Listen to co-curator Erica Ciallela discuss Belle Greene’s place in the history of Black librarianship.

A HARLEM LIBRARIAN

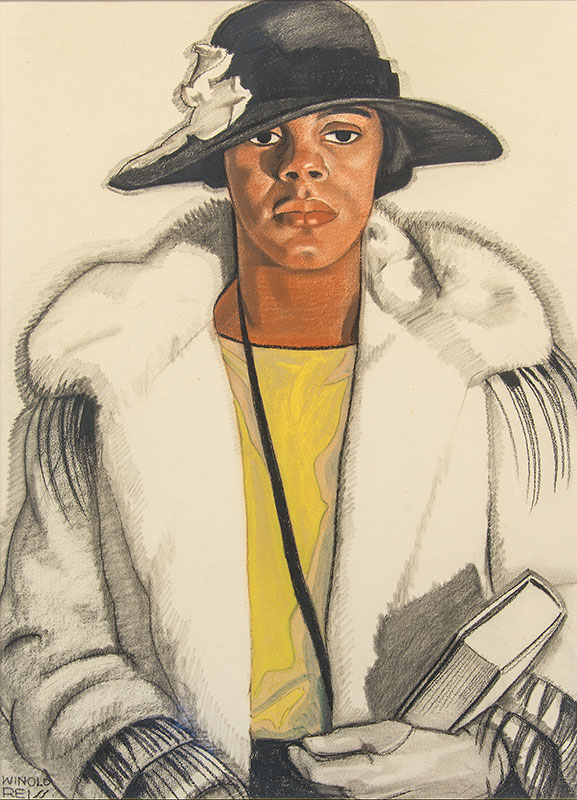

Winold Reiss made numerous portraits of Harlem residents in the 1920s, including Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Paul Robeson, Alain Locke, and other well-known cultural figures. But he also painted anonymous sitters and created composite portraits such as The Librarian. The image was reproduced as part of the series “Four Portraits of Negro Women” in the landmark March 1925 issue of Survey Graphic, titled “Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro”—an important publication of the Harlem, or “New Negro,” Renaissance. The portraits precede the educator Elise Johnson McDougald’s article “The Double Task: The Struggle of Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation.”

Winold Reiss (1886–1953)

The Librarian, 1925

Pastel and tempera on Whatman board

Fisk University Museum of Art, Nashville, Tennessee

Photography by Jerry Atnip

ERICA: Telling the story of Belle Greene’s work as a librarian demands that we turn our attention to the lives and careers of other Black librarians working in the same era. This section therefore honors Catherine Latimer, who worked at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library, now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; Regina Andrews, also of NYPL; Vivian Harsh of the Chicago Public Library; and Dorothy Porter Wesley of Howard University. These women were pioneers in their work and fought hard to bring literacy and information access to their communities. They were also inspiring speakers and writers.

Vivian Harsh once said, “If we as Negroes knew the full truth about what we, as a race, have endured and overcome just to stay alive with dignity, our respect and hunger for education would triple overnight.”

Despite making up only a small fraction of the profession, Black librarians are deeply proud of their work and outspoken in their advocacy for their communities. When Dr. Carla Hayden was appointed the Fourteenth Librarian of Congress in 2016, she brought a heightened visibility to Black librarians on a national stage. As she once said, “Now we are fighters for freedom, and we cause trouble! We are not sitting quietly anymore.”

Belle da Costa Greene was a Black librarian, even if she did not identify as such. Her work as a librarian did not impact Black communities in the same way as did the practices of her contemporaries, such as Catherine Latimer at NYPL. This is not to diminish Greene’s accomplishments in any way, but rather to uplift the work of other Black librarians at the time who have not been as prominently discussed as Greene.