St. Augustine

De civitate dei

Venice: Nicolas Jenson, 2 October 1475

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan with the library of Theodore Irwin, 1900

PML 310

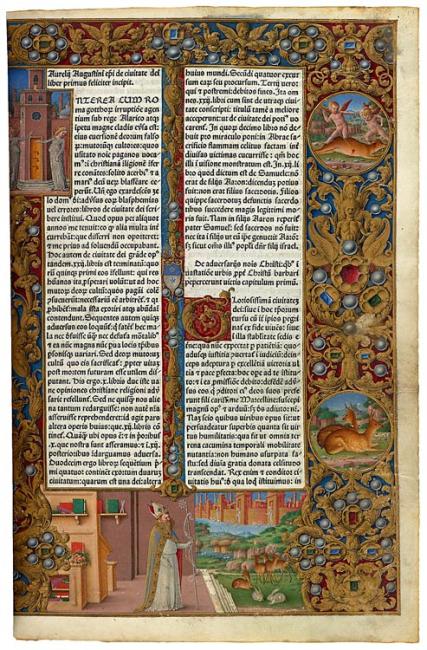

Many magnificent books were printed in Venice. This copy of De civitate Dei left the printing press without initials and decorative borders, which were added by hand—probably by Girolamo da Cremona. The lavish frontispiece depicts St. Augustine standing to the side of his scholarly study before a distant landscape. The Heavenly City of his vision, with angelic guardians standing at the gates, floats in the distance. Clearly a luxury item, this book was printed on vellum. Set unobtrusively, near the center of the page, is the blue-and-white coat of arms of the Mocenigo family. Pietro Mocenigo was doge of Venice from 1474 to 1476; the volume probably once belonged to him.

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility. The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.