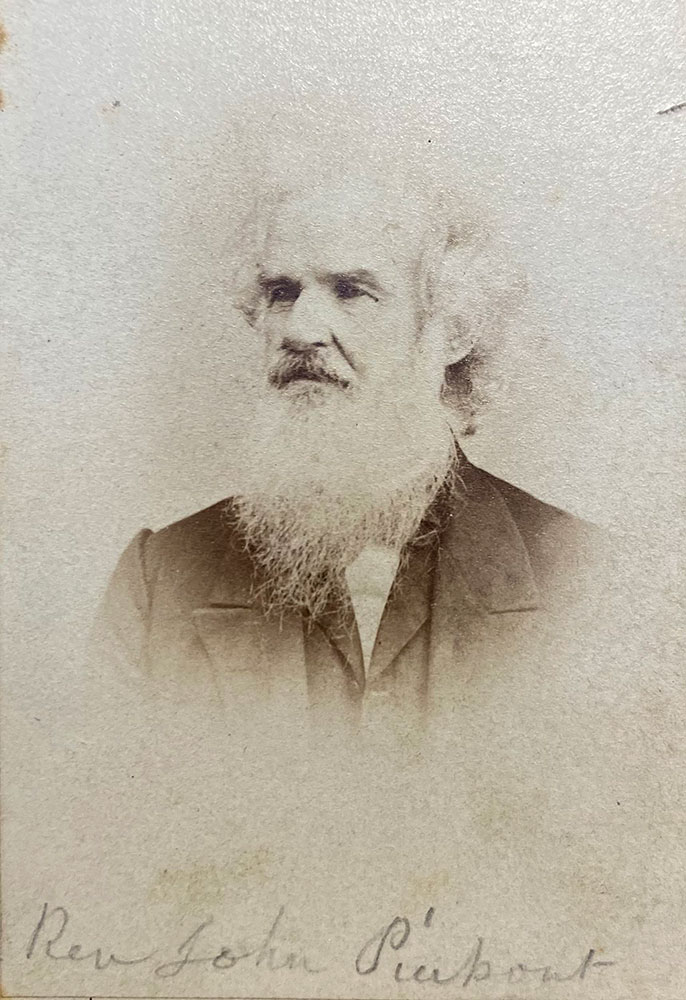

The Reverend John Pierpont [photograph], ca 1857–1866. Photographic print; 4 x 2 1/2 in. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; ARC 1197.21

During the early nineteenth century, the Second Great Awakening swept across the United States. The Protestant religious revival offered a backdrop for three key movements that helped define the nineteenth century. Abolition, temperance, and spiritualism were seen as social catalysts to form a more perfect society. This post will be the first of three exploring each of these movements through the eyes of J. Pierpont Morgan’s grandfather Rev. John Pierpont, whose papers are preserved in the Morgan archives.

Having spent time researching these movements, I was surprised when combing through the Morgan archives to find all three represented in an unlikely group of papers. The Morgan archives are home to several Morgan family members’ papers, including those of J. Pierpont Morgan, Jack Morgan, and Anne Morgan. But it is also home to those of Morgan’s maternal grandfather, the Rev. John Pierpont.1 Rev. Pierpont has been called the poet of the abolitionist movement, and his papers provide a unique opportunity to explore one man’s deep belief in how America could live up to its founding promises.

Born in 1785 in Litchfield, Connecticut, the Rev. Pierpont would become known for his steadfast belief and support for abolition, the movement to end slavery in America. It is most likely that his support for abolitionism stemmed from his time spent in South Carolina as an educator before becoming a minister. As the Unitarian minister found himself at the center of the growing anti-slavery movement, it was clear that not all northerners were supportive of the cause. In fact, Pierpont would leave his first church, Hollis Street Church in Boston, due to the backlash he received for his outspoken devotion to ending slavery. His beliefs not only affected his ministry but put him at odds with family members such as his son James, who would choose to support the confederacy during the Civil War. After the controversy at Hollis Church, the reverend moved to Troy, New York, which became a popular meeting place for abolitionists and anti-slavery meetings. He would eventually move back to Medford, Massachusetts to continue his work as a reformer and minister. His papers include correspondence with many noted abolitionists, such as the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, Gerrit Smith, one of “the secret six"2 that helped fund John Brown’s Raid, and the Rev. Samuel May, a leader in the abolition movement and uncle to Louisa May Alcott. His correspondence shows his involvement in the burgeoning movement, with many letters discussing anti-slavery meetings and sermons that spoke to the evils of slavery. Along with his correspondence, Pierpont collected numerous clippings of materials from pamphlets, newspapers, and anti-slavery meetings. But one of the most intriguing parts of this collection is the numerous folders of Pierpont’s poetry that not only discuss his religious thoughts, but also his appeal for the end of slavery.

Pierpont began writing poetry early in his career. One of his most famous works, ‘Airs of Palestine,’ published in 1816, was so popular that it helped fund his education at Divinity School. Of the poem, the writer Edgar Allan Poe remarked, “The Rev. J. PIERPONT, who, of late, has attracted so much of the public attention, is one of the most accomplished poets in America. His ‘Airs of Palestine’ is distinguished by the sweetness and vigor of its versification, and by the grace of its sentiments.”3 His 1843 collection of anti-slavery poems includes a passionate work, entitled ‘The Tocsin, with the opening verse,

WAKE! children of the men who said,

‘All are born free!’—Their spirits come

Back to the places where they bled

In Freedom's holy martyrdom,

And find you sleeping on their graves,

And hugging there your chains,—ye slaves!4

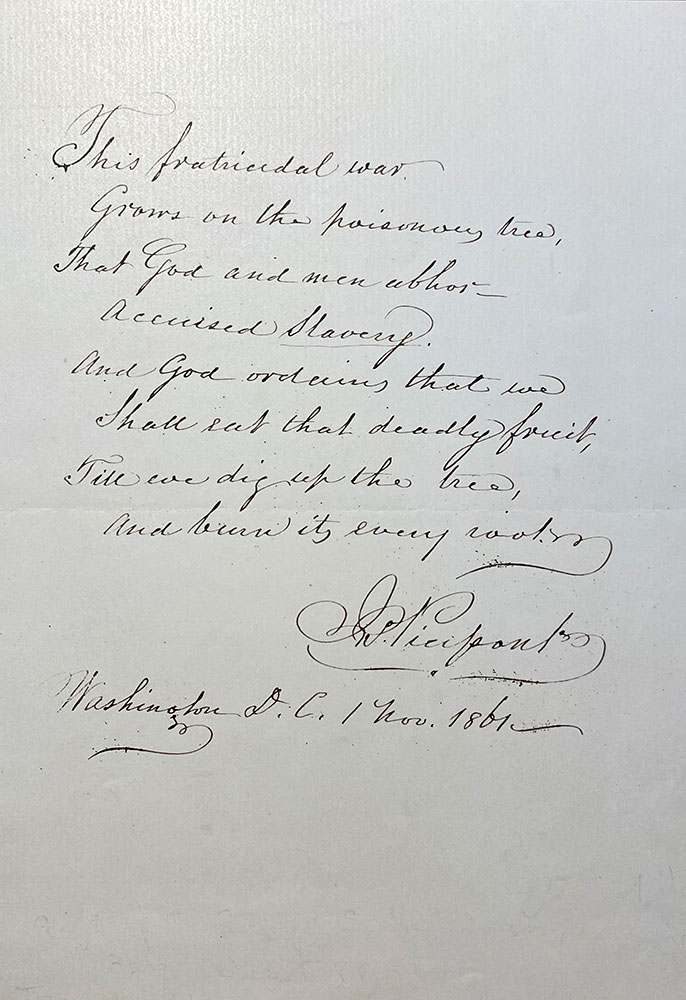

The poem begins with an epigraph: “‘If the pulpit be silent, whenever or wherever there may be a sinner, bloody with this guilt, within the hearing of its voice, the pulpit is false to its trust.’—D. WEBSTER.” This poignant and strong statement establishes Pierpont’s unwavering belief that one should speak up against the injustices they see. He believed that his position within the church was important and that his vocation as a minister obliged him to pursue reform. In September of 1861, the seventy-six-year-old enlisted in the 22nd Massachusetts regiment to serve as a Chaplain during the Civil War. He wished to serve in any way he could to help end slavery. While enlisted, the reverend and poet penned a short verse that vividly captures his sentiment on the raging war:

This fratricidal war

Grows on the poisonous tree,

That God and men abhor—

Accursed Slavery.

And God Ordains that we

Shall eat that deadly fruit,

Till we dig up the tree,

And burn it, every root.

This Fratricidal War by Rev. John Pierpont. November 1, 1861. The Morgan Library & Museum; Arc 726 Box 13 Folder 7.

His words make the clear and pointed argument that change must come from the root in order for slavery to end and equality to begin. Drawing on the Bible, Pierpont and many abolitionist writers presented the image of a tree that was unnatural or non-native to the landscape, with its fruit representing corruption and the evils of slavery.5 Upon first reading this poem, it immediately reminded me of Abel Meeorpol’s poem “Strange Fruit,” popularized as a song in 1939 by singer Billie Holiday. Also evoking the image of America as a poisoned tree, Holiday’s recording of “Strange Fruit” was a rallying call to end the brutal lynchings of African Americans during Jim Crow and became a powerful record of the ongoing injustices and violence against African Americans.6

Pierpont’s poems capture one man’s conviction to see his country uphold its promise of equality. His work was often recited at antislavery meetings, and he was included in a collection of writings published by the Rochester Anti-slavery Society titled Autographs of Freedom.7 His dedication to the cause led Quaker poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whitter to pen a poem in his honor in 1843. Rev. John Pierpont died in 1866, but not before he was able to see the news of freedom reach those enslaved in Texas, the farthest confederate state on June 19, 1865.

Erica Ciallela

Exhibition Project Curator and former Belle da Costa Greene Curatorial Fellow

The Morgan Library & Museum

Endnotes

- The John Pierpont Papers are a part of the Morgan Archives (ARC 726): John Pierpont Papers (themorgan.org).

- The secret six were a group of abolitionist who helped raise the funds for the 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry.

- Letter from John Pierpont to John Keese (poemuseum.org).

- A copy of Reverend Pierpont’s Anti-Slavery Poems is preserved in the Morgan Archives (ARC 834).

- For more on the symbolism of the Liberty Tree and the Tree of Slavery, see Jared Farmer’s “In America, trees symbolize both freedom and unfreedom,” OUP blog

- To learn more about the history of the song “Strange Fruit,” see this essay (PDF).

- A copy of Autographs for Freedom is preserved in the Morgan Archives (ARC 841).