Objects on view in J. Pierpont Morgan’s library reflect the past, present, and future of building collections in four curatorial departments, comprising illuminated manuscripts from the medieval and renaissance eras, five hundred years of printed books, correspondence and literary manuscripts, as well as printed music and autograph manuscripts by composers. These selections, which rotate three times a year, provide an opportunity for Morgan curators to spotlight individual items in different ways—to consider their historical and aesthetic contexts, and some of the stories behind these artifacts and their creators. Below are some of the highlights of the current rotation on view in the East Room and Rotunda.

Seven-Day Q&A

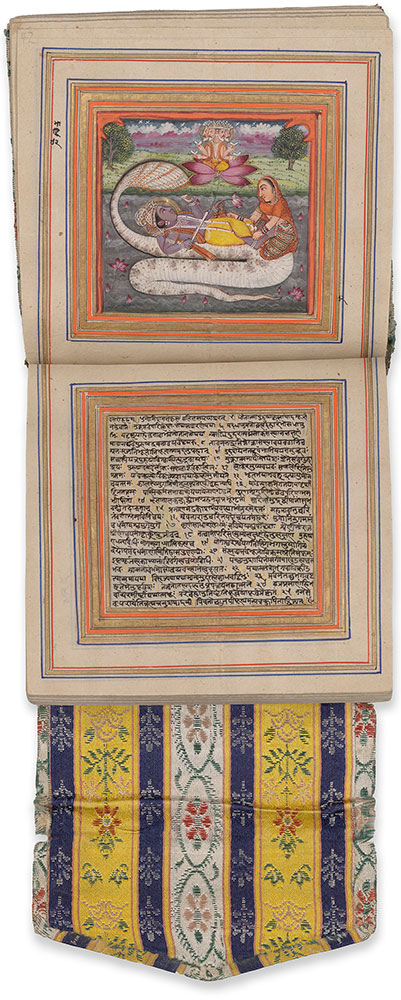

The Bhagavata Purana is one of eighteen Sanskrit compilations of legends about Hindu gods, sages, and heroes of ancient India. It is dedicated to the god Vishnu, whose histories are narrated in this book. The text is organized as a seven-day question-and-answer session between the sage Suka and King Parikshit about the history of the universe. Despite its small size, the manuscript here contains 137 miniatures and includes the entirety of the text, thanks to the tiny lettering and tightly packed lines of script. Here, the god Narayana (a form of Vishnu) reclines on the serpent Shesha as the goddess Lakshmi massages his feet. On top of the lotus, the four-headed god Brahma appears.

Mary Had a Little Lamb

Children have been singing Hale’s poem “Mary’s Lamb” for almost two centuries. A poet and novelist, Hale was among the first American women to edit magazines. She used her platforms to argue for equality in women’s education and to advocate for the moral and spiritual development of mothers and their children. Initially a religious hymn, “Mary’s Lamb” first appeared in 1830 in one of Hale’s magazines for children. It passed into popular culture through books and newspapers, quickly establishing itself as a mainstay in the new Sabbath Society schools (“Sunday schools”) throughout New England. One of its earliest musical settings is printed on this handkerchief, which was likely a prize bestowed on a Society student.

Speranza and O’Reilly: Two Irish Patriots

Lady Jane Wilde (1821–1896), Oscar Wilde’s mother, had a distinguished career as a poet, publishing under the pen name Speranza. She was particularly well known for her political verse advocating for Irish nationalism. In this letter, O’Reilly—a poet and nationalist who had been sent to an Australian penal colony for his revolutionary activities, and had made a bold escape to the United States in 1869—writes to praise her recent poems on Daniel O’Connell and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, even clipping out two lines from a printed copy of the latter poem to comment on them specifically.

A Couple’s Shared Love of Books

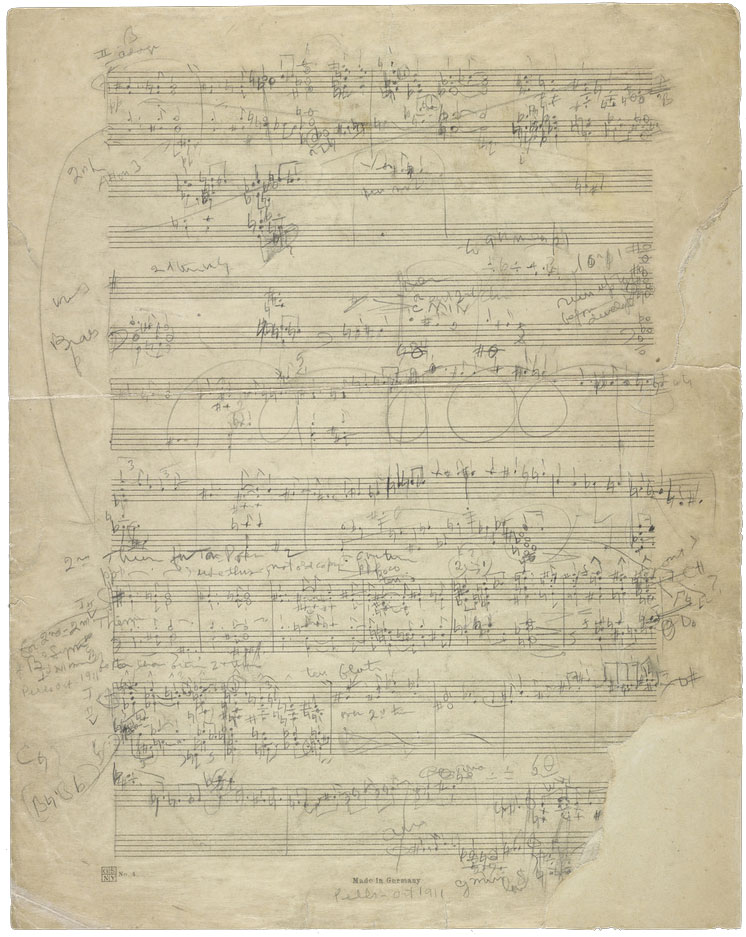

In a letter to her soon-to-be husband, the composer Charles Ives, Harmony Twitchell (1876–1969) expressed their shared love of literature: “We must plan to have times for leisure of thought & we must try & read a lot, the best books—we can live with the noblest people that have lived that way.” The couple often escaped their New York City apartment to Elk Lake, in the Adirondacks, where they spent long hours on the porch reading. During one of their visits there in October 1911, the composer sketched his Robert Browning Overture, the only completed tone poem of his intended “Men of Literature” series—inspired by Harmony’s gift to him, three years earlier, of a copy of Browning’s epic poem Paracelsus (1835).

Illustrating Colonialism

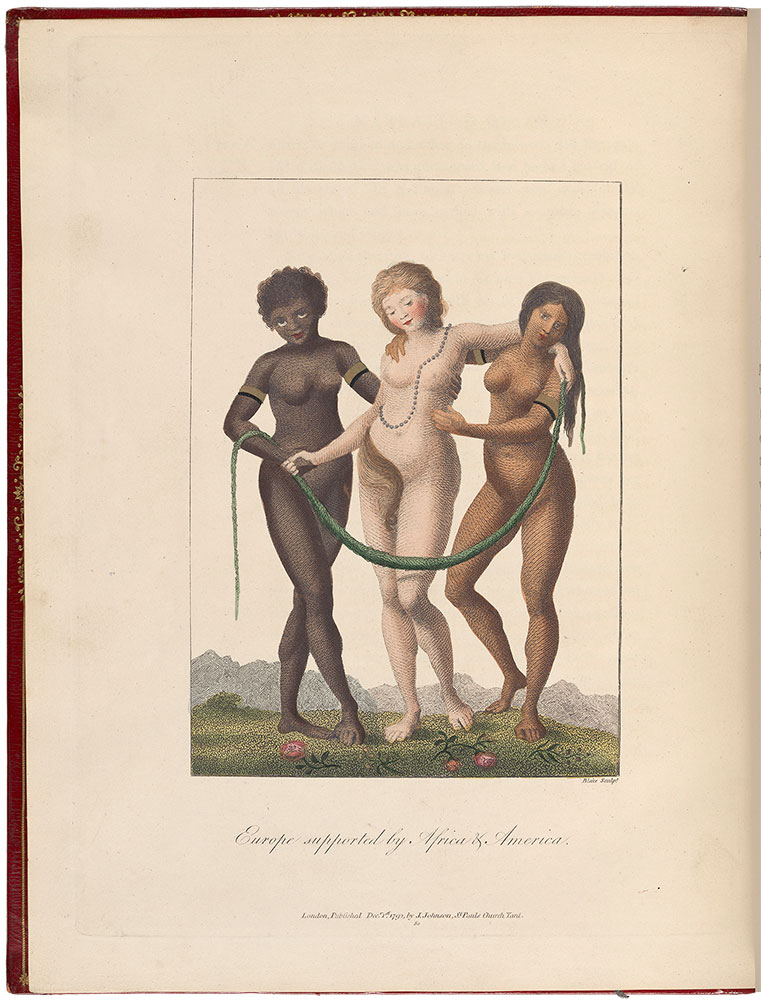

Dutch army officer Stedman’s belief that “we only differ in colour, but are certainly all created by the same Hand” was a compelling rationale for the transatlantic antislavery movements that took hold among late eighteenth-century liberals. Blake’s accompanying illustration, however, which was supposedly inspired by Stedman’s own drawing, lays bare the complexities of maintaining the “moral high ground.” In his anthropomorphic depiction of the continents—an allegorical tradition that long predates this image—Europe is being upheld by Africa and America, quietly suggesting how the wealth of European nations has been propped up by the global exploitation of colonized peoples.

Young Readers Take Control

This early children’s amusement is an example of a “metamorphoses book,” “harlequinade,” or “turn-up.” They are usually printed on one sheet of paper, sometimes hand-colored, and then folded into panels with cut-paper flaps. Readers can manipulate the illustrations and reshape the narrative by turning up and down the folds in different sequences. Early versions of the genre in the seventeenth century were didactic and religious in nature. In the 1770s, a London publisher capitalized on the popularity of commedia dell’arte and its stock character Harlequin by devising more lighthearted and colorful versions of turn-ups called harlequinades. For the next century, hundreds of playful editions were issued in Europe and North America.

Sappho’s Leap

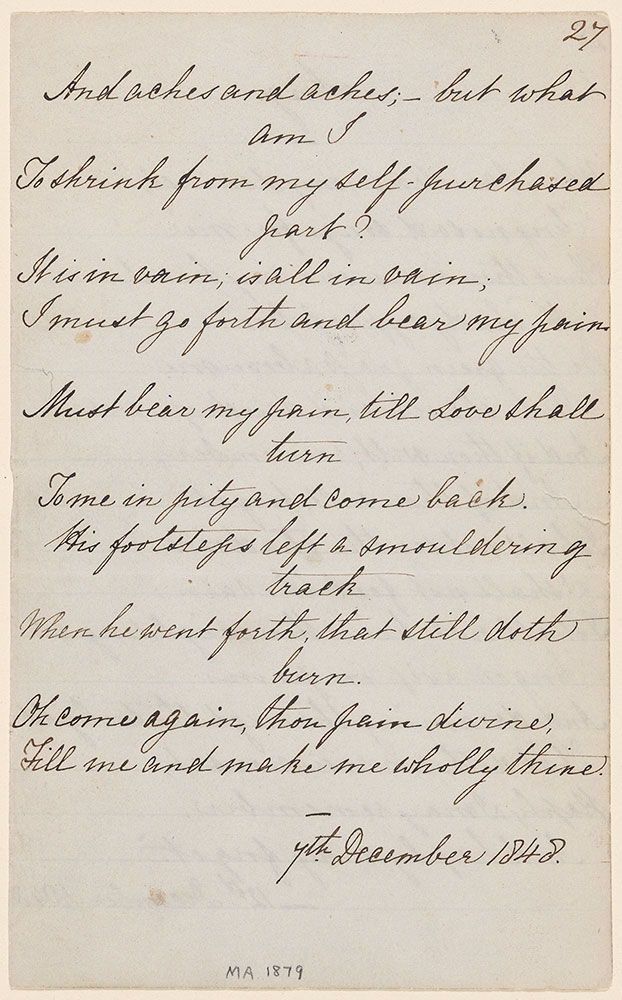

The other side of this leaf contains the original manuscript of one of Rossetti’s best-known poems, “When I am dead, my dearest.” On this side, however, are the final verses of a more obscure work in which Rossetti writes in the voice of the Greek poet Sappho. According to legend, Sappho leapt from a clifftop to cure herself of love. In Rossetti’s poem, Sappho’s leap leads not to death but to peace and solitude in a drowsy riverside idyll. And yet, the cure hasn’t quite taken: Love’s “footsteps left a smouldering track / When he went forth, that still doth burn.”

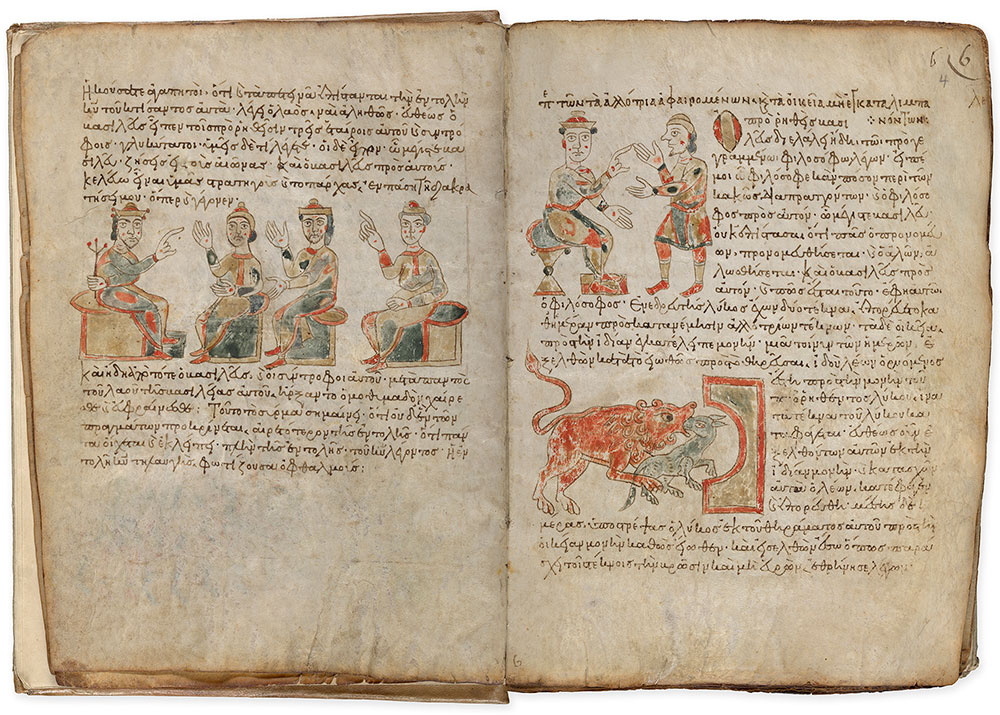

Mediterranean Connections

This manuscript contains several texts that were tremendously popular in the Middle Ages and beyond, including the Fables of Aesop. The opening on view shows two tales from the stories of the philosopher Bidpai, represented here at top right talking to a seated king. To the left is the end of the tale of “The Prince and His Three Companions,” and to the right is the beginning of “The Lion Eating a Wolf Cub.” Originally from India, these tales also circulated in Arabic translations, the likely source for this version in Greek. Written in southern Italy, employing a style likely influenced by Byzantine and Sasanian art, this manuscript shows how the Mediterranean has long been a region of active cultural exchange.

Jeweled Binding Made for Judith, Countess of Flanders

Judith’s father, Count Baldwin IV of Flanders, named her after Charles the Bald’s daughter, who married the first Count Baldwin. In 1051 she and her husband Tostig (the son of Godwin, brother of King Harold) went to England. Exiled in 1065 and widowed at age thirty-eight in 1066, in 1071 she married Welf IV of Bavaria, whose ancestral monastery was Weingarten. She died in 1094, leaving her books to Weingarten, where she was buried. The binding, possibly Germanic work combining delicate filigree and cast figures representing Christ in Majesty and the Crucifixion, was added in the last third of the eleventh century. The title on the cross, “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews,” is of translucent green enamel.

A Composer Getting by in Eighteenth-Century Europe

Haydn composed much of his early music for the private enjoyment of his sole employer, the Hungarian prince Esterházy. He wrote his Symphony no. 91, however, for public performance. Haydn dedicated the work to the comte d’Ogny (1757–1790), who had previously commissioned the composer’s six “Paris” symphonies (nos. 82–87) for the Concert de la Loge Olympique, a popular series supported by Freemasons. No longer restricted to composing solely for Prince Esterházy, Haydn— in a bit of double dealing—fulfilled two commissions with the same work, sending the autograph score to the comte and manuscript parts to a German patron, the prince of Oettingen-Wallerstein.

Fashionable Painting

This book of Gospel readings begins with a cycle of nine miniatures depicting events from the life of Christ, as well as images of the Virgin Mary. While their subject matter is traditional, their style was strikingly modern. Featuring heavy outlines, dramatic gestures, and clothing that seems to take on a life of its own, this new Zackenstil (zig-zag style) may have been developed by artists to animate their figures and enhance their expressive qualities. It swept through Central Europe in the early thirteenth century, permeating art and architecture. Shown here are the Annunciation to the Shepherds, at left, and the Adoration of the Magi.

Teasing Victor Hugo

Juliette Drouet, an actor, and the writer Victor Hugo were lovers and companions for nearly fifty years, though Hugo was married when they met and he went on to have numerous other affairs. Devoted to him, but rarely able to live with him, Drouet wrote over twenty thousand letters to Hugo. This letter gives a sense of Drouet’s wit, as well as of their loving but complex relationship. In it, she chides Hugo for bringing her “all those frightful newspapers” and tells him that that they will not distract her from his infidelity. It is just, she finally explains, that she wants “de vous voir et de vous avoir la plus possible” (to see you and have you as much as possible).

Democracy Restored, Sort of

Two years after their 1931 hit Broadway musical Of Thee I Sing, George and Ira Gershwin explored the career of its protagonist, US President John P. Wintergreen, in Let ’Em Eat Cake. In this darker sequel, Wintergreen loses reelection and asks the Supreme Court to overturn the results. When the court declines, the duly elected President John P. Tweedledee takes office. But Wintergreen and his vice president, Throttlebottom, propagate a revolution in the name of freedom, invoking the War of Independence. When the military takes their side, Wintergreen returns to office as a dictator. In the end, order of a slightly more democratic kind is restored after a baseball match between the Supreme Court and the League of Nations.

A Beloved Book of Songs

In 1790, at age fifteen, Gail published her first songs in two Paris magazines. An accomplished singer, she performed across Europe, and her salon drew fashionable Parisian musicians during the 1810s. During her brief life, Gail composed songs, romances, and several operas that were produced by the Opéra-Comique at the Théâtre Feydeau. Her music also was appreciated in England, where sometime in the 1820s Campbell, a young woman soon to marry the local reverend, lovingly copied out several of Gail’s songs in this book. Campbell used her graceful hand to further personalize the album with an exquisite frontispiece drawing, adding her signature to the design’s tiny music manuscript.

The Great American Novel

In this notebook, Loos, then a successful scriptwriter in Hollywood, composed part of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, the novel that would make her name and inspire numerous theatrical and film adaptations. The page on view contains an early version of the narrator Lorelei’s famous conclusion about the relative merits of chivalry and jewelry: “I really believe that American gentlemen are the best because kissing your hand gets you nowhere but a diamond and safire bracelet lasts forever.” Loos’s novel had many fans, including Edith Wharton. On a postcard, also on view, Wharton wrote to the editor of Harper’s Bazaar, where Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was serialized in 1925, pronouncing it “the Great American Novel.”

“Annotation Gives Your Book Back To You”

The Morgan holds two volumes of the Wolf Hall trilogy annotated by Hilary Mantel, which were auctioned to benefit the human rights organization English PEN. Mantel was eager to revisit her novels in this fashion, according to remarks quoted by the auction house, explaining that “annotation gives your book back to you” and restores “the sub-voce commentary that accompanies every session of work: ‘I could . . . but I won’t . . . and yet I could try.’” The Mirror & the Light, which concludes the trilogy, spans Thomas Cromwell’s final years (1536–40). Mantel’s marginalia in this copy provide insight into her characters and choices, illustrating her painstaking approach to creating fiction that is both artful and historically accurate. The page on view relates to what she rated as “probably the hardest decision in the trilogy”—how to approach the common belief that Thomas Cromwell had an illegitimate daughter, when the identity of the mother is unknown.

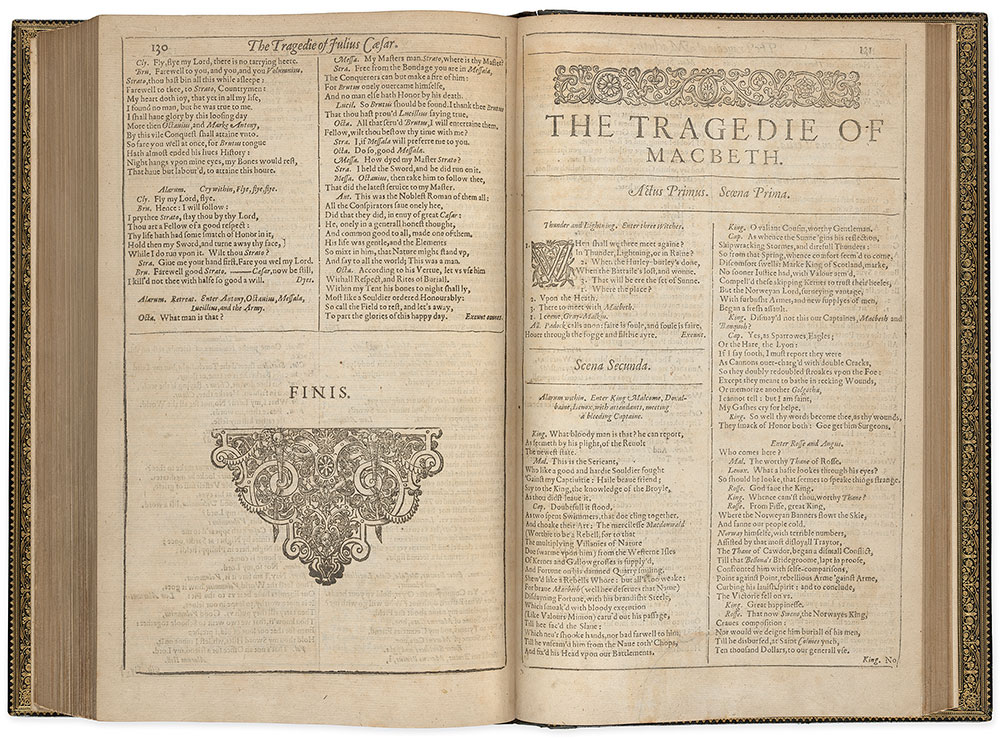

Four Hundred Years of Weird

Macbeth was first published posthumously in the (now) four-hundred-year-old volume of Shakespeare’s collected plays, referred to as the First Folio. Misogynistic fears of witches, prevalent in Scotland during the early modern era, are reflected in three female characters who foretell Macbeth’s fate. While the opening stage direction identifies them as witches, characters onstage call the trio the Weyward Sisters. Up until Shakespeare’s era, the term weyward (from the Old English wyrd, meaning “fate”) related to destiny; the modernization of English spelling, which replaced many i’s with y’s, and the sense of weird as something unusual or abnormal have encouraged editors and audiences today to call the characters the Weird Sisters.

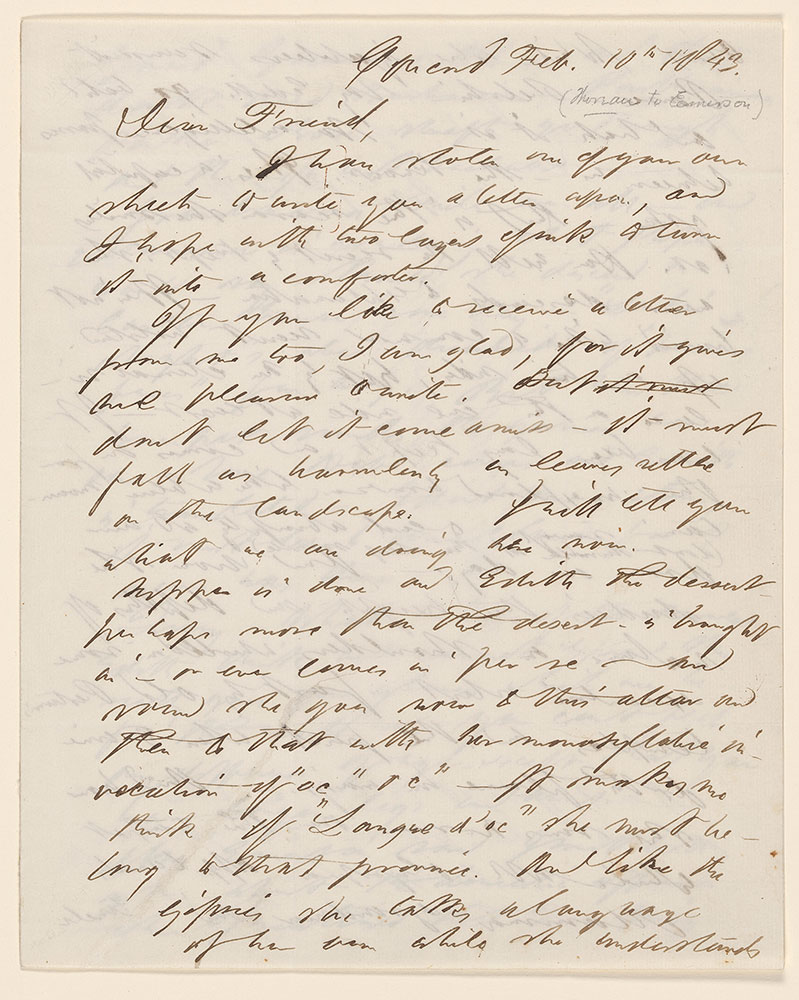

Thoreau Writes to Emerson

Dear Friend,

I have stolen one of your

own sheets to write you a letter upon, and

I hope, with two layers of ink, to

turn it into a comforter.

If you like to receive a letter

from me, too, I am glad, for it gives

me pleasure to write. But

don’t let it come amiss; it must

fall as harmlessly as leaves settle

on the landscape.

This intimate letter between American transcendentalist authors was written during Emerson’s first-ever trip away from his family, a visit to New York in 1843. Thoreau, who had been living with the Emersons in Massachusetts and tutoring their children since 1841, warmly recounts the domestic scene there, at the behest of Emerson’s wife, Lidian. Thoreau describes with particular charm the after-dinner behavior of the Emersons’ daughter Edith, who, at nearly fifteen months old, “studies the heights and depths of nature on shoulders whirled in some eccentric orbit.” Thoreau, writing a little over a year after the tragic death of his brother, John, seems content despite the sad anniversary: “I am well and happy in your house here in Concord.”

A Song for the Ages

This book’s parchment pages, metallic paint, and gold leaf evoke medieval manuscripts, but the volume is a modern creation by the artist Barbara Wolff. It contains both the Hebrew text and the English translation of the Song of Songs, a poetic dialogue between two lovers that is part of the Jewish Tanakh and the Christian Old Testament. Instead of featuring depictions of the lovers, each chapter of the Hebrew text begins with a metaphor for their love, written in gold ink. The full-page miniature that follows it to the left interprets that passage. Here, flowers floating against a skyscape evoke the scent of mandrakes filling the air. Grapevines illustrate other pages of text, along with flowers and precious spice boxes in the English section.

A Breakthrough in Black Women’s Writing

Printed in 1772, about twelve years after Jupiter Hammon became the first enslaved Black American man to publish a poem, Wheatley’s “Recollection” marks the first time verse by a Black woman writer appeared in a magazine. Her elegiac verse for the evangelist George Whitefield had been in circulation as both a broadside and pamphlet since 1770, but her first book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, would not be published until 1773 in London. The earlier version of “Recollection” in the London Magazine differs substantially from the one in her 1773 collection and is prefaced with her letter to the editors that gives the poem’s backstory.

J. Pierpont Morgan's Library