For more than six decades, Saul Steinberg (1914–1999) tackled themes of immigration, identity, war, and other complex issues in humorous yet insightful illustrations for acclaimed publications like The New Yorker. Drawing on his experiences as a Jewish Romanian immigrant who had fled to the United States from Italy at the onset of World War II, Steinberg’s unique perspective and artistic language quickly established him as one of the most renowned cartoonists of the twentieth century. Steinberg’s legacy is great but complicated, and women were perhaps one of his most contentious subjects. While looking at the extensive collection of Steinberg drawings at the Morgan, I was struck by the diversity of his characterizations of women. The drawings Three Liberties (1949), Women (1950), Untitled (Nine ages of woman/square (1960–65), Summer Mask (1960), and Untitled (Drawing Table) (1950), reveal Steinberg’s perception of women simultaneously as performers of New York bourgeois excess, symbols of a society obsessed with masking their emotions, and objects of his love and lust. Despite these often explicitly sexist caricatures, Steinberg’s notion of performing femininity engages in an interesting dialogue with burgeoning feminist ideas about the social construction of womanhood.

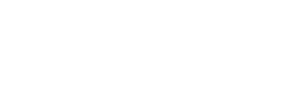

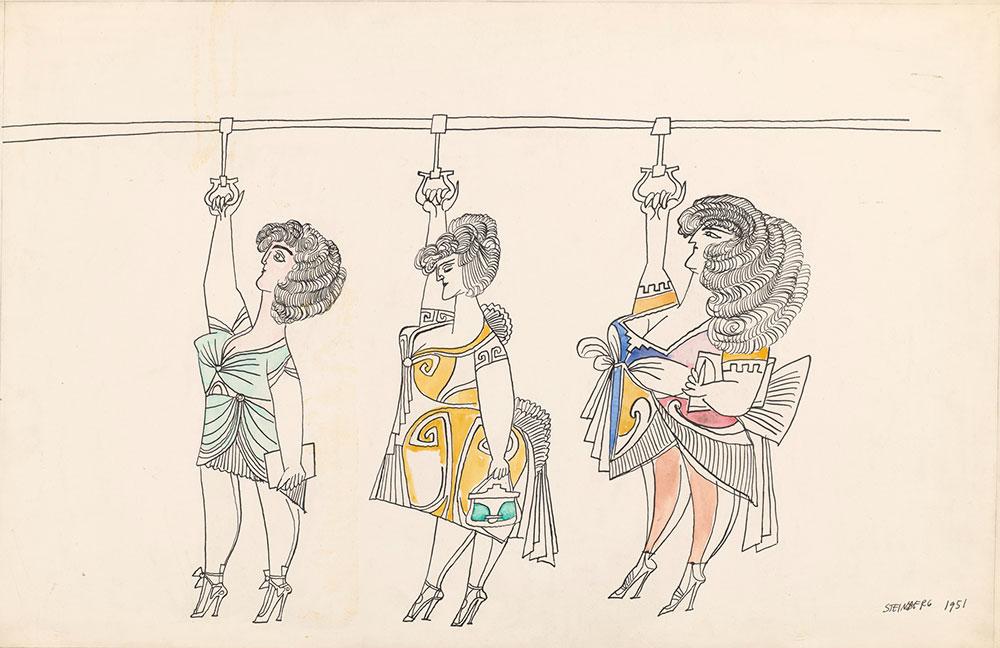

Both Three Liberties and Women depict a group of women dressed in gaudy outfits, sporting elaborately coiffed hair and moving apathetically through the city. In Three Liberties, the grandeur of the women’s ruffly, pastel dresses is moderated by the unglamorous, sparse subway setting, which is only discernible through the grab handle that the women grip. These caricatures of the Statue of Liberty—the subway handles replace Lady Liberty’s torch—and America’s higher virtues are diminished by their participation in the rat race of city living. Similarly, the subjects of Women sport luxurious outfits complete with fur jackets, lace veils, feathery hats, and stilettos. On their own, each woman is a beacon of bourgeois decadence; however, by presenting them as a horde, carrying similar bags and rendered in the same expressive line, Steinberg lampoons the women’s self-perceived individuality. The artist seems to argue that by wearing the latest expensive designs, these women ironically become part of an overly decorated mass rather than distinguishing themselves. The juxtaposition of the women’s attire with the mundanity of their respective situations highlights the theater of their behavior. These satires of women’s intricate self-presentation are a recurring theme in Steinberg’s drawings. In other works such as Two Fighting Women (1945) and Fur Coats (1951) in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, Steinberg contrasts paradigms of conspicuous consumption with uncouth violence and cracked sidewalks.1

Steinberg was deeply interested in the appearance of American women, specifically wealthy New Yorkers. The artist stated that when he first came to America, he was “impressed by those great armies of women with flowers and feathers in their hats.” He posited that since there was no tradition of professional prostitution in America as there was in Europe, honest women did not “have to dress like honest women,” and a “sexy outfit” did not define one’s profession.2 This perceived cultural difference may explain why Steinberg saw American women as the embodiment of all the “panache, appetite, and self-regard of their era.”3 Even though they were afforded more freedom to adorn themselves than their European counterparts, the socialite was still dissatisfied, much to Steinberg’s fascination. In his records, Steinberg had clipped a New Yorker’s letter to a tabloid that shared his sentiments, which reads, “The average woman, young or old, seems to walk around New York with her head held high, jaw firmly set, eyes blazing and nostrils flaring. Her fists are usually clenched, and she seems to be just itching for a fight with members of either sex. Why is this?... Why aren’t you all happy? Don’t you know being a female in this great country of ours is the sweetest racket there is?”4 Besides the blatant ignorance of patriarchal oppression present in this quote, Steinberg’s unsympathetic parody of the American woman’s relationship with consumer culture was also in line with conservative panic in the 1950s about the increasing conformity of society, a phenomenon that was seen as distinctly feminine in nature and lambasted for causing a crisis in masculinity.5

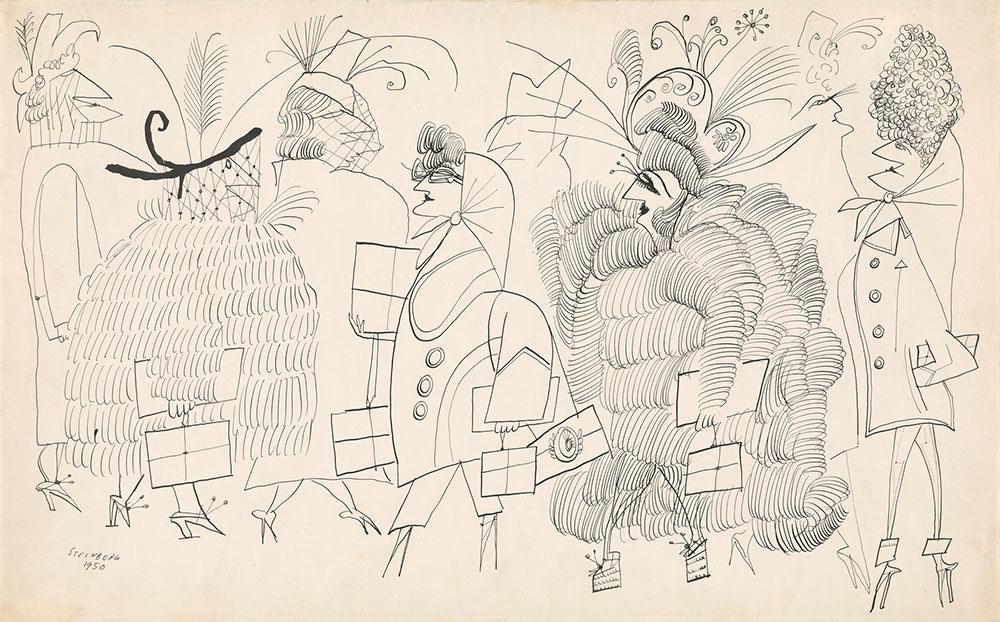

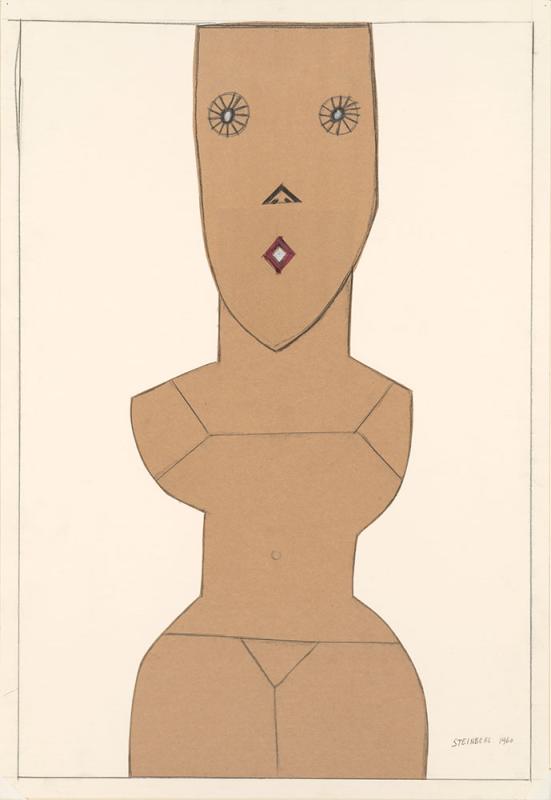

In Untitled (Nine ages of woman/square) and Summer Mask, Steinberg shifts his attention from women’s clothing to their facial features, recalling the geometric physiognomic language present in Steinberg’s mask-making practice. Steinberg began making masks in 1959 and continued to create them prolifically until 1962.6 Drawing on, cutting into, and gluing together brown paper bags, Steinberg constructed elaborate facial expressions, often complete with makeup, hair, and, as seen in Summer Mask, even a body. He would wear these masks in public to be photographed, as well as with his friends at parties.7 Steinberg’s creation of and performance with these masks played into his larger beliefs about how emotions are stigmatized in organized society. Due to this restriction, masks are worn by everyone to protect “against revelation” and present a consistent and appropriate façade in public situations.8

Steinberg’s depictions of women in this style were particularly coded in rhetoric. According to Steinberg, the historical scarcity of women in America dating back to the colonial era caused them to be transformed into a “goddess image.”9 However, this deification also had the adverse effect of presenting women as statues, a characterization that had been reinforced by women themselves through the widespread use of corsets and girdles from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Women could not only render their bodies still with boned armament, but they could also transform their faces into “static elements that will not express emotions,” just like a mask.10 Steinberg echoes and elaborates on this belief in a rare, filmed interview, in which he states that when women “are in society… they put on a constant expression. They have invented this rectangular smile. They have invented the octagonal or the several other geometric forms of mouths and eyes and so on, and it’s a steady mask representing amusement, happiness, contentment… They don’t want to appear that there is something else besides this very little bit that they give, this 1% or less of their personality, and this is their public appearance; this is their political mask.”11 Interestingly, Steinberg continues by lambasting the modern woman’s mask, mourning the days when women’s masks would imitate “nature” and “art” rather than “photography.” He believes mimicking fashion magazines reduces women to “four or five types only,” a disgrace to the “variety in the world.”12

Steinberg’s distaste for the mask of modern society underpins the forms used in both Nine ages of woman/square and Summer Mask. Although Nine ages of woman/square is not intended to be a mask (in fact, it was published in Steinberg’s fifth compilation of illustrations The New World), it still adheres to the mask style. As the woman ages, she develops the classic “rectangular smile” and “geometric forms of mouths and eyes” before reverting to her original appearance. Despite differing makeup techniques which transform the shape of her eyes and lips, the woman remains completely expressionless throughout the phases of her life, concurrent with Steinberg’s idea of the static mask. The consistency in her facial structure, which is made especially apparent by the guiding grid lines and the return to simplicity in the last face, highlights the falsity of her accessories and makeup. This sense of transience, combined with the outlandish, garish, and even comical nature of the adornments, may relate to Steinberg’s criticism of women’s allegiance to fashion magazines. The cartoonist strikingly does not manipulate the nose throughout all nine phases. In the interview cited above, Steinberg explains that the nose is the most “eloquent” and “antisocial” part of the body, revealing “exactly who we are” because it is difficult to change, unlike the eyes and the mouth.13 The tiny, upturned triangle nose seen in Nine Ages of woman is considered distinctly American, with Steinberg stating that the “essential thing of the American mask is the disappearance of the nose.”14 By reducing the most honest part of the face to a minuscule shape, Steinberg implies that America and its people are shrouded in artifice.

Summer Mask shares the same nose as, but has a different expression than, the figures in Nine ages of woman/square. Gesturing towards a similar mask in a filmed interview, Steinberg refers to the face, which is composed of a diamond mouth, shining eyes, and the quintessential American nose, as a “leering teenager who imitates comic strip characters.”15 Made in the same summer that Steinberg met and began seeing twenty-four-year-old Sigrid Spaeth, a woman half his age, this mask of an American teenager could be a meditation on his young lover’s status. Spaeth was a recent immigrant from Germany who may have adopted a mask to assimilate into her new environment. The distinctly sexualized nature of Summer Mask would also support this interpretation. Unlike other Steinberg masks, the head is attached to a curvaceous, barely clothed body, which, in turn, subverts the expression of the mask. If she is a teenager leering at us, the inclusion of her almost-nude form also asks us to leer at her. Perhaps this reciprocal, lustful exchange was meant to reflect Steinberg and Spaeth’s relationship, with Steinberg acknowledging the inappropriate nature of his attraction by describing it as “leering.” It is important to note that Steinberg’s linking of masks, especially those that lack an “honest” nose, to women plays into age-old stereotypes about feminine duplicity.

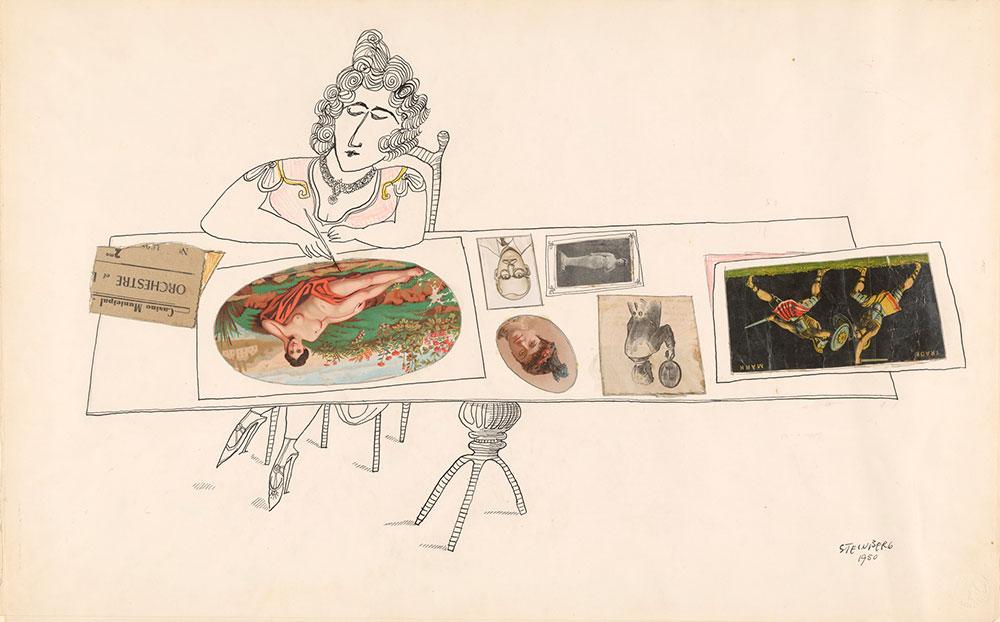

In Untitled (Drawing Table), Steinberg drastically shifts his characterization of women as masters of artifice, instead presenting his wife, Hedda Sterne, at work. In this piece, Steinberg humanizes his subject and even engages in an exploration of women’s self-reflexivity using a careful selection of collaged material. Sterne, recognizable through her distinct hairstyle, is depicted seated at a table and painting a reclining nude while surrounded by an assortment of clipped images. Steinberg’s choice to portray his wife calmly rendering a subject often understood as the embodiment of the objectification of women throughout art history is not a random one. Sterne, a renowned Abstract Expressionist despite the movement’s domination by men, is implied to be reimagining and carving out a place for herself within the sexualizing artistic tradition, grappling with the discrepancy between her womanhood and the one found in museums and publications. This narrative is reinforced by the other paper scraps on the table. The full-body black and white photograph and the bust represent other ways of depicting women in art history. Given the similarities of the hairstyle and necklace worn by Sterne to those in the oval portrait, this image may also correlate with Steinberg’s theories on women imitating fashion magazines. The man pondering his own reflection is a clear indication of the piece’s contemplative quality, and the sparring soldiers could be a visual manifestation of Sterne’s internal conflict. The French newspaper scrap at Sterne’s right references the iconic motifs of Cubist collages, firmly situating the piece in conversation with the art-historical canon.

Perhaps the most telling collage piece is the self-portrait of Steinberg himself. Steinberg nurtured a life-long fascination with collage, relating it to his childhood in Romania, which he referred to as a “college for collages.”16 Steinberg’s personal connection with and appreciation for the medium may correlate with the intimate, reflective nature of the experience captured in Drawing Table, and this element of projection is made visible through his self-portrait. The inclusion of Steinberg’s own visage could also be an homage to his relationship with Sterne. Placed carefully by her side and facing her like family photos on an office desk, the composition is even somewhat romantic. Steinberg met Sterne in 1943 and was instantly infatuated with her.17 They married in 1944 and had a tumultuous but passionate relationship before they amicably separated in 1960. Despite the ending of their romance, the pair spoke to each other nearly every day, and Sterne remained Steinberg’s close friend, confidante, and legal wife until his death in 1999.18 The divergence here from Steinberg’s typical depiction of women can perhaps be attributed to the affection the artist held for his partner at the time, rather than any substantive, feminist leanings.

I propose this reading of Drawing Table because, as evidenced by earlier analysis, Steinberg was known to be a sexist. Besides the negative portrayal of women in his drawings, despite his marriage to Sterne and thirty-five-year-long relationship with Sigrid Spaeth, Steinberg was an unrelenting flirt whose numerous extramarital affairs resulted in significant strain on his interpersonal connections. Sterne herself compared her husband to the male characters of D.H. Lawrence, or “misogynists who are unable to love women freely and completely,”19 and even described herself as Steinberg’s “Elaine [de Kooning] who protected Bill from ever having to marry any of his women.”20

Although Steinberg cannot be considered a proponent of gender equality by any means, his notion of the performance of womanhood has a fascinating correlation with burgeoning theories of second-wave feminism, specifically the distinction between gender and sex. In postwar America, the prominence of sociology and anthropology had led to a dominant, biologically based view of gender, wherein women’s behavior was seen to be heavily determined by maternal instinct.21 The American public was shocked by Simone de Beauvoir’s seminal text, The Second Sex, which was translated and distributed in the United States in the mid-1950s. Although the theory of socially constructed gender had existed since the early twentieth century, de Beauvoir revitalized its argument for a new audience, arguing that “female biology was a ‘situation’ which could be freely interpreted” and that women’s inferiority stemmed only from “society’s interpretation of woman’s biology and maternity, not from any fixed part of the biology itself.”22 This countercultural perspective was echoed by American sociologist Mirra Komarovsky, whose 1953 book Women in the Modern World: Their Education and Their Dilemmas argued that “women’s economic, legal, psychological, and political positions were not derived from biological fact but were largely the result of social fiction.”23 Steinberg inadvertently echoes this perspective with his emphasis on women’s constructed identity and his repetition of archetypes in works like Three Liberties, Women, and Summer Mask. In Nine ages of woman/square, one could even argue that the first stage, marked by a lack of hair, clothing, makeup accessories, and a neck, represents a genderless being before the indoctrination of society. Drawing Table, in turn, elucidates how visual culture reinforces social fictions of womanhood and how women, especially female artists, can negotiate this narrative.

This discrepancy between Steinberg’s personal views and artistic themes could be explained by his unique status as an artist who earned most of his income through magazine contributions. In the words of Harold Rosenberg, Steinberg was unusually “conscious of his audience, both the worldwide general public, whom most artists tend to ignore, and the gallery-going public, which is the social core of the art world.”24 Thus, the tenuous connection between Steinberg’s drawings of women and the ideas of second wave feminism may reveal an underlying spirit that is increasingly aware of the artifice of not just mass media, but of the very underpinnings of 1950s and 60s society.

Jacqueline Yu

Souls Grown Deep Foundation Intern in the Modern and Contemporary Drawings Department, 2022–23

Undergraduate Student at Columbia University in the City of New York

Endnotes

- Chris Ware and Mark Pascale, Along the Lines: Selected Drawings by Saul Steinberg (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), 9.

- Ian Frazier, “Introduction,” in Steinberg at The New Yorker, ed. Joel Smith (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2005), 146.

- Joel Smith, Saul Steinberg: Illuminations (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 104.

- Ibid.

- Anna Lebovic, “‘How to be in Fashion and Stay an Individual’: American Vogue, the Origins of Second Wave Feminism and Mass Culture Criticism in 1950s America,” Gender and History 31, no. 1 (March 2019): 179.

- “Paper-bag Masks,” The Saul Steinberg Foundation.

- Smith, “Saul Steinberg,” 150.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Saul Steinberg Talks (1967),” YouTube video, 15:50 to 17:37, posted by “Garramedia,” August 28, 2013.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 19:07 to 19:37.

- Ibid, 18:00 to 18:23.

- Ibid, 18:27 to 19:07.

- Andreas Prinzing, Saul Steinberg: The Americans (Koln, Germany: Koln Snoeck, 2013), 25.

- Deirdre Bair, Saul Steinberg: A Biography (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2012), 95.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 246.

- Charles Simic, “The Loves of Saul Steinberg,” The New York Review, December 20, 2012.

- Rosie Germain, “Reading The Second Sex in 1950s America,” The Historical Journal 56, no. 4 (2013): 1041–1062.

- Ibid, 1056.

- Shira Tarrant, “When Sex Became Gender: Mirra Komarovsky’s Feminism of the 1950s,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 33, no. 3 (Fall–Winter, 2005), 339.

- Harold Rosenberg, Saul Steinberg (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978), 33.