Diary of a Marriage: Sophia (1809–1871) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864). Newlyweds Sophia Peabody and Nathaniel Hawthorne chose to keep a diary together, making a joint record of intimate life in their new home.

Diary of a Marriage: Sophia (1809–1871) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864). Newlyweds Sophia Peabody and Nathaniel Hawthorne chose to keep a diary together, making a joint record of intimate life in their new home.

About the Diary

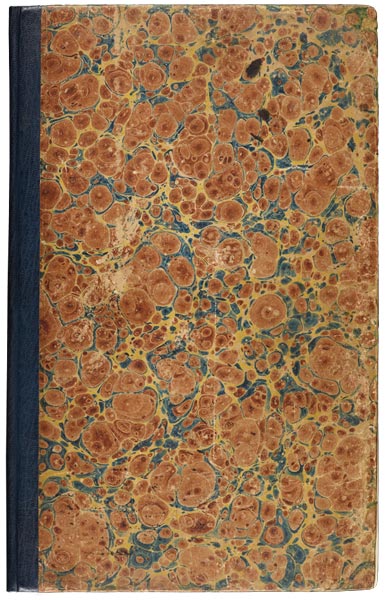

For the Hawthornes, journal keeping was a family affair. Both Nathaniel and Sophia kept private records periodically throughout their lives, and when they married in July 1842 they began to keep a journal together, each making entries in turn. They wrote in the same notebook—a small blank volume with marbled-paper covers and a leather spine—read each other's entries, and built a joint narrative of their intimate life as partners in their new home, the Old Manse in Concord.

"A rainy day—a rainy day," begins Nathaniel's first entry in their joint diary, "and I do verily believe there is no sunshine in this world, except what beams from my wife's eyes." While he teased Sophia about her hopeful disposition, he embraced his own new role as spouse with a sense of ease. "It is usually supposed that the cares of life come with matrimony;" he wrote, "but I seem to have cast off all care, and live on with as much easy trust in Providence as Adam could possibly have felt before he had learned that there was a world beyond his Paradise."

For her part, Sophia exalted in the physical pleasures of their union. When spring came, she compared nature's rebirth to her own awakening. "Oh lovely God!" she wrote, "I thank thee that I can rush into my sweet husband with all my many waters, & sing & thunder with all my waves in the vast expanse of his comprehensive bosom—How I exult there—how I foam & sparkle in the sun of his love. . . . I myself am Spring with all its birds, its rivers, its buds, singing, rushing, blooming in his arms. I feel new as the Earth which is just born again—I rejoice that I am, because I am his, wholly, unreservedly his." After Nathaniel's death, Sophia blotted out some of her own words in the notebook as she prepared her husband's journals for publication, but she left enough of herself uncensored that her soaring voice remained present.

As the seasons passed, the Hawthornes marked them together. "This is Thanksgiving Day," Nathaniel wrote on November 24, "a good old festival, and my wife and I have kept it with our hearts, and besides have made good cheer upon our turkey, and pudding, and pies, and custards, although none sat at our board but our two selves." When summer came, both tried their hand at gardening, and Sophia mocked her artistic husband as she observed him with rake in hand. "Dearest husband," she wrote, employing the formal language they often used to address each other, "thou shouldst not have to labour, especially with the hands, & thou hatest it rightfully. Thou art a seraph come to observe Nature & men in a still repose, without being obliged to exert thyself in clearing away old rubbish." Despite Sophia's protests, Nathaniel succeeded in bringing forth enough asparagus for dinner, and one day they shared a watermelon with Henry David Thoreau when he came for dinner.

On the first anniversary of their wedding day, the Hawthornes addressed love letters to each other within the diary. Sophia—pregnant with the couple's first child—recalled their lives the year before: "Then we had visions & dreamed of Paradise. Now Paradise is here & our fairest visions stand realized before us." Nathaniel, despite his chosen profession, felt powerless to capture the moment on paper: "life now heaves and swells beneath me like a brim-full ocean, and the endeavor to comprise and portion of it in words is like trying to dip up the ocean in a goblet."

When their first notebook was full, the Hawthornes began another—this one taller and narrower, but with a similar cover. In the first entry, Sophia wrote with joy of the arrival of their first child, Una. "It was great happiness to be able to put her to my breast immediately," she wrote, "& I thanked Heaven I was to have the privilege of nursing her." As the years went by and two more children were born, the Hawthornes contributed less and less to their common diary, but the changes to their family became physically evident in the volume. On the endpapers, the children added scribbles and drawings, and one day in 1852 eight-year-old Una made her own entry—a very short story about two little children taken in by a kind old lady after their parents died. She signed it, "Yours lovingly, Una."

When their first notebook was full, the Hawthornes began another—this one taller and narrower, but with a similar cover. In the first entry, Sophia wrote with joy of the arrival of their first child, Una. "It was great happiness to be able to put her to my breast immediately," she wrote, "& I thanked Heaven I was to have the privilege of nursing her." As the years went by and two more children were born, the Hawthornes contributed less and less to their common diary, but the changes to their family became physically evident in the volume. On the endpapers, the children added scribbles and drawings, and one day in 1852 eight-year-old Una made her own entry—a very short story about two little children taken in by a kind old lady after their parents died. She signed it, "Yours lovingly, Una."

Cover of the marriage diary of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne (1809–1871) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864), 1842–43. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

Cover of a diary of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne (1809–1871) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864), kept after the birth of their first child, 1844–52. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

Diary of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne (1809–1871) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864), with an entry by their daughter Una, s1844–52. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.