“The conditions of study are exceptionally well ordered; the reference library is so near completeness and the books so accessible, that for comparative study of literature on manuscript painting, there is no European library which is as convenient.” —Prof. Meyer Schapiro, Columbia University1

When the Pierpont Morgan Library (today the Morgan Library & Museum) opened to the public on October 1, 1928, the largest part of its Reference Collection was shelved in its Reading Room, which occupied the east side of the newly constructed Annex. In 1929, according to Belle da Costa Greene, the Morgan’s first librarian and director, the room contained more than 8,000 books. While scholars enjoyed ready access to the volumes at ground-floor level, the collection was arranged by old-fashioned fixed location. A book was tagged with a shelf mark, indicating the room, bookcase and shelf where it was kept. But as new acquisitions came in, books moved to different shelves. Shelf marks were changed frequently, and after the majority of the collection was shifted over 1936 and 1937, the staff struggled to revise the card catalogs.

What was needed was a classification to number the books in relation to each other based on subject, without reference to the shelves. No published scheme was found suitable. Of the leading contenders, Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) lacked depth in the areas of book history and the visual arts, while Library of Congress Classification (LCC) arranged subject matter in ways that would have been unhelpful. But elements of these could be adapted, and similar special libraries—including those of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Grolier Club, and Brooklyn Museum—had devised their own classifications, which were studied by the originator of the Morgan system.2

Morgan Reference Classification (MRC) was inaugurated by an Englishman named J.D.A. (John Denton Ashworth) Barnicot (1907–1981). Barnicot was recommended to Greene by the paleographer E.A. Lowe, whose library and archives are preserved at the Morgan today. Oxford-educated, and a specialist in Old Slavonic books, he had been Senior Assistant at the Bodleian Library prior to joining the Morgan in October 1938. During the year he was with the Library, he authored the first draft and began to reclassify the collection. After he left, the schedule was revised and expanded by Jean McKean Murphy, Head of Art and Music for the Queens Borough Public Library system and a former instructor of classification at Columbia University’s School of Information. After working closely with the Morgan’s curators and its head cataloger, Virginia V. White, Murphy produced the first typescript manual in 1941.

The Morgan scheme was broadly patterned after the thirteenth edition of Dewey Decimal Classification, parts of which were transposed or adapted.3 Like DDC, MRC features three-digit numerical notation, and following the class marks, numbers to the right of a decimal point specify further detail. But in MRC the call numbers are kept short, and subjects are developed to meet the requirements of the collection, rather than along strict hierarchical lines. Barnicot ordered the subject classes within a Dewey-like 000–999 framework, to conform to a Morgan which was very different than it is today. The call number sequence began in the old Reading Room (today Morgan Stanley Gallery East), extended through a basement stack room and the Print Room (then located in J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library), and ended in Belle Greene’s office, which is today a gallery known as the Librarian’s Office.

After a reclassification project in 1941, two sections covered most of the ground floor of the Reading Room: Manuscripts (class marks 100–199) and Iconography (201–208).4 Following numbers for the history of the book, writing, and conservation, Paleography (105–137) provides for both script and non-illuminated manuscripts; these numbers were originally transposed from a table in Universal Decimal Classification (003 Writing).5 In MRC the topic is divided by language—Greek (108), Non-Greek Eastern European (110), and Western European, Latin and National Tongues (111–137). Greek, Latin, and certain Western European schools are subdivided by period and script (figure 4).

Manuscript illumination (140–199) opens with numbers for general treatment (form material such as dictionaries), and ornaments, initials, and special subjects (for example, 141.7 Model books, drawings). Each of the national schools of illumination is subdivided into individual and small groups of manuscripts, and these are arranged chronologically by century. Each century has its own date letter (fourth to seventeenth centuries = D–T), and within these letters, under the sub-class .4, the manuscripts are simply listed according to catalogers’ judgment (figure 5). Additionally, manuscripts may be classed by place of execution and century within national schools, or by genre or subject (for example, 199 A = Apocalypse, 199 S = Biblia pauperum, 199.4 = Herbals, 199.5 = Bestiaries).

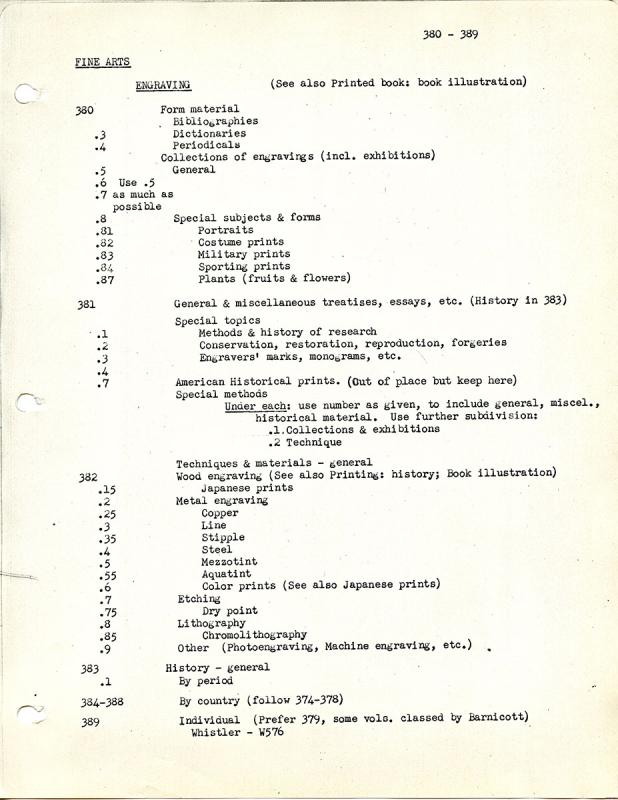

Figure 7. MRC, 1941. Engraving. The class mark 389 (individual printmakers) is today rarely applied, with 416 (artists’ individual biography) preferred. Referenced in the note, the number 379, which was for artists’ monographs concerned with drawing and engraving, is no longer used; books classed here were changed to other numbers. (Barnicot’s name is misspelled.)

Iconography (201–208) brings together a wide range of literature concerned with the meaning of visual images, with extensive coverage of both secular and religious subjects (figure 6). By the late 1930s Virginia White had developed an elaborate list of local subject headings, and a subset of these (iconography + subject) grew in parallel with the schedule.

In the beginning, Religion and Philosophy (210–299) was shelved in the Reading Room Gallery, as many of the Morgan’s manuscripts are devotional in nature. Here, MRC’s sections on Christian religion, monastic orders, the Bible, and service books were all adapted from Dewey. Elsewhere, MRC’s 500s (history, geography, etc.) were closely derived from DDC’s 900’s. MRC frequently uses these country numbers to subdivide topics, incorporating Dewey’s mnemonic principle. For instance, MRC’s base number for French history is 544, and the number “44” in a notation often signifies that the subject relates to France in some way. (For example: French drawing, 374.4; Book collecting, France, 846.44.)

Fine Arts (300–399) and Decorative Arts (400–414) were also shelved in the Gallery, with the exceptions of Drawing (370–379) and Engraving (380–389 [figure 7]), which were held in the Print Room. In its geographical/chronological breakdowns and definitions of special subjects, MRC resembles LCC, though its range is far narrower, and where possible material is collected under a single number.6 For example, where LCC treats religious, mural, still-life, landscape, and portrait painting as separate subjects, in MRC these are sub-classes, both under a general number for painting by special subject (342), and in the divisions for painting by country. MRC also arranges artists’ monographs alphabetically under one number (416), unlike LCC and DDC, where, for instance, works on Degas’s sculpture are subordinated under sculpture itself. (A notable exception is Photography, where monographs on individual camera artists are classed under 397.1.)

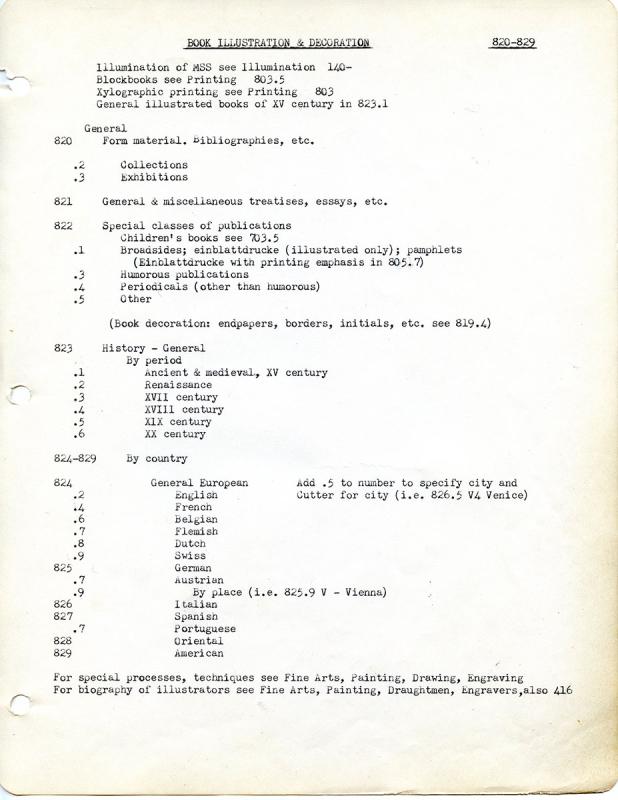

Works on the history and art of the printed book (800–885) were, for the most part, housed in Greene’s office: the North Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, where thirty-six bays ran along two tiers. At floor level were works on printing history (800–816). Along the balcony were works on the book arts and book collecting, including catalogs of libraries and private collections (some were also in the stack), along with a section devoted to Morgan history (900s). Following a section on xylographic printing and block books (803), printing history is arranged chronologically by century. Each century has country divisions, which are broken down further by bibliographies and collections, place, and printer. Incunabula (804–811) gives particular consideration to Gutenberg, the Aldine Press, and Caxton, and further provides for special subjects (including broadsides, indulgences, and the Missale Speciale). In its treatment of book illustration (figure 8) and bookbinding, MRC bears some resemblance to Grolier Club classification.7

Under Virginia White’s guidance, MRC was continually refined and expanded. Although designed for a collection which was much smaller at the time, the system still works well. It may be argued that the ease of obtaining ready-made call numbers from Library of Congress catalog records outweighs the advantages brought by a local classification.8 But the Reference Collection holds a good deal of material not held by LC, and benefits from MRC’s specificity and order.

What became of Barnicot? He left the Morgan for the New York branch of the British Library of Information after the outbreak of World War II, and later returned to England, where he enjoyed a long career as Director of the British Council’s Books Department. There are numerous references to him in the diaries of the novelist Barbara Pym, whose good friend he was for more than forty years.9 The two became friends after Barnicot started work at the Bodleian in 1932. A scholar of Slavic languages and cultures, he had recently concluded a traveling fellowship in the Balkans. Pym, who was six years younger, was pursuing a degree in English literature at St. Hilda’s College.

Figure 10. Virginia Villiers White (1902-1990) began her forty-year career with the Morgan in January 1927. Head of the Reference Cataloguing Department, she was supervisor of both the Reference Collection and the card catalogs. White was a graduate of the University of Michigan. (Portrait from The Michiganensian yearbook, 1922.)

In the summer of 1934, following her graduation, Pym began to write a comic novel, in which she imagined the lives of herself, her sister, and many of her Oxford friends in thirty years’ time. This eventually became her first book, Some Tame Gazelle (1950).10 In it, Barnicot is cast as the enigmatic John Akenside, an expert in Central European affairs who is accidentally killed during a riot in Prague. Akenside never appears directly in the story—he is already dead when it begins.

Today, a first edition of Some Tame Gazelle is preserved in the Morgan’s vaults, while a reprint is shelved in the Reference Collection, classified according to the scheme Barnicot originated.

Peter Gammie

Head of the Reference Collection

The Morgan Library & Museum

Endnotes

- Pierpont Morgan Library, A Review of the Growth, Development and Activities of the Library During the Period between Its Establishment as an Educational Institution in February 1924 and the Close of the Year 1929 (New York: Privately printed for the Pierpont Morgan Library at the Plandome Press, 1930), p. 8.

- Report to the Board of Trustees of the Pierpont Morgan Library, for the Year Ending December 31st 1938. Typescript. Administration Records: Reports and Minutes of Board Meetings, 1924–1960. The Morgan Library & Museum.

- Melvil Dewey, Decimal Clasification and Relativ Index, 13th ed. (Lake Placid Club, N.Y: Forest Pres, 1932).

- Barnicot’s original outline included a section (001–099) for miscellaneous Reading Room reference works (dictionaries, encyclopedias, etc.). During revision, it was decided to class these books according to the regular subject sequence and shelve them in a separate part of the room.

- International Institute of Documentation, Universal Decimal Classification, Complete English ed., 4th international ed. (Brussels: Keerrberghen, 1936–1939).

- Library of Congress. Classification Division, Classification. Class N: Fine Arts, 3rd ed. (Washington: Government Printing Office, Library Branch, 1922).

- Grolier Club. Library, The Classification Used in the Library of the Grolier Club, (New York: [The Gilliss Press], 1910).

- Roberto C. Ferrari, “The Art of Classification: Alternate Classification Systems in Art Libraries.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 28 (2): 73–98; David J. Patten, ed., “Library Classification Systems and the Visual Arts.” Supplement, ARLIS/NA Newsletter, vol. 4, no. 4/5 (Summer 1976): S1–S12.

- Barbara Pym, A Very Private Eye: An Autobiography in Diaries and Letters, Hazel Holt and Hilary Pym, eds. (New York: Dutton, 1984); Radmila May, “Barbara Pym in Henley.” Contemporary Review, 268 (February 1996): 87–90. Also available online

- Barbara Pym, Some Tame Gazelle (London: Jonathan Cape, 1950); Yvonne Cocking, “Who’s Who in Some Tame Gazelle: Paper Presented at the 18th North American Conference of the Barbara Pym Society Cambridge, Massachusetts, 12–13 March, 2016,” The Barbara Pym Society, accessed February 14, 2024.