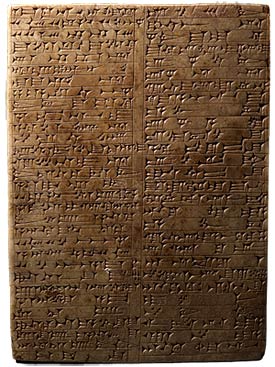

An inscribed tablet from the Middle Assyrian period of Mesopotamia records and commemorates the restoration of the temple of the goddess Ishtar in the capital city of Assur. The extremely rare object is on loan from a private collector and is part of a special exhibition of inscribed ancient Near Eastern stone objects.

The tablet was made during the reign of King Tukulti-Ninurta I, ca. 1243 B.C.–1207 B.C. He was notable for his conquest of Babylon, which made him the first ruler to ensure full Assyrian supremacy over all of Mesopotamia, as well as for an extensive building program in Assur, which included the restoration of the temple of Ishtar.

The inscription on the tablet records the king's deeds and conquests, as well as his ancestors, and describes the ruined state and restoration of the Ishtar temple. The inscription concludes with a curse on anyone who would attempt to remove the king's name from the tablet.

In addition to the tablet, other ancient Mesopotamian objects on view in the exhibition include: a stone bowl dating to about the twenty-fifth century B.C. with a dedication inscription in Sumerian; a stone foundation tablet dating to the twenty-first century B.C. with the name and titles of King Ur-Namma in Sumerian; an "eye stone" amulet with an inscription of King Kurigalzu I in Sumerian, ca. early fourteenth century B.C.; and another "eye stone" amulet with an inscription of King Nebuchadnezzar in Akkadian, ca. 604 B.C.–562 B.C. All of the items are part of the Morgan's notable collection of ancient Near Eastern artifacts, which were of great interest to Pierpont Morgan.

The exhibition explores the development of writing in Mesopotamia—the wedge-shaped system that we call cuneiform—that was in use for over three thousand years. The system, based on the use of syllables, proved so efficient that it was used for a number of different languages, including Sumerian, Akkadian, Hittite, Assyrian, and Babylonian. With the collapse of the ancient civilizations of the Near East understanding of the writing system was lost and it was not deciphered until the 1860s.

This installation is made possible by a generous gift from Jeannette and Jonathan P. Rosen.

Stone Foundation Tablet with a Historical Inscription of King Tukulti-Ninurta i in Assyrian.

Gypsum alabaster, Mesopotamia, Middle Assyrian period, Reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I (ca. 1243–1207 B.C.).