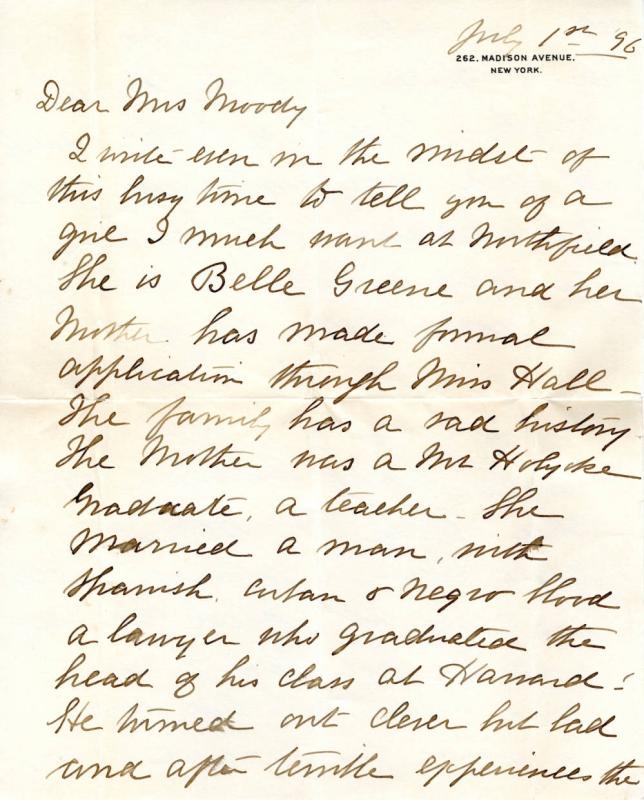

I recently came across a pair of letters that shed new light on the youth and education of the Morgan’s inaugural Director, Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950). On July 1, 1896, the philanthropist and social welfare advocate Grace Hoadley Dodge (1856–1914) wrote to Emma Charlotte Revell Moody (1843–1903), wife of Dwight Lyman Moody (1837–1899), an evangelist preacher and founder of Northfield Seminary for Young Ladies, in Massachusetts:

I write even in the midst of this busy time to tell you of a girl I much want at Northfield[.] She is Belle Greene and her Mother has made formal application through Miss Hall – The family has a sad history[.] The Mother was a Mt Holyoke Graduate, a teacher – She married a man, with Spanish Cuban + Negro blood a lawyer who graduated at the top of his class at Harvard: He turned out clever but bad and after terrible experiences she left him + has been supporting her five children with terrible struggle – Belle is bright, quick to learn, easily influenced[,] full of fun + energy – She has been employed as helper in the Office of Teachers College but we realize that she should go away from N.Y. and be under strong Christian influence – While the trace of Negro blood is noticeable Belle has always associated intimately with the best class of white girls + at the College was a great favorite with many[,] being entertained by them + going out with them – The Mother wants to make the girl a true noble woman + she has qualities for such if under such influence as Northfield – I will pay for her, and am most anxious that she be accepted – Is there any hope for her – The Mother, of course is white with good ancestry, and Belle inherits brains + ability – Trusting that the work is being abundantly blessed at dear Northfield + thanking you for all you will do for Belle

Grace H. Dodge to Mrs. Moody, 1 July 1896. Courtesy Northfield Mount Hermon Archives.

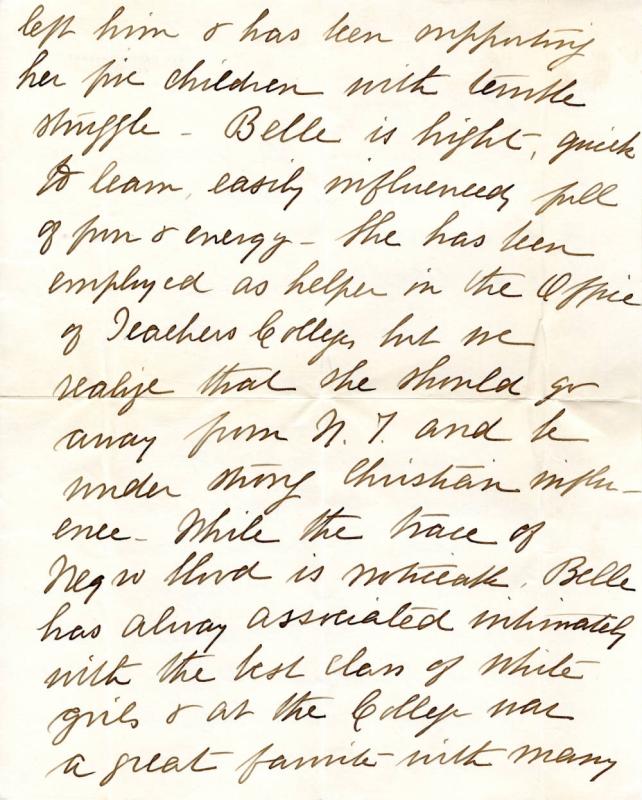

The following day, Emma Moody wrote to Evelyn Sarah Hall (1855–1911), Northfield’s Principal, relaying Dodge’s request:

I received a letter from Grace Dodge today which I enclose to you[.] I am sorry to send this to you in your rest but it is important + Mr Moody wants the girl received unless there is with you something very seriously against the girl that you may know of. Mr Moody wants to keep the Dodges in touch with the seminary as they have given much to the work here.

Emma C. Moody to Miss Hall, 2 July 1896. Courtesy Northfield Mount Hermon Archives.

These newly discovered documents have far-reaching implications.

Hall granted Moody’s request, and Greene attended Northfield for three years, although she left before graduating, as most girls at the time seem to have done. What Greene studied and with whom remains to be investigated, but the subjects she pursued and the network that she built there are sure to prove fascinating. The Dodge letter also reveals that before attending Northfield, Greene worked in “the office” of Teachers College, which she has often – erroneously – been thought to have attended.

The letters also shed important light on Belle Greene’s parents, particularly her mother, Genevieve Ida Fleet (1849–1941). Born in Washington D.C., to James H. Fleet and Hermione (née Peters), Fleet does not seem to have attended Mount Holyoke, as claimed in the first letter. Instead, like her future husband, Richard T. Greener (1844–1922), she attended Oberlin’s two-year college preparatory program in the 1860s, though she and Greener did not overlap there.

By the time these letters were written, Belle Greene’s parents had already separated. This was a full two years before President William McKinley appointed Greener to a consular post in Vladivostok, proving that his departure for Russia did not precipitate the family’s breakup, as previously thought.

As Grace Dodge’s letter also makes clear, by 1896 Greene’s mother had already changed her own last name, and that of her children, from Greener to Greene, and was actively passing as white. From then on, the Greenes identified themselves as being of Portuguese descent, with Belle adopting the middle name “da Costa,” her older brother Russell, “de Costa,” while Genevieve took a Dutch middle name, “van Vliet,” possibly because it sounded like her maiden name “Fleet.” All passed as white, a facet of Greene’s identity first uncovered by Jean Strouse, author of Morgan: American Financier.

What is perhaps most striking about the letters, however, is that Richard T. Greener’s identity, as both a lawyer and the first Black graduate of Harvard College in 1870 was known to Dodge. This was a part of the family’s mixed-race past that both Belle Greene and her mother actively sought to obfuscate in public records. Genevieve Greene is listed as a widow, for instance, in the 1900 census, and Belle Greene’s passport applications from the 1910s, list her father as deceased, although he lived until 1922.

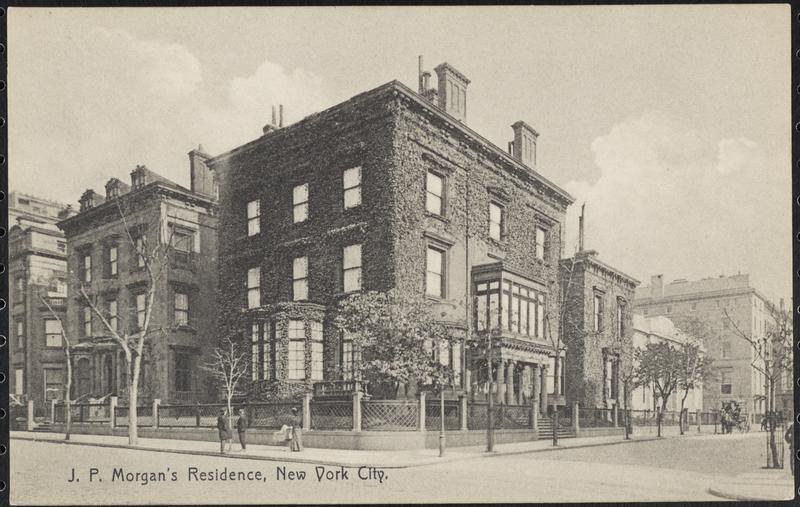

It is extremely suggestive that Grace Dodge was in possession of this knowledge. A trustee of Teachers College, where she and Belle Greene probably first crossed paths when the latter was employed there, Dodge was both a member of J. Pierpont Morgan’s social world and also his neighbor. As Dodge’s letterhead indicates, in 1896 she lived at 262 Madison Avenue, only a few blocks uptown from where the Morgan Library & Museum stands today. In fact, her grandparents had lived in the townhouse that originally stood at 225 Madison Avenue (the address of the Morgan today), immediately adjacent to Morgan’s own home. Neither townhouse now exists: in 1903, Morgan purchased the Dodge house, only to tear it down in order to create space for a garden, and his own house was demolished in the 1920s in order to construct the Annex Building (at the corner of Madison and Thirty-Sixth Street). Given their physical proximity and the fact that Dodge and Morgan traveled in the same close-knit social circles, it seems more than likely that Morgan himself was aware of Greene’s closely-guarded family history. That this, if true, does not seem to have affected his high regard for her, manifested in hiring her as his personal librarian and authorizing her to spend large sums to purchase items for his collection, suggests that he cared more for ability than ancestry.

In addition to revealing new biographical facts and giving us a deeper understanding of Belle Greene’s formative years, including the educational experiences that led to her career as one of the nation’s leading librarian-scholars, the letters have opened many new avenues of research that I am now pursuing1.

Daria Rose Foner

Research Associate to the Director

The Morgan Library & Museum

- I am grateful to Peter Weis, Archivist at Northfield, and Leslie Fields, Head of Archives and Special Collections at Mount Holyoke for their assistance. The latter confirmed that there is no record of Genevieve Ida Fleet having attended Mount Holyoke.