On October 4th, 2019, John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal opened at the Morgan Library & Museum, showcasing heretofore underappreciated aspects of Sargent’s iconic oeuvre. Because he was known primarily as a painter of early-twentieth-century European and American, the public is most familiar with his highly-finished representations of the grand and great. However, Sargent largely ceased production of his portraits in oil by 1907, and from then on worked primarily in charcoal to fulfill commissions. As the curators note:

On October 4th, 2019, John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal opened at the Morgan Library & Museum, showcasing heretofore underappreciated aspects of Sargent’s iconic oeuvre. Because he was known primarily as a painter of early-twentieth-century European and American, the public is most familiar with his highly-finished representations of the grand and great. However, Sargent largely ceased production of his portraits in oil by 1907, and from then on worked primarily in charcoal to fulfill commissions. As the curators note:

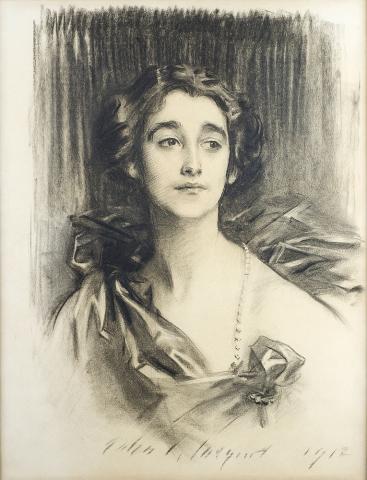

These drawn portraits represent a substantial, yet often overlooked, part of his practice, and they demonstrate the same sense of immediacy, psychological sensitivity, and mastery of chiaroscuro that animate Sargent’s sitters on canvas.

This exhibit is indeed an exploration of the often forgotten aspects of an artist’s portfolio, and it is noteworthy that one of its centerpieces—a drawing of Sybil Sassoon from 1912—is the bearer of another underappreciated story: that of the presence and impact of ethnic minorities in the upper echelons of early twentieth-century Britain.

Sybil Sassoon, later Sybil Cholmondeley, Marchioness of Cholmondeley (pronounced Chumley), was born in London in 1894, making her around eighteen years old when she first sat for Sargent. Within the year, she would be married to George, Earl of Rocksavage, later 5th Marquess of Cholmondeley, and would sit again, this time for a full oil portrait by the great artist as a wedding present from Sargent himself. Sybil and her brother Philip were scions of the Iraqi Sassoon family, a family of Mizrahi Jews who made their fortunes in British India and later migrated to London. The family story, typified by the lives and identities of Sybil and Philip, serves as an example of the societal dynamics of the time. That Philip was a patron and lover of the arts, commissioning works from figures such as his friend John Singer Sargent, demonstrates how minorities have been more central to what is a more complex and diverse art world than people may understand.

The Sassoons came to London in the nineteenth century and quickly began to climb the rungs of society, despite currents of anti-Semitism in British culture. Sassoon men studied at Eton and Oxford, and they served in the British military. Following the example of the Rothschild family (which they married into and followed into parliament), the Sassoons became well-ensconced in British high society. By becoming culturally assimilated, their difference was obscured.

Sybil and Philip’s mother was herself a Rothschild. It is interesting to note that the Sassoons first wed another Jewish (but European) family before intermarrying with the Christian nobility. We can construct a history of marriages stretching from the arrival of the Sassoons in England to Sybil’s marriage a generation later. In this history, we can see a process of shedding Arab-Jewish identity, which the family might have had before immigration, to exemplify ‘Englishness,’ as did Sybil and Philip. It is striking to think that Sybil, a British marchioness, had a father who was born in Bombay (present-day Mumbai) to parents from Baghdad. Sybil and Philip were the products of and actors in what was a dynamic, fraught, global patchwork of identity and exchange that existed due to the (often exploitive) interconnectedness of the British colonial world.

Sybil and Philip thrived. Philip, thought to have been a closeted gay man, became a member of parliament (the youngest at the time) and a patron of the arts. He was at the center of early twentieth-century British political and cultural worlds. Sybil became the financial savior and the mistress of a stately and historic British estate, Houghton Hall. These two bearers of marginalized identities contributed to the ongoing viability of white, patrician Britain. Sybil and Philip’s stories deserve to be known and honored.

Sargent’s charcoal drawings represent underappreciated works by a figure well-established in the Western canon of fine art. It is the initiative and insight of the Morgan curators that brought these beautiful pieces of art, as well as the story of Sargent’s process, to life. A full understanding of Sargent’s oeuvre would indeed be incomplete without an examination of his charcoal drawings. Furthermore, our appreciation and understanding of his career, as well as the artistic milieu of which he was a part, would also be incomplete without recognition of the influence and impact of oppressed group that were part of his work. The world of fine arts needs to recognize the presence of people of color, queer individuals and communities, and other minorities in shaping and promoting the works and careers of artistic greats.

When you visit the exhibition at the Morgan, remember the Sassoon siblings, not just their beauty and elegance, but the challenges they and their family experienced in order to be accepted. That they were themselves of the mega-wealthy class makes them seem distant and perhaps irrelevant; however, the history of their identities is a significant and accessible story in our diverse world. They are with us until January 12, 2020. Come while you can.

Yona Benjamin

Columbia University Class of 2020

Communications and Marketing Department Intern

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Sybil Sassoon 1912, charcoal. Private Collection, Photography by Christopher Calnan.