As if genius is not enough, a lyric poet has got to be in love. Pierre de Ronsard was still serving his literary apprenticeship in 1545 when he met Cassandre Salviati at a ball in the Château de Blois. Around fourteen-years-old at that time, she was the daughter of a Florentine banker who helped to finance the reign of Francis I. She married a local nobleman a year later, but that was not an obstacle to the conventions of courtly love. She was Ronsard’s muse, a source of inspiration like Beatrice was for Dante and Laura for Petrarch. He dedicated to her odes and sonnets now famous in French literature, most notably “Mignonne, allons voir si la rose.” That seize-the-day set piece compares favorably to equivalents in English such as Herrick’s “To the Virgins to Make Much of Time”” and Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress.” In a similar vein Ronsard urged Cassandre to admire the transient beauty of the rose and live for the moment―for her charms would not last for long.

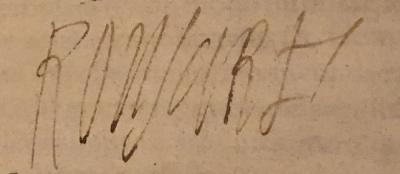

Ronsard’s signature in Lycophron, Alexandra (Basel, 1546). Gift of the trustees of the Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection, 1977.

One of his books now at the Morgan shows how he savored Cassandre’s name, melodious in its own right and full of meaning for a student of the Greek and Latin classics. After resisting the advances of Apollo, the mythological Cassandra was blessed and cursed with the gift of prophecy—blessed because she could see into the future but cursed because no one would believe her when she foretold the fall of Troy. The doomed Trojans thought that she was raving mad. She was the subject of the dramatic monologue Alexandra by the Hellenistic poet Lycophron, a work so obscure that the title-pages of early editions confess that it is barely comprehensible.

The Morgan has a copy with Ronsard’s signature on the title page along with a commendatory inscription by his Greek instructor, Jean Dorat. The master wrote a gracious compliment to his star pupil comparing him to the Greek poet Terpander. One or the other jotted marginal comments about difficult passages. Opinions are divided about the annotations, and at least four scholars have proposed different attributions. It would be good to know who should get the credit for a Greek distich making poetry akin to madness: “if Cassandra were alive today she would not have spoken any differently in her delirium than Lycophron when he is being lucid here.”

Ronsard was studying Lycophron in the late 1540s, just when he was starting out on his literary career. Later he would look back at his learning period and express his gratitude to his teacher. Like Lycophron, he too would mystify his readers.

Le jour que ie fu né, Apollon, qui preside

Aux Muses, me seruit en ce Monde de guide,

M’anima d’vn esprit subtil & vigoureux,

Et me fit de science & d’honneur amoureux.

En lieu des grands tresors & des richesses vaines,

Qui aueuglent les yeux des personnes humaines,

Me donna pour partage vne fureur d’esprit,

Et l’art de bien coucher ma verue par escrit.

Je n’auois pas quinze ans que les monts & les bois

Et les eaux me plaisoient plus que la Cour des Rois.

Ainsi disoit la Nymphe, & de là ie vins estre

Disciple de Daurat, qui long temps fut mon maistre,

M’apprit le Poësie, & me monstra comment

On doit feindre & cacher les fables proprement,

Et à bien déguiser la verité des choses

D’vn fabuleux manteau dont elles sont encloses.

When I was born I took Apollo’s way

To guide me through this world and thrive today.

The Muses’ lord inspired in me a love

Of noble knowledge proudly set above

The futile lust for treasure piled on high

And riches vain that blind the human eye.

Instead he gave a gallant legacy:

The skill to flex my strength in poetry.

By age fifteen, the mountains, woods and springs

Meant more to me than paying court to kings.

Thus prompted by a nymph from there I went

To be a student of Dorat. Intent

On his lessons firmly I applied

Myself to verse for years and learned to hide

My wit in fables, an adroit disguise,

A cloak in which a key to wisdom lies.

Ronsard was not shy about his genius or his muse. He commissioned a portrait of Cassandre, age twenty, which faces a portrait of him, age twenty-seven, in his early publications. Inside the border of his portrait is a Greek motto declaring that “I went mad as soon as I saw her.” Her motto plays on themes in Horace and Ovid but can be taken at face value to mean a mutually devouring passion. The soulmates gaze in each other’s eyes across the two-page opening, all the more reason to pose them in profile like the ancient cameos highly prized during the Renaissance.

Ronsard wears the laurel crown as if he had been acclaimed Poet Laureate in the tradition of his classical forebears or his role model Petrarch, who won that honor in 1341. His rivals accused him of arrogance—this is a case in point—but he did gain special status and royal favor. If not Poet Laureate, he could at least be Prince of Poets, a title coined by his friends in the 1550s.

Mosaic binding on the Ronsard volume. Purchased on the T. Kimball Brooker Sixteenth-Century Fund and as the gift of T. Kimball Brooker, 2021.

The Morgan recently acquired a volume containing three of his early publications: Le Bocage (Paris, 1554), Les Quatre premiers livres des odes (Paris, 1555), and Le Cinqieme des odes (Paris, 1553). They are in a splendid binding (more about that in a moment). All three were issued by the same publisher, Catherine L’Héritier, the widow of Maurice de La Porte; all three contain the portrait of the author; and they have other traits in common revealing how he published his work and managed his reputation. The Bocage contains a royal privilege giving him exclusive rights to his writings present and future, a document printed here for the first time. It is remarkable in that it confers these prerogatives on the author rather than a member of the book trade. Ordinarily Catherine L’Héritier would have been named in the privilege, but she had to pay the poet for the manuscripts of the Bocage and the Quatre premiers livres des odes and could issue those works only for the term of six years. This privilege reverses the relationship between author and publisher for the express purpose of encouraging arts and letters in the kingdom and creating a model of French language, “hitherto lacking in refinement.” In a legal sense, it makes literature part of the Renaissance cultural agenda, an instrument for the greater glory of king and country. Ronsard used this opportunity to issue his works in a uniform format, which is evident in these three publications. So, both in style and substance, the author was taking control of his work.

He published a collected edition in 1560, but even before then, he was inviting his readers to assemble his work on their own. These 1550s editions can be found in similar composite volumes at the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the University of Virginia. But the Morgan volume is distinguished by its noble provenance and its ambitious binding. A contemporary connoisseur of Ronsard’s poetry recognized the importance of this book and had it bound in dark brown morocco decorated in the mosaic style with a vine-leaf motif and a strapwork frame in different colored leathers. Its flat spine displays a vine-leaf pattern similar to other reliures à grands décors. It is one of the earliest known examples of French poetry in a luxury armorial binding executed at the time of publication. Previously, collectors adopted this style to consecrate classical texts and vernacular imprints of antiquarian interest. It was exhibited in a 1985 Ronsard exhibition where it exemplified new developments in French Renaissance culture—the emergence of ambitious libraries, formerly the exclusive province of royalty and the high nobility, as a kind of conspicuous consumption.

The self-assertive owner of this volume was Pierre de Brisay de Denonville (1523–1582). He signed his name on the title page and had it tooled in gilt on the front cover, which also displays his arms. A family archive survives with vivid details about his career in the church and court. Nephew of a cardinal, he was the abbot of a wealthy Benedictine monastery, which provided the means to maintain and fortify a château and other secular holdings. Eventually he left the church and converted to Protestantism but continued to draw a salary from the monastery he abandoned. He obtained sureties from the king to protect his property, got married, and started a family. His son Jacques de Brisay de Denonville inherited his estate over the objections of an uncle who expected to be next in the line of succession. The uncle tried and failed to delegitimize the children of the apostate monk. A staunch Protestant, Jacques de Brisay led a cavalry detachment to defend his Dutch coreligionists but died at the siege of Breda in 1625. He was succeeded by another Pierre de Brisay, who did his part to perpetuate the family by having fourteen children. The family stayed in favor with the crown after he converted back to Catholicism. Some of his descendants took holy orders, some fought in the wars of Louis XIV, and one became Governor General of Canada.

We are still looking for information about the family library. The bibliophile Pierre de Brisay commissioned other luxury bindings on books printed in the 1550s. Jacques de Brisay was sufficiently interested in the library to sign his name in the Ronsard volume. Later generations built a new château, but by 1910 it was in ruins. The books could have been dispersed long before then for any number of reasons: financial problems, the Revolution, or the changing priorities of the family, which owned other properties including the Guermantes estate made famous by Proust’s The Guermantes Way. The earliest auction record we can find for the Ronsard volume is the Paul Portalier sale in 1929, when it fetched 50,000 francs, a handsome sum recognizing the importance of the binding.

We are very grateful for the expert advice of Roland Folter, who has a catalogue of that sale annotated by the eminent bookseller Arthur Rau (1898–1972). Born in London, educated at Oxford, Rau managed the Paris branch of the venerable Maggs Bros. establishment and then founded his own firm at the high end of the antiquarian book trade. His connoisseurship, phenomenal memory, and eclectic tastes were legendary. He marked up the catalogue description of the Ronsard volume as if he had purchased it, whether for himself or a client is not clear. The 50,000 francs he noted in the margin corrects the printed price list, which inadvertently dropped a zero. It is said that he did not hold on to his books for very long. If he sold this one quickly, he could have turned a profit, for the French economy was still going strong at that time. Then we lose sight of it until it reemerged in the library of the Swiss collector Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller, perhaps best known for his contributions to the Barbier-Mueller Museum of ethnographic art in Geneva. He donated seven hundred volumes of Italian Renaissance poetry to the University of Geneva. His first love, however, was the work of Ronsard and his circle, which he collected in depth, even selling off other holdings to concentrate on what he called Ma bibliothèque poétique. He owned at least one other Ronsard item that had been in the Portalier sale. The Pierre de Brisay binding was the cover image of a 2007 exhibition catalogue of his collection, aptly titled Mignonne, allons voir. We are very grateful to Morgan trustee T. Kimball Brooker, who spotted it in the catalogue of the Barbier-Mueller sale, 23 March 2021, and gave us the means to bid on it.

That lot was hotly contested, but we prevailed. T. Kimball Brooker urged us to pursue it because he perceived intriguing connections with two Morgan collections. It complements our holdings of French Renaissance bindings, some decorated in similar styles and marked with the ownership insignia of equally interesting contemporary collectors. And it joins other Ronsard volumes no less important for the study of the Prince of Poets. The Morgan has nearly ninety items by and about him including his first appearance in print and his last verse published just after he died in 1585. To remember him in his prime, the compilers of the posthumous edition printed the portrait once again above an epitaph composed for the occasion:

Tel fut Ronsard autheur de cet ouurage,

Tel fut son oeil sa bouche & son visage,

Portrait au vif de deux crayons diuers,

Icy le corps, & l’esprit en ses vers.

Suchlike was once Ronsard—his eyes, his face,

His mouth—the author’s traits of which to trace

A portrait true one lets it twice appear:

The soul in verse bound with the body here.