The Morgan holds in its collection two letters handwritten by Helen Keller in 1890, one of which is currently on view in the East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library. Keller’s lifetime of accomplishments, despite having lost her sight, hearing and speech at a very young age, are already familiar to most people. Yet this letter, written when she was only ten years old, provides extraordinary material evidence of her determination to overcome barriers to communication and engage with the outside world.

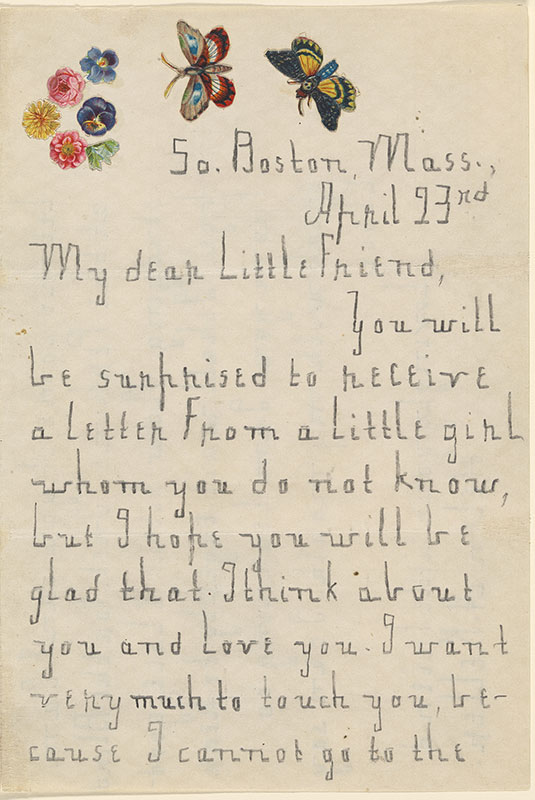

Figure 1: Helen Keller (1880–1968), Letter to Elsie Leslie, [South Boston, Mass.], 23 April 1890. The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Miss Jane Douglass, 1978; MA 3897.

The letter’s recipient was celebrity child actress Elsie Leslie, who was acting in a dramatization of Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper, on tour at the Hollis Street Theater in Boston. Keller explained in the letter that she could not attend the play because she could not see or hear, but asked if she could visit Leslie. “I want very much to touch you”, she wrote.

At first glance, Keller’s letter, with its decorative butterfly and flower collage, looks like typical childhood correspondence of the pre-digital era. Her carefully formed pencil lettering tells the story of a ten-year-old girl excited by the visit of a national celebrity to her town. But we can also look beyond the text to understand something more about the creation of the letter itself. In the conservation lab we shone a variety of lights on the letter to reveal some stories about the making of the paper it was written on, and the technique Keller used to form the text.

Conservators use light in a variety of ways to investigate the history and condition of objects in their care. In the case of the Keller letter, these different light sources showed us some features that were a little out of the ordinary.

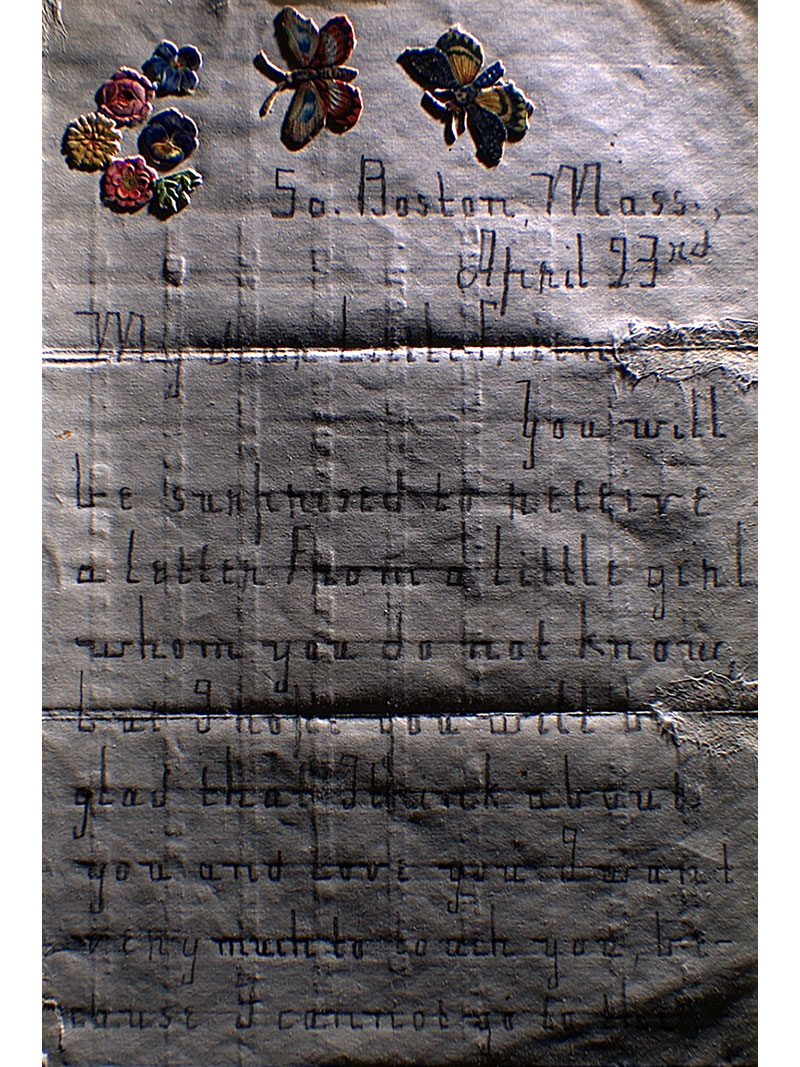

Under normal light conditions, the attentive observer notices an indistinct pattern covering the surface of the letter. When we looked at the sheet with light transmitted through from the other side, the pattern was accentuated, allowing us to see it more clearly (Figure 2).

In traditional, pre-industrial Western paper, a design inherent to the paper sheet is known as a watermark. A watermark is made with bent wire sewn into the papermaking mold. When a layer of wet paper pulp is formed in the mold, the paper fibers are less concentrated in the areas of the wire design, allowing more light to pass through when the sheet has dried.

With the invention of the paper-making machine at the turn of the nineteenth century, a new technique was needed to introduce watermarks into paper. Machine-made paper was manufactured in continuous lengths that passed through the machine on a moving wire screen. The problem of how to watermark machine-made paper was solved around 1826 with the invention of the dandy roll, a wire-covered roll adorned with a pattern or symbol.

The dandy roll passes over the already-formed sheet while it is still somewhat wet, pushing out water at the same time as pushing aside paper fibers to impart a design. Rather than being inherent to the formation of the sheet like a traditional ‘true’ watermark, the dandy roll watermark is pressed into one side of the paper from above as it passes from its wet state to the drying phase. When we looked at one side of the letter under raking light, the pattern was almost imperceptible (Figure 3). Raking light applied to the other side of the sheet, however, reveals the texture of the pattern very clearly impressed into one side of the sheet, showing where the dandy roll has come into contact with the paper (Figure 4).

The ‘watermark’ design provides a decorative aspect to the writing paper, particularly when held up to light. But the letter also has another textural element with a story to tell, this time about how Keller, overcoming her blindness, could form letters of the alphabet legible to a sighted reader.

In normal light it is apparent that the letter has an unusual embossed texture, but in combination with the watermark pattern and the text, it is difficult to discern its purpose. Under raking light it becomes apparent that the sheet is covered in evenly spaced, horizontal and vertical embossed lines (Figure 5).

When a raking light image is viewed in tandem with transmitted infrared light, we can see that the embossed lines align with the lowercase letters on the other side of the paper (Figures 6, 7). This is a clue that Keller was somehow using the tactility of the grooves in the paper so that her sense of touch could guide her writing.

Fortunately, we have historical evidence from Keller herself which further explains how she managed to write so clearly and “keep the lines straight.” A scrapbook from the Perkins School of the Blind archive contains a letter in which she explains how she pressed her writing paper into a board covered with parallel grooves. An image of a similar board can be found here.

By pressing the sheet into the grooved board, Keller formed indented lines in the paper, providing a tactile guide for letter formation. She explained that the small letters are made between the grooved lines, “while the long arms extend above and below them.” The resulting style of writing was known as ‘square-hand’. The raking light and transmitted infrared images show us the extent to which Keller mastered this technique: we can clearly see that the lowercase letters are all formed precisely within the indented lines. “It is very difficult at first,” she wrote, but “after a great deal of practice we can write legible letters to our friends”. 1

A week after her initial correspondence to Elsie Leslie, Keller wrote a follow-up letter revealing that her request to visit the actress had indeed been granted. “You cannot imagine how happy it made me to touch your lovely hair, and sit beside you in the chair,” she wrote.

Keller’s childhood letters in the Morgan’s collection are testament to her extraordinary discipline and dedication to language and communication. When we look carefully at these objects using varied light sources, we can more fully appreciate the painstaking and highly skilled work of a young girl determined to participate in the popular culture of her time.

Elizabeth Gralton

Sherman Fairchild Foundation Fellow

Thaw Conservation Center

The Morgan Library & Museum

Endnote

- Helen Keller, Letter to St Nicholas, in Helen Keller Newspaper Notices [unpublished scrapbook], vol. 1, 1887–1893, Samuel P. Hayes Research Library, Perkins School for the Blind, accessed 4/11/2024.