This post was created by Shaoyi Qian Sherman Fairchild Fellow Thaw Conservation Center.

Figure 1: Detail of Southwark Fair, 1733. The Morgan Library & Museum, Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987; PML 146852.9.

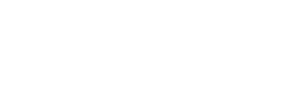

The city street in eighteenth-century Europe was a bustling place with crowds, merchants and all sorts of entertainment, among which was the peepshow. A peepshow involved a box with at least one viewing hole, through which a series of images, spaced sequentially, could be seen. Such boxes were carried around by the showmen who were also the narrators, offering a more interesting experience. For people back then, these boxes were portals to distant landscapes, foreign continents, or battlefields. A depiction of the peepshow can be found in the lower right corner of this 1733 print by William Hogarth of the Southwark Fair (PML 146852.9, Figure 1).

Soon, miniaturized versions of the peepshows were produced as parlor entertainment. Their format diversified over the centuries and their names differed depending on the regions, such as “teleorama”,”‘expanding views”, or “tunnel books”. In this blog, I will use the more universal term “paper peepshows”.

As the Sherman Fairchild Fellow in Conservation, I worked with Pine Tree Conservation Fellow Yungjin Shin to conduct a survey of the Morgan’s collection of games and toys to assess and improve their storage and housing. This survey has offered me the opportunity to examine the paper peepshows at the Morgan as a group. It is a delight to find that, though small in quantity, they constitute a broad spectrum of the typical formats of paper peepshows from eighteenth-, nineteenth- and twentieth- century Europe and North America.

Eighteenth-century paper peepshows

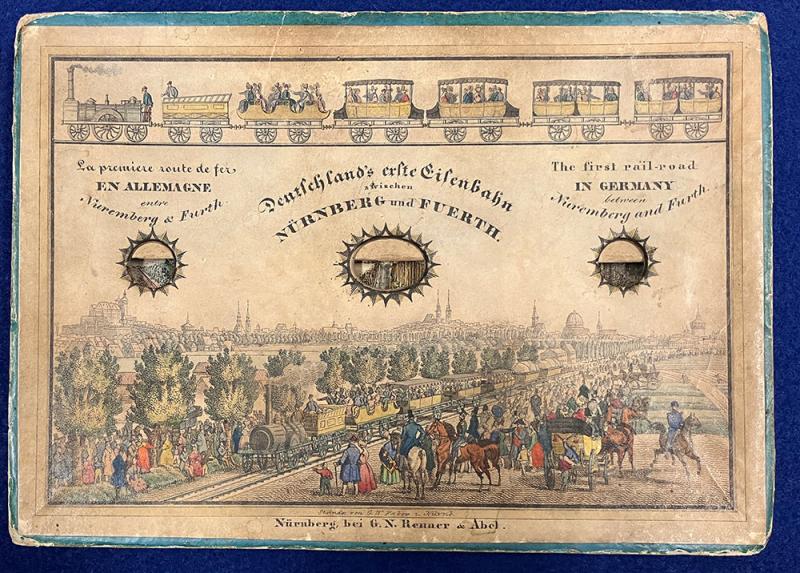

Figure 2: Indication of the royal privilege “C. P. Maj” in the lower left corner of the cut-out panels of [Die] B[uch-] B[inderei], published by Engelbrecht between 1730 and 1750. The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased on the Harper Fund, 1996; PML 127773.

All the eighteenth-century paper peepshows in the Morgan’s collection are by Martin Engelbrecht (1684–1756), a German engraver and publisher. He was granted a royal privilege that forbade the unauthorized copying of his peepshows between 1719 and 1739, which may explain the little evidence of similar productions by other publishers from this time period (Figure 2).

Engelbrecht’s peepshows usually consist of six to eight panels of hand-colored intaglio prints pasted onto thicker paper. The blank areas in the panels, with the exception of the backdrops, are meticulously cut out. Like their precursor, Engelbrecht’s peepshows are supposed to be arranged in a front-to-back sequence in a table-top sized viewing box. With the right spacing, together, they offer a complete view with the illusion of depth.

Engelbrecht published his peepshows in three standard sizes: small (approx. 73 x 90 mm), medium (approx. 90 x 140 mm) and large (approx. 180 x 220 mm). I was able to find examples of each size in the Morgan’s collection (Figures 3, 4, 5, 6). The typical subjects of Engelbrecht’s peepshows include biblical scenes, aristocratic entertainment, theatrical stage, and daily life scenes such as interior spaces and depictions of different occupations. Although our impression of paper peepshows today is that they are children’s toys, Engelbrecht’s paper peepshows were most likely intended for adults, especially from the middle and upper classes.

Figure 3: The three standard sizes of Engelbrecht’s peepshows.

From left to right: [Panduren-Exercitien in ihrem Lager]. The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased on the Elisabeth Ball Fund, 2011; PML 87371.1-7.

[Bibliothek]. The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased on the Elisabeth Ball Fund, 2015; PML 88580.

Set no.2 from [The four seasons]. The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Julia P. Wightman, 1991; PML 88501.1–4.

Peep

Peep

Figure 4: Small format.

Set no.2 from [The four seasons]. The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Julia P. Wightman, 1991; PML 88501.1-4.

Peep

Peep

Figure 5: Medium format.

[Bibliothek]. The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased on the Elisabeth Ball Fund, 2015; PML 88580.

Peep

Peep

Figure 6: Large format.

[Panduren-Exercitien in ihrem Lager]. The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased on the Elisabeth Ball Fund, 2011; PML 87371.1–7.

Nineteenth-century paper peepshows

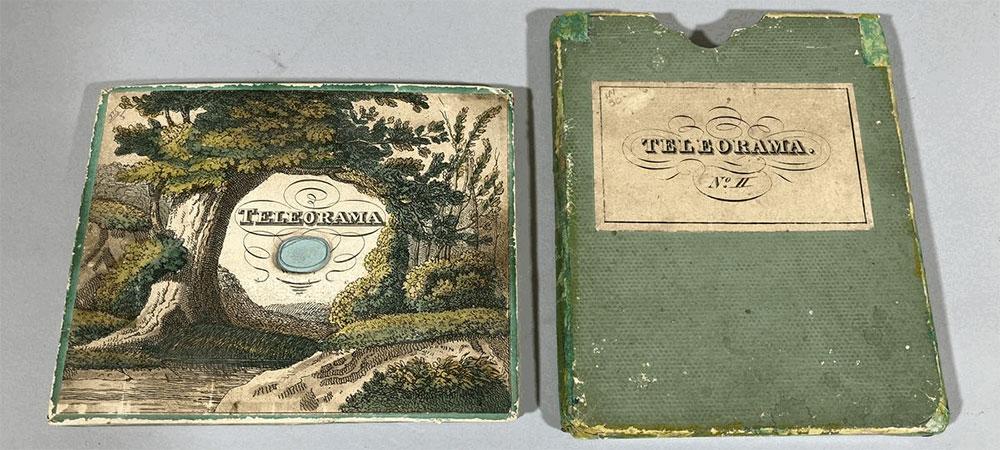

Around the 1820s, paper peepshows started to take on the accordion-folding format that we are more familiar with today. The panels are connected with paper or textile accordions, called the “bellows.” It is not known who invented this new format, but Heinrich Friedrich Müller, a Vienna-based publisher, art and book dealer, has been associated with its first appearance in Europe. Starting in 1824, Müller published a series of paper peepshows, which he called “Teleorama.” These teleoramas consist of 5–6 cut-out panels, a front-face and a back-scene, housed in slip-cases. The prints were hand-colored etchings and later lithographs. The Morgan has No.II from this series (Figure 7).

Peep

Peep

Figure 7: Teleorama No.II, with its original slip-case on the right. The Morgan Library & Museum, Bequest of Julia P. Wightman, 1994; PML 150808.

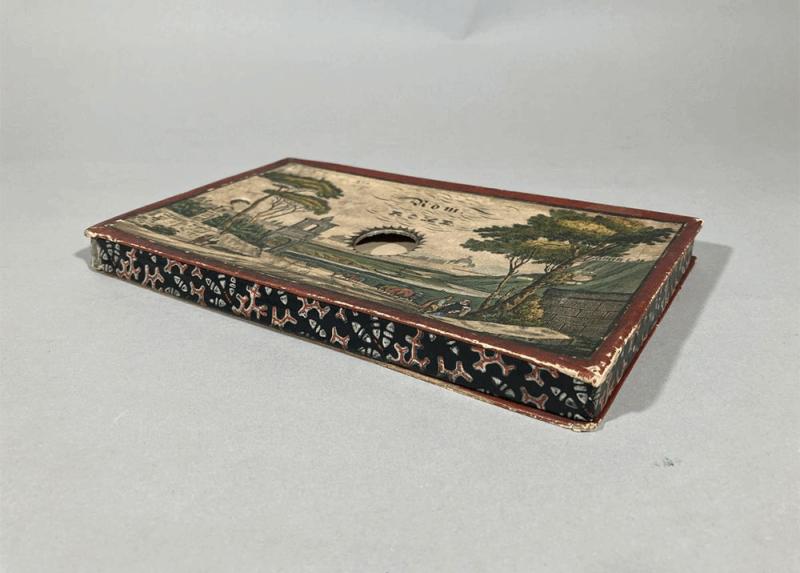

The format of the nineteenth-century paper peepshows is largely uniform. Variations usually lie in the number of peep-holes, the position of the bellows, the shutters, and whether or not it is in a cartonnage (Figures 8, 9, 10, 11, 12). “In a cartonnage” means that the lid and the floor of the shallow box are the front-face and the back-board of the peepshow. To view it, one just has to lift the lid of the box to extend the peepshow.

Peep

Peep

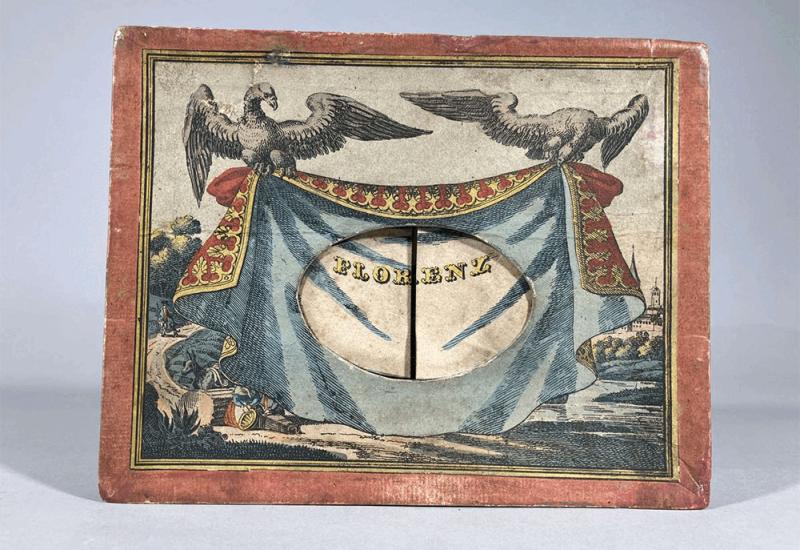

Figure 9: An example of peepshow in a cartonnage and its bellows being on the sides.

Rom. The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Julia P. Wightman, 1991; PML 88519.

Peep

Peep

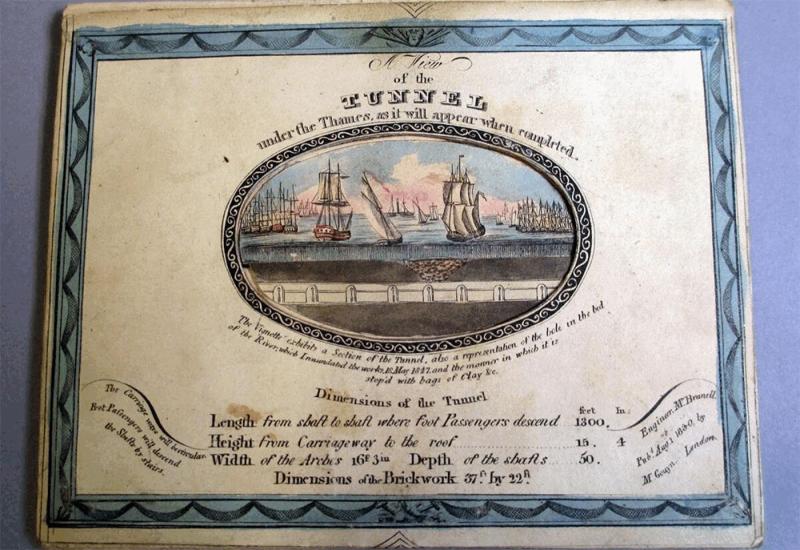

Figure 10: A view of the tunnel under the Thames, 1830. The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Julia P. Wightman, 1991; PML 88506.

Peep

Peep

Figure 11: Florenz. The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Julia P. Wightman, 1991; PML 88514.

When a peepshow is closed, the bellows fold in behind the peep-hole. To hide the blank paper of the bellows showing through the peep-hole, painted images (“shutters”) were adhered to the bellows at those spots. When the peepshow is extended, the shutters retract. Depending on the position of the bellows, the shutters can be horizontal (PML 88506, Figure 10) or vertical (PML 88514, Figure 11).

Peep

Peep

Figure 12: Le Palais Royal. The Morgan Library & Museum, Bequest of Julia P. Wightman, 1994; PML 150807.

The materials of the shutters differ depending on the size of the peep-hole. Thicker boards were used for smaller-sized peep-holes as shown here, while paper was used for larger peep-holes.

Peep

Peep

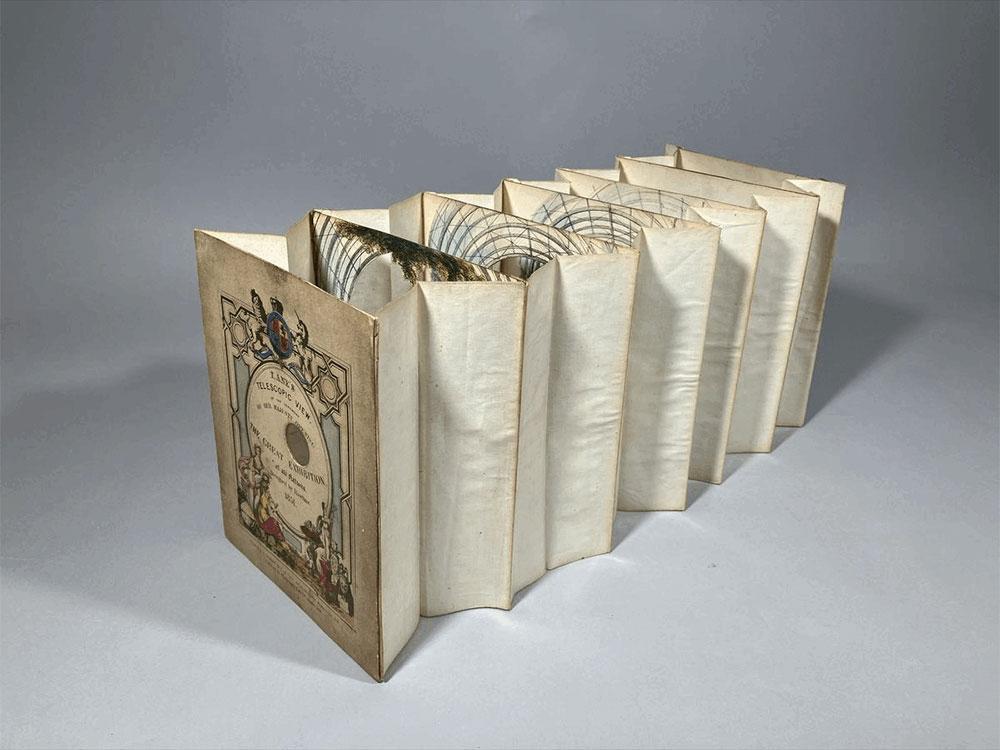

Figure 13: Lane's telescopic view of the ceremony of Her Majesty opening the Great Exhibition, 1851, with a “lens” in the peep-hole. The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Julia P. Wightman, 1991; PML 88509.

Occasionally, the peephole would have a “lens” - a piece of glazing that provides no magnification and thus does not add to the optical effect. I found one such example in the Morgan’s collection (Figure 13).

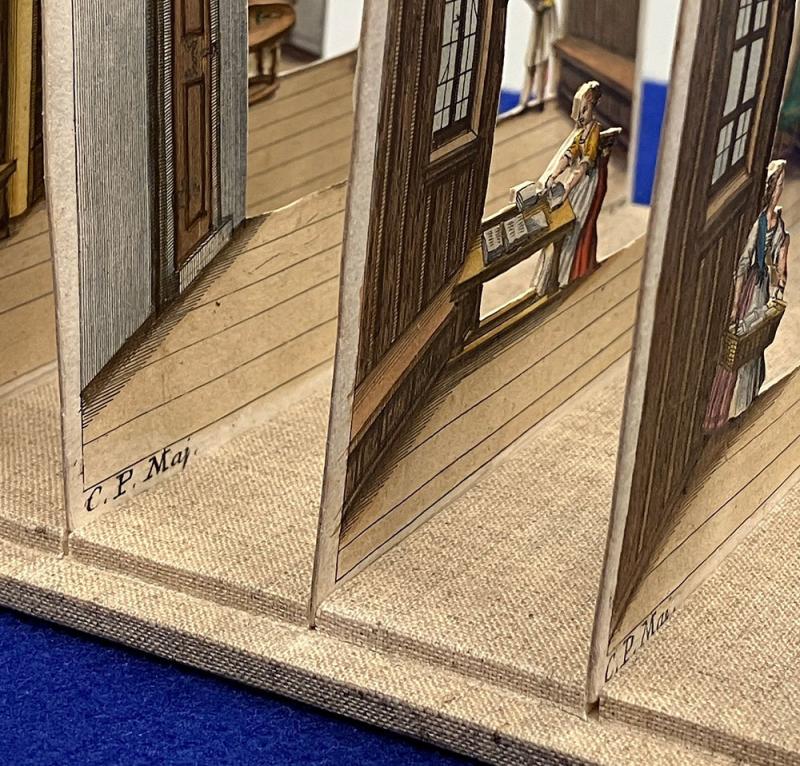

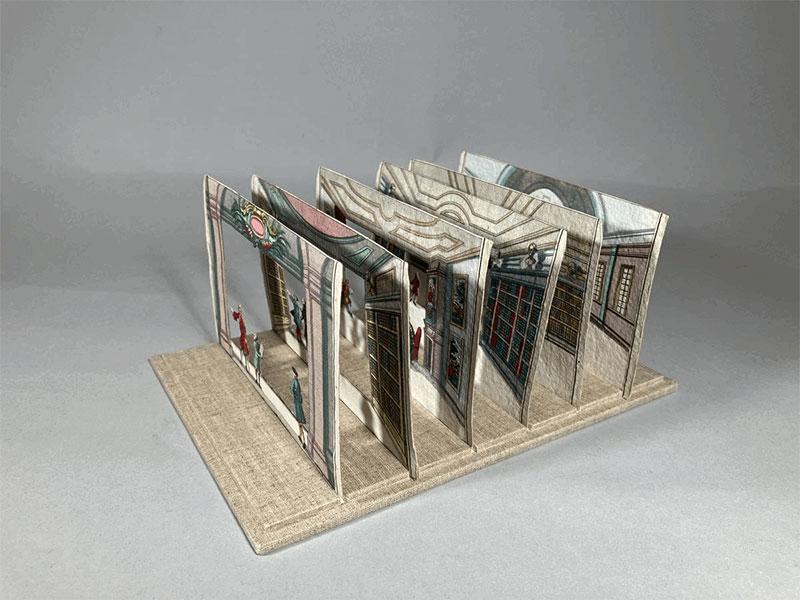

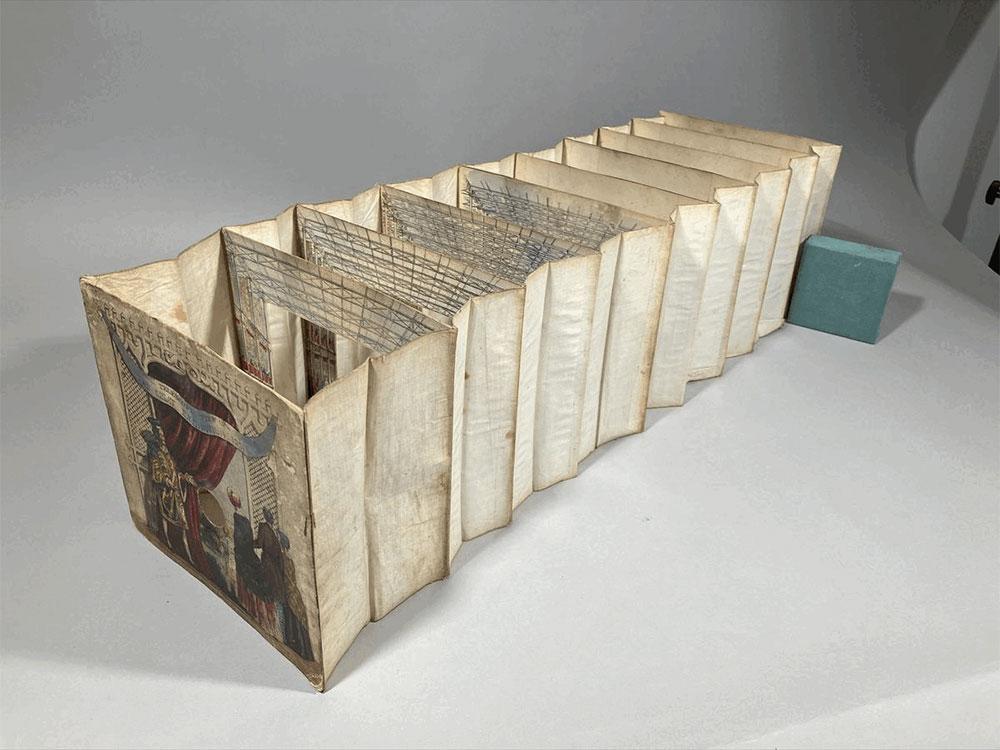

I also found a slight outlier, a table-top tableau, among the accordion-folding peepshows (Figure 14). Its panels are not connected with bellows but each has a wooden stand-up. In a way, this format is a closer descendant to Engelbrechet’s peepshows. Table-top tableaux predated the accordion-folding peepshows and did not entirely fall out of fashion afterwards. They could be in specially-designed wooden boxes that serve as the set-up, or simply have wooden stand-ups. Some table-top tableaux were issued after accordion-folding peepshows with similar designs, like the one at the Morgan.

Peep

Peep

Figure 14: Exposition de Londres, ca. 1851. The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Julia P. Wightman, 1991; PML 88517.

Peep

Peep

Figure 15: Telescopic view of the Great Exhibition, 1851. The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Julia P. Wightman, 1991; PML 88508.

Continuing the tradition of street peepshows, the nineteenth-century paper peepshows offered virtual trips to different landscapes and cityscapes. However, there are two popular subjects unique to the nineteenth century: the Thames Tunnel and the Great Exhibition of 1951. These two industrial feats spurred the production of paper peepshows, as well as other paper ephemera, depicting the Tunnel and the Crystal Palace and sold as souvenirs. You might have already noticed this just from the peepshow examples presented so far (Figure 10: PML 88506, Figure 13: PML 88509, Figure 14: PML 88517). Another example that I would like to include is PML 88508, which used what appear to be mica chips1 to create the sparkly effect of water cascading down the Crystal fountain (Figure 15).

Twentieth-century paper peepshows

Stepping into the twentieth century, the format of mass-produced paper peepshows did not change much. Most of them take on the accordion-folding form. They were still inspired by past or current events, such as the 1953 Coronation of Queen Elizabeth (PML 88510) and the 1939 New York World’s Fair (PML 150114), but we see peepshows most often used in children's illustration books, such as Tomie dePaola's Country farm (PML 86971) and The Nutcracker suite (PML 88516), both published in the 1980s. At the same time, artists have continued to be inspired by paper peepshows and employ this creative format for artists’ books, such as the miniature book Vatican peep, published in limited quantity circa 1985, with design & text by Joseph L. Curren, art & calligraphy by E. Helene Sherman, hand-coloring by Eloise C. Massmann and layout & binding by Robert E. Massmann. The Morgan owns copy no.53.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Balzer, Richard. Peepshows: A Virtual History. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.,1998.

Hyde, Ralph. Paper Peepshows: The Jacqueline and Jonathan Gestetner Collection. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club Ltd, 2015.

Robinson, David. “Augsburg Peepshows.” Print Quarterly 5, no. 2 (June 1988): 188-191.

IMAGES

Shaoyi Qian, 2023, Figures 1–9, 11–15.

Endnotes

- Micas are a group of silicate minerals, some of which appear colorless and transparent. They can be split into thin sheets.

Shaoyi Qian

Sherman Fairchild Fellow Thaw Conservation Center

The Morgan Library & Museum