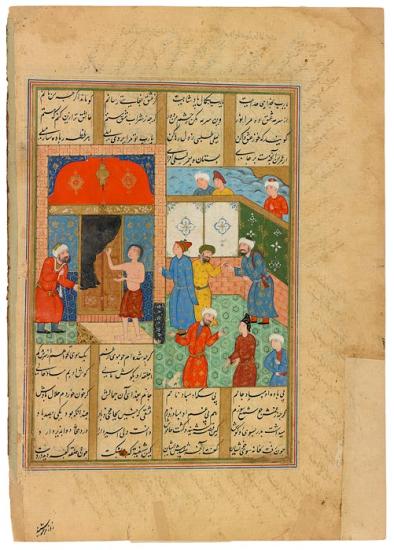

Majnūn Grasps the Door Knocker of the Kaaba

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, illustrated ca. 1579 by Siyāvush the Georgian and his workshop for ˓Alī Khān (Beg Turkman).

Bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

In order to cure Majnūn, his father takes him on a pilgrimage to Mecca, where he hopes that his son will ask to be saved from his passion. Instead, Majnūn grasps the door knocker of the Kaaba and cries, "I pray to You, let me not be cured of love, but let my passion grow! Make my love a hundred times as great as it is this very day!" Nothing further can be done, for Majnūn can never be cured, having blessed Lailā and cursed himself before the Holy Shrine. His father, full of grief, returns home, and Majnūn, whose life is threatened by Lailā's father, again retreats into the desert.

Lailā va Majnūn (1188), a Persian Romeo and Juliet, is the third poem of the Khamsa (Quintet), a multi-part work by the poet Niẓāmī. The story is based on two real-life seventh-century lovers.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.