Charlotte Brontë (1816–1855) relied on her diary to escape stifling work as a schoolteacher; Tennessee Williams (1911–1983) confided his loneliness and self-doubt; John Steinbeck (1902–1968) struggled to compose The Grapes of Wrath, and Bob Dylan (b. 1941) sketched his way through a concert tour.

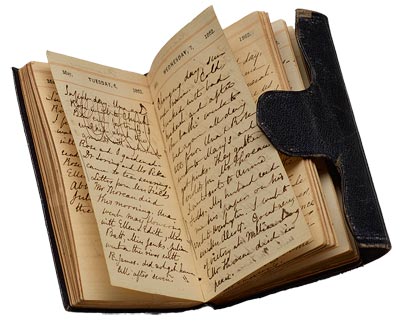

For centuries, people have turned to private journals to document their days, sort out creative problems, help them through crises, comfort them in solitude or pain, or preserve their stories for the future. As more and more diarists turn away from the traditional notebook and seek a broader audience through web journals, blogs, and social media, this exhibition explores how and why we document our everyday lives.

With over seventy items on view, the exhibition raises questions about this pervasive practice: What is a diary? Must it be a private document? Who is the audience for the unfolding stories of our lives—ourselves alone, our families, or a wider group? The diaries on view allow us to observe, in personal terms, the birth of such great works of art as Nathaniel Hawthorne's novel The Scarlet Letter and Gilbert & Sullivan's opera The Pirates of Penzance. Momentous public events from the Boston Tea Party to the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center are marked by individual witnesses. Many diarists, such as Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) and John Newton (1725–1807), former slave trafficker and author of the hymn "Amazing Grace," look inward, striving to live with integrity. Three great artists in their twenties, all on the brink of fame—Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), Charlotte Brontë, and Kingsley Amis (1922–1995)—hone their considerable talents in their private writings. And century after century, many individuals—from the famous diarist Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) to Abstract Impressionist painter Charles Seliger (1926–2009)—capture memory and mark time by keeping a daily record of the substance of everyday life.

EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS

The centerpiece of the exhibition is the seminal journal of Henry David Thoreau, whose dozens of marbled-paper covered notebooks record his well-examined life. Like many diarists writing over many centuries in a variety of forms, Thoreau sought "to meet the facts of life—the vital facts—face to face." Thoreau's monumental journal stands alongside the beautifully printed first editions of the confessions of St. Augustine (354–430) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), both transformative figures in the history of self-examination and self-revelation. The exhibition illustrates that even before the era of web diaries, many writers envisioned (or invited) an audience. The marriage notebooks of American author Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864) and his wife, Sophia (1809–1871), for example, were interactive documents. The newlyweds made entries in tandem, reading each other's contributions and building a joint narrative of their daily lives, from Nathaniel's first contribution—"I do verily believe there is no sunshine in this world, except what beams from my wife's eyes"—to Sophia's breathless declaration "I feel new as the earth which is just born again." Later, their young children added naïve drawings to the pages of their parents' notebooks transforming the marriage diary into a family affair.

Anaïs Nin (1903–1977)—one of the twentieth century's most prolific diarists—made a thick copy of her astonishingly intimate personal account, presenting to a friend "this uncut version of the Diary in memory of our uncut uncensored confidences and faith." Nin is one of several featured examples of diarists who sought a wide audience through traditional publication before the advent of the web. William S. Burroughs (1914–1997), a prolific diarist, published one of his journals during his lifetime—The Retreat Diaries (1976), a dream log he kept during a two-week Buddhist retreat in Vermont. Even Queen Victoria (1819–1901) released a volume of excerpts from her journals. A signed copy of her 1868 bestseller Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands is on view.

Some diarists turn their private writings into shared memoir. Fanny Twemlow (1881–1989), a British woman imprisoned in a civilian internment camp during World War II, copied the illustrated diary that she kept secretly and transformed it into a cherished family memento. Lieutenant Steven Mona, who led a police rescue-and-recovery team after the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, recast his private diary as a letter in order to share his experience with family and friends. "I don't think I will ever look at anything in life the same way," he wrote.

The diary has long served individuals as a place of emotional haven. Twenty-year-old Charlotte Brontë, working as a schoolteacher at Roe Head School in 1836, wrote diary entries in a minuscule script on loose sheets of paper, combining autobiographical narrative with flights of fictional fantasy that helped her endure emotional isolation. Some years later sitting in a classroom in Brussels, she opened a geography textbook and scrawled a diary entry on one of the endpapers, confiding her loneliness and bitterness: "It is a dreary life—especially as there is only one person in this house worthy of being liked—also another who seems a rosy sugarplum but I know her to be coloured chalk."

Tennessee Williams, too, relied on his diary in times of loneliness. In February 1955 he made his first entry in a cheap Italian exercise book with a cover featuring white polka dots on a blue background: "A black day to begin a blue journal." With Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in rehearsal and a new production of his acclaimed play A Streetcar Named Desire about to open in New York, Williams was nevertheless full of anxiety and increasingly dependent on drugs and alcohol. At the height of his literary success, he carried the journal from New York to Rome, Athens, Istanbul, Barcelona, and Hamburg, recording physical and emotional distress, frequent sexual encounters, and a debilitating creative impasse. "Nothing to say except I'm still hanging on," he wrote.

The great Scottish novelist Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832) did not begin a diary until late in life, when he was already one of Europe's most famous men and shortly before a countrywide financial crisis forced him to spend the rest of his life furiously writing himself out of debt. Over a period of six years, the journal became a crucial outlet for the feelings of despair—the "cold sinkings of the heart"—that had agonized him from the time of his youth. Even as he revealed his most intimate feelings, Scott made clear that he had decided to "gurnalize," as he called it, not only for his own benefit but also for "my family and the public."

One of those who read and benefited from Scott's revealing journal was English art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900), who kept a diary in 1878 of his feelings leading up to a severe mental collapse. After he recovered, he meticulously re-read his diary, marking it up and indexing it in search of warning signs to help him anticipate future breakdowns. He left several pages dramatically blank, heading them with just a few words—"February to April—the Dream"—an allusion to the nightmarish visions he had endured over several months.

The diary as a stimulus to creativity is represented by an extraordinary illustrated journal of American painter Stuart Davis (1894–1964), working journals of novelist John Steinbeck, a journal/sketchbook of English painter Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), and a travel diary of Albert Einstein (1879–1955) that is full of mathematical jottings. A diary of Nathaniel Hawthorne includes this idea for a story subject: "The life of a woman, who, by the old colony law, was condemned always to wear the letter A, sewed on her garment, in token of her having committed adultery." Hawthorne, of course, later developed this germ of a story—first documented in his diary—into one of the most celebrated of American novels.

While today's new media facilitates ever more frequent diary entries—sometimes updated hour by hour—the exhibition features examples of diarists similarly committed to continuous life documentation. In Bob Dylan's verbal and visual diary of his 1974 concert tour with The Band, he sketched a hotel room in Memphis and added a line of poetry: "Exploding galaxies of the red white & blue pulsing in the night of the big eye." Abstract Expressionist painter Charles Seliger (1926–2009) kept over 150 notebooks over many decades, rarely allowing a day to go by without recording activities, thoughts, and opinions, until his death in 2009. Seliger wrote in the tradition of the most famous English diarist—Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) —whose record of daily life in seventeenth-century London became a nineteenth-century bestseller. The Morgan holds the corrected proofs for the first published edition of Pepys's diaries—evidence of the longstanding human impulse to read other people's diaries.

In his working journal for The Grapes of Wrath, on view in the exhibition, John Steinbeck articulated the challenge of presenting an uncensored version of oneself: "I have tried to keep diaries before, but it didn't work out because of the necessity to be honest." While today's online diaries and social media profiles encourage the creation of carefully managed self-portraits, the impulse to deliberately craft one's identity in the diary is nothing new.

The exhibition is accompanied by an online feature exploring a selection of diaries in detail, a podcast series of readings from the diaries, and a blog that explores issues related to diary keeping both past and present.

![]() This exhibition is sponsored by CastleRock Management.

This exhibition is sponsored by CastleRock Management.

Generous support is provided by Liz and Rod Berens and by The William C. Bullitt Foundation.

Diary of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne (1809–1871), 1862. Gift of Lorenz Reich, Jr., 1980.