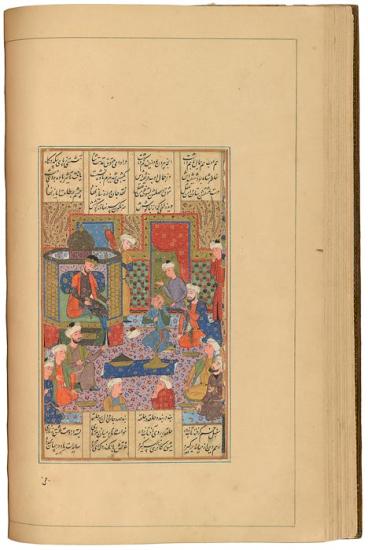

Maḥmūd of Ghanzi Orders His Favorite Page, Ayāz, to Cut off Half of His Beautiful Curly Locks

Haft aurang (Seven Thrones), in Persian, written by Ḥasan al-Ḥusainī

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

Maḥmūd of Ghazni (r. 997–1030) was the greatest ruler of the Ghaznavid dynasty, controlling Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwest India. He was the first to bear the title Sultan (authority), was a patron of the arts and of poetry, and commissioned Firdausī to write his famous Shāhnāma, the Persian national epic. But he became even more celebrated, by such poets as Jāmī and Sa˓dī, because of his love for Malik Ayāz, his young male slave. When the king asked him if he knew of a greater and more powerful king, he said yes, explaining that even though Maḥmūd was king, he was ruled by his heart, and that Ayāz was the king of his heart. Thus, the power of Maḥmūd's love made him a slave to his slave.

Jāmī's Haft aurang (Seven Thrones or Constellations of the Great Bear), was written from 1468 to 1485, and consists of seven poems in masnavī form (rhyming couplets); some are allegorical, others are didactic. In his discourse on beauty he tells the story of Maḥmūd and his love for Ayāz, who had many good points, but was not remarkably handsome. One night, under the influence of wine and Ayāz's beautiful curls, love and desire began to stir in him, and he feared that he might verge from the Path of Law and the Way of Chivalry. He then gave Ayāz his knife, ordering him to cut off half the length of his curls, which he did. His ready obedience provided a new rush of love, causing him to bestow upon Ayāz even more gold and jewels, after which Maḥmūd fell into a drunken sleep. In the morning, realizing what he had done, called for Ayāz and saw the clipped tresses. He was somewhat cheered by the poet Unsuri's quatrain.

Though shame it be a fair one's curls to shear,

Why rise in wrath or sit in sorrow here?

Rather rejoice, make merry, call for wine:

When clipped the cypress doth most trim appear.

In 1021 Maḥmūd gave Ayāz the throne of Lahore. Maḥmūd himself died at fifty-nine, had nine wives, and nearly fifty-six children with almost three dozen women.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.