In 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment prohibited the sale and transport of alcohol. Repealed in 1933, this brief period in American history, known as Prohibition, created a cultural movement that defined a decade and was known for its speakeasies, mob runners, and bootlegging. The roots of Prohibition can be traced to 1826, and the founding of the American Temperance Society.1 One of the movement’s supporters was Rev. John Pierpont. His involvement is heavily documented in his papers held here at the Morgan.

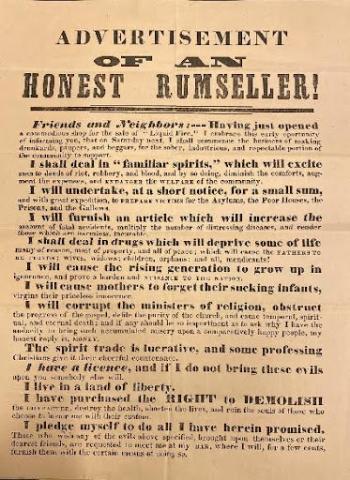

During the Second Great Awakening, as many northerners were leading the call for abolition, the ideology of a better society led many to believe that specific vices were part of a larger problem with America’s moral compass. To create a utopian society, abolitionists such as the Rev. Pierpont, John Greenleaf Whitter, and William Lloyd Garrison aligned themselves with the idea of temperance. Rooted in many protestant churches, the movement took on similar activities as the abolition movement. Meetings, publications, and the pulpit were ways in which reformers advocated, first for drinking in moderation, and then ultimately for total abstinence. Those fighting for abstinence would become known as teetotalers. Rev. Pierpont preached abstinence; he was also part of a group that felt that it was not only important to discuss the perils of drinking but to stop those who profited from the selling of liquor, such as rum sellers. It is interesting to note that the language used to call out these sellers was similar to the language used to call out the evils of slavery. This is one reason activists of the two movements became so intertwined. In abolition, while preaching on the inhumanity of slavery, those who participated and profited from the act were seen as destroying America’s values. In the fight for temperance, reformers used this same ideology to highlight the wrongs of profiting off the poverty, death, and abuses that were being connected with the dangers of drinking.

As he had regarding abolition, Rev. Pierpont took up his pen to spread his message on temperance. His poem, A Temperance Song – A Parody, provides a lighthearted take on the dangers of drinking. The satiric verse plays on the rhythm of a sea shanty, uplifting a sober lifestyle and all the benefits it brings.

Some love to roam

Where the glasses foam,

And the poison circles free—

But a chosen band,

In a rescued land,

And a Temperance Life for me.

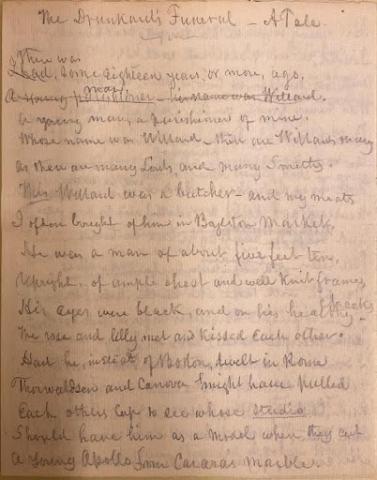

In A Drunkard’s Funeral, a much more somber work written in 1839, Pierpont forgoes poetic devices in favor of a matter-of-fact retelling of the grim realities of drinking. Describing the fall of a former parishioner, the tale not only speaks to the death of a man but the effects that his drinking had taken on his family.

Now, in all this, there is no poetry;—

The tale is simple fact, and simply told.

The hand of God,—that painteth evening's clouds,

The gloom of midnight, and the morning's glory,

Who poureth round the death-bed of the just

A light that prompteth him with dying voice

To cry, "O grave, where is thy victory?"—

This tale could be read as an early iteration of one of the most successful plays before the opening of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In 1844, William H. Smith produced the play The Drunkard at the Boston Museum.2 With 140 performances between 1844 and 1845, the show became the first in a long line of temperance theater works that entertained 19th-century audiences while also speaking on societal issues such as temperance, abolition, and women’s suffrage. It was known in 1844 that the play was co-written by Smith and a “literary gentleman.” Scholars now believe that the unnamed writer was John Pierpont, who likely would have wanted to remain anonymous due to the stigma tied to the theater community. It is interesting to note that only one letter exists between the two in the Reverend’s correspondence. And it was from the year 1844. Both the drafted tale and the play tell the story of a man who had allowed drinking to take over his life. Unlike Pierpont’s work, The Drunkard ends with the salvation of the main character, something the Reverend wished he could have done for the man in his tale.

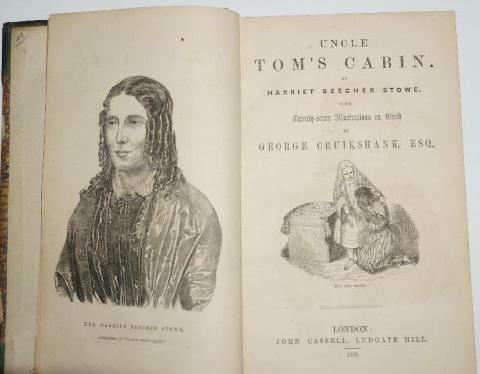

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896) Uncle Tom’s Cabin, London: John Cassell, 1852. The Morgan Library & Museum, bequest of Julia P. Wightman; PML 150858

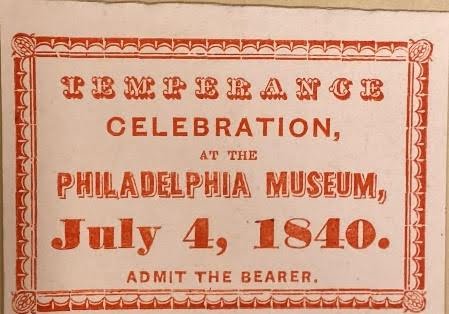

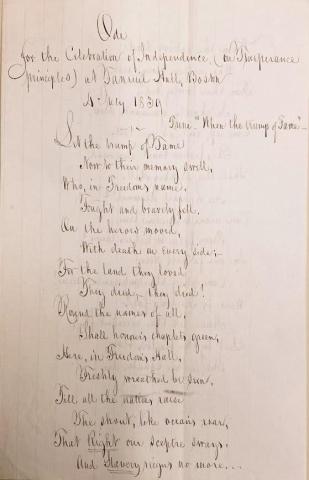

The play also shows a connection between the temperance movement and abolition, as most theaters who were willing to produce The Drunkard also produced Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a work which also has strong temperance themes. The first edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the Morgan’s collection was illustrated by temperance supporter George Cruikshank,3 yet another connection between those who supported both movements. In one of Rev. Pierpont’s most poignant pieces, abolition and temperance meet, just as they did for the audiences who saw both The Drunkard and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Written for a July 4, 1839 event at Faneuil Hall in Boston, Ode for the Celebration of Independence, (on Temperance Principles) calls for those in the audience to take the temperance pledge to protect freedom.

In the first verse, as he honors those who have died fighting for the moral compass of America, he writes:

Till all the nations raise

The shout, like ocean's roar,

That Right our sceptre sways,

And "Slavery reigns no more."

For Pierpont and other temperance abolitionists, the two causes were intertwined. Later he writes, “In our fathers' view, Come, pledge the Temperance Cause! Wine is Freedom's foe!”

Erica Ciallela

Exhibition Project Curator

The Morgan Library & Museum

Endnotes

- For more on the Temperance Movement and Prohibition see: Roots of Prohibition | Prohibition | Ken Burns | PBS

- Wm. H. Smith's Drunkard (virginia.edu)

- For more on Cruikshank and his temperance activities, see: Temperance – Digital Cruikshank (umbc.edu). The Morgan also holds several pieces of his work in the Peel Collection which J.P. Morgan purchased in 1900.