While searching the Morgan collections for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI)-related materials, I came across PML 185005. I was initially puzzled that a publication credited to American writer William Faulkner appeared in my “Philippines” keyword catalog search. The title: “Faulkner on truth and freedom: excerpts from tape recordings of remarks made by William Faulkner during his recent Manila visit.” Faulkner visited the motherland? Interest piqued, I headed to the vault, navigated to the object's location within the Carter Burden Collection, and carefully opened the clamshell box. Within I found a small, staple-bound pamphlet with a flimsy plastic dust jacket, published by the Philippine Writers Association in 1956. As I looked through the pages, a section titled “faulkner’s impression of filipinos” caught my eye.

In it, Faulkner states:

“I have always believed since I have been in your country that the people of the Republic of the Philippines are the best friends which my country has…We, in my country, know that the Filipino is a friend; we know there is a mutual dependence between our two nations, our two people.”

My immediate reaction to Faulkner’s words was mixed (much like my ethnic identity). On one hand, it was endearing to hear Faulkner’s experience of kinship with Filipino people. Being Filipino myself, I know firsthand the way we treat strangers as friends and friends as family. On the other hand, I was struck by the claim of a “mutual dependence” and Faulkner’s emphasis on “my country.” This language led me to question the context of his presence in the archipelago. What was the reason for his visit and for the subsequent transcription and printing of his lectures?

The first section of this post will examine Faulkner’s reported kinship with Filipinos in PML 185005 by introducing the concept of kapwa, a core value of Filipino Indigenous psychology that emphasizes interrelatedness and community. Then, I’ll dive further into Faulkner’s visit to the Philippines and investigate the propagandic nature of his travels within the context of the Cold War. The overarching intentions of this post are to introduce values of indigenous Filipino identity and critically question the context surrounding this printed pamphlet. In doing so, I contemplate this collection object as an example of the tension between authentic experience and propaganda presented in print culture.

Filipino kapwa

In the 1980s, Virgilio Enriquez founded Sikolohiyang Pilipino—a branch of psychology dedicated to indigenous Filipino concepts, attitudes, and behaviors—in an effort to consider Filipinos outside of Western models. Undertaking this cultural revalidation in the form of a new discipline led Enriquez to study indigenous Filipino groups and their IKSP (Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Practices). Through his research, he identified what is known among Pinoy scholars as a “core Filipino value”: kapwa. The value pervades every ethno-linguistic group within the Philippines. Kapwa is best understood as a sense of togetherness and shared human identity, a moral imperative to treat all human beings as kin, as friends, as equals.

Faulkner begins his remarks on the people of the Philippines by highlighting this friendship. In these printed transcriptions, Faulkner additionally discusses national language alongside recognition of Filipino friendship. Identifying the connection between language and cultural values is more insightful here than Faulkner may have realized. He insists that Filipinos embrace their heritage and language: “I think there is a great deal of beauty in any national language, national literature”; “The Filipinos have their own traditions of poetry in their folklore, in their language, in their dialects. This must be recorded, that is the job of the Filipino writer”. Unknowingly, Faulkner is illustrating pakikipagkwentuhan (storytelling) and its importance in Filipino literature and cultural production. Pe-Pua, discussing the legacy of Sikolohiyang Pilipino founder Enriquez, reinforces this notion: “It is in their own mother tongue that a person can truly express their innermost sentiments, ideas, perceptions, and attitudes” (2002, p. 60). The word kapwa is linguistically derived from two words: (1) Ka – refers to any kind of relationship, a union, with everyone and everything and (2) puwang – space. Kapwa encompasses the indigenous Filipino moral framework, emphasizing physical and emotional community space, collective needs being met, and identifying and welcoming “others” as part of a larger “us.” Tagalog, the national language of the Philippines, has countless words that similarly begin with the “ka-” prefix. This moral-linguistic connection epitomizes the sense of kinship embedded in Filipino and Filipino-American personhood.

Taking the transcriptions in “Faulkner on truth and freedom” at face value and considering the publication as an archival object documenting cross-cultural exchange, we get the sense that Faulkner instantly recognizes the imperative of the Filipino to be a friend. The pamphlet underscores the fondness Faulkner has toward Filipinos as well as his apparent interest in their cultural heritage. Ultimately, our Nobel Prize recipient gives the crowd exactly what they are craving: kinship with the illustrious Americans. But, by examining further context surrounding this visit and the author’s other State-funded travel, one begins to question how much of Faulkner’s words are authentic.

Cold War Propaganda

The image above was taken on August 25, 1955. It shows Faulkner on stage behind a heavily microphoned podium at the University of the Philippines addressing a sizable crowd of Filipino students and faculty, who seem quite serious and aloof to their eminent guest. Though we are not present, the tense energy of the room seems to leak from the image. After discovering the existence of Faulkner’s trip (and finding this confusing image), I questioned who or what brought him there to speak and why.

Deborah Cohn writes about Faulkner’s visit. His Manila trip, funded wholly by the U.S. government, was part of a larger world tour in the second half of the 1950s. Dubbing Faulkner the “globetrotting cold warrior,” Cohn elaborates: “the State Department capitalized on Faulkner’s international appeal, sending him as goodwill ambassador to Latin America (1954, 1961), Asia (1955), and Europe (1955, 1957), where he met with enthusiastic audiences in both allied countries and those where the U.S. government was seeking to improve foreign relations” (2016, p. 393). A-ha! Faulkner’s visit to the Philippines was not out of personal pursuits to learn Filipino culture, share wisdom, and befriend the locals. Rather, it was a short stop on a much wider-reaching, U.S. Cold War propaganda expedition.

Though the nation-building of the American colonial era brought prosperity to certain aspects of Filipino society, for many this prosperity signaled an “Americanization.” General anti-American sentiment birthed “Filipinization” movements in response. Nationalist sects included academics and intellectuals like Jorge Bocobo, Rafael Palma, Teodoro Kalaw, and Epifanio de los Santos, who developed and promoted ideologies of filipinismo. These nationalists were outspoken in their desires to disconnect from American influence and embrace kapwa and other pre-colonial value frameworks. Growing anti-American sensibilities during this time period is likely why Manila became a stop on Faulkner’s tour.

Authentic Experience Versus Propaganda

The State Department and United States Information Agency (USIA) sent Faulkner to Manila to discourage nationalism and dispel communism, all while boosting support for American democracy. Put simply, he was not sent to the Philippines to make friends with the Filipinos. Yet the PWA printed this pamphlet of Faulkner’s remarks, where he eloquently characterizes this friendship and “mutual dependence.” These printed words now have a permanent home in the Morgan’s vault.

Were Faulkner’s words part of a scripted indoctrination scheme by the United States who tasked the unlikely author with their delivery? Did Faulkner actually feel the kinship and closeness with his Filipino audience that he touted? Pareho kayang totoo? Can both of these things be true?

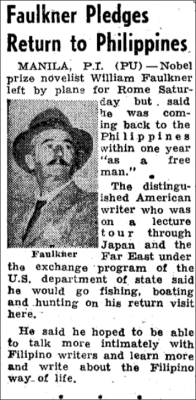

Propaganda is deliberately disseminated information that aims to influence the opinion of an audience. What is important is the intention: the information itself can be true or false but still presented in a propagandic way. What matters in a propaganda campaign is that information is being used as a tool to emotionally, politically, or otherwise affect the audience. In the case of Faulkner in the Philippines, it may well be the truth that the author felt the strong kinship he described with those attending his Manila lectures. There is evidence that Faulkner enjoyed his short time in the Philippines, but may have felt restricted in some ways. In the news clipping below (found by Jose Dalisay for PhilStar), Faulkner states that he had plans to return to fish, boat, and talk more intimately with Filipino writers “as a free man.”

News clipping quoting Faulkner's intentions to return to the Philippines to fish, boat, and talk more intimately with Filipino writers “as a free man.”

Through Faulkner’s own words, we know he enjoyed his trip to Manila and planned to return for personal pursuits. We also know that to a certain extent he lacked freedom during his trip there, despite finding friendship with his Filipino audience. Because a good relationship between the U.S. and the Philippines during the Cold War period benefited the U.S. and its goals of improving international favor, Faulkner’s expressed kinship was immortalized in this printed publication.

Conclusion

PML 185005 is undoubtedly propagandic in nature, yet it still expresses an authentic truth. The “mutual dependence” Faulkner preached was within his responsibilities as American goodwill ambassador on state-funded travel. But, I believe the experiences of kinship and his statements that the “Filipino is a friend” are rooted in his true encounters with the people. The tension between authentic experience and propaganda within print culture is inherent to the dissemination of information. The choices and actions involved in printing and publishing words are performances of power and agency by whoever is doing the printing. The discrepancies found within this particular object jumped out at me and made it obvious that I should question the nature of the text; not all information has such evident contextual depth. Analysis of this pamphlet has brought a valuable lesson to light and it is the takeaway I hope to leave with the reader: Question the information you receive and uncover as much context as possible. To take anything at face value is not an option, especially now as we all navigate daily through the bombardment of information in the many forms it takes.

Sam Mohite (she/her)

Belle da Costa Greene Curatorial Fellow

The Morgan Library & Museum

Endnotes

- In this writing, I use “Filipino” as a gender inclusive term because the term is inherently gender-less (despite its -o ending which indicates a masculine term in other languages). I have seen scholars use “Filipinx” and “Pin@y” in efforts to remove the “o/a” binary and be gender-neutral. These modern, westernized forms can also serve as umbrella terms to include members of the community from all gender identities and global locations in the same way “Filipino” does.

- This paragraph pulls almost directly from a previous research project of mine on the search and struggle for cultural heritage and identity in the Philippines throughout various stages of US colonialism. If interested, you can find the full paper here.

- I was able to get in contact with Jose regarding the source of the clipping that appears in both his article and blog post on the topic, but his response was as follows: “Very sorry but I don’t know either. I must’ve stumbled on that clipping somewhere online.”

Further reading

On kapwa scholarship, legacy and emerging

- Desai, M. (2016). Critical "Kapwa": Possibilities of Collective Healing from Colonial Trauma. Educational Perspectives, 48, 34–40.

- Labor, P. D. P., & Gastardo-Conaco, M. C. C. (2021). Viewing Your Kapwa: Elaboration of a Social-Relational Construct through Language. Philippine Social Science Journal, 4(4), 10–19.

- Lily, S., Jim, M., & Perkinson (2003). Filipino "Kapwa" in Global Dialogue: A Different Politics of Being-With the "Other"

- Pe-Pua, R., & Protacio-Marcelino, E. (2000). Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino psychology): A legacy of Virgilio G. Enriquez. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3(1), 49–71.

- Remoquillo, A. T. (2023). The Problem with Kapwa: Challenging Assumptions of Community, Sameness, and Unity in Filipina American Feminist Fieldwork. Alon: Journal for Filipinx American and Diasporic Studies, 3(1).

On Faulkner and his Cold War travels

- Blotner, J. (2005). Faulkner a biography. University Press of Mississippi.

- COHN, D. (2016). “In between propaganda and escapism”: William Faulkner as Cold War Cultural Ambassador. Diplomatic History, 40(3), 392–420.

- Oakley, H. (2004). William Faulkner and the Cold War: The Politics of Cultural Marketing. In J. Smith, D. Cohn & D. Pease (Ed.), Look Away!: The U.S. South in New World Studies (pp. 405–418). New York, USA: Duke University Press.

References

- Cohn, D. (2016). “In between propaganda and escapism”: William Faulkner as Cold War Cultural Ambassador. Diplomatic History, 40(3), 392–420.

- Dalisay, B. (2020, June 21). Faulkner in Manila. Philstar.com.

- Lagdameo-Santillan, K. (2018, July 24). Roots of filipino humanism (1)"Kapwa". Pressenza.

- Pe-Pua, R., & Protacio-Marcelino, E. (2000). Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino psychology): A legacy of Virgilio G. Enriquez. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3(1), 49–71.