Objects on view in J. Pierpont Morgan’s library reflect the past, present, and future of building collections in four curatorial departments, comprising illuminated manuscripts from the medieval and renaissance eras, five hundred years of printed books, correspondence and literary manuscripts, as well as printed music and autograph manuscripts by composers. These selections, which rotate three times a year, provide an opportunity for Morgan curators to spotlight individual items in different ways—to consider their historical and aesthetic contexts, artistic techniques, and some of the stories behind these artifacts and their creators. Shown here are examples of the Morgan’s objects currently featured in the East Room, as well as selected items on display in the Rotunda from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

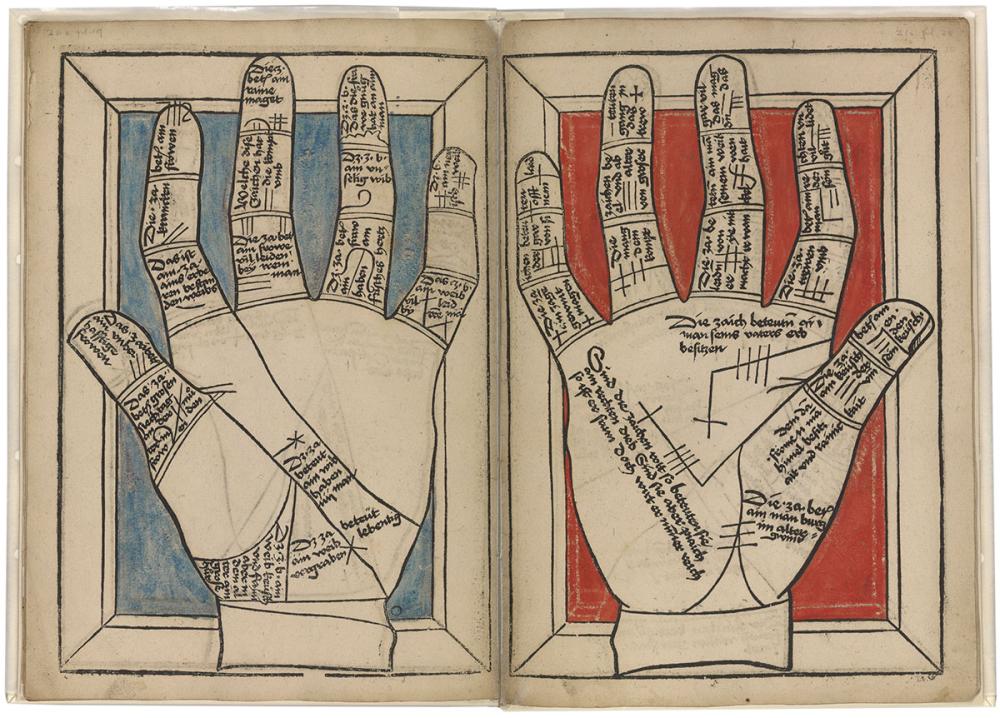

What’s My Line?

The hand represented a microcosm of the body and mind throughout the medieval and early modern eras. Students of music, religion, science, and astrology used the hand as a tool for learning and memory, and diagrams of the hand were also used in books on palmistry, or palm-reading (then known as chiromancy). This is one of four known copies of the second edition of The Art of Chiromancy, which was the first printed book on the subject. A woodcutter engraved both the images and text on woodblocks, which allowed the book to be printed quickly on demand. Hartlieb’s designs used the right hand to represent a man and the left, a woman. Despite its many misogynistic remarks, the book was dedicated to a Bavarian princess.

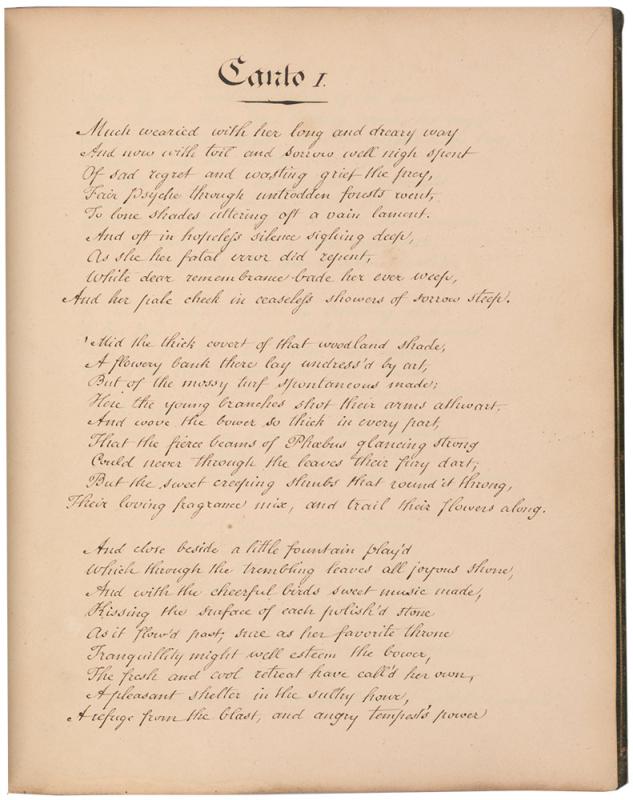

The First Epic Poem by a Woman in English

Psyche; or, the Legend of Love, by the Anglo-Irish Romantic poet Mary Tighe, was published in 1805 in an edition of fifty copies. The six-canto poem drew inspiration from Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590) and adopted its distinctive rhyme scheme (ababbcbcc), the so-called Spenserian stanza. Tighe’s poem follows the physical and spiritual journey of Psyche, a princess whose famed beauty incurs the wrath of Venus. The goddess sends her son Cupid to punish Psyche, but instead the two fall in love and marry in secret, beginning a series of quests and tribulations that ends in Psyche’s deification. Alongside the printed edition, the poem circulated in handwritten copies, such as the beautifully prepared manuscript seen here.

Amanda Gorman’s American Lyric

On view August 18, 2021 through November 21, 2021

When Amanda Gorman stepped up to the microphone at the 2021 presidential inauguration ceremony to deliver her poem “The Hill We Climb,” millions of people heard her powerful voice for the first time. But she is by no means a novice poet. In 2017, when she was nineteen, Gorman was named the first youth poet laureate of the United States by the organization Urban Word. That same year, she presented the Morgan with this manuscript of an original poem she had performed at the Library of Congress. In it, Gorman invites us to look beyond hallowed spaces (like the Morgan) to embrace a new American poetry— a living lyric embodied in everyday actions born of rage and hope.

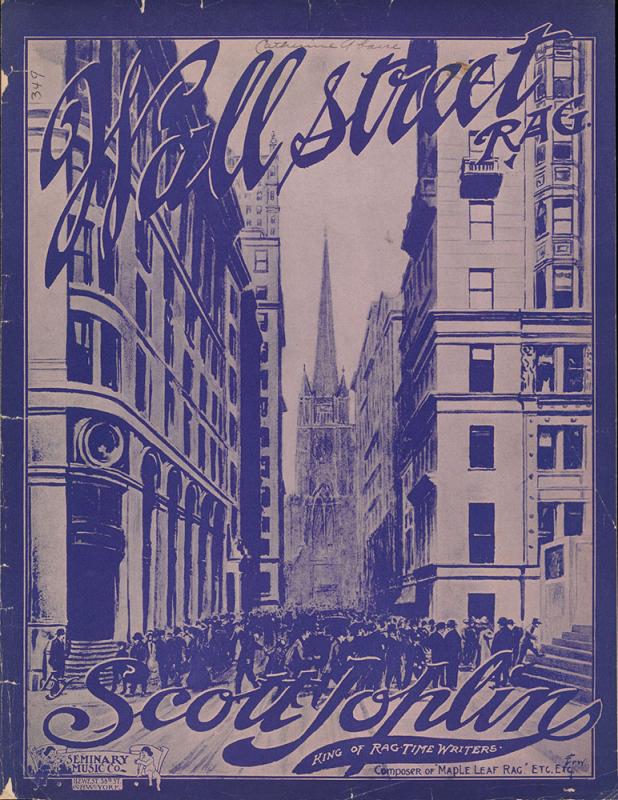

Music to Cheer Up the Stockbrokers

Called the King of Ragtime after the publication of his best-selling Maple Leaf Rag, in 1899, Joplin was promoted as America’s answer to Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849). This music depicts the Wall Street Panic of 1907 (in which the Morgan’s founder, J. Pierpont Morgan, played a key role). Joplin may have been performing at Fraunces Tavern, a historic inn near Wall Street, where he would have witnessed the distress firsthand. He labeled four musical sections: (1) Panic in Wall Street, Brokers Feeling Melancholy, (2) Good Times Coming, (3) Good Times Have Come, and (4) Listening to the Strains of Genuine Negro Ragtime, Brokers Forget Their Cares. Joplin was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 1976 for his opera Treemonisha.

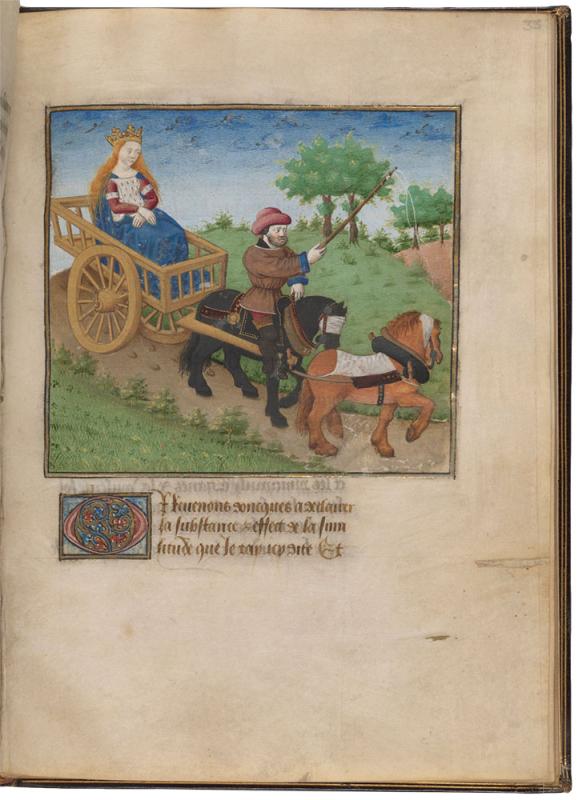

The Conflict Between Spiritual and Secular Impulses

Popular throughout the Middle Ages, allegorical texts used symbols to point to morals. Written in 1455 by Duke René of Anjou, count of Provence and king of Naples, this treatise describes the conflict between spiritual and secular impulses. In the parable illustrated here, a woman who has worked diligently to grow a crop of wheat must cross a battered bridge to bring it to the mill. Each element of the parable is significant. The woman stands for human effort, the wheat represents merit, the bridge, which groans as she treads cautiously, is equated with conscience, and the mill, powered by a waterwheel, symbolizes paradise.

Sojourner Truth’s Strategies

In her lifelong campaign against racism, Sojourner Truth used, among other strategies, personal testimony and photography—one a very old, and the other a very new form of persuasion. As soon as the technology to produce photographic cartes de visite became available and affordable in the United States, Truth embraced the medium. According to Nell Irvin Painter’s biography Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol, this image was one of Truth’s favorite photographs of herself.

A Map of the Seventh Ward

In 1896, the Seventh Ward in Philadelphia was home to 9,675 Black residents. One of them was W. E. B. Du Bois, whose study of the ward, shown here, is a landmark in American sociology. Du Bois combined questionnaires and interviews with wide-ranging archival research to produce an exceptionally detailed portrait of the area and its inhabitants. This color-coded map is just one example of the way Du Bois used data visualization techniques and other methods drawn from social science to document the effects of racism and White supremacy.

Collections Spotlight is funded in perpetuity in memory of Christopher Lightfoot Walker.