Objects on view in J. Pierpont Morgan’s library reflect the past, present, and future of the collections in four curatorial departments, comprising illuminated manuscripts from the medieval and renaissance eras, five hundred years of printed books, correspondence and literary manuscripts, as well as printed music and autograph manuscripts by composers. These selections, which rotate three times a year, provide an opportunity for Morgan curators to spotlight individual items, to consider their historical and aesthetic contexts, and to tell the stories behind these artifacts and their creators. Here are some highlights of the rotation currently on view in the East Room.

YOU ARE QUEEN AND MISTRESS HERE

Illustrated by a teenage Richard “Dickie” Doyle, a Victorian artist who later regularly contributed to Punch magazine, this English translation of Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s Belle et la bête (1756) was a family affair. Doyle’s sister Adelaide translated the text, which was dedicated to their father, the Irish cartoonist John Doyle. The whimsical depictions of fairies and animals on the title page, reminiscent of medieval grotesques, contrast with the delicate drawings of Belle and the Beast throughout the tale. Confined within the Beast’s castle, here Belle holds a book that reads, “Welcome beauty banish fear / You are Queen and mistress here.” For many, the East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library evokes the quiet comfort of Belle and her books.

FIT FOR A QUEEN

The “hours” in this medieval book are not those recorded by modern timepieces but relate instead to the rhythm of eight daily prayers practiced by medieval Christians. Among them, the Hours of the Virgin were especially valued for their spiritual significance. Shown here is the beginning of Prime (around 6 a.m.), illustrated by an angel announcing the birth of Christ to shepherds. The coats of arms surrounding the miniature were likely added after 1451 to celebrate the marriage of Charlotte of Savoy and the future King Louis XI of France. The manuscript predates their union, but it was not uncommon for an older manuscript to be transformed or updated by a subsequent owner.

SEVEN WIVES

Nizami’s Quintet was one of the most celebrated compilations of poetry in the Persian-speaking world. One of the poems, Haft Paikar (The Seven Beauties), tells the story of King Bahram Gur. Its largest section is dedicated to the fifth-century king’s encounters with the titular beauties who become his wives: seven princesses from the seven regions of the world. Miniatures in this manuscript show Bahram’s encounters with each wife in her personal pavilion, each painted a different color associated with one of the planets and a day of the week. Here we see him with the Indian Princess Furak in the Black Pavilion on Saturday. Pomegranates, often associated with fertility in Iran, are depicted between them.

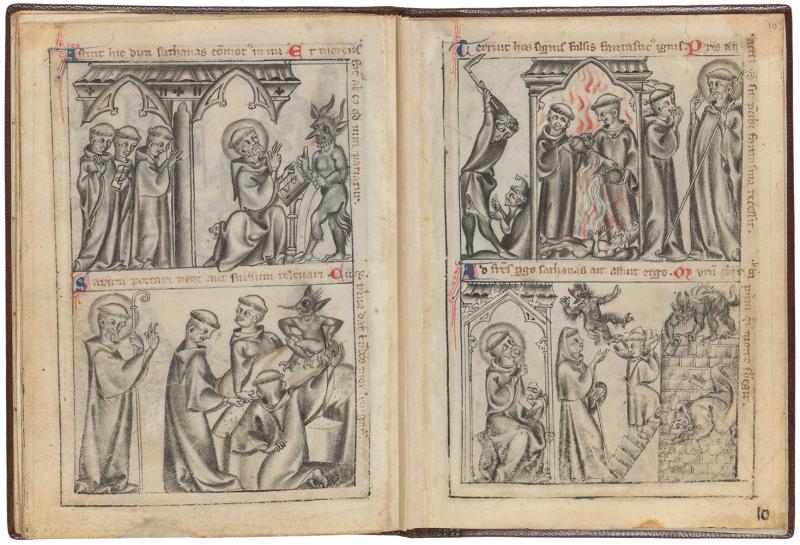

SAINTLY LIFE

This small manuscript is the earliest extant, if incomplete, copy of an account of the life of Saint Benedict (circa 480–547) that Abbot Hermann von Schuttern first composed between 1260 and 1295. The illustrations were created through the technique of grisaille, in which shades of gray are used to produce effects of light and shadow. Each opening of this volume features four scenes with captions in verse. Here, at left, a devil assails Benedict and another interferes with the monk’s work. At right, some monks fight a fire in the kitchen, and Benedict warns of approaching devils, including one who pelts the working novices with stones.

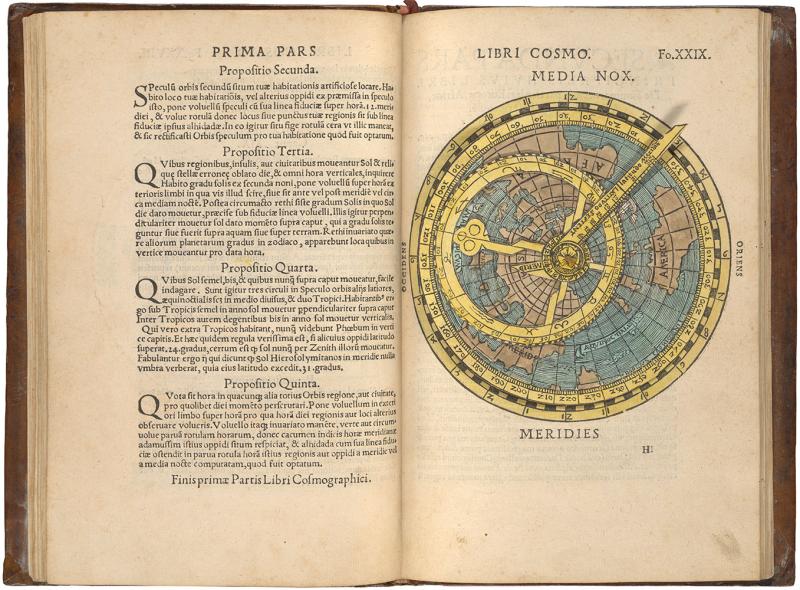

AS THE WORLD TURNS

Apian’s Cosmographia was a very popular work on navigation and astronomy. It was first published in 1524 and came out in over sixty editions. In addition to dozens of maps, diagrams, and illustrations, the book includes four volvelles, a term for rotating paper charts that were used to make mathematical or geographical calculations. The volvelle on display, titled the cosmographic mirror, enabled readers to determine the time of day (the outside ring of numbers) on different continents and the location of the sun at its zenith in any geographical location. The illustration of the continents is one of the earliest European maps to include the name America.

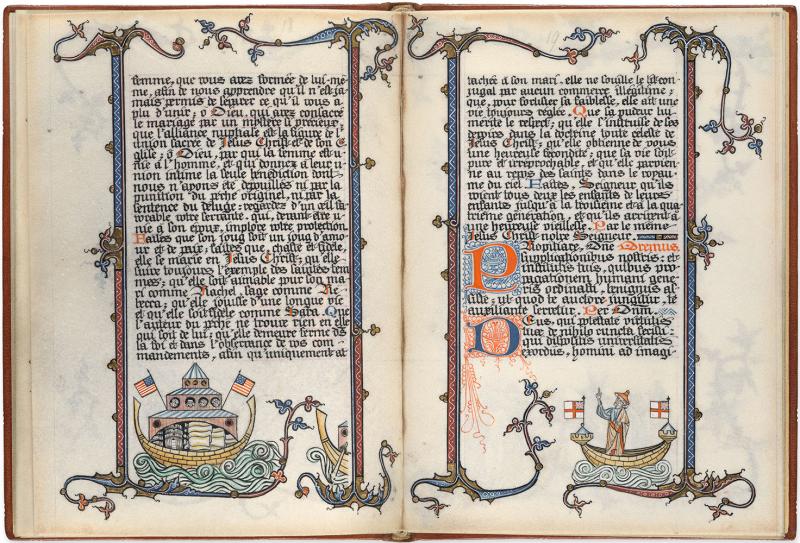

WARTIME ART

Having established a manuscript workshop in 1893, the Benedictine nuns of Maredret, Belgium, drew inspiration from medieval books. These cloistered women finished the text and the main illuminations of this manuscript not long before German troops invaded their country in August 1914. Work resumed in a clandestine manner when the nuns, exercising their creative license, began to populate the margins of the finished folios with neo-Gothic vignettes about the war. Here, at left, an American vessel brings supplies to Belgium while at right a British vessel patrols the seas.

A CONSPICUOUSLY COSTUMED CORPORAL

Dressed prints are hybrid works of paper and fabric, in which small portions of prints are cut out and replaced with textiles. To create this dressed print of a jeschenik (corporal), an anonymous craftsman altered an etching by German artist Josef Friderich Leopold, whose illustrations purported to document Turkish costumes. Portions of the figure’s hat, jacket, and underpants have been replaced with gilded red and gold textiles and a pink and blue brocade. Filtered through multiple hands, the resulting figure emphasizes the cross-cultural admiration for military fortitude while demonstrating early modern Europeans’ tendency to exoticize non-Christian peoples.

A THOUSAND WORDS WORTH A PICTURE

Textual portraits, comprised of words or letterforms arranged to resemble photographic images, are typically associated with the late twentieth century. Some anomalous precursors to this typographic artform, however, predate the postmodern examples by close to a century. In 1865 Pratt, an Iowa educator and curator, partnered with the printer August Hageboeck to produce this lithograph of the Emancipation Proclamation, which uses calligraphic text to form a portrait of Abraham Lincoln. Pratt, who would go on to teach penmanship in public schools, created other “pen portraits,” including one using the Declaration of Independence to depict George Washington, also produced as a lithograph by Hageboeck.

A FAMOUS WALTZ, A WALTZING ROSE

Weber’s memorable piece, at a stroke, placed the waltz in the Romantic piano repertory alongside the polonaise, nocturne, and scherzo. Hector Berlioz orchestrated the work to serve as a ballet in his 1841 production of Weber’s 1821 opera, Der Freischütz. Ballet lovers also know it as the music for Le Spectre de la Rose, premiered in 1911 in Paris by Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, with choreography by Michel Fokine. Diaghilev’s star dancers performed in the original production: Tamara Karsavina as the young woman who dreams that the rose she had worn to the ball comes to life as a beautiful man, and Vaslav Nijinsky as the Rose, in a pink petaled costume, who waltzes with her into the small hours of the night.

BROOKS IN BRONZE

Brooks’s mother inspired her young daughter by saying, “You are going to be the lady Paul Laurence Dunbar.” Brooks first published her poetry when she was thirteen and in 1950 became the first Black person to win the Pulitzer Prize. She used masterful and innovative techniques to portray the harmony and struggles of ordinary life, particularly Black life in Chicago. The manuscript of this poem, addressed to the sculptor of a bronze bust of Brooks, shows her edits, as well as a line that she considered throughout the poem: “You see me as unblinkingly black.” Not to her mother’s surprise, Brooks established herself within the literary canon as one of the most famous twentieth-century poets in the United States.

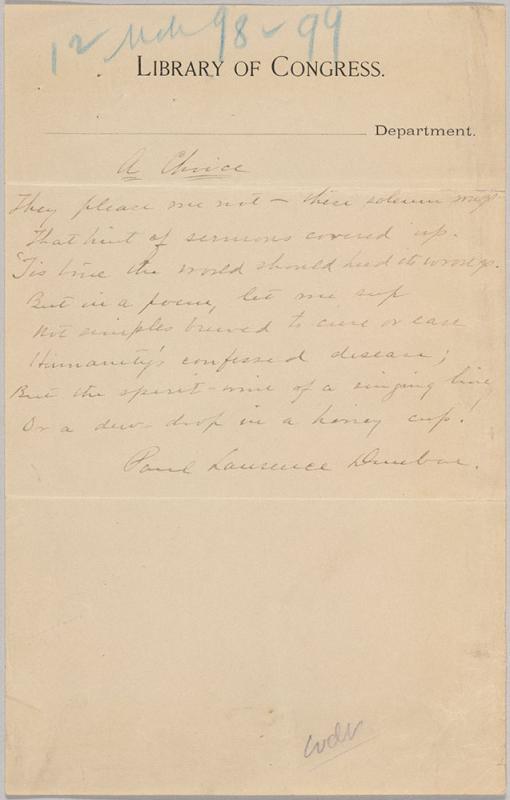

THE POET IN THE LIBRARY

Dunbar, a poet, novelist, and short story writer, composed this lighthearted stanza about poetry that shuns didacticism on the letterhead of his then-employer, the Library of Congress. He served as an assistant librarian, retrieving medical and scientific books for patrons six days a week in 1897 and 1898. He was also the first writer to give a poetry reading at the library, as part of a series of readings for the blind begun in November 1897. Dunbar was a brilliant interpreter of his own work: the audiences at the series, which soon became very popular, might have heard him read “A Choice,” along with his poem “Sympathy,” which was written around the same time. “Sympathy” includes one of his best-known lines: “I know why the caged bird sings.”

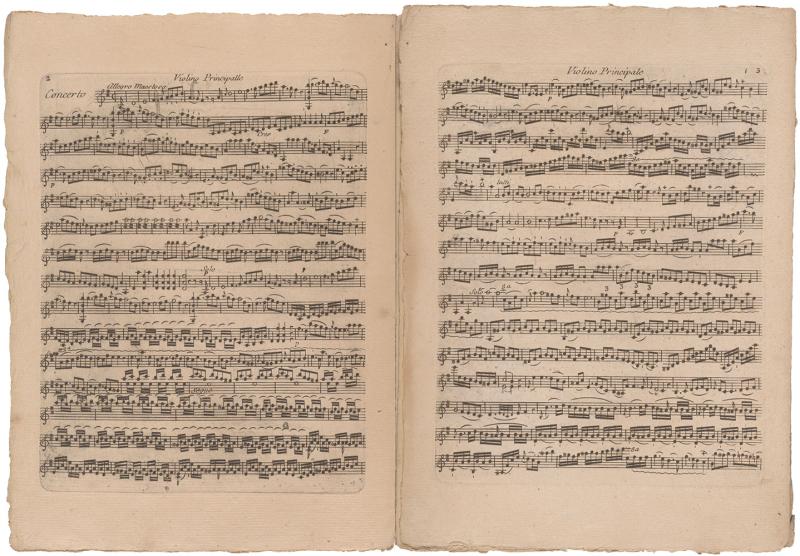

A YOUNG MAN FROM GUADELOUPE

Born in the French colony of Guadeloupe to a White plantation owner and an enslaved Creole woman, Joseph de Bologne was educated in France, where he earned the title Chevalier (knight) de Saint-Georges and lived through the tumult of the Revolution. As a conductor, violinist, prolific composer—and a skilled fencer—he is now recognized as one of the first Europeans of African descent to achieve broad acclaim in music. His life and career were retold in the 2022 film Chevalier, starring Kelvin Harrison Jr. Bologne probably composed opus 2, like many of his other violin concertos, to perform himself. The publication of his concertos, as in this score printed in 1773, attests to their popularity.

AN INDOMITABLE ADVOCATE FOR GILBERT AND SULLIVAN

After decades of neglect, Smyth’s vibrant music has begun to again receive the recognition for which she long fought. Over her father’s objections, she entered the Leipzig Conservatory, later returning to her native England to become a successful composer of operas—a genre many then considered too complex for a woman. She championed women’s right to vote and once, while imprisoned for suffragist activities in 1912, even performed her anthem March of the Women, conducting a chorus of fellow suffragettes with a toothbrush as a baton. An admirer of Gilbert and Sullivan’s late nineteenth-century operettas, Smyth advocated for light rather than grand opera. With deft humor, here she criticizes conductors’ tendency toward faster tempos, citing as an exemplar Arthur Sullivan’s composing process, which she argues was grounded in the lyrics of W. S. Gilbert.

J. Pierpont Morgan's Library