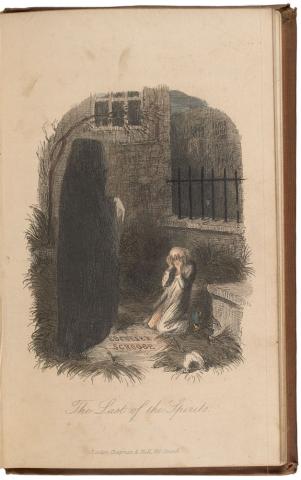

My first encounter with Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, in early childhood, was through film rather than text. I confess to having an inflated opinion of the 1970 musical version, with Albert Finney as Ebenezer Scrooge, and Sir Alec Guinness as Jacob Marley, directed by Ronald Neame. This was the first adaptation I ever saw and I was impressionable. A few years ago, I watched it again with my twin sons and noticed how disturbing one of them found the silent, hooded figure of the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. Just as it had profoundly affected me as a child.

My first encounter with Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, in early childhood, was through film rather than text. I confess to having an inflated opinion of the 1970 musical version, with Albert Finney as Ebenezer Scrooge, and Sir Alec Guinness as Jacob Marley, directed by Ronald Neame. This was the first adaptation I ever saw and I was impressionable. A few years ago, I watched it again with my twin sons and noticed how disturbing one of them found the silent, hooded figure of the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. Just as it had profoundly affected me as a child.

Although I had read a lot of Dickens’s work I was a latecomer to A Christmas Carol, reading it aloud each evening in the week leading up to Christmas, at the rate of one stave per night. I was nineteen years old and had no idea how important that teenage encounter with the text would prove to be, and how reading it aloud would later become something of a professional habit.

One of my earliest visits to the Morgan, after moving to New York from London, was to view the manuscript of A Christmas Carol and listen to an abridged reading by an actor in Mr. Morgan’s Library. That would have been in 1998. It seemed to me then—and still does now—to be one of the most enchanting ways to enter the Christmas spirit in preparation for the holidays.

When I joined the Morgan as a curator in May 2007, one of my first tasks was to select the page opening of Dickens’s manuscript. This decision is made in the summer because we plan months and, for our larger exhibitions, years ahead. Now, each year around the same time, I look again at the manuscript and decide which page to show. This year I chose the end of Stave One, which has always struck me as one of the most powerfully chilling passages of the book.

Another tradition that I look forward to each year is reading a passage from the story to the Morgan’s Young Fellows at their annual holiday party. I’d first suggested doing this as a lark in 2007 but it took root and I am honored to be asked back to this event each year to read to the assembled revelers in Mr. Morgan’s Library. It seems to have become a beloved Christmas tradition. Nowadays, I generally read the passage from the manuscript that is on view in the exhibition case.

This has been a particularly memorable year because on November 1 W. W. Norton & Company published a new facsimile of Dickens’s manuscript. This attractive, first-ever trade edition of the original manuscript has a brilliantly perceptive foreword by the novelist Colm Tóibín, and my introductory essay about the genesis of the story. It has been exciting to share one of the Morgan’s most important literary manuscripts with an even wider—and ever widening—audience. Last week NYC-Arts showcased the manuscript in their two-hour Christmas special and I was delighted to be asked to read short excerpts, and comment upon the story. The segment on A Christmas Carol appears in the first fifteen minutes of the show.

On Christmas Eve, BBC Radio 4 broadcast The Many Faces of Ebenezer Scrooge. In this program, cultural historian Sir Christopher Frayling explores how A Christmas Carol has endured in popular culture for over 170 years. I was interviewed about the manuscript in early November for this feature and am excited to join such luminaries as Claire Tomalin, Simon Callow, and Miriam Margolyes in talking about Dickens’s classic. This hour-long radio program is a must for all fans of A Christmas Carol.