“...we are each other’s

harvest:

we are each other’s

business:

we are each other’s magnitude and bond.”

Gwendolyn Brooks, “Paul Robeson” from Blacks (1983).

Last year, the Morgan acquired more than seventy books and some manuscript material related to the American poet Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000), including a portion of her personal library, adding to our holdings of Brooks manuscripts. Brooks is probably most well known for being the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize in any category when she won the Prize for Poetry in 1950 for her book Annie Allen. However, Brooks’s creative career spans far before and long after that momentous event. As a Belle da Costa Greene Curatorial Fellow at the Morgan, I have been researching, reading, and learning more about Brooks in preparation for an upcoming exhibition on her life and work. What has struck me most in engaging with Brooks’s life and work are the relationships she cultivated and how these relationships were reflected in her work and the work of others. Brooks took up not only the role of poet but also that of mentor, teacher, friend, community leader, and publisher. All of these roles have had an impact on her literary legacy.

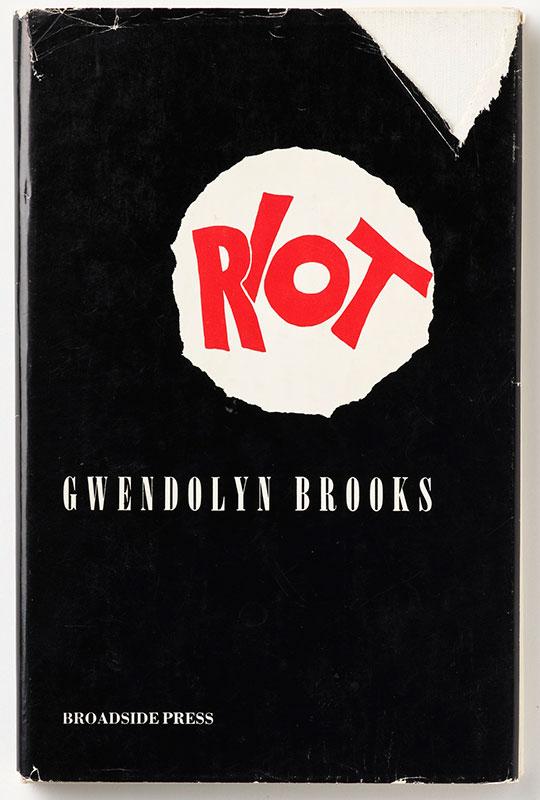

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000). Maud Martha: A Novel. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1953. The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; PML 184292.

Brooks started exploring creative writing at a young age, keeping a writing journal from the age of eleven and publishing her first poem at the age of thirteen. She began her career writing about what she saw, heard, and felt in the predominantly African American Chicago neighborhood of Bronzeville. Reflecting on her youth, Brooks once said, ”. . . it did not occur to me, even once, that the black in which I was encased (I called it brown in those days) would be considered, one day, beautiful.” Brooks made it her job as a poet to speak to the beauty of her community.

Her works, such as A Street in Bronzeville (1945) and Maud Martha (1953), were influenced by the people in Gwendolyn’s daily life—the people she connected with and observed on the streets of her neighborhood. Specifically, she portrayed scenes of urban African American daily life, a subject that was otherwise generally ignored in popular writing at the time. Her subjects were the preacher, the everyday woman, the young dark-skinned girl. Her empathetic treatment of day-to-day struggles of African American people, from dealing with systemic racism and poverty to moments of joy and love, painted intimate and relatable portraits of her community.

Though her earlier work was in a way revolutionary for its depiction of Black inner life, the publication of her work was within a predominantly white context and for a predominantly white audience. However, something changed in 1967: a new political consciousness was forming, along with a new community of artists. Brooks became a teacher and mentor to younger African American poets in Chicago. These young artists brought with them new perspectives on the issues of racial inequity and global anti-blackness. These interactions introduced Brooks to the growing movement for Black Power. In community with members of the Black Arts Movement in the 1960s, Brooks’s work shifted from introspective to more transformative and revolutionary.

Part of Brooks’s commitment to this community included publishing under Black-owned publishers and printers, such as Broadside Press, one of the first Black-owned presses in the United States, founded in Detroit by the poet Dudley Randall, and Third World Press, a Black-owned press started by Haki R. Madhubuti, a young mentee of Brooks. These presses provided Brooks and other African American writers a platform and freedom to speak specifically to Black audiences. Several of the Morgan’s recently-acquired works are inscribed copies of books produced by these presses, which can often be identified by their bold and colorful covers and pro-Black imagery.

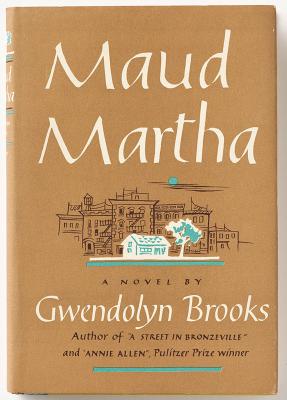

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000). Riot. Detroit: Broadside Press, 1969. Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe, Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198519.

Brooks’s 1969 book of poetry, Riot, exemplifies the influence of these political and personal relationships on her work. A documentation of the reaction to disturbances in Chicago after the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968, Riot is an attention-grabbing book of poetry with a black front cover, the title lettered in red inside a white circle, roughly-edged, as if it has been shot through or torn. Not only do the poems in this volume speak more directly to themes of Black Power and liberation, but Brooks also donated the royalties from Riot back to Broadside Press, showing her commitment to the work being done by the press.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000). Very Young Poets. Chicago, Illinois: Brooks Press, 1983. Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe, Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198653.

Influenced by her work with Broadside and Third World Press, Brooks even started two small presses of her own: Brooks Press and, later, the David Company. Through these presses, Brooks published her own poetry and other works, including guides for young poets. These guides, Young Poet's Primer (1980) and Very Young Poets (1983), were inspired by Brooks’s experiences teaching at schools and colleges throughout her career. The covers of these books, like the writing exercises in them, are simple and inviting to introduce a new generation of young people to the joy of writing poetry.

These periods of Brooks's work and these generative relationships are tied together by her powerful use of language, her deep empathy, and her incredible imagination. I am grateful to Brooks’s work for how it helps us to explore our own relationships and how these relationships change us and the world around us.

Nicholas Caldwell

Belle Da Costa Greene Curatorial Fellow

The Morgan Library & Museum