NUREMBERG: DÜRER AND HUMANISM

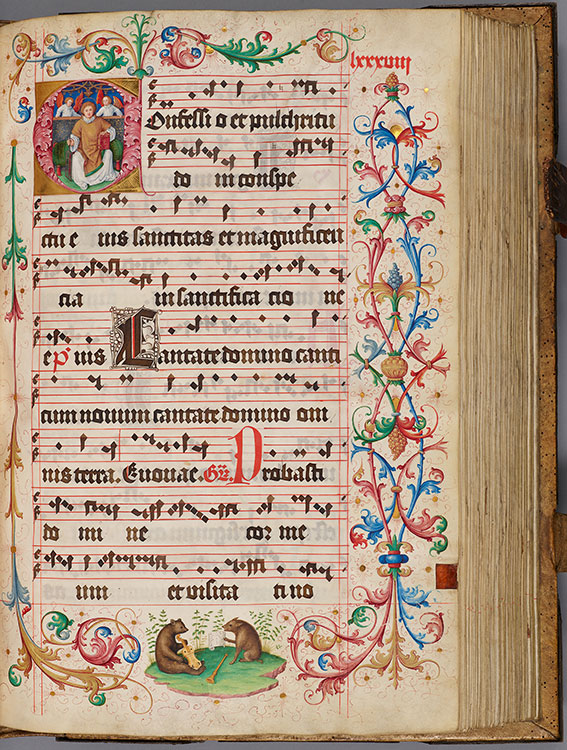

Prominent members of the parish of St. Lawrence in Nuremberg donated this massive two-volume gradual to their church. The imposing manuscript is known as the “Geese Book” after a humorous, self-referential scene of a wolf teaching a gaggle of geese to sing from a choir book on a podium, as a wily fox attacks them rom behind. Anton Kress (1478–1513), a member of the city council and relative of Willibald Pirckheimer, a humanist in Dürer’s circle, oversaw the manuscript’s production. Although working at a time when Dürer was the dominant artistic personality in Nuremberg, Jakob Elsner produced work that shows little debt to Dürer’s style. In the lower margin of the Feast of St. Lawrence, on view here, the shawm (woodwind instrument) lying on the ground may refer to the former braying of the swine who now sings the “new song” (canticum novum, mentioned in the opening words of the feast) while a bear plays a viol. The original pigskin binding, with metalwork from Nuremberg’s leading metalworker, is typical of German books of this period.

“Geese Book.” The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.905, vol. 1, fol. 186r (detail).

"Geese Book," in Latin

Illuminated by Jakob Elsner

(ca. 1460–1517)

Germany, Nuremberg, ca. 1507–10

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.905, vol. 2, fols. 87v–88r

Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, December 1962

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

Made for the church of St. Lawrence in Nuremberg in the early sixteenth century, this enormous manuscript is but one of two volumes known as the Geese Book after a whimsical, self-referential marginal image of a wolf teaching a choir of geese to sing from a choir book on a podium, while a wily fox attacks them from behind.

Other folios, such as that exhibited here, also contain satirical animal imagery. In the margin of the feast for St. Lawrence, the church’s titular saint, the shawm lying on the ground may refer to the former braying of the swine who now sings the “new song” mentioned in the accompanying chant from a sheet of music while a bear plays a viol.

A hugely ambitious project, the Geese Book was initiated by Sixtus Tucher, a member of one of the city’s leading patrician families. Tucher’s successor, Anton Kress, a member of the city’s inner council and a distant relative of the humanist Willibald Pirckheimer, Albrecht Dürer’s close friend, oversaw the bulk of its production.

The gradual was written by a vicar of the church, Friedrich Rosendorn, who is named in the volumes’ colophons. Jakob Elsner, however, the artist to whom the gradual’s decoration is attributed, goes unmentioned.

Commissions of grand manuscripts such as the Geese Book would in large part be made redundant, both by the growing predominance of printing and the spread of the Protestant Reformation, which, in keeping with the theology of Martin Luther, stressed salvation by faith alone, not by good works, which often took the form of the patronage of magnificent works of art. In this respect, the Geese Book, a product of the imperial city of Nuremberg, harks back to the grand imperial commissions of the earlier Middle Ages.