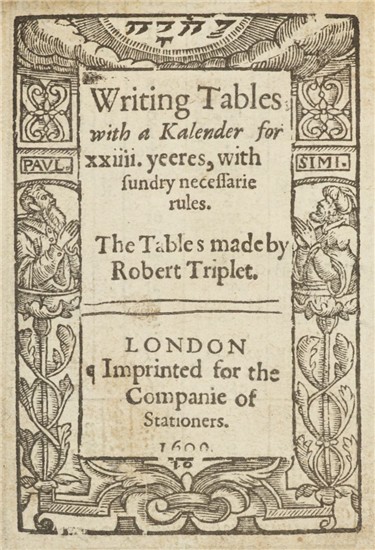

Writing Tables with a Kalendar for xxiii Yeeres, by Robert Triplet. London: Companie of Stationers, 1609. The Morgan Library & Museum; purchased by Pierpont Morgan before 1913.

Before the electronic mobile device, before the blank book, after the wax tablet, how did people take notes? A look at a rare example of a Renaissance erasable pad and its contemporary counterparts.

Many of us keep diaries in an attempt to capture time—to leave a physical trace of our being even after we’re gone. But some personal writings are ephemeral, disappearing from view almost as soon as we’ve committed our thoughts to paper or screen. When we send our Facebook posts or Tweets out into the world, we create a kind of moment-by-moment diary, letting friends know what’s on our minds. But the focus is much less on the preservation of memory than on the instant communication of impressions. And while technology does offer powerful tools to capture and store such digital diaries for the future, chances are most of us are not requesting a yearly spreadsheet of our Tweets for our personal archive. We Tweet in the moment, and then the moment is gone, and it’s on to the next.

Writing Tables with a Kalendar for xxiii Yeeres, by Robert Triplet. London: Companie of Stationers, 1609. The Morgan Library & Museum; purchased by Pierpont Morgan before 1913.

As I thought about such disappearing diaries, I looked at a worn but extraordinary object in the Morgan’s collection that might be considered a precursor to both the pocket diary and the handheld electronic device. Robert Triplet’s Writing Tables with a Kalendar for xxiii Yeeres, published in London in 1609, is about the same size as an iPhone. It includes a printed calendar that covers several years. But most intriguingly, it also includes a few strange, stiff blank sheets toward the middle. These are erasable pages, once specially treated with a coating of gesso and glue. Much like a smartphone owner, the user of this little book could tuck it into a pocket for easy reference, and even make notes on the go with a simple stylus (no clunky pen and ink required!). Later, when the notes were no longer needed, they could be wiped away. The book even includes instructions for erasing and rewriting: “Take a litle peece of Spunge, or a Linnencloath, being cleane without any soyle: wet it in water” and “wipe that you have written very lightly, and it will out, and within one quarter of a hower you may write in the same place againe.”

What a fascinating little object! Such calendars with erasable pages were common during the Renaissance, but very few survive because they were worn to bits and discarded when no longer useful. Even (the fictional) Hamlet used one: after seeing the ghost of his father, he declares, “Yea, from the Table of my Memory, / I’ll wipe away all triuiall fond Records. . . .” (If you want to know more about writing tables and erasable paper, look for the excellent scholarly work of Peter Stallybrass, Roger Chartier, J. Franklin Mowery, and Heather Wolfe.)

Song Dong’s water diary.

If Hamlet was able to wipe away memory by cleaning off his erasable sheets of paper, an even more dramatic example of the fleeting diary is that of the Chinese conceptual artist Song Dong. In the 1990s, Song Dong began to make daily diary entries, painting them with water on stone. Each calligraphic entry quickly evaporates, leaving no trace. Rather than creating an indelible record, Song Dong leaves nothing behind. This process frees him from considering who might read his words one day, because the answer is clear: no one. Thus he’s spared the dilemma that John Steinbeck articulated so well: “I have tried to keep diaries before but they didn’t work out because of the necessity to be honest.” Song Dong dramatizes what is true for many diarists—that it is the release of thought and emotion—the veryact of putting pen (or brush) to paper (or stone) that matters.

Christine Nelson is the Morgan’s Drue Heinz Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts. The Renaissance erasable tablet she describes in this post is on view until May 22 in the exhibition The Diary: Three Centuries of Private Lives.