Amidst the soft ambiance of the North Room, formerly Belle da Costa Greene’s office, the ancient western Asian cylinder seals stand as witnesses to history. Each seal is a window into the past, revealing the sophisticated artistry and profound symbolism cherished by the people of Mesopotamia, the land between two rivers. As you gaze upon these artifacts, you can't help but marvel at the skill and dedication of the artisans who crafted them, transforming simple stones into enduring legacies of their cultures. These small cylindrical stone objects were carved with intricate designs by craftspeople thousands of years ago. Their delicate work has survived the ages to give us insight into the cultural, political, and religious ideas of ancient Mesopotamia. The seals, made from precious stones, were used as a kind of signature, meant to leave impressions on clay documents and goods. The owner of a seal would roll it over clay sealings or tablets to leave their distinctive impression on an object. They were also worn as protective amulets and as symbols of status. Archaeologists rarely find a seal and its original impression together, so museum curators today will make a modern clay impression to display with the seal. This way, the scenes carved on them can be clearly seen, as in the North Room.

I am the academic year intern in the Department of Ancient Western Asian Seals and Tablets. As part of my internship I have had the opportunity to closely look at the imagery carved onto the Morgan’s seals. I’m currently a graduate student at New York University, studying religion and astronomy in ancient Greece. I also work as a planetary sciences educator at the Hudson River Museum’s planetarium. As I spend more of my time studying the sky and the origins of our understanding of astronomy, I am drawn to Mesopotamian astrology and its influence on western astronomy. Many of the Greeks’ ideas about the cosmos had their origins in Mesopotamian astrology. While studying our clay impressions here at the Morgan, I noticed that numerous seals depict celestial bodies, and the details of these scenes piqued my interest.

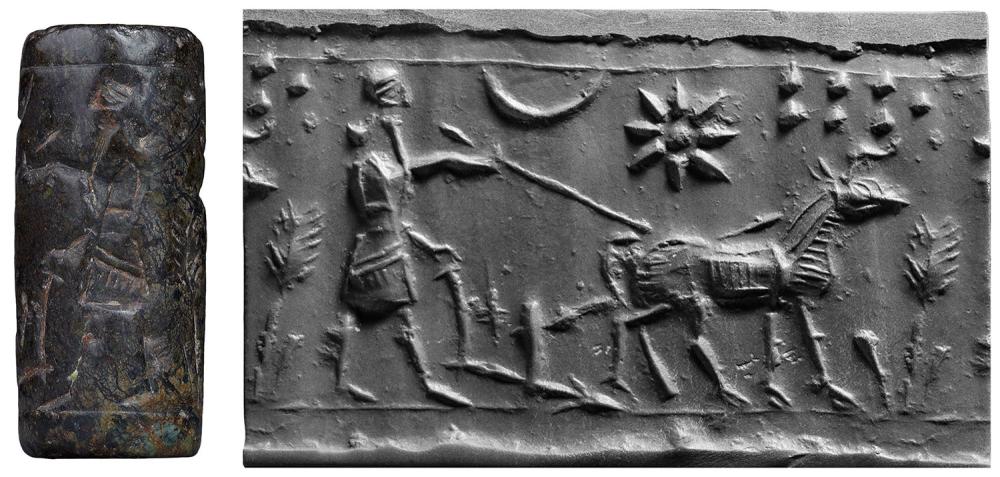

One seal in particular is astrologically notable: Seal 653, or “Man Prodding Plowing Ox.” At first glance, it appears to be a mundane scene of a farmer simply plowing his field. Upon closer inspection, there seems to be more to this scene that may give us insight into how Mesopotamians observed and documented celestial movements and how these movements were tied to agricultural practices of the time. According to Edith Porada, who published these seals at the Morgan, “the scene portraying a man plowing may nevertheless have a ritual significance... it depicts a rural ritual, in this case connected with agriculture.” In the sky above the “prodding man” is a crescent moon, sun, and a cluster of seven stars. The presence of these celestial bodies seems to establish a connection between agricultural practices and the cosmos; the seven stars, also known as “MUL.MUL” in Sumerian and “zappu” in Akkadian (or the Pleiades/Seven Sisters in the ancient Greek tradition) are associated with harvesting seasons in various cultures. This imagery suggests reliance on celestial observations to determine the best times for sowing and reaping crops. Additionally, the combination of the crescent moon and sun could also symbolize the passage of time, emphasizing the importance of natural cycles in these agriculturally dependent societies. This seal would have been carved during the Neo-Assyrian period, when astronomical interest had exploded among Mesopotamian royals who employed astrologers to observe, document and interpret celestial phenomena. This interpretation gives a fascinating perspective on how the motion of the cosmos may have been deeply ingrained in the daily lives of Neo-Assyrians.

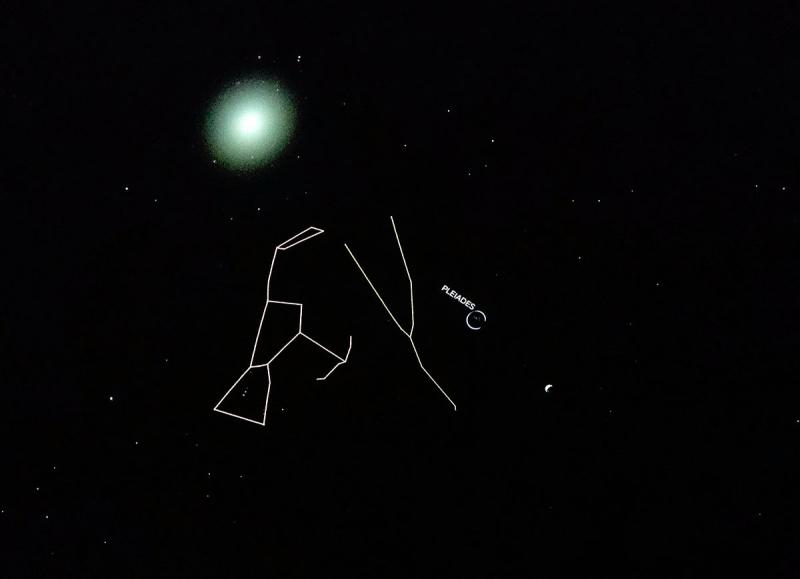

However, there is another possible interpretation of the image on this seal. It may not just represent the landscape of a field on Earth, but instead the entire landscape of the pre-dawn sky. The farmer may represent the constellation Anu the Shepherd (Orion, the hunter in Greek), while the ox he is driving represents the nearby constellation The Bull of Heaven ("GU4.AN.NA" in Sumerian or Taurus the Bull). The Pleiades sit in the sky directly next to Taurus. The placements of these on the seal mirrors their placements in the sky. The intricate carvings of this seal and the imagery they represent could reflect a sophisticated grasp of celestial bodies and the practical applications of this understanding. As spring approaches, these constellations begin to set earlier in the night, heralding the transition to warmer months. The depiction on this seal could thus illustrate not only a mythical narrative but also serve as a celestial map guiding the Mesopotamians in their agricultural and religious practices. This highlights the ingenuity and observational skills of ancient Mesopotamian people. Seal 653 stands as a testament to the harmonious blend of art, agriculture, and astronomy in Neo-Assyrian society. Such seals serve not only as artistic expressions but also as valuable records of the socio-cultural and scientific knowledge of the time.

Images taken by Katreena Lloyd at the Hudson River Museum planetarium.

These and other constellations that we have come to know through their ancient Greek and Roman names, have their origins in Mesopotamia. Through trade and travel much of what the Mesopotamians thought about the skies influenced the ancient Greeks. It is possible that Thales of Miletus, an early Greek philosopher traveled to Mesopotamia and brought new ideas back with him to Greece. Over two thousand years ago, Greco-Egyptian astronomer and mathematician Ptolemy wrote his treatise, The Almagest. This astronomical manual contained a catalogue of 48 constellations known throughout the Greco-Roman world. While this book was groundbreaking in early astronomy, Babylonian astrologers were already naming and documenting many of those same constellations in their own astronomical texts centuries before Ptolemy’s Almagest. For example, the constellation that Ptolemy documented as “Taurus the bull” was also known as the bull [of heaven] to Babylonian astrologers. Clay tablets, such as the Ritual for the Observances of Eclipses, inscribed with observations as well as rituals to be done during certain celestial events, were stored in libraries and archives in Babylon and Assur.

In Mesopotamia, early astronomy and astrology were intertwined. Scholars used their observations of the night sky for divination and religious rituals. Believing celestial bodies conveyed signs and omens that could impact human affairs, these scholars meticulously documented the movements and patterns of the heavens. They noted the positions of the stars, the phases of the moon, the wandering of planets, and the cycle of the sun to predict events on earth, from weather patterns to the outcomes of wars and the fate of kings. The religious significance of celestial phenomena cannot be overstated in Mesopotamian culture. The celestial bodies were seen as manifestations of deities, each with their own identity and influence.

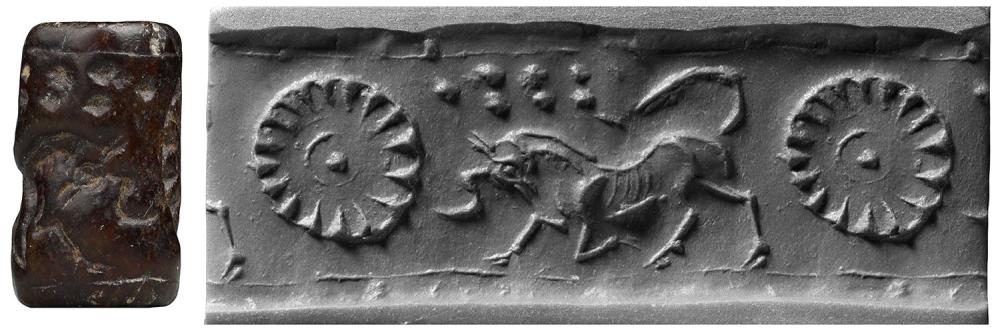

People in Mesopotamia assigned identities to many constellations, which have endured through the ages. The moon god Sin, the sun god Shamash, and the planet gods like Ishtar (Venus) played central roles in their cosmology. One example may be Seal 635, another seal that shows a bull (Taurus) with seven “stars” (the Pleiades). Observing and understanding the movements of these divine entities were essential for maintaining harmony with the cosmos and ensuring the favor of the gods. Many of these observations can still be read today in what are called the Babylonian Astronomical Diaries. These constellations were more than mere patterns of stars–they were imbued with mythological significance and used in various astrological readings.

The work of early Mesopotamian astronomers laid the foundation for the development of astronomy and astrology as we know it today. Birth charts, horoscopes, and the zodiac remain integral parts of astrology, demonstrating the lasting impact of Mesopotamian scholars. There is so much to explore about astronomy in ancient Mesopotamia. I am hoping to learn more about how the sky is depicted in Mesopotamian art and how they influenced the cultures around them, including the ancient Greeks.

Find out more about ancient astronomy at the Zodiac Project.

Katreena Lloyd

Academic Year Intern

Ancient Western Asian Seals & Tablets

The Morgan Library & Museum