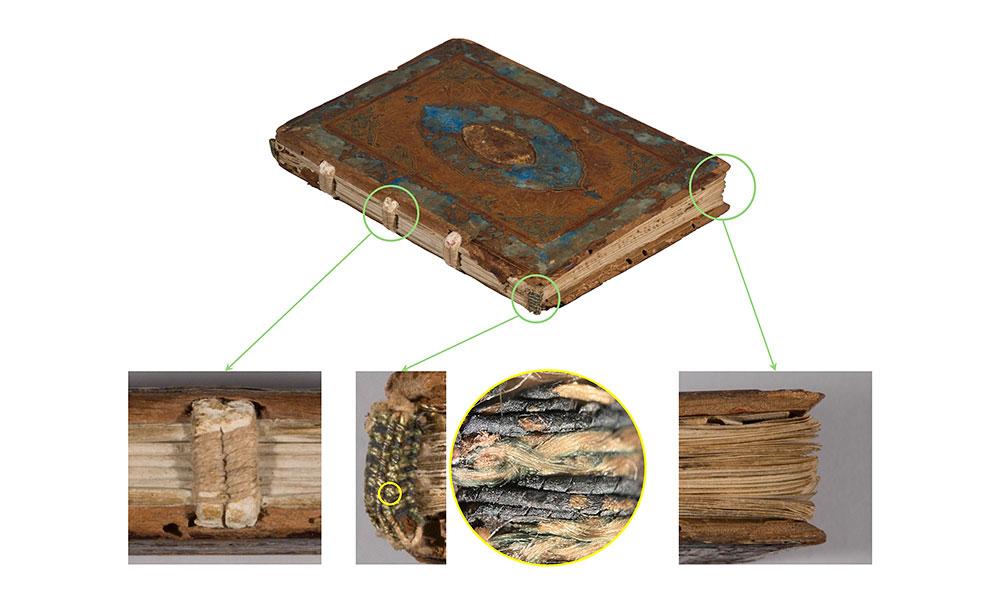

In late 2023, the Morgan Library & Museum acquired Codex Lippomano (PML 199044) from the Sotheby’s auction of the T. Kimball Brooker collection. This manuscript is the earliest known example of a plaquette binding from the Italian Renaissance, integrating Classical antiquity and Islamic decorative styles within an Italian structure (Hobson 1989; Figure 1). Despite its significance in book history, the binding has not been studied in depth, which prompted me to explore its structure and the materials used in the cover decorations.

The manuscript of about a hundred Latin poems by Jacopo Tiraboschi, written on parchment, was a gift to his classmate Niccolò Lippomano, preserving memories of their time at Padua University in the mid-1470s (Hobson 1989). Italy was in the midst of the humanist movement at this time, which focused on the study of Classical antiquity. The influence of Humanism is evident in the manuscript through its upright humanist script (Figure 2), which is distinctive from its predecessor, the Gothic script. This humanist influence also extends to the covers, as shown in the plaquette decoration.

A plaquette binding is decorated in the center of its cover with a relief impression, often a profile of a Classical figure or scene. In the Codex Lippomano, the central oval leather piece is stamped and inlaid in the wooden board. The figure is assumed to be a profile of Antinous, the lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian. Using multimodal imaging equipment, the depth of the raised design was captured in detail using the 3-D rendering feature (Figure 3).1 According to Anthony Hobson’s Humanists and Bookbinders (1989), the bookbinder of this manuscript is Felice Feliciano, a scribe and a passionate antiquarian based in Veneto, Italy. Regardless of the bookbinder’s identity, the use of a Classical motif at the center of the cover highlights the humanist’s appreciation for Classical heritage.

The binding’s uniqueness extends beyond its plaquette decoration. The rest of the cover is filled with Islamic-style decoration; this integration of the Islamic and Classical styles is rare. This period in Italy had a significant cultural wave influenced by Islamic decorative arts, driven by trade centered in Venice. Common decorative elements found in Islamic bindings include a central medallion with four corner pieces and vegetal filigree cutouts with contrasting-colored backings—as seen in examples of Islamic filigree bindings from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in the Morgan’s collection (Figures 4, 5, 6).2 The lobed almond profile with pendants in the Codex Lippomano likely references Persian bindings, which later transferred into the Mamluk and Ottoman bindings in the fifteenth century (Ohta 2012).

Italian bookbinders mimicked the Islamic style in decorations but did not adopt Islamic binding structures. The Codex Lippomano is bound in a typical fifteenth-century Italian binding with beveled wooden boards, three sewing supports lacing into the boards, and decorative secondary endbands. Considering all the different cultural influences on the binding, it is impressive how such a small book can encapsulate and represent its multifaceted contemporary context.

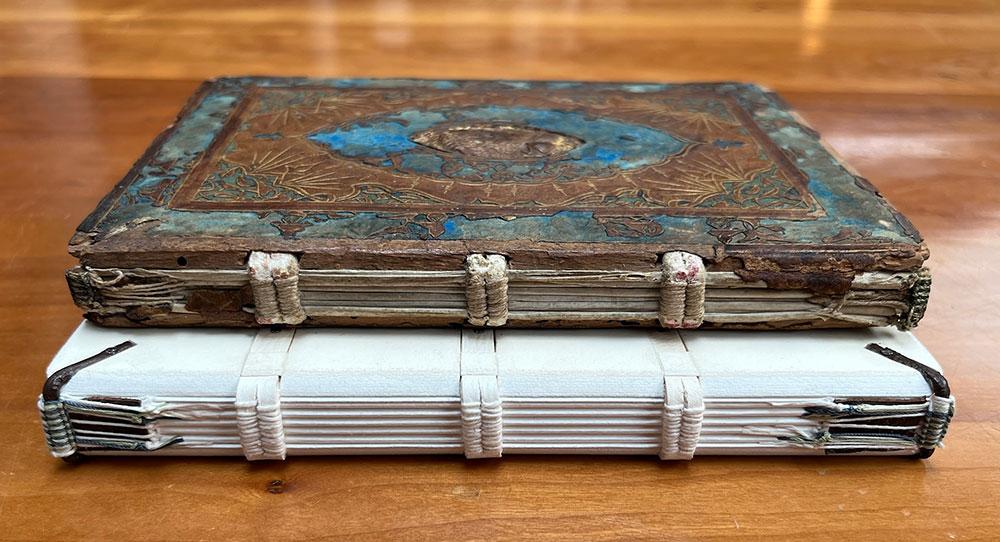

While studying the historical context and visual style of the decoration, I became intrigued by the cover's complex structure and its crafting process. The general structure of the decoration is as follows: a wooden board of the binding, blue and green backing layers, a leather filigree cutout, a plaquette relief, and tooling with brushed gold. I created diagrams to visualize the intricate layering of the decorations, which clarified their structure and original appearance (Figures 7–8). I then constructed a physical model of the binding, which serves as a hands-on educational resource. Creating this model was also an informative experience, as it allowed me to grasp the challenges involved in each step and assess what is feasible, especially when the original binding techniques are unknown. This process was complemented by in-depth examinations using the specialized equipment available at the Thaw Conservation Center. I will now outline the binding structure and share new findings on the materials used in the decorations.

Binding

The extensive wear and losses on the spine of the Codex Lippomano’s binding conveniently reveals the sewing structure. The parchment leaves were sewn together with linen threads on three alum-tawed thong supports (Figure 9-Left). The decorative endbands were sewn in a typical Italian Renaissance style, over multiple cores using alternating green silk and silver-wrapped threads (Figure 9-Center). Although the silver elements of the threads have tarnished to dark blue, X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis confirmed their composition as silver with some copper. Microscopic examination further revealed the silver foil wrapping around the silk core (Figure 9-Center).

The parchment textblock is connected to the edge-beveled wooden boards by alum-tawed supports that tunnel through the spine edges of the boards and emerge on the outer surface (Figures 9-Left and Right). The book was possibly covered in a single piece of leather first, and then a window cut out to accommodate additional decorative layers. It seems likely that the filigree leather was added separately from the leather cover, as it would be extremely difficult to position the delicate filigree accurately while covering the entire book.

In creating a book model, the aim was to replicate the original binding as closely as possible, though some steps and materials remain unknown (Figure 10). I also had to make some compromises due to the availability and affordability of the historical materials. For instance, the model textblock is made of paper leaves instead of parchment, and the wooden boards were replaced with laminated paper boards. The model has green and blue silk threads for the endbands, as I discovered the silver threads from the Codex Lippomano after completion.

Blue Backing Layer

All backing layers would have been prepared after the leather filigree was cut so they could fit precisely in the designated areas. The cutout blue layer was applied to back the central design and the border (Figure 13). The central oval piece was cut while attached to the wooden board, as the cut line on the blue paper closely aligns the socket on the wood, which was probably carved at this stage.

Questions arose about the material and pigment of the blue layer, as they were unclear due to aging and adhesive residue. When examining a tiny fiber sample under a polarized light microscope, I observed cross-markings typical of bast fibers from plants like flax and hemp, confirming that the blue layer is paper rather than parchment (Figures 11–12). Using the spectrometer function in the VSC8000-HS and a handheld XRF instrument, I identified the blue pigment as azurite, a widely used pigment during the Medieval and Renaissance periods in Europe.3 The spectrometer readings matched the standard azurite reference, and XRF analysis detected copper, a primary component of azurite.

For the model, I used acrylic paint on laid paper to visually match the blue to the most saturated color remaining on the Codex Lippomano.

Green Backing Layer

The cutout green silk layer was added to back the corner pieces (Figure 14). Since there is no visible overlap between the blue and green layers, it is unclear which was laid down first. The plain weave fabric is most likely silk, given the linear bundle of fibers without twists observed under the microscope (Figure 16).

Small Pieces of Blue Paper & Green Silk A set of small blue and green pieces was laid on top of each other’s ground, adding extra color to the decoration (Figure 15).

Leather Filigree with Blind Tooling and Shell Gold

The leather filigree was then placed on top of the backing layers, having been prepared and cut separately from the book. This is the most labor-intensive part of the decoration, as evident from the delicate filigree design. While it is possible to hand-cut individual decorations—I did so for the model—I initially wondered if the bookbinder used a punching tool or die to ease the process. After closer observation under the microscope, I am confident these are hand-cut, considering the extended cut lines in the removed areas (Figure 17). Although the general design repeats, no two shapes are identical.

My interest in creating diagrams started here. The filigree decoration on the Codex Lippomano has many losses, and I had an urge to reconstruct the complete design. Using photos of the covers, I recreated the pattern, filling in gaps, and used this design for the model by printing it on paper and attaching it to the back of a leather piece, cutting away the filigree with scalpels (Figure 18).

The cutout filigree has blind tooling and painted shell gold. In the diagram, you can see how adding gold significantly enhances the design (Figure 19). I assumed the tooling would be the final step of decoration, as it is in typical bookbinding, where it is called "finishing." However, when I attempted to tool around the intricate cutouts after cutting the filigree, I kept slipping into the cavities, making blind tooling very challenging. I now wonder if the design was blind-tooled first, then cut, attached to the cover, and finally brushed with shell gold.

When I consulted with Kristine Rose-Beers, Head of Conservation & Heritage at Cambridge University Libraries and an expert in Islamic bindings, she noted that no historical records detail these processes for Islamic bindings. However, this might be irrelevant since this binding was made by an Italian bookbinder who was merely copying the decorative style of Islamic bindings, not their techniques.

Plaquette Decoration

The impressed plaquette decoration was attached to the central oval socket of the wooden board (Figure 20). XRF analysis indicated the presence of calcium in the exposed filler area, suggesting a gesso-like material. The leather over the filler appears to be the same leather used for the filigree. The background of the profile was brushed with gold to emphasize the figure.

The bookbinder likely used a wood or metal intaglio stamp to create the plaquette impression. Based on my experiments, it seems the filler and leather were impressed individually, as stamping the soft filler and leather simultaneously did not give a crisp impression. It is more plausible that the impression was made in the filler first, and once it hardened, the leather was stamped over it.

For the model, I created a silicone mold from a cameo brooch and cast an acrylic filler (Figure 21). After the filler dried, I clamped a dampened piece of leather between the mold and filler to impress the design. Once the plaquette was trimmed and set in the socket, the profile background was painted with gold watercolor (Figure 22).

Red Beads

Finally, tiny red beads were added to the background of the plaquette profile, over the gold (Figures 23, 24, 25). The beads range in diameter from 0.5 to 1 mm and are hemispherical. Their material is undetermined, with suggestions of glass or resin.

The Codex Lippomano retains only a few red beads, but based on other bindings by Feliciano and the punched gilt ground, the background was likely fully filled with them originally. Hobson identified eight more bindings attributed to Feliciano, some of which also hold red beads (Figures 26–27).

I purchased red glass beads to cover the background of the profile, attaching them with wheat starch paste. The book model was completed with full decoration on the front cover and a cutaway on the back cover to reveal the layers beneath the leather filigree (Figures 28–29).

The manuscript is a surprisingly composite object, both culturally and physically, containing parchment, wood, leather, metal, paper, textile, and a few unknown materials (Figure 30). While some mysteries remain in the binding and its materials, the overall layering is now better understood through the diagrams and book model. I hope to continue researching to uncover the unknowns and gain a deeper understanding on the Codex Lippomano and other plaquette and filigree bindings of the period.

Yungjin Shin

Pine Tree Foundation Fellow in Book Conservation

Thaw Conservation Center, the Morgan Library & Museum

Endnotes

- The equipment used is VSC8000-HS, which combines digital imaging and multi-wavelength illumination. Examination techniques include multispectral imaging from ultraviolet to infrared light sources, transmitted light and raking light imaging, 3D topographical imaging, full-spectrum color analysis, etc.

- A filigree is an ornamental work of fine wire formed into intricate, delicate patterns or openwork designs.

- XRF model: Bruker Tracer III-SD.

Bibliography

- Hobson, Anthony. 1989. Humanists and Bookbinders: the Origins and Diffusion of the Humanistic Bookbinding 1459–1559 with a Census of Historiated Plaquette and Medallion Bindings of the Renaissance. Cambridge University Press.

- Ohta, Alison. 2012. “Covering the book: bindings of the Mamluk period, 1250-1516 CE.” PhD thesis, SOAS, University of London.