Objects on view in J. Pierpont Morgan’s library reflect the past, present, and future of the collections in four curatorial departments, comprising illuminated manuscripts from the medieval and renaissance eras, five hundred years of printed books, literary manuscripts and correspondence, as well as printed music and autograph manuscripts by composers. These selections, which rotate three times a year, provide an opportunity for Morgan curators to spotlight individual items, to consider their historical and aesthetic contexts, and to tell the stories behind these artifacts and their creators. Here are some highlights of the rotation currently on view in the East Room and the Rotunda.

A WARTIME BALLET SENSATION

“Spring 1917. The season will be short and dedicated to various works of war.” Thus the arts journal Comoedia illustré announced the latest Paris offerings of the Ballets Russes, Serge Diaghilev’s famed ballet troupe. After the company had dazzled the city with Firebird, Afternoon of a Faun, and the Rite of Spring, World War I forced them to reduce programming and perform elsewhere. They returned to Paris three years later with something fresh. Parade—with a theme by Jean Cocteau, music by Erik Satie, choreography by Léonide Massine, and stage design by Pablo Picasso (his first theater commission)—became a sensation, invoking elements from the circus, the music hall, and American movies, and inspiring one of the first published uses of the term “surrealist.”

BY HAND

Jean Cocteau worked in many media and genres, from film to poetry to visual art, and hands were one of his recurring themes throughout. Here, responding to a request for a drawing of hands, he directs his correspondent to various books in which his drawings have appeared, adding in a pun about not having examples “to hand.” But of course, the letter itself contains a drawing of a hand holding a letter—an instance of surrealistic play that recalls the photographer Philippe Halsman’s famous portrait of Cocteau as a sort of creative octopus, sporting numerous hands, each busy with a pen, paintbrush, book, or other artistic implement.

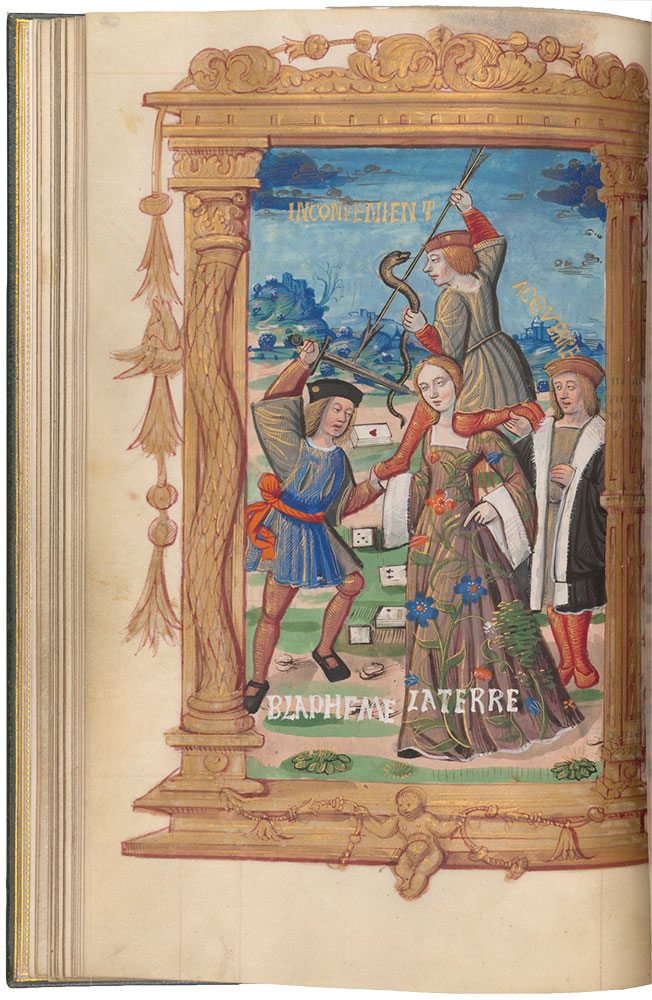

THE VICES OF THE WORLD

The Abuses of the World is a moralizing work that highlights society’s vices. While many printed versions survive, this is the only known copy written entirely by hand. In this miniature, the central female figure represents Earth. Perched on Earth’s shoulders is a personification of Hardship, who battles against Blasphemy while Greed grasps his ankle. With his left hand, Hardship restrains an attacking snake, representing Blasphemy’s venomous words. Playing cards symbolize immorality and sinfulness. The author warns that in difficult times, blasphemers curse God and the church for their lack of money, and the greedy seek to profit from tripping others by their feet. Consequently, the morally upright must take militant action against either vice.

REFLECT ON YOUR KNOWLEDGE

Charles de Bovelles, a French mathematician and philosopher, was considered by some contemporaries to be the most radical thinker of the early sixteenth century. In his influential Book on Wisdom, he tried to define the differences between medieval and Renaissance thought, illustrated in this elaborate frontispiece. For Bovelles, blind Fortune (personified on the left) dictated one’s knowledge in the Middle Ages, and the individual played no role in where they landed on Fortune’s wheel. Following humanist ideals of the Renaissance, however, Knowledge (depicted on the right, holding a mirror) required thought and reflection on the starry universe and on oneself.

A TINY MASTERPIECE

Belying its title, there are actually three central characters in Shelley’s poem: the idealist Julian, the proud and jaded Maddalo, and the Maniac, a mysterious individual who is confined to a lonely tower on the outskirts of Venice. As they travel to visit him, Julian and Maddalo debate about “God, freewill and destiny.” But the Maniac has moved beyond conversation into monologue, and when he speaks, it is of the tortured curdling of love and a lover who wishes she had “never seen me—never heard / My voice, and more than all had ne’er endured / The deep pollution of my loathed embrace.” Shelley sent this fair copy to his friend and fellow poet Leigh Hunt for forwarding to the publisher Charles Ollier and asked that it be published anonymously.

A PRAYER TO A GUARDIAN ANGEL

Books of Hours contain prayers that were intended to be recited by laypeople at set times throughout the day. The books’ decorations often juxtapose sacred images with scenes of domestic life. At left, during the Last Judgment, resurrected souls of the virtuous are ushered into heaven while the damned are carried off by demons. At right, a man kneels in prayer beneath an image of the archangel Michael. The prayer beseeches the guardian angel to watch over the man, who may represent the book’s patron. Although the manuscript was written and illuminated in Flanders (Belgium), later added text indicates it was made for a Spanish patron. The red velvet pouch was likely produced in the eighteenth century.

IN THE HEIGHTS

Sarah Flower Adams was an English poet who moved in radical Unitarian circles, contributing to publications such as the Monthly Repository and Westminster Review. In 1823 she broke the record for the quickest ascent up the mountain Ben Lomond in the Scottish Highlands by a female climber. The hymn “Nearer, My God, to Thee,” for which she wrote the lyrics, alludes to the biblical story of Jacob’s dream. Its speaker, like Jacob, wanders in the wilderness until she has a vision of “steps unto heav’n.” She imagines herself “[o]n joyful wing, cleaving the sky, / Sun, moon, and stars forgot, upwards I fly.”

IDA RUBINSTEIN BRINGS TOGETHER GIDE AND STRAVINSKY

Ida Rubinstein is little known today, yet she was a celebrity in her time. Her career launched in 1909 with Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris. She became one of the era’s most prominent and important patrons, producing and starring in stage works with Claude Debussy, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Maurice Ravel, Bronislava Nijinska, and others. In 1928 she founded a ballet company to rival Diaghilev’s, most notably commissioning and starring in Ravel’s Bolero and Stravinsky’s The Fairy’s Kiss. In 1933 she commissioned Perséphone on a poem by André Gide, based on the Homeric hymn to the Greek goddess Demeter. The collaboration was not an entirely happy one. When Stravinsky played his score for Gide, the poet was dismayed, able to say only, “It’s curious, it’s very curious . . . ”

PAINTED ON A BODHI LEAF

The Buddha achieved enlightenment beneath a tree with large, spade-shaped leaves. Revered by Buddhists, these trees became known as bodhi (or “enlightenment”) trees and were propagated throughout Asia. In China, artists used bodhi leaves to create paintings for albums like this one, thereby infusing their images with sacred power. Written in gold ink against a deep blue background, this Buddhist sutra, or scripture, describes the wonders of Sukhavati, or the Land of Bliss, an uncorrupted realm inhabited by enlightened beings. One such being is depicted here accompanied by a diminutive elephant. The brightly painted bodhi leaf was pasted into a section of cutout paper and framed with yellow silk brocade.

PROMISES, PROMISES

In this letter, the inventor of the daguerreotype teases a further innovation in the brand-new art of photography: capturing movement. “By means of that new process,” Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, writes, “it shall be possible to fix the image of objects in motion such as public ceremonies, market places covered with people, battles etc. The effect being instantaneous.” Daguerre’s caginess in his response to Hunt, an English chemist and another important early researcher into photographic processes, can be attributed to the fact that Daguerre had not actually figured out how to do what he was claiming. It was the improvements in lenses and chemicals by others in the early 1840s that eventually cut exposure times from minutes to seconds.

FIVE HUNDRED YEARS ON

In 1524 the ship La Dauphine, helmed by the Italian mariner Giovanni da Verrazzano, first entered New York harbor. Verrazzano’s report to his patron, the French king Francis I, contains the earliest European account of New York. Verrazzano described the land as “a very agreeable place between two small but prominent hills” and noted that the inhabitants were “dressed in birds’ feathers of various colors.” In the 2022 anthology Lenapehoking, a descendant of the people Verrazzano saw, Curtis Zunigha, described the Europeans’ arrival from the Lenape perspective: “They brought a world view, value system, and religion that diminished my ancestors as savages who must be dominated—and who lived on land that must be conquered, plundered.”

CARTOGRAPHIC TSENACOMOCO

“Powhatan held this state & fashion when Capt[ain] Smith was delivered to him prisoner” reads the caption at the top-left corner of this British colonial map of Virginia. A product of Smith’s three-month exploration of the Chesapeake Bay, this is one of the earliest published maps of the region known to the Algonquian-speaking people as Tsenacomoco. At once ethnographic and geographic, it depicts “Jamestowne” as an English dot awash in a sea of Indigenous American sovereignty. Signified in the coat of arms on the map’s bottom right, Smith’s life as an intrepid sailor and soldier who had traveled throughout North Africa and West Asia set the stage for the cross-cultural dynamics that would epitomize subsequent British colonial expansion.

A PENMAN’S PECULIAR HABIT

Madden’s slim guide to speaking English aimed to provide a modicum of foreign language skills for Frenchmen training to be officers at the Royal Naval Academy. This copy’s original owner, François Nicolas Bédigis, never joined the navy; instead, he became a master of calligraphy and professor at the Royal Academy of Writing. From a bibliophile’s standpoint, Bédigis’s accomplished penmanship on paper was ultimately eclipsed by the idiosyncratic designs he executed on many of the book covers in his library, such as this one. Since Bédigis never signed or dated the covers, however, some speculate they were created either by his wife, Marie-Claude Violet, or their son, Philippe, both of whom were also accomplished writing teachers.

A WILLIAM MORRIS REJECTION

Equal parts artist, poet, publisher, and graphic designer, Morris devoted the last years of his life to a sumptuous edition of the collected works of Chaucer (1342 [ ?] –1400)—the most imposing and ornate publication issued by Morris’s Kelmscott Press. His friend Edward Burne-Jones designed eighty-seven wood-engraved illustrations. Morris created a new typeface for the project and, over three years, devised around sixty varieties of decoration for its more than 550 pages, comprising titles, ornamental borders, frames, and initial letters and words. On this trial page for a border design he would ultimately reject, Morris used dummy text made up of repeating lines from Chaucer’s “Knight’s Tale.”

GOING VIRAL IN 1895

I never saw a Purple Cow, / I never hope to see one,

But I can tell you, anyhow, / I’d rather see than be one!

Burgess became famous in 1895 when he published these four lines of verse with an illustration of a cartoonish cow in the first issue of his humor magazine The Lark. Despite the periodical’s modest print run, the poem went viral. Journalists reproduced it across the country and in Europe, sometimes changing the words to suit specific situations (think memes). To capitalize on its notoriety, Burgess paired it with a poem about a giant man made of chewing gum and printed the booklets on bamboo paper.

A DANGEROUS MELODY

The Bestiary of Love is a plea from a lover to his unsympathetic lady. The text refashions the traditional animal lore of medieval bestiaries by applying the lessons of nature to the lover’s plight. At top left a weasel delivers its young through its mouth, which the author compares to a woman delivering a refusal. Below is the Caladrius, a mythical bird that could signal a sick person’s fate with its glance. If the lady looks away, the poet is doomed to suffer the death of love. At right, the author compares his lady to a siren whose sweet melody lures unsuspecting sailors to their death.

THE ART OF WRITING WELL

As Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne (ca. 742–814) led the first empire in Western Europe after the fall of Rome and sought to revitalize learning and the study of the liberal arts. He invited scholars from all over Europe to his court in an attempt to reform and standardize writing itself, which varied widely across the realm. This luxury Gospel Book from Tours provides a stunning example of the renewed interest in the art of calligraphy. At left is a title page announcing Mark’s Gospel, which begins at right. Working in gold ink, the scribe combined Roman letterforms with interlace ornaments, transforming the words into art.

THE CHILD AND THE SORCERIES

In 1919 Maurice Ravel wrote to the novelist Colette, with whom he was collaborating on a new project: “What would you think of the cup and teapot, in old black Wedgwood [porcelain], singing a ragtime?” Premiered in 1925, their resulting opera-ballet tells the moral tale of a spoiled young boy. After the boy complains to his mother about homework, he angrily abuses the objects in his home, prompting the clock, dishes, sofa, and even the garden—in combined sung and danced roles—to come to life and punish him. When he kindly tends to an injured squirrel, the household objects and his mother forgive him. Serge Diaghilev provided dancers for the production and enlisted George Balanchine, just twenty years old, to choreograph the dance sequences.

Collections Spotlight is funded in perpetuity in memory of Christopher Lightfoot Walker.