Biblia

Printed on vellum by Vindelinus de Spira in Venice, 1 August 1471

Translated into Italian by Niccolò Malermi.

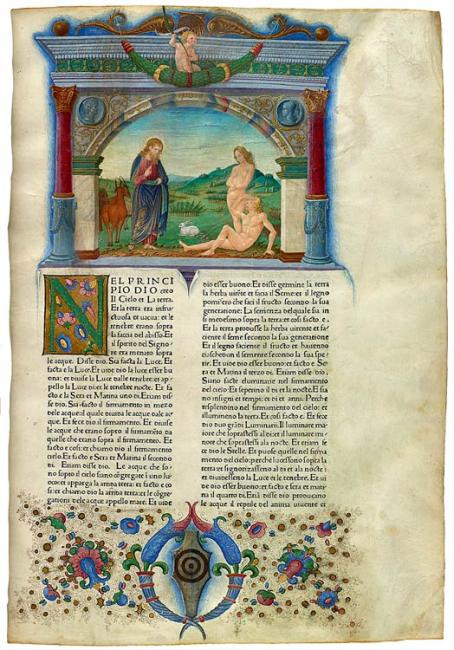

Opening, Volume 1: Creation of Eve

Purchased in 1929 PML 26983

Item description:

Professional illuminators supplied borders and initials for some of the first books printed in Venice, a center of the book trade with an affluent clientele prepared to pay handsomely for special copies decorated no less lavishly than the illuminated manuscripts of the day. An anonymous miniaturist known as the Master of the Putti produced this stunning trompe l'oeil frontispiece for the second volume of the Malermi Bible, the first edition of the Bible translated into Italian. In the framed miniature, Solomon reveals the rightful heir to an estate by having him and his heartless brothers shoot at their father's corpse, a task beyond the powers of a truly devoted son.

Most bibles were written or published in Latin. This copy, printed by Vindelinus de Spira, is in Italian. It is one of the earliest bibles published in the vernacular.

Gold highlights in The Creation of Eve, shown at the top of the page, create the impression of a sun-drenched landscape. Although the miniatures in both volumes of this bible may be attributed to the Master of the Putti, the two books originally may not have belonged together. This one may have belonged to the Cornaro family of Venice (their shield is covered by a later coat of arms), whereas the second volume displays the arms of the Macigni family.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.