The first author known by name in history was a woman: Enheduanna. She received this name, which means “high priestess, ornament of heaven” in Sumerian, upon her appointment to the temple of the moon god in Ur, a city in southern Mesopotamia, in present-day Iraq. As the daughter of the Akkadian king Sargon (ca. 2334–2279 BC), Enheduanna not only exercised considerable religious, political, and economic influence but also left an indelible mark on world literature by composing extraordinary works in Sumerian. Her poetry reflected her deep devotion to the goddess of sexual love and warfare—Inanna in Sumerian, Ishtar in Akkadian.

Making Enheduanna its focal point, this exhibition, co-curated by Sidney Babcock and Erhan Tamur, brings together a comprehensive selection of artworks that capture rich and shifting expressions of women’s lives in Mesopotamia during the late fourth and third millennia BC. These works bear testament to women’s roles in religious contexts as goddesses, priestesses, and worshippers, as well as in social, economic, and political spheres as mothers, workers, and rulers.

Women Emerge

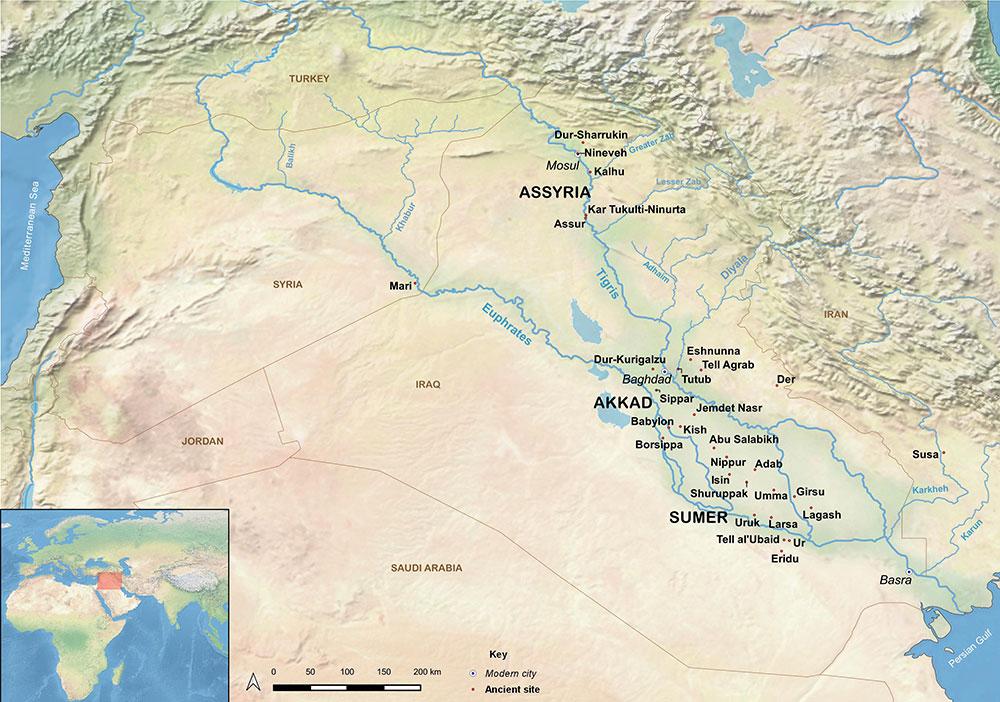

The exhibition opens with an overview of representations of women from the earliest Mesopotamian cities founded around 3500 BC, where writing was invented and major cult centers were formed. The rise of urban life in these early complex societies highly depended on women’s labor. As skilled workers, they produced textiles, pottery, and various agricultural goods (Figure 1).

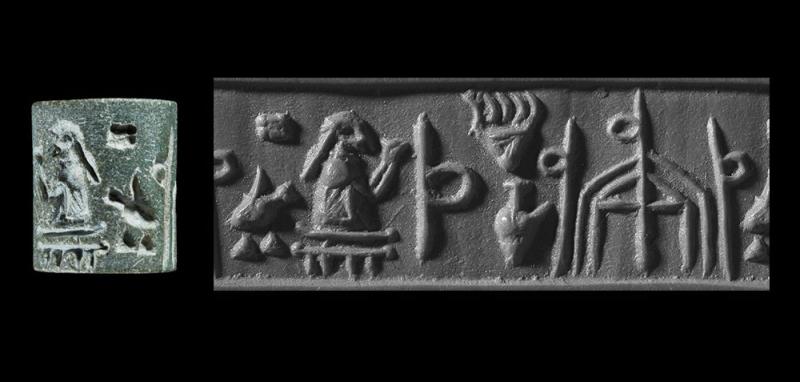

Women were also active participants in the realm of religion. Hundreds of Mesopotamian deities, arranged in genealogical hierarchies, were known by name, and each presided over specific aspects of human life. Individuals, communities, cities, and states honored particular patron deities, for whom they constructed special places of worship and carried out elaborate rituals. Women engaged in these religious practices both as priestesses overseeing the cult and the organization of temples and as worshippers bringing offerings to the temples and dedicating images of themselves praying to deities. (Figures 2, 3).

Figure 3: Cylinder seal (and modern impression) with two female figures presenting offerings, Early Dynastic IIIa period, ca. 2500 BC, marble, 1 11/16 × 1 in. (4.3 × 2.5 cm); Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, acquired from Elias Solomon David, 1912; VA 03878. Photo: SMB/Olaf M. Teßmer.

Realm of Inanna

To fully appreciate the role of women in ancient Mesopotamia, one must also look to their divine counterparts, goddesses. The fourth millennium BC marks the earliest symbolic representations of deities. For instance, reed-ring bundles, which served as doorposts in the marshes of southern Mesopotamia, resembled the cuneiform rendering of Inanna’s name and became a visual symbol for her presence (Figure 4). As a warlike goddess, she was fierce and unforgiving, but she supported her favorite kings in battle and legitimized their political power. In fact, the concord between her and the ruler was central to the sustenance of the people, the maintenance of the herds, and the well-being of the land (Figure 5). Simply put, her presence preserved the cycle of life in early Mesopotamia, so clearly displayed in the celebrated Uruk Vase (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Cylinder seal (and modern impression) with “priest-king” and rams, Late Uruk–Jemdet Nasr period, ca. 3300–2900 BC, marble and bronze, with handle: 3 1/8 × 1 3/4 in. (8 × 4.5 cm), without handle: 2 1/8 × 1 3/4 in. (5.4 × 4.5 cm); Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, acquired by Conrad Preußer, 1915, near Uruk; VA 10537. Photo: SMB/Olaf M. Teßmer.

Figure 6: Uruk Vase, Uruk (modern Warka), Eanna Precinct, Late Uruk–Jemdet Nasr period, ca. 3300–2900 BC, The Iraq Museum, Baghdad, excavated 1933–34; IM 19606. A plaster cast of the vase, loaned from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, will be on view. Photo: Wikimedia, CC-BY-SA-4.0.

Goddesses Visualized

In the centuries to come, deities began to be represented anthropomorphically, and iconographical conventions were developed to differentiate goddesses and mortal women. Goddesses were shown wearing horned crowns over their voluminous hair, for example, or holding clusters of dates. At times, the crowns are arrayed with branches, feathers, or animal heads; vegetal elements, such as flowers or stems, are occasionally seen above their shoulders– symbolizing fertility and abundance. In addition, particular goddesses began to be represented frontally, with direct gazes that exuded power and authority (Figures 7, 8).

Fig 7: Fragment of a vessel with frontal image of goddess, Early Dynastic IIIb period, ca. 2400 BC, basalt, 9 7/8 × 7 5/16 × 1 9/16 in. (25.1 × 18.6 × 4 cm); cuneiform inscription in Sumerian; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, acquired 1914–15; VA 07248. Photo: SMB/Olaf M. Teßmer.

Fig 8: Wall plaque with priest before the goddess Ninhursag, Girsu (modern Tello), Early Dynastic IIIa period, ca. 2500 BC, calcite, 6 7/8 × 6 5/16 × 13/16 in. (17.4 × 16 × 2.1 cm); Musée du Louvre, Départment des Antiquités Orientales, Paris, excavated 1881; AO 276. Photo: Musée du Louvre/Ali Meyer.

Individual Women & Women of Prominence

Mortal women likewise featured a rich repertoire of hairstyles, garments, and accessories as reflected in their votive portraits. Portraiture in ancient Mesopotamia was more concerned with capturing an individual’s essence than her likeness, and these portraits stood for the depicted individuals in sanctuaries, in proximity to the divine for perpetuity (Figure 9). Many of these women took part in economic transactions, oversaw festive banquets, and participated in religious rituals. For instance, a pair of objects shaped like crafting tools record the first woman in history known by name, KA-GÍR-gal, who may have been involved in a land sale (Figure 10). Another remarkable work, bearing the earliest known artist’s signature, records the donation of an estate on behalf of a woman named Shara-igizi-Abzu (Figure 11).

Figure 9: Standing female figure with clasped hands, Tutub (modern Khafajah), Nintu Temple VII, Early Dynastic IIIb period, ca. 2400 BC, gypsum, 16 9/16 × 5 11/16 × 4 5/16 in. (42 × 14.5 × 11 cm); The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, excavated 1932/33; A11441. Photo: The University of Chicago.

Figure 10: Stone scraper and chisel recording the first woman known by name, Jemdet Nasr–Early Dynastic period, ca. 3000–2750 BC, schist (phyllite), 3 × 6 5/16 in. (7.6 × 16 cm), chisel: 7 1/16 × 1 5/8 in. (17.9 × 4.1 cm); Proto-cuneiform inscriptions; The British Museum, London, acquired from Dr. A. Blau, 1899; BM 86260 and 86261. Photo: Joan Aruz (ed.), Art of the First Cities (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003), p. 39.

The first half of the exhibition ends with one of the most famous personalities from ancient Mesopotamia: Queen Puabi of Ur (ca. 2500 BC). She died at about age forty and was interred in a stone tomb chamber with an elaborate ceremony, which involved the ritual sacrifice of soldiers, musicians, and servants. Her body, when excavated in 1927, was still adorned with beads of precious stones and other pieces of jewelry, as well as an ornate headdress that represents the earliest perfection of metalworking techniques that are still in use today (Figure 12). In addition, three cylinder seals were found against her upper right arm, attached to three garment pins that secured her cloak (Firgure 13). Although women’s seals generally bore inscriptions describing them in relation to their husbands and fathers, Puabi’s seal only gives her own name and title as queen, which suggests that she ruled in her own right.

Figure 11: Stele of Shara-igizi-Abzu, possibly Umma (modern Tell Jokha), Early Dynastic I–II period, ca. 2900–2600 BC, gypsum alabaster, 8 7/8 × 5 3/4 × 3 3/4 in. (22.4 × 14.7 × 9.5 cm); Cuneiform inscription; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Funds from various donors, 1958; 58.29. Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 12: Queen Puabi’s funerary ensemble, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), PG 800, Puabi’s Tomb Chamber, on Puabi’s body, Early Dynastic IIIa period, ca. 2500 BC, Gold, lapis lazuli, carnelian, silver, and agate; University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, USA, excavated 1927/28. Photo: University of Pennsylvania/Bruce White.

Enheduanna: High Priestess, First Author

The second half of the show centers around Enheduanna, her literary works, related images, and her abiding legacy. By the late twenty-fourth century BC, the Akkadian king Sargon (ca. 2334–2279 BC) had united the majority of Mesopotamia under his authority and paved the way for the world’s first empire, the Akkadian Empire. Its capital, Agade, possibly located close to modern-day Baghdad, has yet to be discovered. Sargon’s appointment of his daughter Enheduanna as the high priestess of the moon god Nanna in Ur was part of his efforts to consolidate his new empire. In Enheduanna’s writings, all written in Sumerian despite her Akkadian origins, the Sumerian goddess Inanna was merged with her Akkadian counterpart, Ishtar. Whereas much of ancient Mesopotamian literature is unattributed, Enheduanna introduced herself by name in two of her poems, “The Exaltation of Inanna” and “A Hymn to Inanna.” A third one, “Inanna and Ebih,” is ascribed to her due to its style and content. All of these texts come down to us only in copies made centuries after her death (Figure 14).

Figure 13: Cylinder seal (and modern impression) of Queen Puabi, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), PG 800, Puabi’s Tomb Chamber, against Puabi’s upper right arm, Early Dynastic IIIa period, ca. 2500 BC, lapis lazuli, 1 15/16 × 1 in. (4.9 × 2.6 cm); Cuneiform inscription in Sumerian: Queen Pu-abi; The British Museum, London, excavated 1927/28; BM 121544. Photo: The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 14: Tablets inscribed with “The Exaltation of Inanna” in three parts, possibly Larsa (modern Tell Senkereh), Old Babylonian period, ca. 1750 BC, clay, each 3 13/16 × 2 5/16 × 1 1/4 in. (9.7 × 5.9 × 3.1 cm); Yale Babylonian Collection, purchase; YPM BC 018721/YBC 4656 (lines 1–52), YPM BC 021234/YBC 7169 (lines 52–102), YPM BC 021231/YBC 7167 (lines 102–53). Photo: YBC/Klaus Wagensonner.

In “The Exaltation of Inanna,” Enheduanna included astonishing autobiographical details such as her struggle against a certain Lugalanne, most likely the historically attested king of Ur, who attempted to forcefully remove her from her office:

Yes, I took up my place in the sanctuary dwelling,

I was high priestess, I, Enheduanna.

Though I bore the offering basket, though I chanted the hymns,

A death offering was ready, was I no longer living?

I went towards light, it felt scorching to me,

I went towards shade, it shrouded me in swirling dust.

A slobbered hand was laid across my honeyed mouth,

What was fairest in my nature was turned to dirt.

O Moon-god Suen, is this Lugalanne my destiny?

Tell heaven to set me free of it!

Just say it to heaven! Heaven will set me free!

[…]When Lugalanne stood paramount, he expelled me from the temple,

He made me fly out the window like a swallow, I had had my taste of life,

He made me walk a land of thorns.

He took away the noble diadem of my holy office,

He gave me a dagger: ‘This is just right for you,’ he said. 1

Enheduanna turned to Inanna for help, as the moon god Nanna, whom she served, remained indifferent to her pleas. Fortunately, Inanna accepted her prayers, and Enheduanna was restored to her office:

The almighty queen, who presides over the priestly congregation,

She accepted her prayer.

Inanna’s sublime will was for her restoration.

It was a sweet moment for her [Inanna], she was arrayed in her finest, she was beautiful beyond compare,

She was lovely as a moonbeam streaming down.

Nanna stepped forward to admire her.

Her divine mother, Ningal, joined him with her blessing,

The very doorway gave its greeting too.

What she commanded for her consecrated woman prevailed.

To you, who can destroy countries, whose cosmic powers are bestowed by Heaven.

To my queen arrayed in beauty, to Inanna be praise! 2

This poem was the culmination of her struggle, a cry that she no longer could keep inside. In fact, she added a remarkable line about her own creative process, stating that she has “given birth” to this poem:

One has heaped up the coals (in the censer), prepared the lustration.

The nuptial chamber awaits you, let your heart be appeased!

With ‘it is enough for me, it is too much for me!’ I have given birth, oh exalted lady, (to this song) for you.

That which I recited to you at (mid)night

May the singer repeat it to you at noon! 3

Enheduanna also compiled short temple hymns that praised various Mesopotamian sanctuaries. There she articulated a unified religious landscape by connecting the temples of southern Mesopotamia with those in the north, perhaps in line with the broader political aspirations of her father. The postscript to the last hymn attributes its compilation to Enheduanna:

The compiler of this tablet is Enheduanna.

My king, something has been produced that no person had produced before. 4

Figure 15: Disk of Enheduanna, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), gipar, Akkadian period, ca. 2300 BC, alabaster, 10 1/16 × 2 3/4 in. (25.6 × 7 cm); Cuneiform inscription in Sumerian: En-ḫ[e]du-ana, zirru priestess, wife of the god Nanna, daughter of Sargon, [king] of the world, in [the temple of the goddess Inan]na-ZA.ZA in [U]r, made a [soc]le (and) named it: ‘dais, table of (the god) An’; University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, USA, excavated 1926; B16665. Photo: University of Pennsylvania.

Figure 16: Fragments of a cylinder seal (and modern impression) naming Enheduanna and her coiffeur, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), PG 503, Akkadian period, ca. 2300 BC, lapis lazuli, 1 3/8 × 7/8 in. (3.5 × 2.25 cm), Cuneiform inscription in Sumerian: En-ḫedu-ana, daughter of Sargon: Ilum-pāl[il] (is) her coiffeur; The British Museum, London, excavated 1927–28; BM 120572. Photo: Trustees of the British Museum.

In addition to these extraordinary literary compositions, a number of artworks referencing her name or image come down to us. On a notable disk-shaped alabaster plaque, dedicated to a temple in commemoration of a construction, her powerful gaze meets ours (Figure 15). A clay sealing and two seals belong to individuals in Enheduanna’s entourage, identify her by name, and testify to her eminent position overseeing many institutions (Figure 16). These seals feature “contest scenes,” a popular theme in Mesopotamian glyptic, showing battling animals, heroes, and hybrid beings. Their struggle is interpreted as one between the wild and the domesticated, the chaotic and the orderly. Although Akkadian-period seals generally isolate the contesting pairs, as exemplified by the spectacular banded chalcedony seal of Shaggullum (Figure 17), seals owned by Enheduanna’s servants retain the friezelike, continuous compositions of earlier periods. This visual continuity with the Sumerian past accords with Enheduanna’s role in her father’s ambition to unify Sumer and Akkad.

Figure 17: Cylinder seal (and modern impression) with contest scene, Akkadian period, ca. 2200 BC, banded chalcedony, 1 7/16 × 15/16 in. (3.6 × 2.3 cm); Cuneiform inscription in Sumerian: Puzur-Šullat, šangû priest of BÀD.KI, Šaggullum, the scribe, (is) his servant; The British Museum, London, acquired 1825, ex-collection Claudius James Rich; BM 89147. Photo: Trustees of the British Museum.

Empire of Ishtar

Enheduanna’s writings were also essential for the aforementioned fusion between Inanna and Ishtar and the latter’s eventual eclipsing of the former. Ishtar became the foundation of the Akkadian Empire, which is referred to as the “dynasty of Ishtar” in later historical sources. An inscription from the time of the king Naram-Sin, Enheduanna’s nephew and Sargon’s grandson, states that it is through Ishtar’s love that Naram-Sin rules the land. Moreover, Enheduanna’s temple hymns culminate with Ishtar’s temple at Agade, indicating its primacy, and in “The Exaltation of Inanna,” it is Ishtar who helps the high priestess restore order. Enheduanna’s characterization of the goddess—her propensity for violence, associations with fertility, and superiority within the Mesopotamian pantheon—may even have influenced contemporary visual portrayals. In scenes carved on cylinder seals from the Akkadian period, Ishtar is often shown dominating formidable lions and gods while turning toward the viewer. Maces and sickle axes are seen around her shoulders as well as branches bearing fruit (Figure 18). Such images and Enheduanna’s texts worked together to form a powerful and threatening representation of the goddess.

Figure 18: Cylinder seal (and modern impression) with goddesses Ninishkun and Ishtar, Akkadian period (ca. 2334–2154 BC), limestone, 1 5/8 × 1 in. (4.2 × 2.5 cm); Cuneiform inscription: To the deity Niniškun, Ilaknuid, [seal]-cutter, presented (this); The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, acquired 1947; A27903. Photo: The University of Chicago.

Motherhood: Birth, Creation, and Nurturing

As mentioned earlier, Enheduanna described herself as a mother to her poem “The Exaltation of Inanna.” The concept of motherhood in her day extended beyond biology to recognize the nurturing provided by wet nurses, midwives, and mothers both human and divine. According to ancient texts, the quintessential Mesopotamian mother goddess, Ninhursag, embodied these various types of motherhood by giving form to kings’ bodies, assisting in their births, and serving as their wet nurse. King Eannatum of Lagash (ca. 2450 BC) claimed to have been nourished with Ninhursag’s holy milk, and he felt honored by the long-lasting bond formed between him and his divine wet nurse. Glyptic imagery from both Sumer and Akkad attests to the many maternal figures that could exist in a child’s life, often demonstrating the pride these figures took in the nurturing they provided (Figure 19).

Figure 19: Cylinder seal (and modern impression) with mother and child attended by women, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), PG 871, Akkadian period (ca. 2334–2154 BC), carnelian and gold, 3/4 × 3/8 in. (1.9 × 1 cm); University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, USA, excavated 1928; B16924. Photo: University of Pennsylvania.

Women Who Came After

The office of the high priestess not only existed prior to Enheduanna’s time, as reflected in a wall plaque featuring a frontally-depicted high priestess overseeing a libation ritual, (Figure 20) but also remained intact for centuries to come. Many later high priestesses were, like Enheduanna, daughters of rulers and heads of major temples, wielding religious, political, and economic power. They are generally distinguished by their flounced robes, long and loose hairstyles, and characteristic headdresses. Such iconographic features help us identify other figures as high priestesses, such as a female head with deeply cut, piercing eyes found in the sacred precinct at Ur, (Figure 21) or an exquisite statuette with a tablet in her lap encapsulating one of the main threads of the exhibition: women and authorship (Figure 22). Other women of high rank, including members of the royal family, were often depicted wearing fringed garments and having their hair tied in chignons or other intricate coiffures (Figure 23). The exhibition concludes with a selection of such images from the end of the third millennium BC.

Figure 21: Head of a high priestess (?) with inlaid eyes, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), area EH, south of gipar, Akkadian period (ca. 2334–2154 BC), alabaster, shell, lapis lazuli, and bitumen, 3 3/4 × 3 1/8 × 3 3/8 in. (9.5 × 8 × 8.5 cm); University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, USA, excavated 1926; B16228. Photo: University of Pennsylvania.

Figure 23: Fragment of a standing female figure with clasped hands, Girsu (modern Tello), possibly the reign of Gudea, ruler of Lagash, ca. 2150 BC, chlorite, 7 × 4 5/16 × 2 5/8 in. (17.8 × 11 × 6.7 cm); Musée du Louvre, Départment des Antiquités Orientales, Paris, excavated 1881; AO 295. Photo: R.M.N./H. Lewandowski.

The artworks that are brought together in She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia showcase painstaking artistry and striking stylistic variety in the representation of women, often combining delicately executed naturalism with powerfully expressive stylization. These works have withstood millennia, lending us breathtaking insight into an often-overlooked aspect of an ancient patriarchal society: womanhood. In particular, Enheduanna’s passionate voice had a lasting impact as her writings continued to be copied in scribal schools for centuries after she died. Uniting a spectacular assortment of her texts and related images for the first time, She Who Wrote celebrates Enheduanna’s timeless poetry and abiding legacy as an author, a priestess, and a woman.

She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia is made possible through the generosity of Jeannette and Jonathan Rosen. Additional support is provided by Becky and Tom Fruin, Laurie and David Ying, and by a gift in memory of Max Elghanayan, with assistance from Lauren Belfer and Michael Marissen, and from an anonymous donor.

Department of Ancient Western Asian Seals and Tablets

The Morgan Library & Museum

Footnotes

- Benjamin R. Foster, The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 333-34.

- Benjamin R. Foster, The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 336.

- William W. Hallo and J. J. A. van Dijk, The Exaltation of Inanna (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1968), 33.

- Charles Halton and Saana Svärd, Women’s Writing of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Anthology of the Earliest Female Authors (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 79.