The mid-eighteenth century witnessed the flourishing of scientific illustration in Europe. In an intellectual climate that valued curiosity and experimentation, the goals of the artist frequently merged with those of the scientist. Before the invention of photography, artists needed to document botanical specimens quickly before they decayed. These visual records of plants aided in their identification and classification and also functioned as aesthetically pleasing works of art. This intersection of art and science provided a place for women artists, who sometimes struggled to find patrons in the more traditional genres of painting. Madeleine Françoise Basseporte (1701–1780) was one of the highest ranking botanical artists in France. She was the first woman to hold the position of official painter of Louis XV’s garden, a post which she retained until her death.

My curiosity about Basseporte was piqued when I began looking at drawings by women artists in the collection as part of an effort to improve our cataloguing records. As it turns out, the Morgan preserves several boxes of her botanical illustrations. A cache of 117 watercolors on vellum entered the collection in 1952 as a gift of Junius and Henry Morgan. They were bound in an album that had belonged to their mother, Mrs. J. P. Morgan, Jr. (1868–1925), known familiarly as Jessie Morgan, an avid collector of volumes of prints and drawings connected to garden history. At that time, the drawings were attributed to an artist in the circle of the renowned flower painter Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759–1840). On a visit to the Morgan in 1963, however, Gabrielle Duprat (1898–1999), curator of the Bibliothèque du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris, identified the drawings as the work of Basseporte and her pupils.

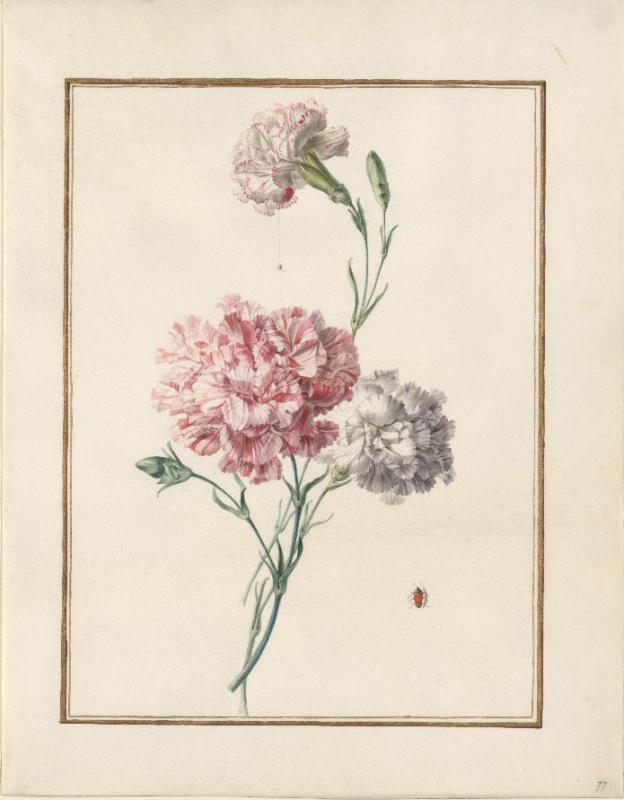

As part of her role as official painter of the King’s garden, Basseporte was obliged to contribute to Les Vélins du Roi (The King’s Vellums), a codex of plant and animal illustrations started in 1631 to document specimens from the royal collection. Comparison of the Morgan’s watercolors with the majority of the vellums, which are housed in Paris’s Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, strengthens the argument for her authorship of the Morgan’s sheets. Additionally, an album of flower drawings in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF, département Estampes et photographie, RESERVE JD- 33 -PET FOL), fully accepted as the work of Basseporte, provides a close comparison to the Morgan’s drawings. Both sets of vellums typically represent two varieties of flowers on each page, often enlivened with insects. The specimens are seen against a blank background and feature double borders in red ink and gold leaf. Some of the Paris drawings also contain inscriptions identifying the flower species in graphite, in the same hand that is found on the Morgan sheets. However, neither are signed or dated, but it was not uncommon in the eighteenth century, especially for women artists, to leave work unsigned.

The Morgan drawings are exceptional for the freshness of the watercolor, thanks to the works being bound into a volume and protected from light for nearly two centuries. On closer inspection of the Morgan’s drawings, it became clear that the sheets had been bound more than once over the years. The margins between the decorative border and the left edge of the leaf, proximal to the spine, were roughly one and a half centimeters narrower than the margins between the border and the right edge of the sheet. The reverse of the page along the left edge also contained traces of an old adhesive. This physical evidence indicates that the sheets were bound more than once: at some point they were cut from one album (resulting in the unequal margins) and rebound into another album with stubs (adhered with glue). This speaks to the desirable nature of the drawings and the longstanding practice of assembling them into albums for storage and enjoyment.

But if the Morgan’s sheets are by Basseporte, when and where did she make them? One compelling possibility arises. On multiple occasions, Basseporte also worked for the King’s official mistress, Madame de Pompadour, who invited Basseporte to depict flowers from the garden of her château at Bellevue. The château was built for Madame de Pompadour in 1750, when she had become more of a friend and confidante to the king and had become increasingly active as a patron of the arts. There Basseporte worked assiduously outdoors in the summer heat to capture the flowers at their prime. In an 1861 biography of the artist, Basseporte is said to have incurred debts from the artisans she enlisted to create the “bordures très-riches,” likely referring to the decorative red and gold borders of the drawings that were commissioned by Pompadour. In 1749 Madame de Pompadour advocated for a raise in Basseporte’s salary, and Louis XV obliged. That Pompadour commissioned the comparable set of drawings in the Bibliothèque nationale de France around 1750 raises the question of whether she is also the patron responsible for commissioning the Morgan’s series of botanical studies.

One noteworthy example demonstrating Basseporte’s mastery of watercolor is the Morgan’s Bizarre Carnations (Figure 1), which can be considered with a similar composition in the Paris album (Figure 2). The Morgan drawing depicts three efflorescent Bizzares, which are a strain of striped carnations popular in the eighteenth century, now lost to cultivation. These highly prized flowers could bloom much larger than today’s breed, as shown by the large central flower. A small red beetle takes up residence in the lower right of the frame, and the observant viewer will notice the barely discernible spider, whose ultra-thin, single strand bridges two of the flowers. The Bibliothèque nationale’s drawing similarly presents a well-articulated stem with its flowers in varying stages of development, from full to partial bloom, and in buds extending past the frame, threatening to blossom off the paper. The multiple angles and stages of the plant with its clearly defined individual parts demonstrate Basseporte’s ingenuity in delivering a scientifically accurate illustration while also producing a drawing that is exquisite to behold. Both drawings appear to have a higher degree of artistic intention than the clearly scientific function of many of the illustrations that appear in the loose vellums in the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris, which typically include only one specimen and emphasize the plant’s structure, often including cross-sections.

Although most botanical illustrations of the time feature a specimen against a blank ground, three of the Morgan drawings and one from the Paris album (Figure 3) are shaded with gray wash in the upper left quadrant (Figure 4) (1952.29:24; 1952.29:32; 1952.29:61). All four illustrations depict white flowers, which suggests that the shading was necessary to create contrast between the white flowers and white background. This unique characteristic further connects the two sets of drawings and supports a common date of creation and attribution to Basseporte.

Figure 5: Madeleine Françoise Basseporte and her circle (1701–1780), Elebore Christmas rose (Helleborus niger) , acc. no. 1952.29:23

Basseporte remained committed to her lifelong work as a botanical artist, and many of her drawings in the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle date from her seventy-ninth year. A simple explanation for the less precise drawings may be that Basseporte’s diminishing eyesight made drawing difficult. An alternative explanation could be that Basseporte’s students assisted with or created some of the drawings. Basseporte taught several important women of science, including anatomist Marie Marguerite Biheron (1719–1795) and possibly the botanical illustrators Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744–1818) and Marie-Thérèse Reboul (1738–1806), in addition to both daughters of Louis XV. An intriguing, unsigned note in the curatorial file mentions that Basseporte often instructed young women from a local Parisian orphanage in the art of botanical illustration and employed them as studio assistants. Nina Gelbart, a professor at Occidental College who specializes in Enlightenment women and has a chapter devoted to Basseporte in her publication Minerva’s French Sisters, confirmed that Basseporte enlisted orphaned women as assistants and left art supplies to these women in her will. It is possible that some of the Morgan works that appear to have a mixed level of skill may be the work of Basseporte and her students. For example the stem in Elebore Christmas rose (Figure 5) shows evidence of changes made to the composition, with visible erasure marks that may indicate a less-assured hand, perhaps that of a student, while the petals demonstrate a confidence of the brush, expertly rendered in watercolor fine enough to be by an experienced artist such as Basseporte.

Existing on the border between art and science, natural-history illustrations offered a point of entry for women into the world of art and royal patronage. It was often a network of women who supported one another as teachers, patrons, and collaborators. Unbeknownst to Jessie Morgan, an enthusiastic collector of botanical works and an avid watercolorist herself, this large cache of luminous vellums chronicles not just the Enlightenment obsession with documental natural-history specimens but also the opportunities the era provided for talented women seeking a career in the arts.

Mary Creed

Zukerman Departmental Assistant

Department of Drawings and Prints

The Morgan Library & Museum