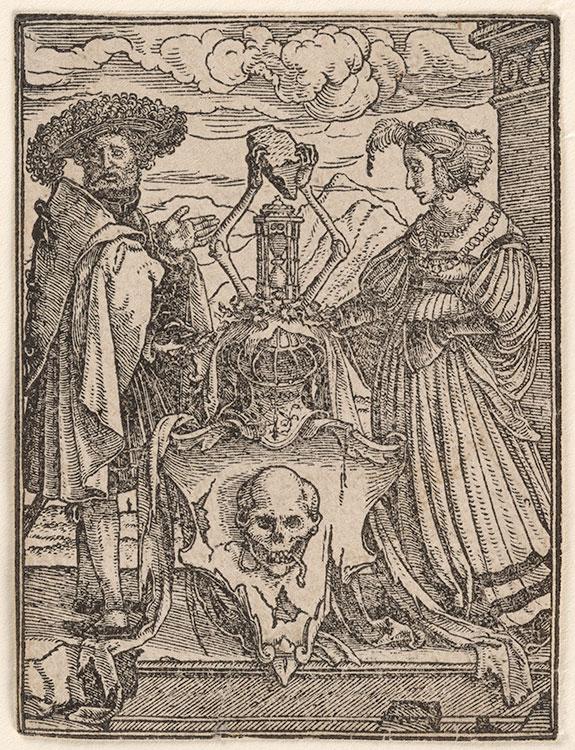

Lützelburger and Holbein reimagined the medieval dance of death into detailed genre scenes where Death catches people amid their daily routines. As in Holbein’s portraits, objects and emblems indicate individuals’ social strata or professions and in some cases mockingly aid in their demise. Lützelburger signed the bed frame in the image of the duchess (fourth frame [far right], top row, print five) with his initials, HL. Lützelburger was an exceptionally skilled blockcutter, more so than the other artists with whom Holbein had worked, and his abilities allowed for the best translation of Holbein’s compositions into print, especially at the small scale of this series.

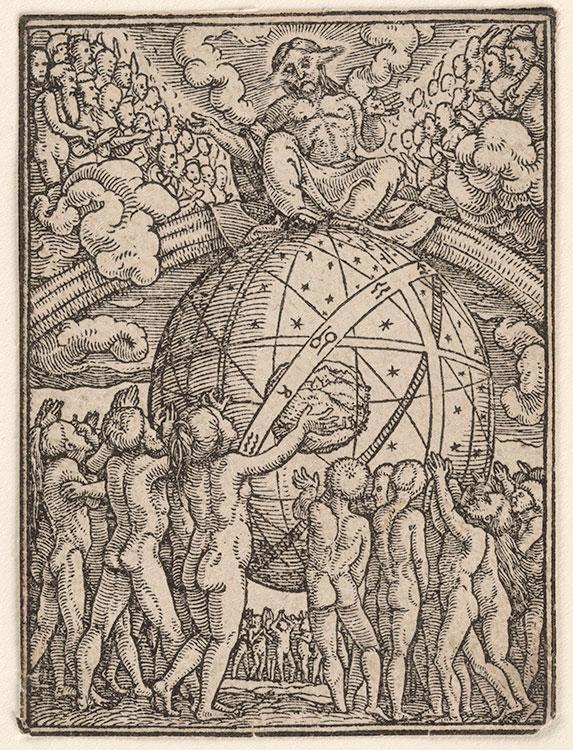

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Images of Death, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.1–40

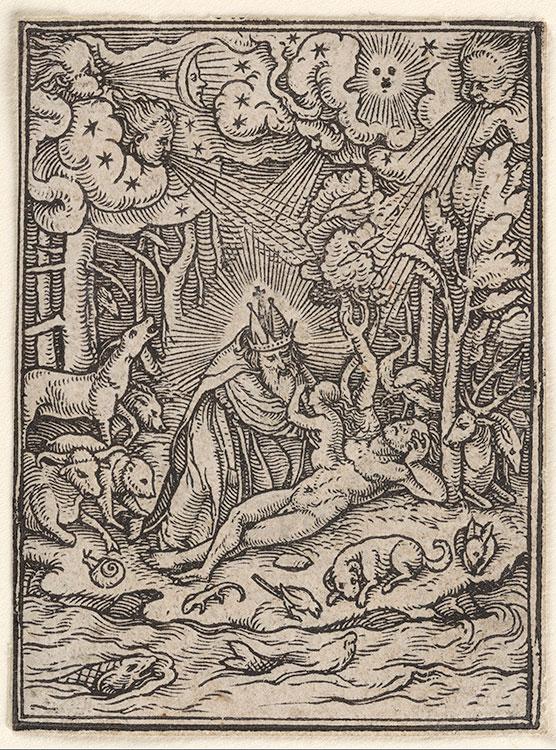

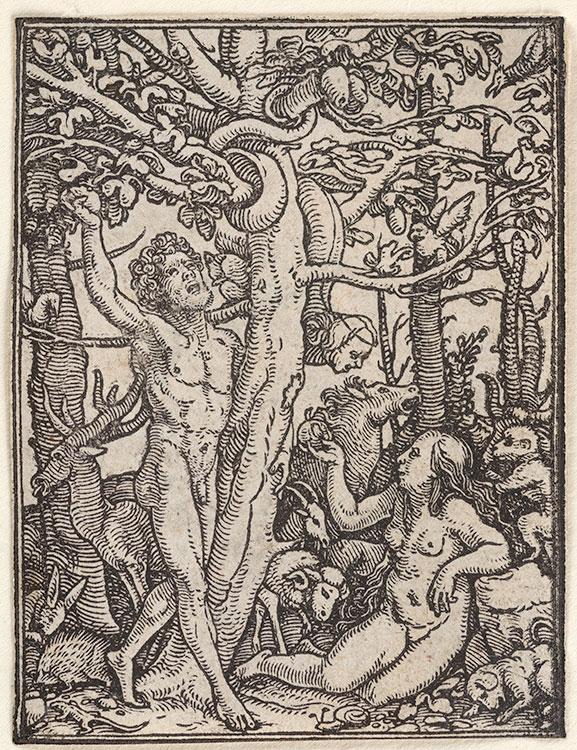

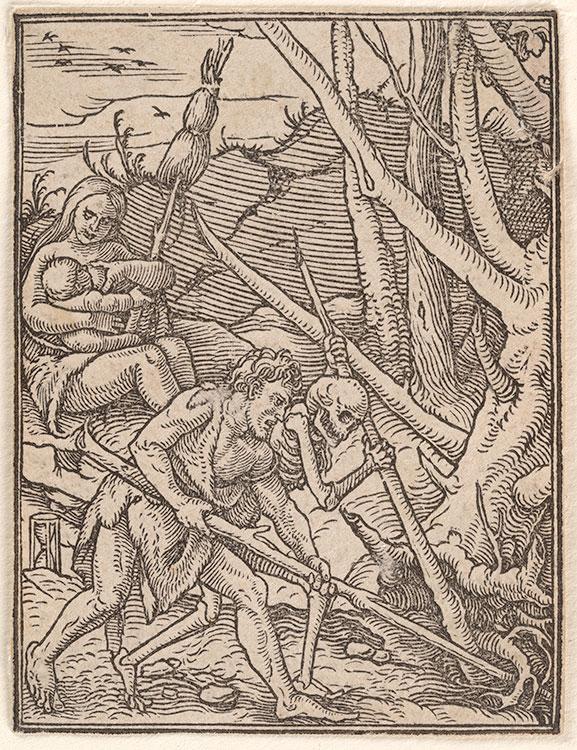

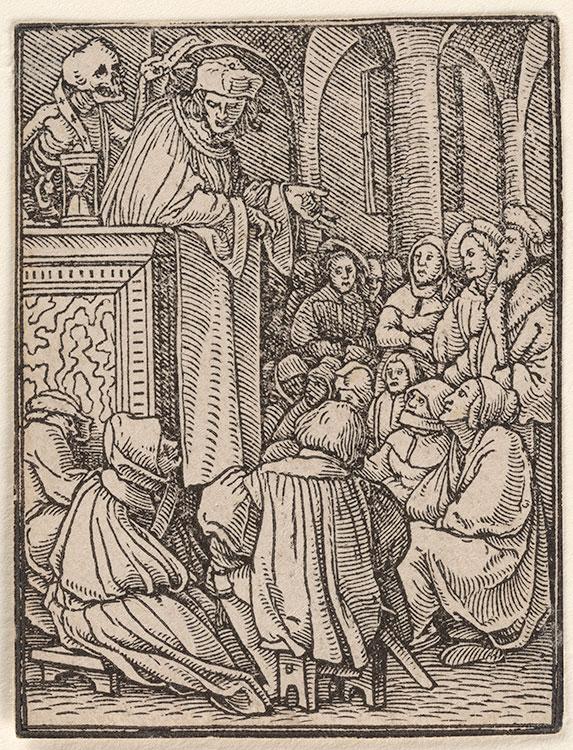

Contrary to what we might think today, during the Renaissance, the Dance of Death imagery was not considered morbid or scary. Rather, it served as a positive reminder to lead a good, devout life. While the earlier medieval tradition tended to represent the figures in the dance as rather unexpressive and static, Lützelburger and Holbein created a series full of action and high emotion, depicting the protagonists amid their daily routines.

Death comes into the story of humanity after the Fall, when Adam and Eve are banished from the Garden of Eden. These events are narrated in the first four scenes. The successive thirty-six prints represent Death meeting members of every social class. Holbein varied the compositions for each figure and adapted the manner in which they met their fate. Some protagonists, like the Monk or Rich Man, scream and try to fight off Death. The Sailor, Knight, and Count all meet rather violent ends. Death seems to surprise the Nun meeting with her lover and the Bishop tending his flock. The Old Man and Old Woman are more passive in the acceptance of their awaited fates. Some scholars have found Protestant sympathies in the scenes, as with the demons who help the Pope to sell indulgences—a practice famously criticized by Martin Luther in the Ninety-five Theses.

This series is the masterpiece of both Holbein’s and Lützelburger’s print careers. In each other, the two artists found a collaborator of equal talent to their respective expertise: Holbein finally had a blockcutter who could expertly translate his drawings into relief print, and Lützelburger had a draftsman whose mastery of three-dimensionality could be translated into print by his extraordinary deftness of carving.