As a Canadian artist living in the US, I am both an outsider and a passive participant in our current political climate. I feel an urgency to address issues of class, power, and privilege through my work, while also treading carefully to avoid co-opting the experience of others. Instead, I approach my ideas through a tender provocation, asking myself how I can express a critical perspective that is nevertheless a positive and hopeful contribution.

Animals are complex surrogates in my work, as I navigate both my desire for connection to the animal world and an awareness of the power humankind exerts over our animal fellows. My portraits of animals offer an intimacy customarily reserved for human images and attempt to present these subjects with dignity, humor, and agency on a par with human portrait subjects.

This painting of Jesus was commissioned. The client had a detailed vision of the picture he had in mind, and we had a humorous working title: Hot White Jesus. To my mind, through that title, we were acknowledging the inherent historical hegemony of representing Jesus as white and were creating an image that also tipped its hat to Christ as an often unacknowledged erotic icon. Painting Jesus in a contemporary context felt both anachronistic and subversive, all the more so because of my client’s Christian faith, which was infused with his queer aesthetic and a genuine love of Jesus. Below is a brief selection from an interview I recorded with him (here called “D”):

D: I wanted to bring together these things that are very different, but that I love with the same intensity and fervor, that are seemingly discrepant, just to pack them all together because they all have the same source.

M: A handsome white Jesus holding a lamb is an iconic image, particularly in Christian pop culture, so we’re touching on that visual history in this painting. Our painting also reminds me that my interest in beautiful, sculptural, overbred animals is representative of a connection to nature—how we manipulate it, which is something I’m really interested in as a playful way to address issues of power and our relationship to the natural world. These kinds of fancy chickens are demonstrably a result of human intervention through breeding to, in a way, sculpt nature.

D: I think for me too—and this is one of the things I hold most dear about our life and something that is really deep for me in my spirituality—the sacred and the profane are two sides of a coin. To have this overwrought chicken and the exaggerated bow and the super‐dark colors and the light and fluffy content, it’s like good and bad, right and wrong, sexual and yet chaste, all at the same time. I feel like there’s no difference. I think the way into sexuality is chastity and the way into chastity is sexuality, and the way into depth is the surface and the way into surface, to really understand it, is to have a connection with the depth. So for me, anything I love has both sides of the coin to it. And I think that came through, on a subconscious level, in the portrait.

M: What you say reminds me that in my work I often combine the ridiculous with the serious, so it makes sense to me that you were interested in having me create a painting based on your vision, because your thoughts jibe with my aesthetic, which tries to get at serious content through absurd images.

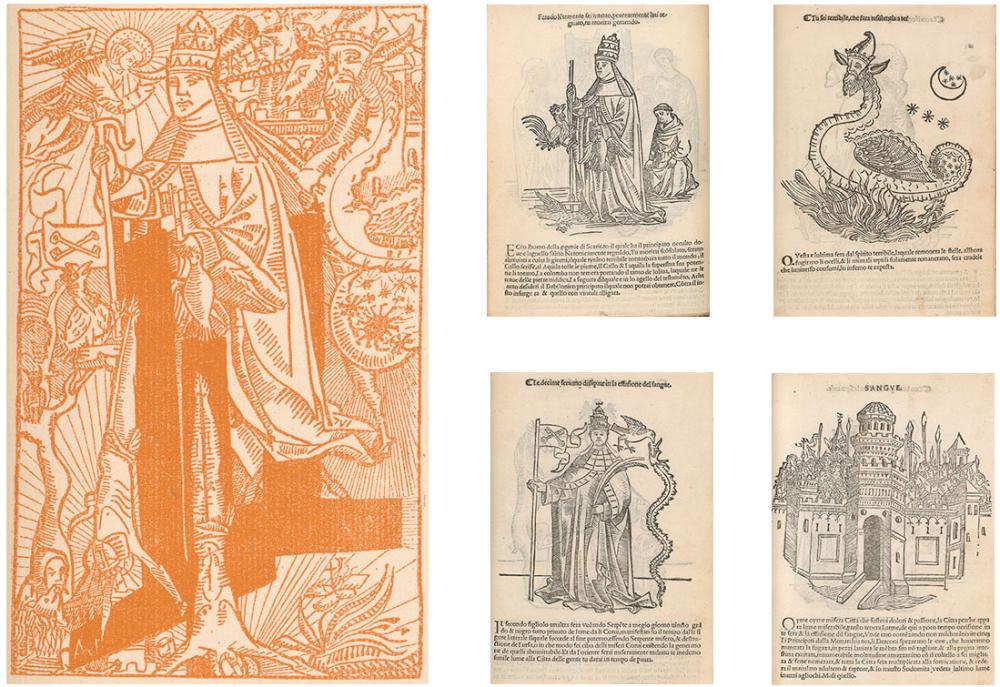

I thought Hot White Jesus paired nicely with the woodcut from the Morgan exhibition Alfred Jarry: The Carnival of Being, which also depicts a Christ-like figure and a rooster. I am delighted by his subversive character. Viewing the exhibition, along with a thought-provoking talk given by curator Sheelagh Bevan, inspired me to consider the modernist roots of appropriation and satire that are key to my own art practice.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

Source imagery, Prophetia dello abbate Joachino circa li Pontifici [et] R.E. (Venice: Niccolò & Domenico dal Gesù, 1527),The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1925. PML 23177.

I feel a particular kinship to this image from the exhibition, a wonderful example of the appropriation and recombination of anachronistic imagery in his oeuvre.

Considering Jarry’s radical vision, and this exhibition, is poignant for me as I aspire to explore issues of power and privilege through my work, in a global art culture that I experience as thoroughly institutionalized through academia and commercialized through the art market. I wonder, is it even possible today for an artist to have a subversive vision without complicity in the power structures of our current art culture, a complicity that blunts and renders mute any critical voice?

There are many objects in the Morgan’s collection that have a more obvious visual correlation to my paintings than Jarry’s works, as I often borrow from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century paintings, using them as settings for my animal portraits. In fact, I think of the readily available and endless landscape of pictures on the internet, whether it be historical artworks, pictures of Mr. Spock, or decorative chickens, in much the same way as Corot might have thought of the actual landscape outside his window. However, Jarry’s use of anachronistic imagery and appropriation, and his absurdist spirit in relationship to figures of power, remind me that the permission I feel to shamelessly steal images for my paintings has deep roots in modernist innovators like Alfred Jarry.

In my own painting, Louis I appropriated Hyacinthe Rigaud’s eighteenth-century portrait of Louis XIV, a painting that represents the height of European monarchic power. The royal figure is truncated, appearing only as a pair of stylish legs, with the king’s accoutrements of authority—his ample robes and bejeweled sword hilt—on obvious display. I have inserted a small dog, shifting the point of view by cropping the original painting, symbolically decapitating the king. Through this satirical work, I examine my own complicit relationship with a history of painting I both admire and recognize as a symbolic iteration of class privilege and colonial oppression. Our decadent past is filtered through the eyes of the absurd figure of a pampered poodle, itself a decorative object removed from its natural state and an avatar of our desires. In questioning, by way of reconsidering the past, our fraught present, I am striving to smuggle a sharp point beneath layers of painted silk and fur.

This second painting features a cropped copy of Louis XV (1710–1774) as a child, which itself is a copy of Rigaud's original portrait, with the attribution "after Hyacinthe Rigaud." I particularly like that my copy is itself a copy of an anonymous copy. I hope Jarry would approve! The handsome rooster portrayed is a Serama Bantam, one of the rarest breeds of chicken in the world. It is also the tiniest, growing to no more than six inches, and has an odd, vase-like shape and a prominent, proud breast. I thought such a diminutive yet absurdly dignified bird was perfect in a portrait of a five-year-old emperor. The Serama's colorful plumage also blends harmoniously with the palette of the original painting, as I aim to make my interventions in appropriated artworks as seamless as possible .

Circling back to the question I posed in response to Jarry, I genuinely don’t know if it's possible to express a subversive vision in today’s art culture. That said, generosity of spirit, love, and humor continue to ground me in connection to my fellows, both two- and four-legged, and I strive to bring those qualities to the paintings that I make.

Michael Caines

Conservation Assistant

The Morgan Library & Museum