We asked some of the Morgan’s drawing and prints curators what their favorite portraits in the Morgan’s collections were, here are their answers.

Austėja Mackelaitė

Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator of Drawings and Prints

Dürer often turned to members of his immediate family as readily accessible models. In this study, he depicted his youngest brother Endres, who was active as a goldsmith in their native Nuremberg. Around thirty-two yers old at the time when Dürer made the sketch, Endres is portrayed wearing a beret cocked at a rakish angle, with his head turned sharply towards the left. This viewpoint emphasizes his bold features, such as the angular chin and close-set, slightly protruding eyes. I am particularly struck by Dürer’s ability to achieve a range of textures and visual effects—from the thick, fur-trimmed collar, to the reflection of light in Endres’s pupils—through the use of charcoal alone.

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528)

Portrait of the Artist's Brother Endres, ca. 1518

Charcoal on laid paper, background later washed with white lead.

Gift of Mrs. Alexander Perry Morgan in memory of Alexander Perry Morgan. 1973.17

In this double portrait, Van Dyck depicts Anna van Thielen, the wife of the Flemish painter Theodoor Rombouts, and their young daughter Anna Maria. The engaging study, which was certainly produced from life, exemplifies Van Dyck’s sharp powers of observation. With her eyes enlarged and eyebrows lifted just slightly, Anna confronts the viewer in a remarkably direct and forthright manner. Her daughter, in the meantime, appears to be gazing distractedly outside of the picture frame. Still, Anna Maria’s left hand rests gently on her mother’s shoulder, imbuing the image with familial warmth and comfort. While Van Thielen’s head and upper body are rendered with great care, with individual features accented using sharpened black chalk as well as pen and ink, the lower half of the image is just an energetic jumble of lines, showing the artist working very quickly to indicate the broad contours of his sitters’ dresses.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Study of Anna van Thielen and her Daughter Anna Maria Rombouts, ca. 1631–1632

Black chalk with pen and brown ink, on laid paper.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) in 1909. I, 244

Attributed to the eighteenth-century French painter and nobleman Joseph Ducreux, this gripping portrait might depict the abolitionist and writer Olaudah Equiano (ca. 1745–1797). Born in what today is southern Nigeria, Equiano was captured and enslaved as a child. He was first taken to the Caribbean and then to the English colony of Virginia, where he was purchased by Michael Henry Pascal, a lieutenant in the Royal Navy. After years of working mostly at sea, Equiano was able to buy his freedom, settling in London in 1766. The record of his life is preserved in an extraordinary autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; or, Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself, which appeared in 1789. The popular volume not only ran through nine English editions but was also published in the US, the Netherlands, Germany, and Russia. Ducreaux, who travelled to London at the outbreak of the French Revolution, might have met and portrayed Equiano there. Showing the sitter dressed in civilian clothes and turning towards the viewer, as if getting ready to speak, the work is similar to contemporary portrayals of writers and thinkers and resembles other portraits of Equiano known today.

Joseph Ducreux (1735–1802)

Portrait of a Gentleman, ca. 1802

Black, brown and white chalks on gray-blue laid paper.

Estate of Mrs. Vincent Astor. 2012.23

Laurel O. Peterson, Ph.D.

Moore Curatorial Fellow

During the fifteenth century, artists and patrons in Renaissance Italy were increasingly interested in individualized likenesses, in portraits that conveyed not only appearance but also personality and psychology. In this striking profile portrait, the artist has outlined the features of a monk, paying careful attention to his aquiline nose and short upper lip. With his bright eyes and the slightest of smiles, this monk seems like he might have had a good sense of humor.

Italian School, 15th century

Head of a Monk in Profile to the Left, ca. 1475-1500

Black and white chalk with smudging, on light brown paper cut to octagon shape.

Thaw Collection. 1976.43

We can debate whether we should consider this a portrait. The sitter, John Staveley is a known person, but the drawing was produced by Joseph Wright of Derby in preparation for a never-completed painting. Wright was illustrating a scene from Laurence Sterne’s novel Sentimental Journey (1768) in which an old man grieves over his deceased donkey. Wright, possibly attracted to Staveley as a model for his flowing beard and hair, renders him supported by a staff and wearing in a weighty coat. I love the way Staveley fills the large sheet of paper—his presence seems so large that he barely fits within the page.

Joseph Wright (1734–1797)

Portrait of John Stavely

Pen and black ink, over graphite, on laid paper.

Gift of Mr. Paul Mellon. 1976.20

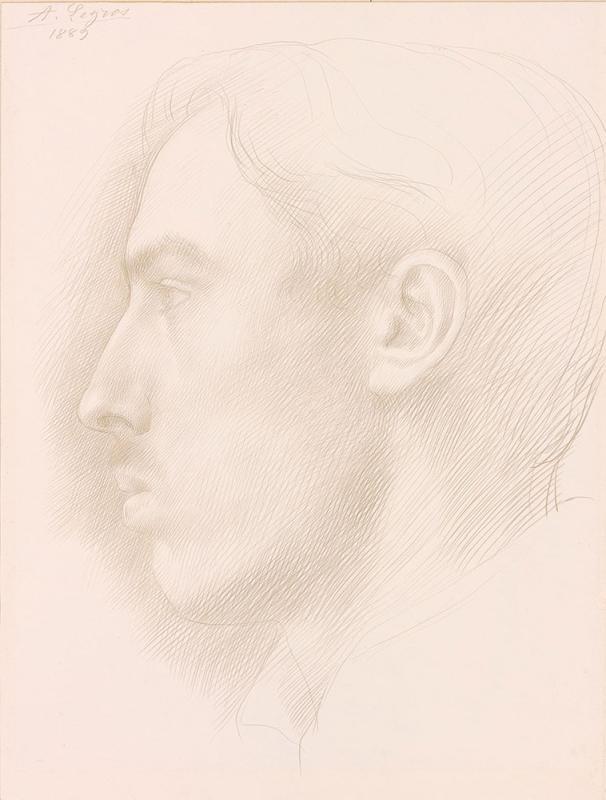

Alphonse Legros produced this sensitive profile portrait of his son, Lucien Alphonse, in metalpoint, a technique popular during the Renaissance that experienced a revival in the late nineteenth century. Legros modeled his son’s features with delicate hatching, suggesting a slight shadow across his face. Although the metalpoint technique and the use of profile are reminiscent of Renaissance portraiture, Lucien’s slightly tousled hair and the slight moustache point to the portrait’s modernity.

Alphonse Legros (1837–1911)

Portrait of the Artist's Son, L.A. Legros, 1889

Metalpoint on white prepared paper.

Gift of Paul Magriel on the occasion of his eightieth birthday, 12 March 1986. 1986.13

Jennifer Tonkovich

Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator

While the Morgan preserves some spectacular portraits from the Renaissance to the present day, I chose a few that were less well known and not meant to be virtuoso performances, but that have intrigued me over the years.

The Montgolfier brothers were responsible for inventing the hot air balloon, which they launched for the first time in 1783, This unusual double portrait by Boilly confronts the challenge of depicting the siblings together. I love that Joseph leans forwards with a smile while Etienne obeys the standard conventions of portraiture. Its almost like his brother crept in behind him as he was sitting for his portrait. Boilly had a terrific sense of humor and must have enjoyed cleverly sneaking Joseph into the frame.

Louis-Léopold Boilly (1761–1845)

The Montgolfier Brothers, Joseph-Michel (1740–1810) and Jacques Etienne (1745–1799), mid-1790s

Black chalk, heightened with white gouache on paper.

Gift of Stuart and Beverly Denenberg in honor of William M. Griswold, 2007. 2007.125

This self-portrait by Charles Fairfax Murray is so seductive. The portrait on the cover of a biography of this pre-Raphaelite artist, connoisseur, and art dealer is one of an older, dour-faced man with a long white beard. This study—made while he was young and ambitious—captures a certain boldness and daring that hints at his unorthodox career and lifestyle ahead. Pierpont Morgan bought his collection of drawings from Fairfax Murray, and so its particularly nice to put a face and a personality to that often told story.

Charles Fairfax Murray (1849–1919)

Self-Portrait

Brush and brown wash and pencil, some extraneous blue watercolor, on paper.

Purchased as the gift of Mrs. John Hay Whitney. 1996.151

I often think of this portrait, not because it is an excellent example of Ingres' draftsmanship, but because it shows him not having a great day. Although the artist is, in my mind, the most brilliant portraitist of his time, clearly he did not have the same affection for all of his sitters. This depiction of Lady Glenbervie, a Scottish tourist traveling through Italy in 1816, was executed sloppily, with quick, choppy lines. It lacks the elegance found in his portraits of colleagues and friends. Look at that silly bonnet! It is readily apparent that he was not fond of the sitter and was in fact tired of cranking out portraits of Grand Tourists for money when he wanted to focus on making ambitious history paintings.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867)

Lady Glenbervie, née Catherine Anne North. Verso: fragment showing a standing woman turned to the right. 1816

Pencil on wove paper.

Bequest of Mrs. Jacob M. Kaplan. 1998.19

Cezanne used this sketchbook during the 1870s and 80s in Paris and in his native Aix-en-Provence. Among the studies of landscapes and objects are a smattering of self-portraits and studies of his wife and friends. I find this particular page deeply moving. It shows the artist's boyhood friend Emile Zola, the acclaimed novelist (and one of my favorite authors), asleep. It is a reminder of the tremendous intimacy they shared, the power of their early friendship that lasted into adulthood. Cezanne sketched Zola on a visit before 1885, when these two brilliant artists would have a falling out over Zola's thinly veiled allusions to Cezanne in the author's novel The Masterpiece. They could never recapture the trust and love that is reflected in this quick sketch.

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

Sketchbook in use ca. 1875–1885

Graphite, with watercolor on one sheet, on 48 sheets of mixed white, blue, gray, beige, and brown wove paper, bound in beige linen.

Thaw Collection, Gift in Honor of the 75th Anniversary of the Morgan Library and the 50th Anniversary of the Association of Fellows. 1999.9