Once the Pierpont Morgan Library’s newly-completed Annex building opened to the public in 1928, the library’s activities and staff expanded. The collection of prints and drawings could be consulted by scholars in the Reading Room, and works were routinely included in presentations in the main exhibition gallery. Initially, Director Belle da Costa Greene’s expertise was predominantly in manuscripts and printed books, so the collection of drawings was stewarded by staff members from those departments as an additional responsibility during the 1930s and first half of the 1940s (Figure 1). It wasn’t until 1945, when a curator was hired to explicitly oversee the collection that Drawings and Prints became its own department. The story of how that came about is also a story about the professional opportunities for women in museums following the Depression and until the close of the Second World War, and a story of specific personalities forging careers and adjusting to circumstances during these pivotal decades.

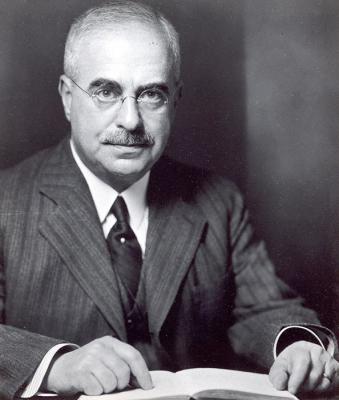

In 1934, Greene hired a talented and ambitious print specialist named Philip Hofer as part of the team responsible for printed books (Figure 2). Hofer was given responsibility for the prints, illustrated books, and drawings. He considered himself an assistant director at the end of his tenure, and referred to himself as such, given the large role he felt he played at the Morgan, though his title as listed in the library’s published reports remained curator of prints and illustrated books. Soon after Hofer started, according to an oral history he recounted fifty years later in 1984, he was at odds with Belle Greene. These two strong personalities apparently clashed, although we do not know how Greene viewed the experience. In his telling, he blamed her dislike of him on the fact that he realized—and let her know that he realized—aspects of her personal life that she had kept private.

…. Belle Greene decided very quickly that she didn't want me at all, because I knew too much. Not too much about books. I knew too much about her. I got to know pretty well about her, and guessed quite a few things about her. And she wanted me out. She didn't want to be succeeded, anyway by an assistant director.

He may be referring to his awareness that Greene, a Black woman born Belle Marion Greener who adopted the Portuguese-sounding middle name "da Costa," was passing as white, a facet of her life that Greene was forced to hide given the racist ideologies that underpinned the Jim Crow era.

Asked what role he played at the Morgan, he responded with a laugh:

I did what she told me to. I helped catalogue the drawing collection upstairs, and they had Rembrandt prints and things like that. I did what she told me to do. Sometimes she told me to go away.

After three undoubtedly tense years, Hofer resigned from his position at the Morgan in 1937. His passion as a bibliophile led him to found the department of Printing and Graphics at Harvard’s Widener Library the following year. Hofer focused on the history of illustrated books and remained as curator of the printing and graphics collection, which relocated to Houghton Library in 1942, until 1968. He was a particularly savvy and voracious collector of rare books and left his collections to the Houghton Library and the Fogg Art Museum. After Hofer’s departure, there was a need for someone to take responsibility for the collection of drawings and prints. William Ivins, curator of prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was made a consultant on the print collection in 1938. But drawings, stored alongside the prints on the top floor of the 1906 Library above Greene’s office, remained a collection without a curator.

In 1936, shortly before Hofer’s departure, Greene had hired Helen M. Franc to assist with the medieval manuscripts collection (Figure 3), working with curator Meta Harrsen. Franc also helped oversee the Reading Room where scholars would study rare materials from the collection. Franc was a graduate of Wellesley who received her Master’s degree from New York University in 1931. She had advanced to become a PhD candidate in medieval Italian painting at the Institute of Fine Arts by the time she started at the Morgan. An excellent wordsmith, she also deployed her editing skills on the Morgan’s annual reports. Eventually, towards the end of her six year tenure, she also took on responsibility for the drawings collection, a reassignment largely due to a clash with the head of her department.

Franc recalled her experience at the Morgan in an oral history taken in 1991. During her time at the Morgan, the drawings weren’t as high a priority as manuscripts, printed books, and prints and illustrated books, and therefore lacked a dedicated caretaker. The atmosphere at the Morgan during this period was characterized by strong personalities and some curious office politics:

I think I made the great salary of fifty dollars a week, which was quite fair in those days. I was sort of a special assistant to Belle Greene. I did all sorts of things, like showing visitors around, and then I did some work cataloguing the illuminated manuscripts. I worked on the annual reports and the press releases. I got to curate one exhibition, The Animal Kingdom, on which I had a great time.

But the atmosphere there was very strange. I think there were about nine professional people on the staff, of which there were three pairs of people who didn't speak to each other. That didn't mean six people, because some of the pairs overlapped. When I say they didn't speak, they didn't even pass the time of day. It was a very strange atmosphere. So Belle Greene at one point, sometime after I'd done that exhibition, removed me from the manuscripts because the person who was in charge of manuscripts was very jealous of me—she was many years my senior—and put me in charge of drawings, from which Philip Hofer had recently departed as curator. And I really didn't know anything about drawings, but I was just beginning on that when the war came.

As the United States entered the war after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, concern was high about the safety of the collection. It was feared that the East Coast, and New York in particular, might be bombed, especially the city with its active ports. Franc’s daily tasks soon focused almost exclusively on packing the collection to be stored offsite—the Rembrandt etchings went to Oberlin, and the drawings were sent to collector Lessing Rosenwald’s estate, Alverthorpe in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania (Figures 4, 5). Other parts of the collection were sent to Saratoga Springs and Whitemarsh Hall outside Philadelphia. Without a collection to care for, Franc lost interest and decided to leave. Well, here I was, a rather energetic young creature in my twenties, and not of a mind to sit out the war being the curator of a nonexistent collection. Franc went to work for the Office of War Information and then the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. After the war, she ultimately followed her mentor from Wellesley, Alfred Barr, to MoMA, where she had a long and celebrated career as editor.

With the departure of Franc in 1942, Mary Anne Farley was hired to assist with visitors, help with exhibitions, and lend a hand with the drawings collection (Figure 6). As significant portions of the Morgan’s holdings were sent to several secure locations, there was much logistical work to be done, as well as preparation and support for the library’s exhibitions. Farley was a native New Yorker living in Brooklyn who attended Hunter College and obtained her master’s degree from New York University. She had frequented the Morgan’s Reading Room in early 1939. Although researchers weren’t asked to note their topic at that time, she was certainly known to the staff after at least five visits. Farley’s focus, like Franc’s (and Greene’s) was medieval manuscript illumination and she had spent six months in Paris on a Fulbright scholarship before returning to New York. An essential member of Greene’s small staff, Farley’s salary was raised to $175 a month in May 1944. Her tenure ended in 1945 when she married Edward Tully, a captain in the merchant marine. Within a few years, Farley relocated with her family to Princeton, working at the Index of Christian Art and for professor Millard Meiss. Farley also served as a trusted translator for Charles de Tolnay in his writings on Michelangelo.

Farley was at the Morgan as the collection returned from offsite storage in shipments from December 1943 until May 1944. Although the drawings were back onsite, following Farley’s departure they lacked a designated caretaker. At last the library decided to officially establish drawings and prints as its own department. Other museums had already hired drawings-specific curators, such as Harvard’s Fogg Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago. Now the Morgan’s Board of Trustees and Greene needed to find the right person to head the library’s department.

They would choose Felice Stampfle, who began in 1945 and led the department until her retirement in 1981. Stampfle was a Midwesterner raised in Kansas City, Missouri, who earned her bachelors and master’s degrees at Washington University in St. Louis (Figure 7). Stampfle later recalled the advice she received on how to enter the curatorial field: One of the places I interviewed in Kansas City, my own city, after I had a masters, the man said...the best thing you can do is take a secretarial course and enter that way. Stampfle rejected that path and instead applied to pursue graduate work at Radcliffe.

In 1943, Stampfle enrolled in Paul Sachs’s Harvard course “Museum Work and Museum Problems.” In his course, which he taught from 1921 until 1948, Sachs trained a generation of connoisseurs in a range of fields (Figure 8). During Sach’s course, she was strongly influenced by Jakob Rosenberg, curator of graphic arts at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and a professor of art history at Harvard (Figure 9). Rosenberg was friendly and accessible, and she also preferred his calm, analytical approach to the more irascible, and emotional, Sachs. Rosenberg’s focus was largely on drawings, with a specialty in Northern artists such as Rembrandt and Rubens. Inspired, Stampfle also chose Northern Renaissance and Baroque drawings as her field of specialization.

One important aspect in discussing women’s advancement in the curatorial field is the economics of graduate degrees and museum work. Stampfle arrived in Cambridge with a clear ambition but without funding to sustain her during graduate studies. In order to support herself, she quickly gained employment as a social secretary and au pair to Paul Sachs’s daughter Elisabeth, who was recently widowed. Not long after she began his course, Paul Sachs awarded her a Fogg Fellowship, which provided financial support (Figure 10). He also became her staunchest supporter, even though Stampfle had a falling out with his daughter. As she recalled, I admired Sr. Sachs tremendously. He didn't hold it against me that his daughter and I didn't get along.

At the Morgan, according to Stampfle, The board of trustees informed Sachs that they were looking, this time, for a third "Miss Mongan,” meaning the talented sisters whom Sachs had trained. Agnes Mongan had been in charge of drawings at the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard since 1937 (Figure 11), and her sister Elizabeth was curator for the collector Lessing Rosenwald, and later accompanied his collection to the National Gallery where she served as curator of prints. As a 1978 Washington Post article referring to Agnes noted, “In a field ruled for years by men, many wealthy or high-born, Mongan, who is neither, nonetheless attained much in her profession. So did her equally well-known sister, Betty.” The same can be said of Stampfle. Did the Morgan’s board and director, after the experience with Hofer, see the model of the Mongan sisters—both of whom were respected leaders in their field—as the template for success at the library? Stampfle’s take on her hiring was simply, "I was there at a time when it was to the advantage of women as many men were not.. .due to war."

But it wasn’t simply the dearth of men during the war that led to Stampfle being hired (Figure 12). Sachs wrote to Greene in 1944 recommending the thirty-two year old Stampfle over other students who had applied for the position:

Miss Felice Stampfle is a candidate for a position at the Morgan Library. I hope it will be possible for her to secure this position for she is one of the best of our graduate students....[She] was a member of my Museum Course seminar and did excellent work...I found her to be a serious, conscientious, and a first rate student.... She was awarded one of our best fellowships for this year.

I feel sure that if she should join your organization you would find her cooperative and able to do an A-l job.

I can only think that in addition to her maturity and training, Stampfle’s seriousness, focus, and directness must have appealed to Greene after the sparring of egos that took place with Hofer. Stampfle would be the sole person in charge of drawings, and the first one for whom drawings were the focus of her scholarly work. The independence of the position would allow Stampfle to avoid clashing with any superiors, as Franc did with Harrsen. The Morgan had its “third Mongan sister,” (though Stampfle no doubt would have disdained that moniker) who would maintain the Morgan’s high standards for the next thirty-eight years.

To further explore sources quoted in this post, see:

- Philip Hofer’s oral history.

- Helen Franc’s oral history.

- Felice Stampfle’s recollections: Sally Anne Duncan, Paul Sachs and the Institutionalization of Museum Culture between the World Wars, Ph.D. dissertation, Tufts University, 2001.

Jennifer Tonkovich

Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator

The Morgan Library & Museum