On December 21, 2021, the Department of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts received an exciting gift from Marguerite Steed Hoffman, member of the department’s Visiting Committee. It is a Book of Hours illuminated by an important fifteenth-century French artist—the Master of the Burgundian Prelates—whose work, prior to this donation, was not represented at the Morgan. This imaginative illuminator is named after a group of manuscripts commissioned by Church officials of the Burgundian towns of Langres, Dijon, and Autun. Active from around 1470 to 1490, the artist was most likely centered in one of those cities. Marguerite’s donation (now bearing the shelf mark of MS M.1200) not only filled a lacuna in the department’s holdings, it also provided us with the artist’s finest and most inspired creation.

John on Patmos, with the Destruction of Diana’s Temple and John turning Sticks and Stones into Gold and Jewels, Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. 14; Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

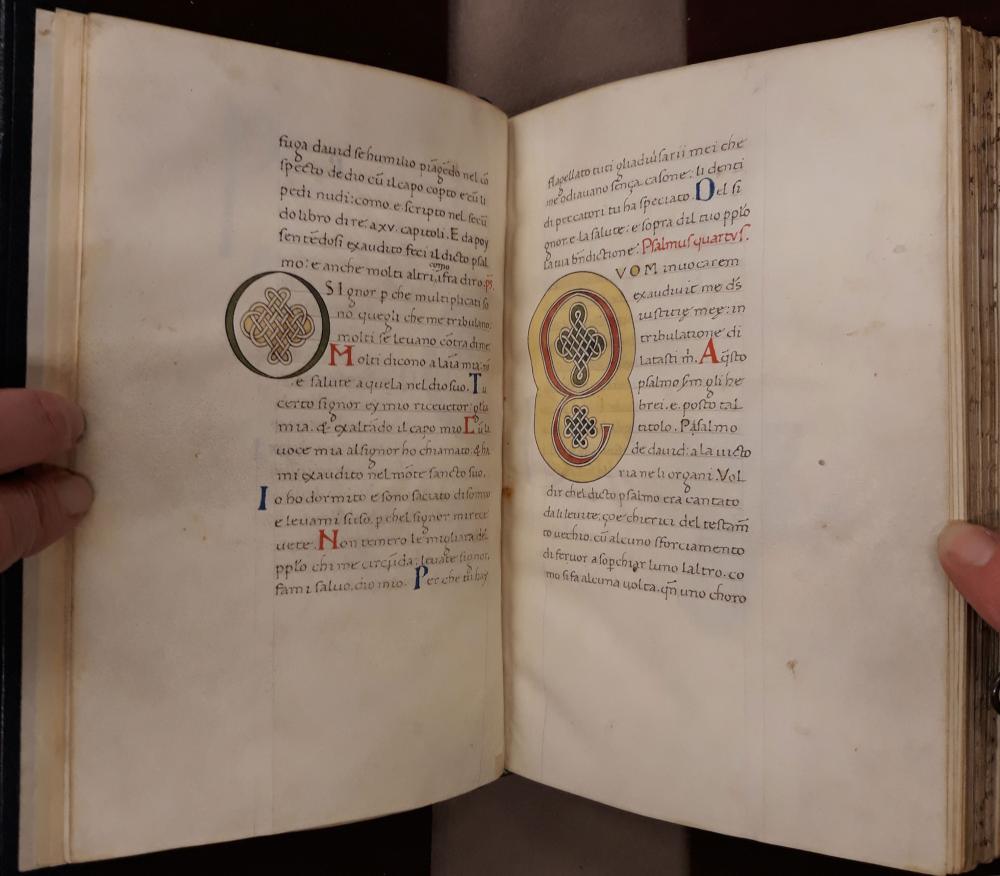

The book’s contents are traditional. They consist of a Calendar, Gospel Lessons, Hours of the Virgin, Hours of the Cross and of the Holy Spirit, Penitential Psalms and Litany, and Office of the Dead. The book’s fourteen full-page miniatures illustrating these standard texts, however, are anything but traditional. In both format and content, these paintings break with the norms of late- medieval manuscript illumination.

A typical page from a late medieval Horae with a large miniature, block of text, and four-part border. Annunciation, Book of Hours, France, Tours, ca. 1500–1515, illuminated by Jean Bourdichon (and others), MS M.291, fol. 14; Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913), 1907.

The layout of a page with a large miniature in a late-medieval Book of Hours typically positioned the image above a few lines of text and surrounded it with a four-part border, the varying dimensions of which increased from narrowest, next to the gutter, to widest, at the bottom of the page. These four borders might contain floral decoration or historiated scenes, but in either case, there was always, in a hierarchical manner, clear demarcation and distinction between the main miniature and the subsidiary border elements.

Visitation, with the Marriage of the Virgin and Gabriel Appearing to Joseph, Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. 33v; Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

In the present manuscript, the Burgundian Prelates Master literally sweeps this tradition off the page. Uniting the area traditionally occupied by the miniature with that of the four borders, he creates one large painting field that stretches from the top of the page to the bottom, from one side to the other. Few illuminators prior to this dared to be so revolutionary.

Crucifixion, with the Sacrifice of Isaac and Moses with the Brazen Serpent, Biblia pauperum (block book), Netherlands, ca. 1470, PML 19328, leaf.e. (det.); Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913), 1912.

The artist’s break with tradition was also iconographic. The artist must have had a copy of the Biblia pauperum in his workshop. This illustrated treatise presented the sequential events from the life of Christ, each juxtaposed with two prefigurations, that is, events, often from the Old Testament, that in theological terms were thought to foreshadow those of the New Testament. The artist added these typological prefigurations (or other ancillary vignettes) to nearly all of the fourteen full-page miniatures in this book, greatly enriching their narrative richness. While he could have owned a manuscript copy of the Biblia pauperum , the artist most likely had a block-book version of the sort that had been recently printed in the Netherlands, around 1470.

Crucifixion, with Sacrifice of Isaac and Moses and the Brazen Serpent, Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. 75v; Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

The miniature marking the start of the Hours of the Cross, for example, features, above the lines of the text, a large Crucifixion scene. To the left and below the text, two additional scenes can be spotted: the Sacrifice of Isaac, and Moses with the Brazen Serpent. The theological implications are twofold. Just as Abraham was willing to sacrifice his son, so God the Father willingly offered his son, Christ, for the salvation of humankind. Just as those who gazed upon the brass serpent that God commanded Moses to make as a relief for those Israelites who had been bitten by snakes, those who look to Christ will be granted salvation.

Annunciation, with the Temptation of Adam and Eve and Gideon with the Fleece, Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. 20; Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

The page that contains a large Annunciation in its top half has, in its lower area, the Temptation of Adam and Eve, and Gideon with the Fleece. Eve subjected humankind to evil and death by her disobedience to God; Mary reverses this by her obedience to God in accepting Gabriel’s message. Just as dew fell on Gideon’s fleece while the nearby earth remained dry, so the Virgin miraculously preserved her virginity during Christ’s conception.

Nativity, with Moses before the Burning Bush and the Flowering of Aaron’s Rod, Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. 48; Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

The page featuring the Nativity includes vignettes of Moses before the Burning Bush and of the Flowering of Aaron’s Rod. Just as the bush burned but was not consumed, so the Virgin’s body remained undefiled after giving birth to the Savior. Just as Aaron’s rod miraculously burst into flower, so the Virgin, untouched by man, brought forth the Savior.

David Decapitating Goliath, with David Fleeing Saul from Michol’s Window and Saul's Receiving David with the Head of Goliath, Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. 84; Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

If the events of the main miniatures in the Book of Hours did not occur in the Biblia pauperum , the Burgundian Prelates Master came up with other solutions to expand upon their themes. Thus, in what may be the book’s most dramatic composition, the page featuring David decapitating Goliath, the bottom also illustrates, at right, David Received by Saul following his triumph and, at left, David fleeing Saul out the window of the room where he was with his wife, Michol.

Annunciation to the Shepherds, Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. 53; Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

The Biblia pauperum also did not illustrate the Annunciation to the Shepherds. On that folio in the Book of Hours, the artist, with no typological vignettes at hand, painted a charming extension of his lush landscape, adding extra shepherds strolling about.

Procession of St. Gregory the Great, with the Three Living and Three Dead, Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. 99v; Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

Litanies in Books of Hours are hardly ever illustrated. In this rare exception to that rule, the artist has depicted the procession, which took place with litanies and chanted prayers, that Pope Gregory the Great led for three days in 590 when Rome was afflicted with plague. The church in the miniature alludes to Hadrian’s Mausoleum, upon which Archangel Michael appeared on the third day, sheathing his sword, a gesture that meant that God was appeased and the plague would cease. (The building was thereafter called the Castel Sant’Angelo.) The numerous casualties left by the plague are suggested by the motif of the Three Living and Three Dead at the bottom of the page.

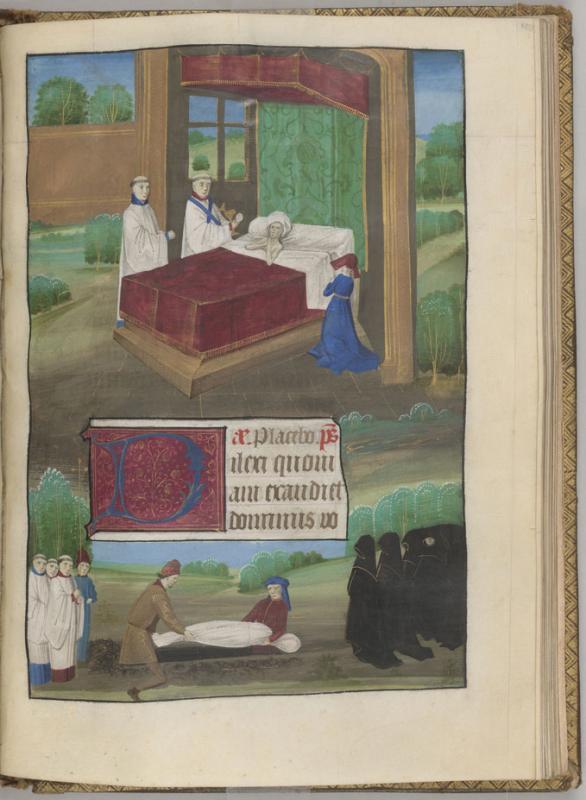

Dying Man Receiving His Last Communion, with a Burial, Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. 108; Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

In the book’s last miniature, marking the Office of the Dead, the main scene shows a dying man receiving his Last Communion—in medieval terms, the ideal death. The bottom of the page shows his burial, blessed by the priest.

Saint Claude on June 6 helps localize the manuscript to Burgundy. Month of June, Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. 7 (det); Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

As unusual as the book is in terms of page layout and iconography, it is equally rare in its rather full and illustrious provenance (ownership history). While we do not know the original fifteenth-century patron of the book, he or she probably lived in Burgundy (where the artist also lived). A handful of saints revered in that region of eastern France, such as St. Vincent of Besançon (in gold on 23 September), St. Lupus of Chalons–sur–Soâne (27 January), and St. Claude of Besançon (6 June), feature in the sparse calendar.

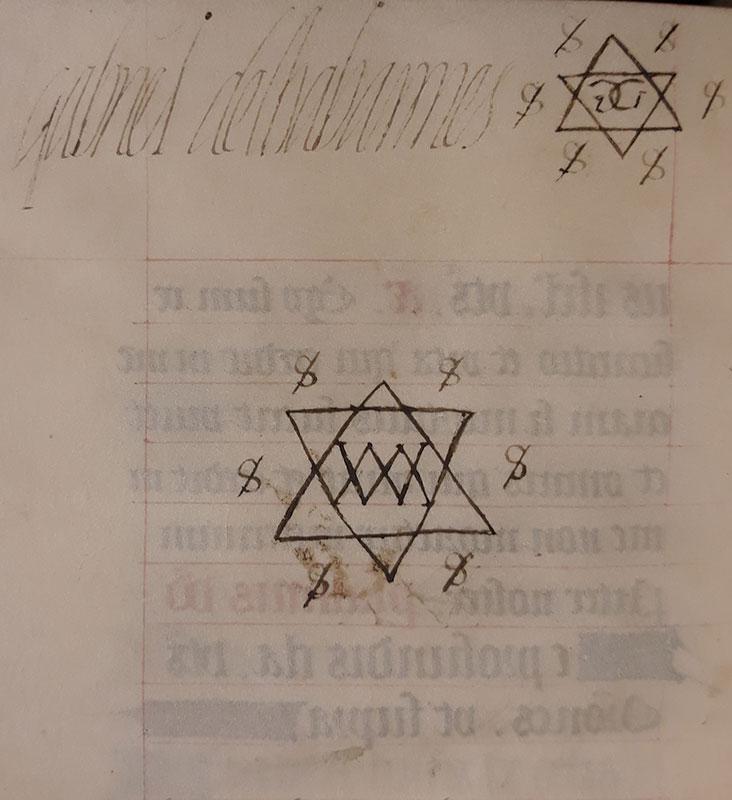

In the sixteenth century, the book belonged to Gabriel de Chabannes (1552–1599), vicomte de Savigny and seigneur de Chaumont. Records from the time call him a “gentilhomme de la chambre du roi” (gentleman of the king’s chamber), first “echanson de la reine” (cupbearer to the queen), and “chevalier de l’Ordre du Roi” (knight of the King’s Order). His name is inscribed on a final folio in a sixteenth-century hand—possibly his own.

Further inscriptions in Latin appear to be in a seventeenth-century hand. In the eighteenth century, the book was bound in French morocco and its spine stamped “Heure Gotique,” evidence that the book had remained in France for about 250 years after its creation. When it resurfaces in the nineteenth century, it is in New York City!

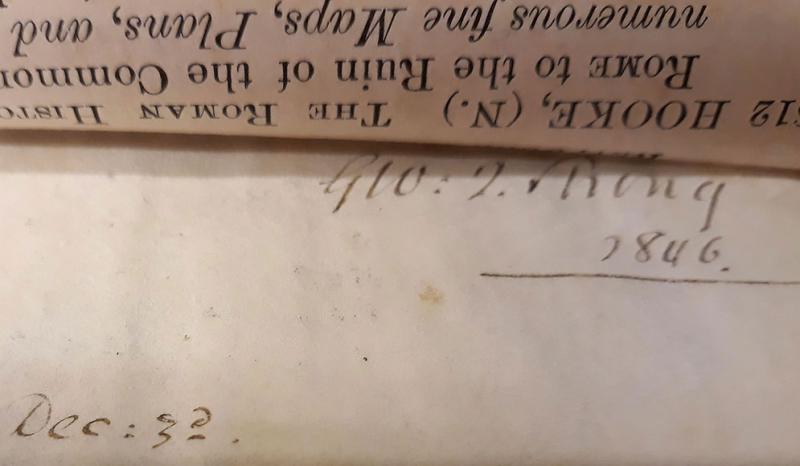

Inscription by George Templeton Strong: “Geo. T. Strong/Dec 3d 1846,” Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. i (det); Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

The next secure owned is George Templeton Strong (1820–1875). He inscribed his name and date of purchase on folio i: “Geo. T. Strong/Dec 3d 1846.”

A New York City lawyer, Strong is perhaps best known today for his 2,250-page diary, which he started in 1835, contributing entries for nearly every day for the rest of his forty years. (The published excerpts do not, alas, include an entry for 3 December 1846. A visit to the New York Historical Society, which owns the diary, is in order!) Of particular interest today are his entries during the years of the American Civil War (1861–1865). Ken Burns had selections from the diary read in his 1990 documentary, The Civil War . Strong was also a book collector. The sale of his library three years after his death (in New York, at Bangs & Co., in 1878) contained an amazing 1,763 lots. The auction catalogue’s introduction tells us, “The Missals, MSS., and early printed books are very valuable, and many of them exceedingly rare. It is altogether one of the best collections of books that has been in the market for many years.” The present manuscript was lot 820, one of fifteen manuscript Books of Hours and seven early printed ones. It fetched the highest price of this group, a not insignificant sum of $250 (the prices for the other twenty-one Horae range from $21 to $110). Among other medieval manuscripts, Strong also owned a Boethius, two Bibles, and four Psalters, one of which, a Neapolitan copy dated 1461 with most unusual decoration, is now our MS G.56, the second ex-Strong codex in the collection.

Description of lot 820 cut from the Strong auction catalogue inscribed by William Waldorf Astor: “Bought at the Strong Sale/N.Y., November 1878 $250.” Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, fol. i (det); Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

The buyer of lot 820 in the Strong sale was William (“Willy”) Waldorf Astor (1848–1919). He cut out the lot description from the auction catalogue, pasted it onto folio i (significantly, right over Strong’s name), and annotated it: “Bought at the Strong Sale/N.Y., November 1878 $250” (the sale price can be confirmed by the Morgan’s annotated copy of the Strong auction catalogue).

Willy Astor’s sticker: MS A.14. Book of Hours, France, Burgundy, 1480s, illuminated by the Master of the Burgundian Prelates, MS M.1200, front flyleaf (det); Gift of Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, 2021.

Astor also fixed a sticker with his manuscript number (MS A.14) onto the first flyleaf. Interestingly, Astor later acquired a second Book of Hours illuminated by the Burgundian Prelates Master, which became his MS A.18. After it was sold in 1987, that book was unfortunately broken up, its leaves now scattered.

Astor was an American-born lawyer, politician, businessman, and philanthropist. Scion of the extremely wealthy Astor family of New York City, he became the country’s richest man at the death of his father, John Jacob Astor III, in 1890. Moving to England the next year, Astor became a British subject in 1899. In 1916, in recognition of his many charitable works, he was made Baron Astor of Hever Castle. In 1917, he was elevated to the 1st Viscount Astor. He collected about two dozen illuminated manuscripts, a taste for which he may have acquired from his father, who donated a trove of manuscripts and early printed books to the Astor Library (founded by John’s grandfather and later merged into the New York Public Library). One of Willy Astor’s greatest manuscripts was the Great Hours of Galleazzo Maria Sforza, possession of which no doubt inspired his gothic romance, Sforza: A Story of Milan , published in 1889. When the Great Hours sold in 1988, it fetched $1.4 million, a record for an Italian manuscript.

The Hours illuminated by the Burgundian Prelates Master was inherited by Willy’s son Waldorf Astor, 2nd Viscount Astor (1879–1952), and then by his grandson William Waldorf Astor II, 3rd Viscount Astor (1907–1966). Shortly before the 3rd Viscount’s death, the book was placed on deposit at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, where it rested quietly for nearly a quarter of a century until its sale, by order of trustees of the Astor family, in London, in 1988.

Morgan Trustee and Visiting Committee member, Ladislaus (“Lazlo”) von Hoffmann (1927–2014), bought it, adding it to his fine collection of illuminated manuscripts. He later sold the book (part of his “Arcana Collection”) in London in 2011. At the 1988 Astor sale, von Hoffmann was also the buyer of the above-mentioned Great Hours of Galleazzo Maria Sforza, the Astor manuscript that set an auction record for an Italian manuscript.

At the sale of Lazlo von Hoffmann’s Arcana Collection in 2011, the dealer Heribert Tenschert was the buyer of the Hours illuminated by the Burgundian Prelates Master. He published it in his lavish two-volume Katalog LXXI, Tour de France: 32 Manuskripte aus den Regionen Frankreichs ohne Paris und die Normandie, 13. bis 16. Jahrhundert (“Tour de France”: 32 Manuscripts from French Regions outside Paris and Normandy, 13th to 16th Centuries), in 2013. The book then entered the collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman.

Roger S. Wieck

Melvin R. Seiden Curator and Department Head

The Morgan Library & Museum