Objects on view in J. Pierpont Morgan’s library reflect the past, present, and future of building collections in four curatorial departments, comprising illuminated manuscripts from the medieval and renaissance eras, five hundred years of printed books, correspondence and literary manuscripts, as well as printed music and autograph manuscripts by composers. These selections, which rotate three times a year, provide an opportunity for Morgan curators to spotlight individual items in different ways—to consider their historical and aesthetic contexts, and some of the stories behind these artifacts and their creators. Along with copies of the Gutenberg Bible and one of the world’s most important medieval jeweled bindings, here are some highlights of the current rotation on view in the East Room.

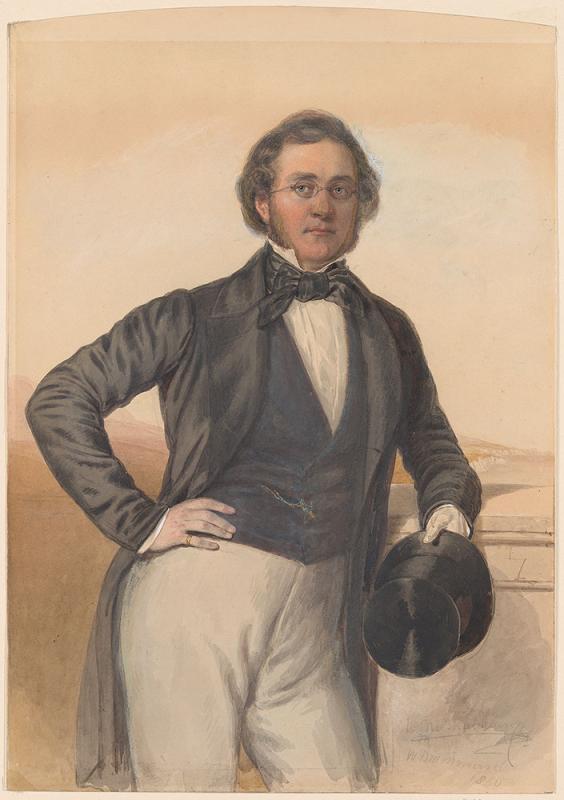

Thackeray’s Manuscript of Vanity Fair

Memorable pages on view from Thackeray’s manuscript of Vanity Fair (MA 479) introduce the central character of the novel, the talented, beautiful, and ruthless Becky Sharp, as she departs Miss Pinkerton’s Academy for Young Ladies. Like all the graduates of the academy, Becky has received a copy of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary from the self-important Miss Pinkerton. Becky, however, pitches her copy out of the window as her coach rounds the corner: an act that presages her relentless rise in society entirely through her own machinations, with no need for either male or female guidance along the way.

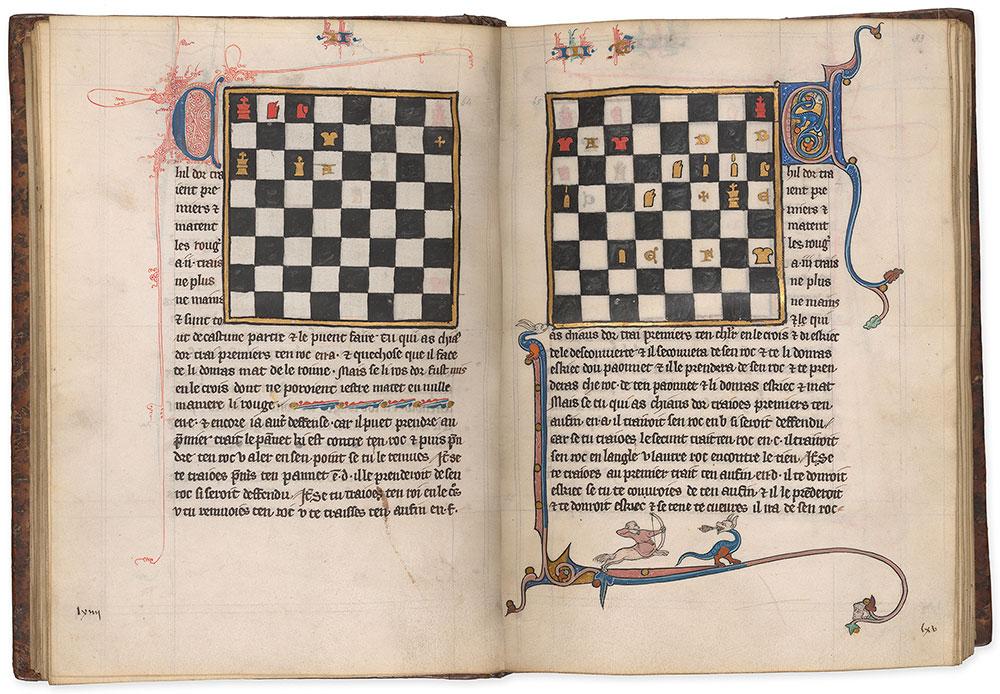

A Good Companion

The title of this treatise on chess and other board games derives from the anonymous author’s original Latin introduction: “I, a good companion [bonus socius], falling in with the wishes of my companions. . . . ” The upper half of each page features a diagram of a board game, with the pieces positioned to illustrate the problem explained in the text below. The margins are richly decorated, inhabited by figures and animals both real and imagined.

A Song for the Ages

This book’s parchment pages, metallic paint, and gold leaf evoke medieval manuscripts, but the volume is a modern creation by the artist Barbara Wolff. It contains both the Hebrew text and the English translation of the Song of Songs, a poetic dialogue between two lovers that is part of the Jewish Tanakh and the Christian Old Testament. Instead of featuring depictions of the lovers, each chapter of the Hebrew text begins with a metaphor for their love, written in gold ink. The full-page miniature to the left interprets that passage. Here, gold-and-red flames burn despite the silver-gilt blue waves. Grapevines illustrate other pages of text, along with more flowers and precious spice boxes in the English section.

Picturing the World

Agnese, a Genoese cartographer based in Venice, produced some of the most beautiful and accurate coastal atlases of the sixteenth century. Intended for educated readers, his atlases helped codify and disseminate a new understanding of the globe, including recent cartographical information about the Americas. This chart depicts the Atlantic Ocean with Central and South America on the left and Africa on the right. Brazil and Peru are clearly marked, but the Yucatán is shown as an island, rather than a peninsula, and the southwestern coast of South America (present-day Chile) is left blank. Lines radiate from the central compass rose, evoking the winds that help carry travelers to harbors across the seas.

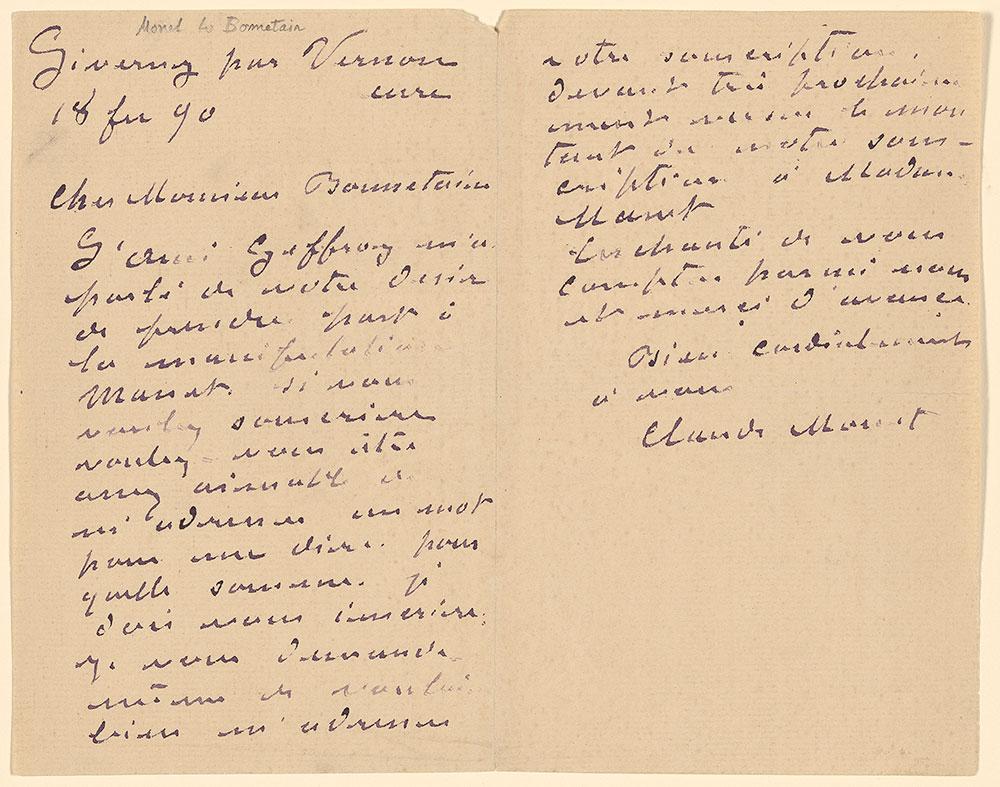

A Gift to the Nation

When Édouard Manet first exhibited his painting Olympia in 1865, it was not a success. Not only were viewers shocked by the nudity and forthright expression of the central figure—modeled by Victorine Meurent, a painter herself—they also criticized Manet’s use of color and perspective.

Monet and his peers felt differently. This letter to Bonnetain, a writer, is part of a fund-raising drive that Monet initiated in the late 1880s with the aim of purchasing Olympia from Manet’s widow, Suzanne, and presenting it to the French state. Monet’s plan worked, and today the painting hangs in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

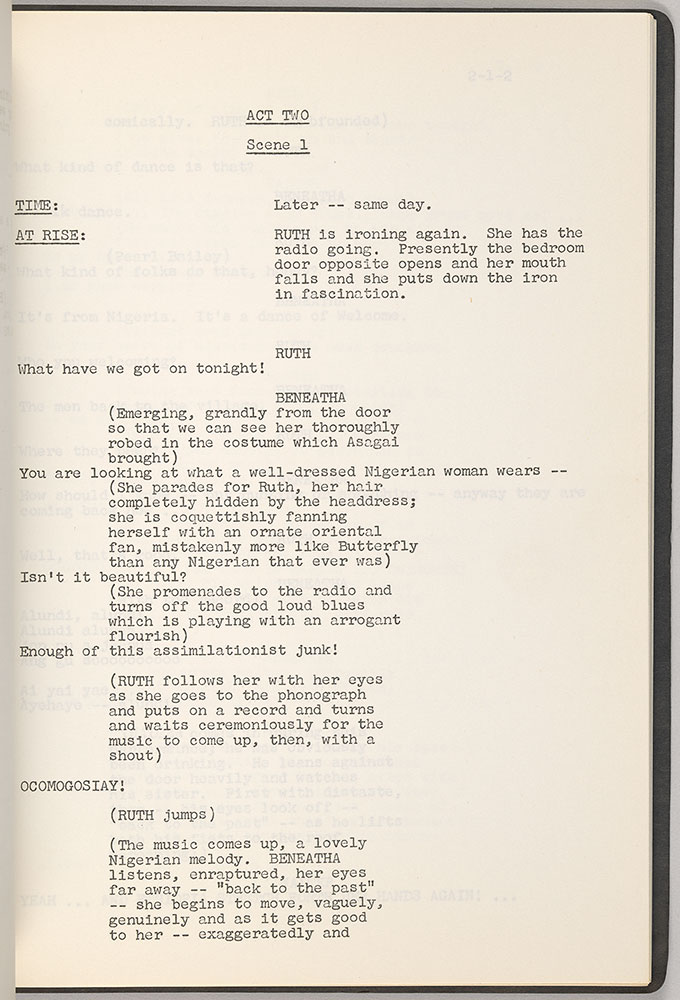

Ruth’s Time

Ruth Younger is the quietest character in Hansberry’s groundbreaking play, in which her commanding mother-in-law, Lena, and her volatile and despairing husband, Walter, get most of the lines. But at the end of act 2, scene 1, when she learns that Lena has bought a house in the suburbs for the family and that they can leave behind their cramped Chicago apartment, she at last gives voice to her feelings, as seen on this page.

In Ruby Dee’s performance as Ruth in the 1961 film adaptation of A Raisin in the Sun (a role she also initiated in the 1959 theatrical production), this moment marks a turning point: the stakes of the move, for Ruth, become clear.

All My Plays

Nethersole’s performance in the play Sapho, which she produced, directed, and starred in, was condemned by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice in 1900 for portraying a woman who shamelessly enjoys the prospect of sex. In this letter, dated several years before the production of Sapho, the English actor and producer refers to her newest hit, Carmen. She also mentions work on an upcoming play, writing, “I am in love with it but then that is no criterion because I am in love with all my plays.”

The Early Days of the Battery

Volta, for whom the electrical unit the volt is named, was an Italian physicist and chemist. When he wrote this letter to Barth, a Leipzig publisher and bookseller, Volta had just announced the results of his investigations into the sources of electricity. The “Appareil électrique nouveau” he refers to at the bottom of the first page is the voltaic pile, or the first electric battery. He also notes debates over electricity’s source and identity, referring to the work of his colleague Luigi Galvani, who had experimented with frogs’ legs and argued for the existence of “animal electricity.”

A French Composer in New York

In 1904, over her father’s objections and despite her equal talents in visual art, Tailleferre entered the Paris Conservatory, where she won praise for her prodigious memory and prizes as a pianist. She met the young composers Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, and Darius Milhaud in 1913, and in the 1920s, with Louis Durey and Francis Poulenc, they formed the group known as Les Six. Tailleferre was the only female member. In January 1927, during a stay in New York, she wrote this concertino for harp and orchestra and dedicated it to her first husband, the cartoonist Ralph Barton (1891–1931). Serge Koussevitzky directed the premiere in Boston on 3 March in the presence of Charlie Chaplin, who had attended every rehearsal.

Harry T. Burleigh’s Place

Burleigh, who popularized the Black spiritual “Deep River,” was deeply involved in the music and politics of his time, working with Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák, among others. Burleigh, a Black man, advised Dvořák on his efforts to bring Native American and African American influences into American classical music practice.

Burleigh and J. Pierpont Morgan knew each other. When Burleigh auditioned in 1894 as baritone soloist at St. George’s Episcopal Church, Morgan used his position there as chief warden to support Burleigh’s hire, over the objections of other White members. Burleigh sang there for fifty-two years. A span of East 16th Street, where the church still stands, was conamed Harry T. Burleigh Place in 2021.

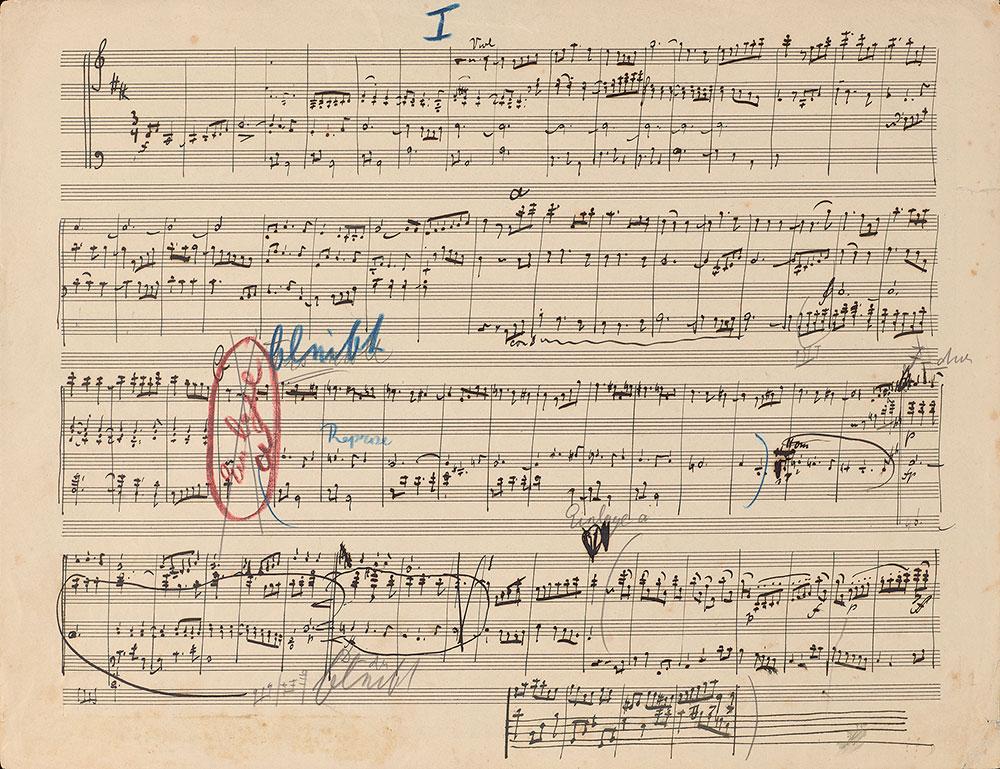

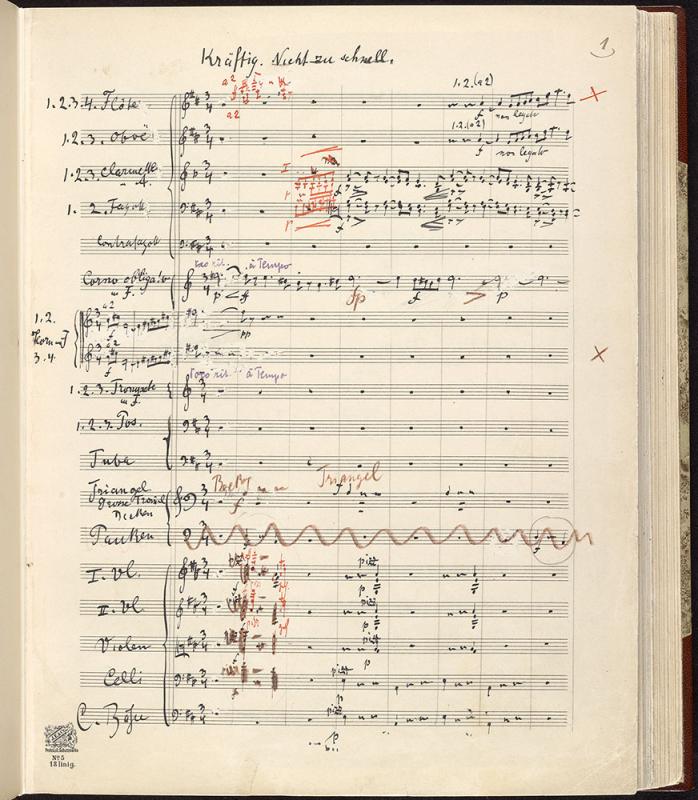

Worlds Engendered

In October 1904 Mahler led the premiere of his massive Fifth Symphony—a work featured in the film Tár (2022). The Scherzo’s opening French-horn call is shown here in a sketch (left) and in the final score (right). During rehearsals the composer had written to his wife, the composer Alma Schindler (1879–1964): “The public—Oh, heavens, what are they to make of this chaos of which new worlds are forever being engendered, only to crumble in ruin the moment after? What are they to say to this primeval music, this foaming, roaring, raging sea of sound, to these dancing stars, to these breath-taking, iridescent and flashing breakers?” The couple had recently married, in 1902, and the fourth movement, the Adagietto, is a love letter to her.

Gutenberg’s Side Hustle Indulgences were single-page documents sold by the Roman Church. In exchange for donating to a specific cause, a purchaser received a remission of specific sins. This indulgence, issued on vellum, helped fund the Christian kingdom of Cyprus’s crusade against the Ottomans, who had recently conquered Constantinople. According to the inscription, a man named Erasmus Damoder purchased it in Würzburg, Germany, on 13 April 1455, making this among the first printed fill-in-the-blank forms in the West. The larger print on the sheet is related to the type used in the Gutenberg Bible (also on display in the East Room), suggesting that Johann Gutenberg may have taken on this side job while creating his masterpiece.

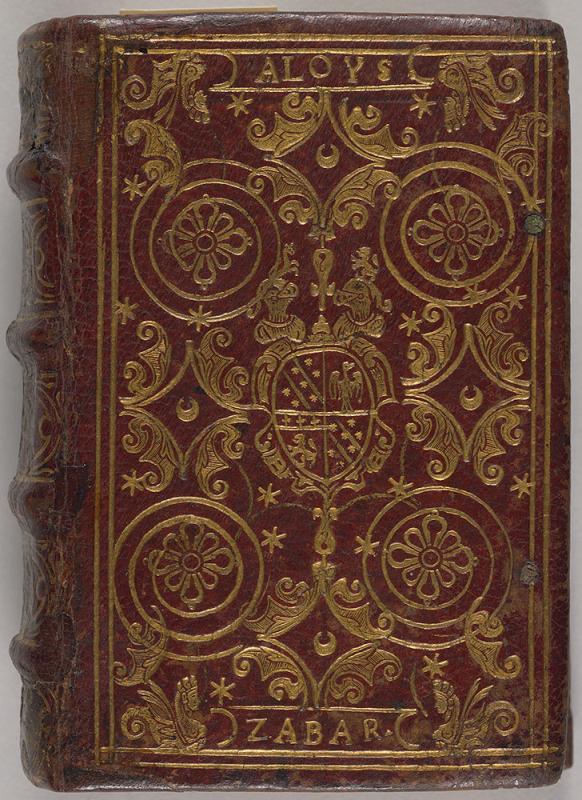

A Collector’s Love of Color

Julia Parker Wightman (1909–1994) was a bookbinder and noted collector of rare books. She began collecting in her twenties after a bookdealer suggested she might like to own a medieval Book of Hours. Over the next six decades, Wightman amassed a large library in her townhouse on Manhattan’s Upper East Side comprising illuminated manuscripts, rare volumes from the seventeenth through the twentieth centuries, fine bindings, miniature books, and early children’s publications and games. Wightman’s love of color informed her criteria for acquisitions, according to her friends, exemplified in her many goatskin bindings dyed in red, green, blue, or citron—virtually all, accented in gold. This red morocco specimen bears the arms and names of two powerful Renaissance families: the Zabarellas of Padua and the Cenci of Rome.

The Melancholy Mirror

Burton published his eccentric analysis of melancholy in 1621, and it remained popular throughout the century. Scholars have theorized that Burton experienced depression as a young man, a possible explanation for the nine years it took him to complete his bachelor’s degree. Establishing the definitive text of Anatomy was an even longer process. Burton made copious revisions to each subsequent edition, commissioning this illustrated title page in 1628. In his poetic “argument,” added four years later, Burton explains that the figures of melancholy—related to jealousy, love, superstition, loneliness, hypochondria, and mania—are mirrors of the reader, reflecting experiences we all share, to one degree or another.

Anamorphism Lightens Up

Anamorphic images feature the distortion and elongation of elements that can only be deciphered from specific vantage points. During the sixteenth century, painters embedded these kinds of images in their works, often to disguise controversial motifs related to magic, religion, death, and caricature. Later developments in anamorphism using curved mirrors coincided with the rise of the home entertainment industry in Europe. Shed of their former philosophical and scientific connotations by the nineteenth century, these “magic mirrors” became the basis for games for all ages. Can you see the dancer?

Image not available

Federico García Lorca (1898–1936), “Soneto a Carmela Cóndon agradeciéndole unas muñecas,” and cover of Les poétes du monde défendent le peuple espagñol, no. 3 ([Réanville, France: Nancy Cunard and Pablo Neruda, 1937]). The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; PML 185680

Poems to Combat Fascism in Spain The Chilean poet Pablo Neruda often asked Lorca to recite this early sonnet when they were alone. Soon after Lorca was murdered by Spanish Nationalists, Neruda and the poet Nancy Cunard handprinted the sonnet to raise money for anti-fascist forces in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39).

This copy was inscribed by Langston Hughes, whose poem “Song of Spain” is printed on the next page. Hughes, a supporter of the Spanish Republican cause, was one of many Black intellectuals to articulate the links between fascism and racism. Referring to the Spanish general in an article for the Baltimore newspaper the Afro American, Hughes wrote: “Give Franco a hood, and he would become a member of the Ku Klux Klan.”

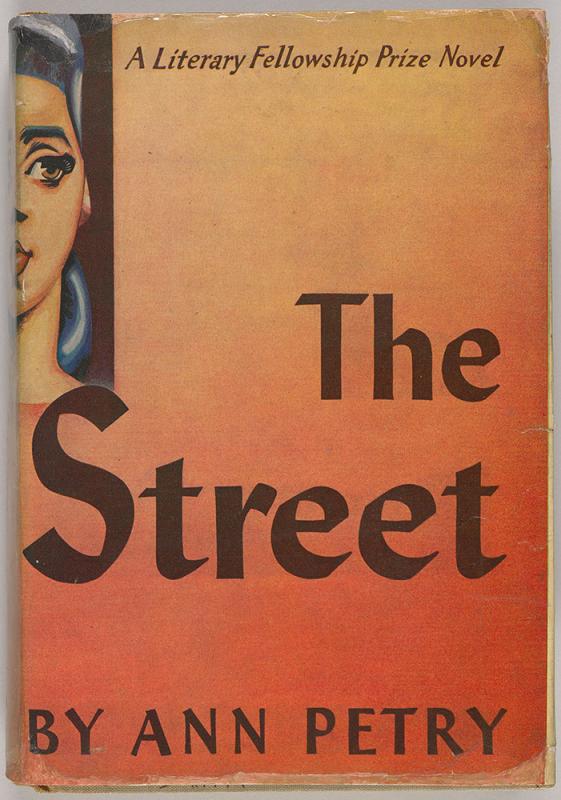

A Different Side of Harlem Petry’s The Street was the first novel by a Black American woman to sell over a million copies. Set in 1940s Harlem, with 116th Street as its backdrop, the narrative follows protagonist Lutie Johnson in her pursuit of financial security and dignity for herself and her eight-year-old son, Bub. Her best efforts are constantly thwarted, undermined by structural racism and misogyny.

Petry’s book broke from previous novels set in Harlem both in its depiction of everyday life and in the rawness with which it exposed the period’s rampant sexism. She inscribed this copy to Laura Z. Hobson, whose novel Gentleman’s Agreement garnered attention in 1947 for exposing the era’s antisemitism.

James Joyce (1882–1941), Ulysses (Paris: Shakespeare and Company, 1922). Gift of Sean and Mary Kelly, 2018; PML 197791

For One Week Only: Happy Bloomsday!

Written between 1914 and 1921, during the Irish author’s self-imposed exile in Trieste, Zurich, and Paris, Ulysses follows the young poet Stephen Dedalus and the unlikely hero Leopold Bloom, a cuckolded husband and figure of rare dignity, as they journey through Dublin on 16 June 1904—a date now celebrated each year as Bloomsday. Joyce, who was superstitious about numbers, chose to set his novel on 16 June 1904 because it was the date of his first rendezvous with Nora Barnacle, the woman who would become his companion for life.

To celebrate Bloomsday 2023, one of the many copies of Ulysses in the Sean and Mary Kelly Collection will be on view from 12 to 19 June. This one, copy no. 541, was inscribed by Joyce in 1924 to the American journalist David Karsner (1889–1941) and his wife, the artist Esther Eberson Karsner (1890–1982).

J. Pierpont Morgan's Library