This essay serves as an expansion on the fall 2024 installation in the Rotunda that displays materials from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. The objects on view provide a glimpse into the intersecting worlds of astrology, politics, and abolition during the Civil War years in America.

The installation moves chronologically, investigating the evolving relationship between astrology and American society and highlighting the different categories of astrology that appeared in a variety of contexts during this time. Natural astrology was used in agricultural almanacs and judicial astrology was used in political horoscopes, foretelling the fates of individuals and nations; abolition-themed literature also featured astrological concepts. While seemingly disparate, both astrology and abolition encouraged individuals to see themselves as interconnected parts of the larger human race, united in the fight to end slavery.

Natural Astrology, Almanacs, and Abolition Literature

At its core, astrology is a system that interprets the positions of celestial bodies to explain and predict occurrences in the natural world. Astrology is a tool to turn mystery into meaning that has been carefully documented and carried down from antiquity through philosophers and was considered a science before the 17th century. Natural astrology considers the relation between the movements of the celestial bodies and natural phenomena on Earth (like weather patterns or natural disasters) and was the most widespread astrological framework used for activities like farming and personal care.

The almanac was an annual publication, descending from the tradition of medieval calendars and printed primers; the information essential for natural astrology forms the historic foundation on which almanacs were constructed. The publication of almanacs in America, like most intellectual endeavors of the colonial period, was a reflection of happenings across the pond in England. Printed and distributed across English (and eventually American) households, annual almanacs contain important information like calendars noting significant feast days for that year. Both the solar and lunar calendars provided insight into crop cycles. The lunar calendar was always included with what came to be known as the “Zodiac Man”, “Man of Signs”, or “the anatomy”, which illustrated a direct connection between the zodiac signs and body parts.

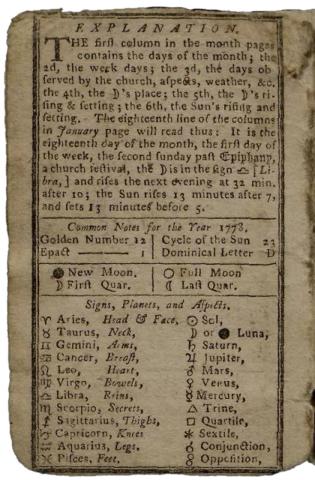

A 16th-century example is shown here with a 19th-century illustration to its right. This type of zodiacal association is referred to as medical astrology or iatromathematics, which asserted that body-zodiac correlations were beneficial in the diagnosis and treatment of personal ailments. The invention of the telescope in the early 17th century led to a divide within society, separating scientists pursuing astronomy from those with a more spiritual pursuit of astrological interpretation. But, despite rapid scientific developments in both astronomy and medicine, almanacs continued to include both natural and medical astrology information well into the 18th and 19th centuries.

The installation highlights two almanacs from the Gilder Lehrman Institute collections. The first is a pocket almanac from 1778 whose cover asserts its publication in “the third year of American Independency.” Inscribed by William Ellery, a Founding Father of the United States and one of the fifty-six signers of the Declaration of Independence, this almanac is 10 cm tall and was likely an object kept on his person for regular reference. The first page shown here has a small, condensed version of the anatomy.

The Lancaster Pocket Almanac, for the Year 1778 Lancaster, PA: Francis Baily, [1777]; Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History; GLC06669

The American Anti-Slavery Almanac was published annually from 1836 to 1843 by the American Anti-Slavery Society, a nationwide abolitionist group led chiefly by Frederick Douglass with members such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Their almanac not only compiled calendars and natural astrology information but also featured antislavery literature, advertisements, and artwork. The abolitionist almanac was published over sixty years after Ellery’s almanac, yet it still includes the same rendering of the anatomy. Regular use of the astrological information within these types of almanac publications promoted the visibility of the antislavery cause and informed the general public about enslaved people’s rebellions and relevant political speeches.

Judicial Astrology and Political Prediction

Rapid industrialization, polarizing moral division over slavery, and the apocalyptic atmosphere of impending war seemed to attract the public to more obscure and occult interests. Judicial astrology is the practice of prediction and forecasting based on the movements of celestial bodies. Astrologers began to appear in both Northern and Southern newspapers, advertising their predictive capabilities to the general public seeking answers or hope in confusing times. These news clippings from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History archive show such advertisements.

Astrology’s presence in the mainstream expanded from almanacs and personal inquiries to larger-scale political affairs. Judicial astrologers appealed not only to the general public, for whom they claimed to predict love and careers, but also to political figures, for whom they claimed to foresee battle outcomes and election results. Political astrology—or mundane astrology—is the branch of astrology dealing with politics, government, and laws. Political astrologers took on a wide-ranging clientele, some as prominent as figures like William H. Seward, an American politician who would go on to serve as United States Secretary of State. In a Senate speech about the North and the South tensions in 1850, he spoke the following:

“I discover no omens of revolution. The predictions of the political astrologers do not agree as to the time or manner in which it is to occur…According to the horoscope of the honorable senator from Mississippi (Mr. Foote), it was to take place on a day already past” (from “Speech of the Hon. WM H. Seward, in the Senate of the United States” 1850 printed in Collection of Antebellum Pamphlets 1840–1850; GLC 09233).

One of the most prominent political astrologers of the time period was Luke Broughton (1828–1898). He is best known for his publication Broughton’s Monthly Planet Reader and Astrological Journal, a periodical dedicated to the prediction of election outcomes and the personal lives of political figures. The images below display four issues from 1860 that printed the birth chart of each presidential candidate, two of which are included in the exhibition. Particularly fascinating within this periodical is Broughton’s erroneous prophecy that “Douglas will be very likely to come off conqueror after all, as he has the strongest Nativity of the whole four candidates.”

Broughton’s Monthly Planet Reader and Astrological Journal 1, nos. 5 (August 1860), 6 (September 1860), 7 (October 1860), and 8 (November 1860); Philadelphia: L. D. Broughton, 1860; Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History; GLC 09014

Though political predictions of the Civil War period such as these often fell short of truthful, the propulsion of astrology into the mainstream did not cease. The desire to know the unknown, predict the unpredictable, and find safety in a secure future can be found within us all, in both a Civil War soldier in 1864 and you, the reader, in 2024. This installation chronicles how astrological concepts grew to become foundational to the lifestyles of many Americans, from the everyday workers in the middle class to the Senators of a troubled nation. Being within an election year, it is easy to understand the uncertain feelings that drew so much of the American public to astrology during this period in history and why it remains present in mainstream discourse today.

The installation, Astrology, Politics, and Abolition in Civil War Americana, is on view in the Rotunda of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library from September 10, 2024, through January 12, 2025.

Sam Mohite (she/her)

Belle da Costa Greene Curatorial Fellow

The Morgan Library & Museum