This is a guest post by Paris Shih, a Taiwanese writer, cultural critic, and Ph.D. candidate in English at the CUNY Graduate Center.

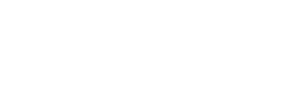

In “The Birthday of Madame Cigale,” Aubrey Beardsley’s famous Japonaiserie drawing for The Studio, the ceremonial scene is rendered through the style of the Kanō school as well as the genre of ukiyo-e. Popular during the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, ukiyo-e, literally meaning “the picture of the floating world,” captures a wide range of characters, from the royal to the common, the fantastical to the ordinary. Beardsley’s employment of these aesthetic modes for the ceremonial scene is fitting. What is strange about the drawing is its racial figuration. With high noses and elf ears, these figures do not look particularly Japanese. Such a representation is a curious one, given the entire oeuvre of Beardsley. In his illustrations for The Yellow Book and The Savoy, for example, many of the European characters resemble western conceptions of East Asians, with flat noses and slanted eyes. These drawings function almost as inverted versions of each other, foregrounding the relational structure of race-making in nineteenth-century England. The decadent aesthetic that made Beardsley at once famous and infamous should therefore be seen as a racialized construct, one that potentially threatened the Victorian ideal of racial purity. What further upset Victorians at the fin de siècle, however, was not simply the spectacle of racial alterity but the emergence of another empire. Rising in the mid-nineteenth century, the Empire of Japan stood for a competing imperial force on the other side of the globe. Importantly, Beardsley’s illustrations were produced at the pivotal moment when the Japanese Empire captured the English imagination. To understand the racial logic of decadent arts, we must go beyond the Saidian definition of orientalism—East Asia, after all, was never Edward Said’s primary focus—and situate Japan in the context of global imperialisms.

The rise of Japan marked a turning point in the history of western orientalism. While interests in oriental arts could be traced to earlier periods, it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that conflicting ideas of Japan started to be crystallized into collectible items in the English household. The Kanagawa Treaty in 1854 and the Ansei Treaties in 1858 officially opened the gate of Japan to international markets, ending the isolationist policy known as sakoku. The 1862 International Exhibition, where Japanese arts and artifacts were displayed, further materialized the once-mythologized culture, turning domestic fantasies into global spectacles. These events led to what Samuel Yamashita calls the “Japanese turn” in European societies, shifting western imaginations of the Orient from the Middle East to the Far East.1 The “Japanese turn” revealed not only the uneven developments of orientalism but also the unstable structure of English imperialism. The previous wave of orientalism, where Victorians variously represented the Indian and Muslim world, was established upon hierarchical relations between England and its colonies. As Said points out, such orientalism “is based on the Orient’s special place in European Western experience. The Orient is not only adjacent to Europe; it is also the place of Europe’s greatest and richest and oldest colonies.”2 This definition, however, could not account for Victorian England’s complicated relationship with Japan. Japan, after all, was never colonized by England; it was, in fact, a colonizer itself. When Victorians encountered Japanese arts, they were thus confronting material representations of an imperial force. Simultaneously fascinated with and threatened by the emergence of another empire, they developed an ambivalent attitude toward Japan. As Grace Lavery argues in her important book, Quaint, Exquisite, “the construction of Japan as an aestheticized exception to various taxonomies of race, gender, nation, ethnicity, modernity, and culture was possible because Japan confronted the West as an Other Empire.”3 This was why, as she observes, the concept of Japan was marked by a set of paradoxes: “Japan was perceived as beautiful but dangerous; as ultramodern or postcapitalist, but nonetheless stilly immersed within the cocoon of tradition; as Westernized, but still as the most un-Western place conceivable.”4 Victorian Japan, then, became a site of ideological contradictions, at once embodying cultural desire and social anxiety in nineteenth-century England.

The “Japanese turn” also contributed to a renewed conception of what I call “oriental queerness,” meaning the peculiar nature and transgressive potential of oriental subjectivity in western imaginations. In the mid-nineteenth century, representations of the Orient were mostly built upon colonial relations, where writers employed metaphors of oriental femininity to suggest forms of moral corruption and subordinate positionality. Jane Eyre, in particular, is notable for its “metaphorical use” of “dark races,” including Indians, Persians, and Turks.5 With the rise of Japan, however, the Orient was reconceptualized as a site of cultural sophistication, artistic achievement, and, most importantly, imperial power. While Japan was feminized by Victorians, it also stood for a feminizing force, able to overtake the British Empire on the global stage. Facing the “Japanese turn” at the end of the century, writers and artists developed different strategies to represent the strange—and indeed, queer—presence of another empire. These strategies could be understood through two representational modes—the “satiric” and the “decadent.” In the first mode, the queerness of the empire was mediated through satiric representations, commonly found in trade cards, caricatures, and even operas. In the second mode, Japanese queerness was not only incorporated but also exaggerated, through which artists imagined transgressive forms of subjectivity along with the French decadent tradition.

“Queer and Quaint”: Operas, Trade Cards, and the Satiric Logic of Oriental Queerness

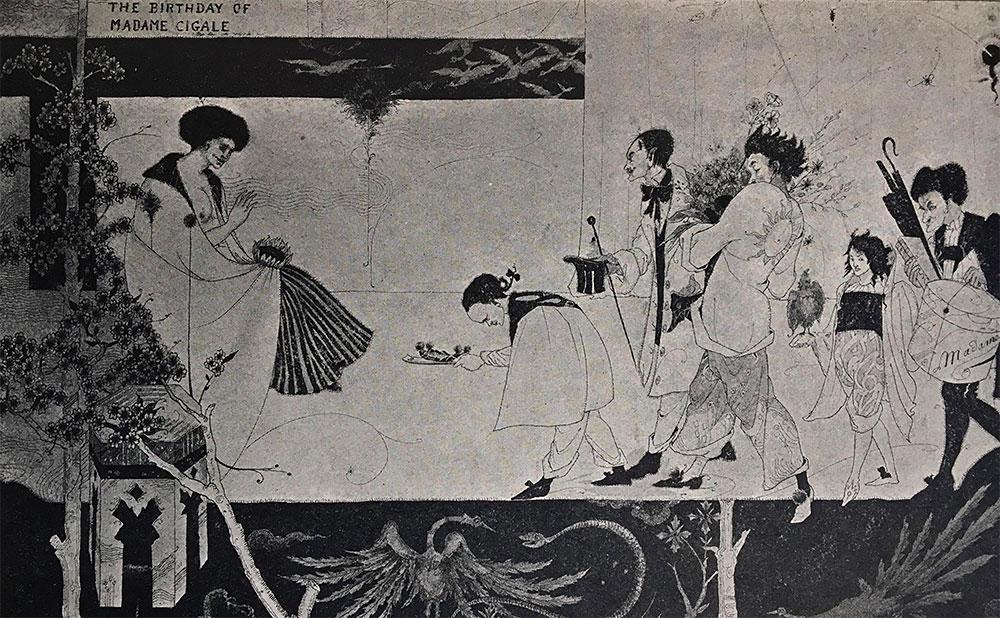

In a trade card circulated around the 1880s, a young lady in a yellow aesthetic dress is sitting in a garden of sunflowers and lilies, with her right hand holding a Japanese fan and her left hand an issue of Punch magazine. At that time, Punch was known for its caricatures of the aesthetic movement, with the female aesthete as one of its central targets. The humor of the trade card, thus, lay in its metafictional structure, and the fact that the caricatured figure is holding the source of the caricature herself. The British periodical forms a counterpoint to the Japanese fan. On the one hand, the picture highlights the fan through its blue and white color against the aesthetic yellow. On the other hand, it renders the oriental motif through a satiric mode, ridiculing the unnaturalness of the woman’s fascination with foreign objects. While aiming at alterizing cultural others, the process of satirization simultaneously denaturalizes the concept of “Englishness,” revealing the performative structure of English femininity through the alterity of Japanese presence. If the female aesthete’s obsession with Japanese artifacts was unnatural, then “English” subjectivity itself was no more “authentic.”

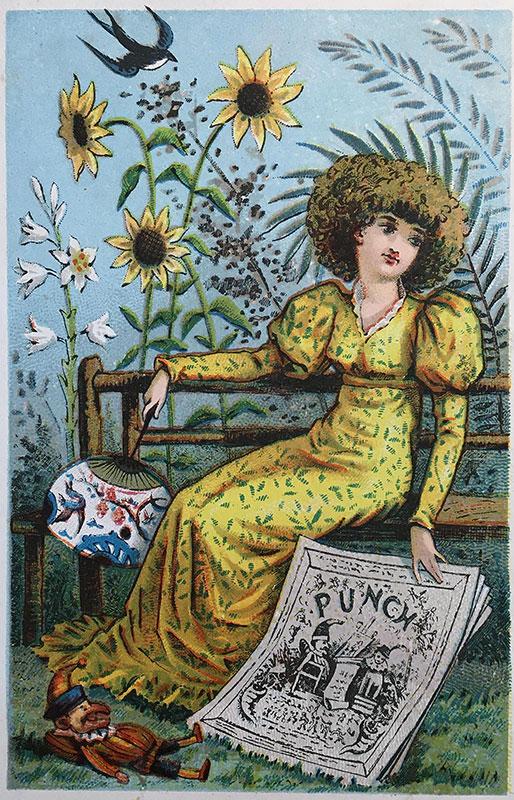

Such a dialectic between satire and orientalism could also be found in The Mikado, W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan’s comic opera about a fictional Japanese town. The opera famously opens with “Japanese nobles discovered standing and sitting in attitudes suggested by native drawing,” introducing themselves as figures “on many a vase and jar” and “many a screen and fan,” in manners “queer and quaint” (I. 1-2, 5-8).6 With such an opening, Gilbert and Sullivan present a meta-theatricalized Japan, emphasizing that their conception of the nation and its culture was largely based on paintings and art objects. As Carolyn Williams argues in her classic study on the Savoy Operas, “the characters acknowledge that they have sprung to life from collected artifacts and that the Japanese setting of the opera is literally a façade, a ‘screen’ in several senses of the term.”7 What was “queer” about Japan, then, was its artificiality, fictionality, and defamiliarizing effect. But the “queerness” of Japanese subjectivity still needed to be embodied by English actors. Comically rendered and campily exaggerated, the English embodiment of Japanese queerness foregrounded the theatricality of English subjectivity itself. Notably, these “Japanese” characters were portrayed differently in the original 1885 production. Some actors adopted what could be understood as “yellowface,” with Japanese make-up and slanted eyes, such as George Grossmith’s portrayal of Ko-Ko. Others, however, maintained their “English” looks. In a photograph captioned “Three Little Maids from School Are We,” the actors Sibyl Grey, Leonora Braham, and Jessie Bond were seen in kimono without “yellowface,” even as they performed “Japanese” poses. In many ways, the kimono accentuated rather than obscured their “Englishness,” as the incongruity between the fashion style and the performing body highlighted the actor’s racial characteristics. By embodying Japanese queerness, the actors exposed the strangeness of English femininity, denaturalizing a racialized ideal that eagerly pursued the state of naturalness.

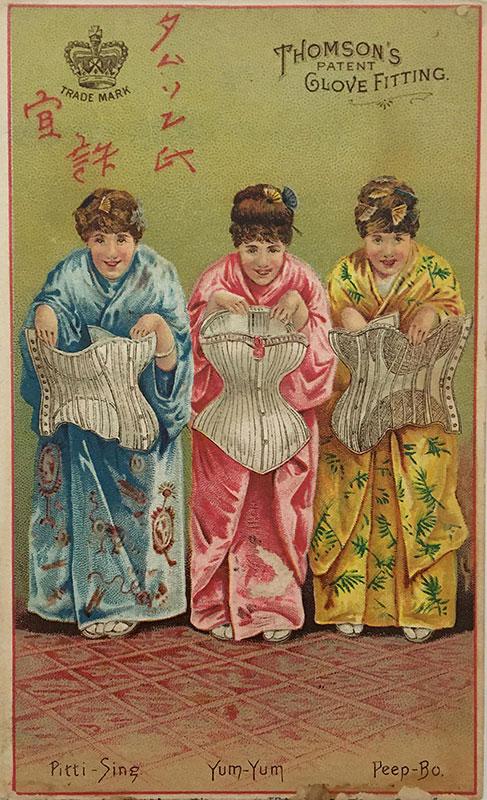

The defamiliarizing effect of such an embodiment was furthered by the commercial appropriation of the opera in nineteenth-century trade cards. Following the success of the opera, American businesses started to produce variations of trade cards based on its characters. The three little maids, in particular, were among the most reproduced figures in this wave of cultural imagination. In the card for Thomson’s Glove-Fitting Corsets, for instance, the three little maids are seen holding corsets of various styles that the company proudly carried. Marketed as “the most popular Corset throughout the United States,” the Thomson brand promised to comfortably reshape the wearer’s body and “produce a perfect figure.” Interestingly, the corsets are displayed by English ladies dressed in kimono, with comic gestures and funny faces. This commercial image not only creates another layer of satire on top of the satiric opera but also constitutes an inversion of the racial representation in the aforementioned trade card. While the previous card features an English lady in an aesthetic dress, here, the corset—an emblem of English femininity—is detached from the English female body, now adorned in oriental garments. With the “Englishness” of the actors remaining visible, the Japanese dress serves to distance the English style from the English body, foregrounding the material and performative structure of its femininity. What appears even stranger than the kimono turns out to be the corset. The “perfect figure” that the advertisement promised could therefore be seen as a racialized construct. Such a process of racialization relied not on the orientalization of the English body but on the estrangement of Englishness from that very body, rendering Englishness even queerer and quainter than the idea of Japan itself.

“Daughter of Sodom”: Wilde, Beardsley, and the Decadent Logic of Oriental Queerness

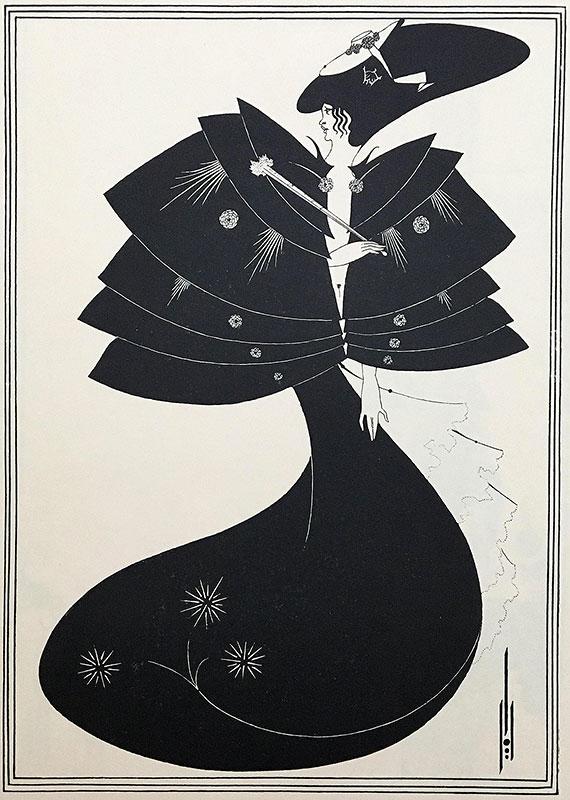

In “The Black Cape,” Aubrey Beardsley’s famous illustration for Oscar Wilde’s Salomé, the titular character is seen in a black gown inspired by the kimono and samurai styles. Different from the women in satiric representations, Salomé does not seem “English” or “European.” While the Biblical figure is supposed to be Jewish and was conceived through the persona of the French-Jewish superstar, Sarah Bernhardt, Beardsley’s Salomé looks neither Jewish nor French. Instead, she looks oriental. This illustration, along with Beardsley’s orientalized characters in The Yellow Book and The Savoy, point to another representational logic of oriental queerness. Rather than divorcing Englishness from the English body through Japanese fashion, Beardsley blurs the boundary between English and Japanese subjectivities, rendering his European figures always already orientalized. What unsettled Victorian society was not only the sodomitic potential of the Wilde text but also the specter of racial impurity. This strategy of representation, which aims at maximizing instead of toning down the threat of the Orient, exemplified what I call the “decadent logic” of oriental queerness, and it is through this logic that Beardsley conjured up another Japan in the Victorian mind.

Beardsley’s interpretation of Salomé marked his own “Japanese turn.” According to the Victorian art critic H. C. Marillier, Beardsley followed European art traditions in his early works and was indebted to the Pre-Raphaelite painter, Edward Burne-Jones. “Then the Japanese caught his wayward fancy,” Marillier remarks, “and gave us the ‘Femme Incomprise,’ ‘Madame Cigale,’ and indirectly much of The Yellow Book work.”8 However, Beardsley’s fascination with Japanese arts could be traced to earlier years. As Linda Gertner Zatlin notices, during his Brighton days, the young Beardsley was attracted to A. B. Mitford’s Tales of Old Japan, which features illustrations by a Japanese artist depicting grotesque bodies and monstrous figures. These images shaped Beardsley’s vision of “the Japanese grotesque,” a genre that he adopted and adapted for his future works.9 Notably, Beardsley’s futuristic vision was inspired by premodern Japanese arts. As Zatlin copiously documents, artists that might have influenced Beardsley included Katsushika Hokusai, Kitagawa Utamaro, and Suzuki Harunobu, the eighteenth-century masters famous for their ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Paradoxically, the novelty of Beardsley’s imagination, what was considered in the Victorian period as “original” and “queer,” was built upon his ideas about “Old Japan.” What underlay Beardsley’s Japonaiserie, then, was an obsession with oriental premodernity.

Such a turn toward oriental premodernity embodied a kind of queer temporality—he was looking backward at a pivotal moment when Victorians were moving forward, confronting their fears of the advent of a new age at the turn of the century. Importantly, the queerness of this temporal logic was also a racialized product, since part of the Victorian anxiety about the future stemmed from theories of racial degeneration. As Elaine Showalter notes in her seminal study on the fin de siècle, “racial boundaries were among the most important lines of demarcation for English society; fears not only of colonial rebellion but also of racial mingling, crossbreeding, and intermarriage, fueled scientific and political interest in establishing clear lines of demarcation between black and white, East and West.”10 In many ways, Beardsley’s Japonaiserie formed a counterpoint to nineteenth-century racial science, which attempted to establish racial categories and, through that very process, the superiority of the European race. In particular, the nineteenth century was an important period when East Asians underwent a new process of racialization and, according to Michael Keevak, became the “yellow race” in European anthropological and scientific discourses.11 Beardsley’s anachronistic arts, which turned European subjects into orientalized figures, constituted a “backward” logic of racialization, disrupting the linear narrative of evolution that nineteenth-century racial theories supported. Tracing contemporary reception of Beardsley, Marillier observes that a common complaint about his works was their “anachronisms,” and how the artist “was quite indifferent to what may be called the dramatic or historical unities.”12 What further disturbed Victorian society, however, was not simply a disrespect for “historical unities,” but how such a disrespect implied a future of racial degeneration, vividly embodied by Beardsley’s orientalized European figures.

There was yet another layer of racialization in the decadent imagination of the Orient. The French decadent tradition through which Wilde’s Salomé was first conceived pointed to the complicated structure of racial figuration in Beardsley’s arts. The decadent movement, after all, was first introduced to England through France, and much of Wilde’s conception of decadence came from French literary works. Similarly, Beardsley’s adaptation of “the Japanese grotesque” was mediated through eighteenth-century French arts; specifically, the Rococo style. As Rachel Teukolsky argues, Beardsley’s illustrations demonstrate “some ideological connections between these two very different cultures and times.”13 The convergence of oriental and continental European queerness might appear counterintuitive; yet, similar to early modern Italy, nineteenth-century France embodied varied concepts of moral corruption and transgression to the English. With the continued association between sodomy and Catholicism, France became another site of religious and racial alterity in the Victorian imagination. Beardsley’s remapping of Japan, then, revealed a transnational trajectory of racial queerness, where the turn toward the Orient was routed through continental Europe in the first place. Ultimately, the most transgressive aspect of Beardsley’s decadent vision was perhaps not his obsession with oriental queerness, but how such a form of racial otherness was always already part of “western” subjectivity.

Endnotes

- Samuel Yamashita, “The ‘Japanese Turn’ in the Art, Architecture, and Cuisine of Europe and America, 1880-2020” (lecture, the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, February 21, 2023).

- Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1979), 1.

- Grace Elisabeth Lavery, Quaint, Exquisite: Victorian Aesthetics and the Idea of Japan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), x, original emphasis.

- Ibid., ix.

- Susan Meyer, Imperialism at Home: Race and Victorian Women’s Fiction (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996), 64.

- W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, The Complete Annotated Gilbert & Sullivan, ed. Ian Bradley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 629.

- Carolyn Williams, Gilbert and Sullivan: Gender, Genre, Parody (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 257.

- H. C. Marillier, Introduction to The Early Work of Aubrey Beardsley (London: John Lane, the Bodley Head, 1899), 13.

- Linda Gertner Zatlin, “Aubrey Beardsley’s ‘Japanese’ Grotesques,” Victorian Literature and Culture 25.1 (1997): 88-89.

- Elaine Showalter, Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture at the Fin de Siècle (New York: Viking, 1990), 5.

- Michael Keevak, Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011).

- Marillier, Introduction, 13.

- Rachel Teukolsky, “On the Politics of Decadent Rebellion: Beardsley, Japonisme, Rococo,” Victorian Literature and Culture 49.4 (2021): 652.

Paris Shih is a Taiwanese writer and cultural critic based in New York. He is the author of The Power of the Badgirl: The Rise of Postfeminism in Popular Cinema (2015), The Girl Revolution: 100 Years of Girl Culture from Flappers to Girl Power (2016), and Sex, Heels, and Virginia Woolf: A History of Feminist Polemics (2018). Currently he is working on a book, Queer Historiography: How to Do the History of Queerness, a dissertation, The Other Sodomites: A Prehistory of Racial Queerness, and a memoir, Divafication. He teaches at Queens College and lives in New York City.

Paris Shih is a Taiwanese writer and cultural critic based in New York. He is the author of The Power of the Badgirl: The Rise of Postfeminism in Popular Cinema (2015), The Girl Revolution: 100 Years of Girl Culture from Flappers to Girl Power (2016), and Sex, Heels, and Virginia Woolf: A History of Feminist Polemics (2018). Currently he is working on a book, Queer Historiography: How to Do the History of Queerness, a dissertation, The Other Sodomites: A Prehistory of Racial Queerness, and a memoir, Divafication. He teaches at Queens College and lives in New York City.