When I joined the Morgan’s Department of Drawings and Prints as a graduate intern in 1993, one of my tasks was to aid Ruth Kraemer (1908–2005), the department’s indefatigable researcher who assisted curator Cara Dufour Denison with cataloging the French drawings. Ruth would give me her entries, first written longhand on legal paper and then typed on the department’s IBM Selectric and hand corrected, so I could enter them into the computer. I would print the results for Ruth to proof and then do a final round of corrections before presenting her with the completed entry. After I became the department’s curatorial assistant in 1998, I would find myself at my desk—often weary and late at night—typing up her texts, hoping to get them done before she came in the next morning and thus avoid a stern remonstration. Gradually, I became less intimidated by her as I learned that Ruth’s career was a model of perseverance and not privilege. Her story was entwined with the history of the Morgan and a direct result of its championing of women in the 1930s.

Fig. 1: Ruth Kraemer, ca. 1930

Ruth Schweisheimer was born in Munich in 1908 (her surname was later Americanized to Shearer). As a student, she had a tremendous facility for languages, which were the focus of her studies until she discovered art history. She quickly added Renaissance art to her course load alongside the philology of romance languages and archeology. A lasting image I have from listening to Ruth’s stories of her years as a graduate student is of her as a young woman pedaling her bicycle from church to church in Munich or Paris or Florence, with her camera in the basket, gathering research photos. In 1932, shortly before Hitler became German Chancellor, Ruth completed a dissertation devoted to the Bavarian rococo sculptor Johann Georg Dirr (1723–1779) at the University of Munich.

She took a job at the State Art Library but was soon dismissed as the Civil Service Restoration Act, passed in April 1933, prohibited Jews from being civil servants. She quickly pivoted, honing her photography skills and briefly opening her own photo studio. Further warning signs convinced her of the imminent need to leave Germany. Her father lost his job as a senior manager at Munich’s Metall-Atzwerk in 1935. While Ruth left Germany for the U.S. in September 1936, her family stayed behind. Tragically, her mother died in 1941, and her father, brother, and sister perished in 1942 in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Before fleeing Germany, Ruth had met a young law student named Helmut Kraemer (1914–1977). They would reconnect when he came to New York in 1937 and marry in 1939.

It was shortly after Ruth arrived that she came to the Morgan Library. Her friend Helen Franc, a graduate student at the Institute of Fine Arts studying Italian painting, was hired at the Morgan in September 1936 (Franck would resign in 1942 to work in the Office of War Information). The Morgan’s director, Belle da Costa Greene, hired Ruth soon thereafter to aid in the cataloging of German periodicals. When the project reached an end in 1939, Ruth put her skills at iconography to work at Princeton’s Index of Christian Art for two years.

Helmut passed his bar exams in 1940, and Ruth soon left her position to raise their two children. For Ruth, this was only a hiatus in her career as an art historian, though for other women at the time marriage effectively brought an end to their careers. In the 1930s and 40s, Greene had hired several women to assist with the cataloging of drawings and prints and to facilitate the Morgan’s study room, including Mary Anne Farley (in charge 1942–45), who resigned from tending to the collection shortly after her marriage to Captain Edward Tully.

In 1962, with her children grown, Ruth returned to the Morgan. She continued to research and publish the library’s collections until her retirement in 2002, at the age of 94. Her skills as a paleographer and iconographer served her well as she assisted curator Felice Stampfle with her catalog of the Netherlandish and Flemish drawings in the Morgan’s collection. In particular, Ruth tackled the complex subjects and Latin transcriptions found on 103 drawings by Otto van Veen, which appeared in Stampfle’s 1991 tome. This was typical of Ruth: intellectually curious and willing to address the thornier works or those deemed minor and of lesser priority, which she always treated fully, elucidating a narrative for even the slightest of sheets.

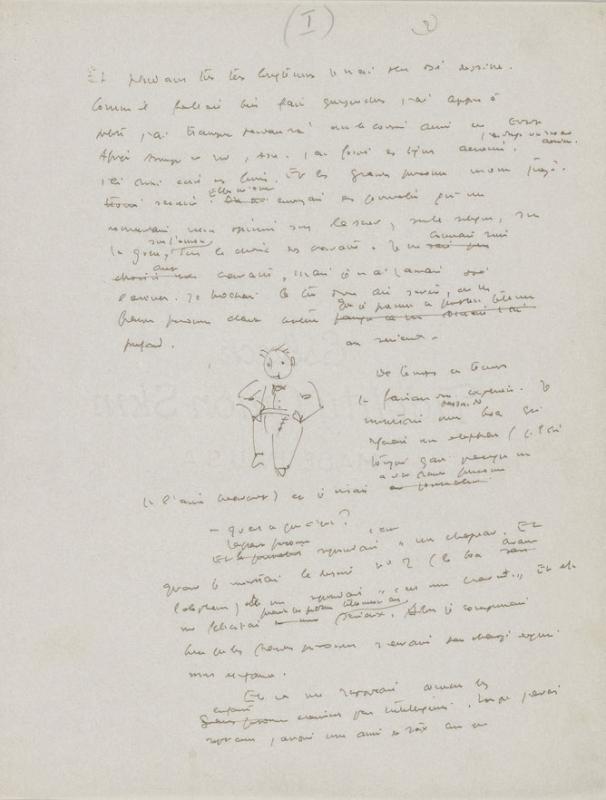

Ruth’s ability to dig deep into a subject and address large groups of drawings was nowhere more evident than in her work on the 1975 exhibition and catalog of the Morgan’s more than 250 drawings by Benjamin West and his son Raphael Lamar West. She also produced thorough and comprehensive articles on book illustrations by the eighteenth-century French draftsmen Hubert-Francois Gravelot and Charles-Nicolas Cochin. These articles were published in the pages of Master Drawings, a journal edited by Stampfle. Ruth often helped with translations and proofreading pages for the journal. Her keen eye for language and the written word also meant that she was the first person on staff to turn to with a challenging inscription. Ruth notably transcribed the hard-to-read handwritten manuscript of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince in the Morgan’s collection, in addition to deciphering, transcribing, and translating a vast number of letters and documents, including the sixteenth-century text found in the “Drake Manuscript” (Histoire naturelle des Indes, ca. 1586).

Rarely a week goes by when I don’t come into contact with Ruth’s work. Every time I grab a file on a French drawing, I come across Ruth’s notes, handwritten and typed, her call slips from the New York Public Library or the Frick Art Reference Library, her correspondence and requests for photographs, her perfectly produced and annotated photocopies. She reached out to scholars around the world to solicit opinions and exchange photographs in the years before the Internet became a principal source for images and before collections were digitized. Years from now, curators in the department may not know her handwriting or recognize who it was that undertook the fundamental research that paves the way for ongoing scholarship.

Among my fondest memories are the days that Ruth and I would go to lunch next door to the Morgan at the French-owned café Chez Laurence. We ordered the soup of the day, typically a savory green potage, and shared a sandwich. We almost always split a delicious almond paste and pear tart, her favorite, as we chatted over our coffee. She would graciously answer my questions about her past, but she also had questions for me.

Ruth eagerly embraced having the Internet at home and took great delight in communicating with her children and grandchildren via email. Ever ready to adapt and change and learn new things, Ruth was not in the slightest daunted by the increasing reliance on electronic communication.

The example of her rigorous work ethic is still with me, especially during this period of remote work as I strive to improve our online catalog records for French drawings. Her ability to embrace change, confront obstacles, and stay intellectually engaged—finding the challenge and reward in almost any assignment—is as much a part of her legacy as her carefully prepared notes and research in the files.

Jennifer Tonkovich

Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator

The Morgan Library & Museum