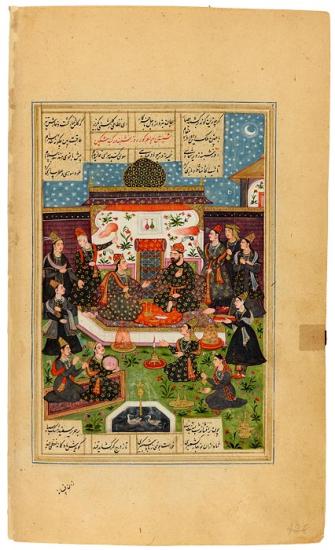

Bahrām Gūr and the Indian Princess Fūrak in the Black Pavilion

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

On Saturday, the day of Saturn, dressed in black, Bahrām Gūr visits the Black Pavilion. During the day, in the darkness of the Black Pavilion, he enjoys the charms of Fūrak. When night falls—note the moon and stars—Fūrak tells the following story.

A king visited the City of the Stupefied, where all wore black, but nobody would tell him why. A bird transported him from the top of a tower to a garden. When night fell lovely maidens entered the garden, followed by the queen of the magical creatures, whom he tried to seduce. After thirty attempts he resorted to force, and found himself returned to the bottom of the tower. He then understood why all wore black and henceforth did as well.

The Seven Princesses

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

One day, in his castle in Khavarnak, Bahrām Gūr comes across a secret room that had been overlooked by his keeper. After entering the room he sees portraits of seven princesses with whom he instantly falls in love. Among the portraits was one of a young man inscribed with his name, an omen of things to come. After receiving permission from their fathers, he marries them all, building for each a domed pavilion with a color scheme symbolizing the country from which each came. The colors also symbolize the days of the week and the planets for which they were named. Each princess is asked to tell a sensuous story matching the mood of the color. "Even as the planets move, so then shall I," says Bahrām, and "I will visit one pavilion a day from the first of the week to the last." He apparently followed the cycle for at least seven years.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.