In 1819, two years before his death at age twenty-five, Keats wrote his best-known poems in an extraordinary burst of creative activity. He would complete five of his six so-called great odes in the spring of 1819—“Ode to Psyche,” “Ode to a Nightingale,” “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” “Ode on Indolence,” and “Ode on Melancholy”—and compose the sixth, “To Autumn,” that fall. Along with other celebrated poems he wrote that year, including “The Eve of St. Agnes,” “Lamia,” and “La Belle Dame Sans Merci,” the great odes would prove, in time, to secure literary immortality for Keats.

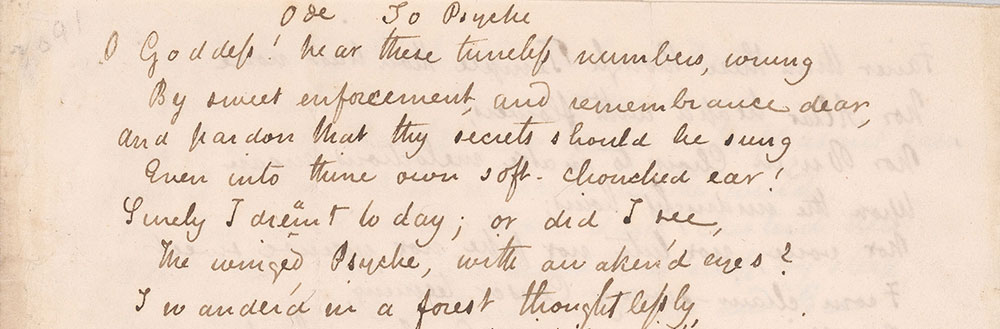

The Morgan owns the original draft of the first of these odes, completed in late April 1819. Though “Ode to Psyche” would shape the stanzaic form used in the rest of the great odes, it seems adding “Ode” to the title was somewhat of an afterthought; looking closely at the manuscript, one can see that “Ode” was written later, and slightly off to the side, of “To Psyche.” Keats recounted the composition of “Psyche” in a letter to his brother:

“it is the first and only one [i.e., poem] with which I have taken even moderate pains—I have for the most part dash’d of[f] my lines in a hurry— This I have done leisurely—I think it reads the more richly for it and will I hope encourage me to write other thing[s] in even a more peaceable and healthy spirit.”

The poem draws on the myth of Cupid and Psyche, first imagined in the second-century Metamorphoses of Apuleius and most recently (for Keats) portrayed in verse by Mary Tighe’s Psyche; or, the Legend of Love (1805). Keats knew the myth of Cupid and Psyche primarily from John Lemprière’s Bibliotheca Classica (1788), which summarizes the main elements of the story: “PSYCHE, a nymph whom Cupid married and carried into a place of bliss, where he long enjoyed her company. Venus put her to death because she had robbed the world of her son; but Jupiter, at the request of Cupid, granted immortality to Psyche.”

The speaker of “Ode to Psyche” addresses the goddess as the “latest born” of ancient deities,

Fairer than these though Temple thou hast none,

Nor Altar heap’d with flowers;

Nor Virgin Choir to make melodious moan

Upon the midnight hours.

After witnessing Cupid and Psyche “couched side by side, / In deepest grass, beneath the whispering fan / Of leaves and trembled blossoms,” the speaker resolves to devote himself to the goddess as her priest, her “pale-mouth’d Prophet dreaming”:

Yes, I will be thy Priest and build a Fane

In some untrodden Region of my mind,

Where branched thoughts, new grown with pleasant pain

Instead of Pines shall murmur in the wind.

The poem goes on to envision a temple of the imagination—“a rosy sanctuary . . . dress[ed] / With the wreathed trellis of a working brain”—built to exalt the goddess, whose name in Greek means “soul.” The striking image of the brain as a “wreathed trellis” draws its inspiration from Keats’s first career, in medicine; his 1815–16 stint as a medical student at Guy’s Hospital in Southwark exposed him to the anatomical secrets of the human body, if also traumatizing him with the potentially horrifying spectacle of pre-modern surgery.