A prince’s necklace—glistening gold borders and calligraphic découpage

MS M.458.12

This post was created by Yvonne (Bonnie) Hearn, Sherman Fairchild Post Graduate Fellow in Paper Conservation.

The Morgan Library & Museum holds a collection of fifty-seven Persian and Indian album leaves acquired by J. Pierpont Morgan from Charles Hercules Read in 1911. These leaves are collectively known as the Read Albums and are broadly divided into two groups, Persian (MS M.386.1–.21) and Indian (MS M.458.1–.36). Many of the leaves date from the early sixteenth century to the late nineteenth century and are double-sided, depicting miniature paintings on one side and calligraphy on the other . Most of them were once bound in muraqqa's (albums)1. The bound leaves would have been presented in paired openings, two miniature paintings followed by two calligraphic specimens. Decorative rulings and borders would surround the images and complete the design of the leaves. Initially, albums like these were created in workshops, commissioned by emperors and courts as luxury objects detailing events, history, and poetry of the time. Albums were used for intimate viewings, treasured and passed down within royal families, and reformatted as ownership changed.

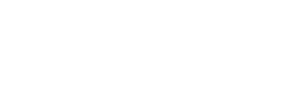

Over the last eighteen months, the Read Album leaves have been examined and undergone conservation treatment in the Thaw Conservation Center. Working closely with these leaves has allowed conservators to better understand the artists’ materials and techniques used in creating these complex works of art. This post will focus on some of the decorative techniques seen on the recto and verso of one leaf in the collection—MS M.458.12r (figure 1), Prince Salim at a jharoka window, and MS M.458.12v (figure 7), A calligraphy by Ali—using technical examination to highlight details beyond the observation of the human eye.

The recto depicts Prince Salīm, soon to become Jahāngīr, future ruler of the Mughal dynasty between 1605 and 1627 (figure 1). The Prince holds a pink rose in one hand and the pommel of his sword in the other while looking out his balcony window.

The Prince’s gaze (figure 2) likely would have met his father Akbar’s reciprocal gaze on a facing leaf. Akbar, the second Mughal ruler (r. 1556–1605), is depicted in a matching folio within the collection, MS M.458.24, Akbar at a jharoka window. Both leaves have highly decorated borders of intertwining floral patterns and gold illumination, suggesting the pair may have been a frontispiece opening to an album2.

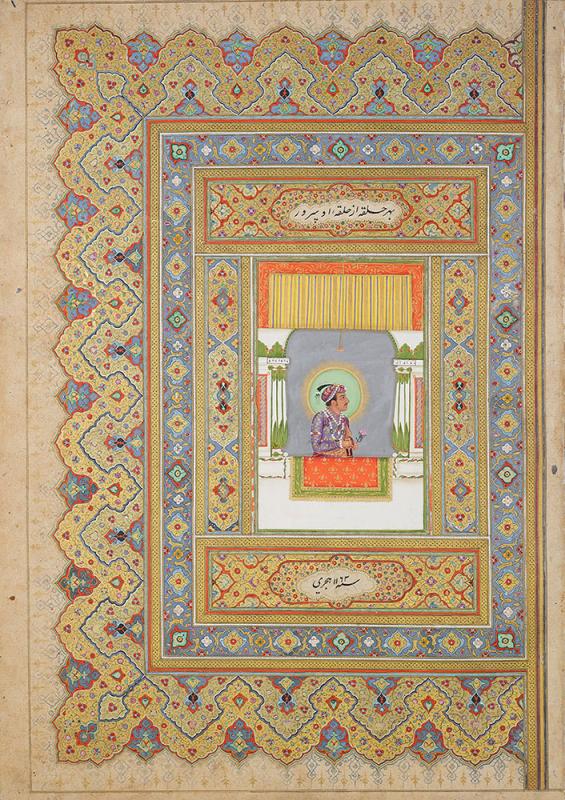

Examining this leaf under a microscope reveals the skill and quality of the artist’s techniques. Under reflected visible light this photomacrograph (figure 3) shows the carefully applied white paint used for the bead-like drops of Prince Salīm’s necklace and the tiny petals of the daisy-like flowers that adorn his purple coat.

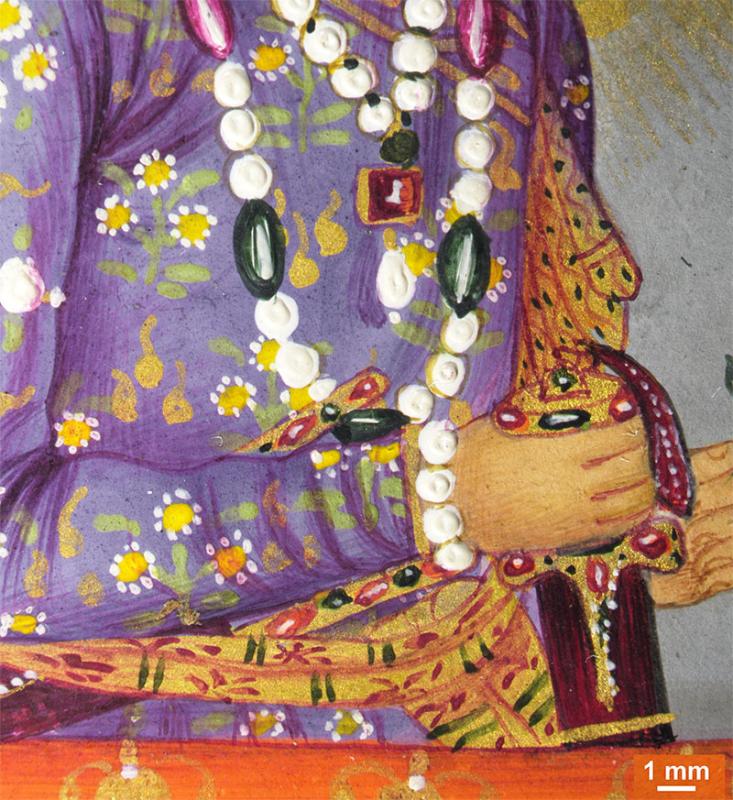

Adjusting the light source to a low, raking angle on one side of the miniature (figure 4) reveals how proud the necklace beads sit on the surface. This demonstrates the artist’s meticulous attention to detail when creating this portrait.

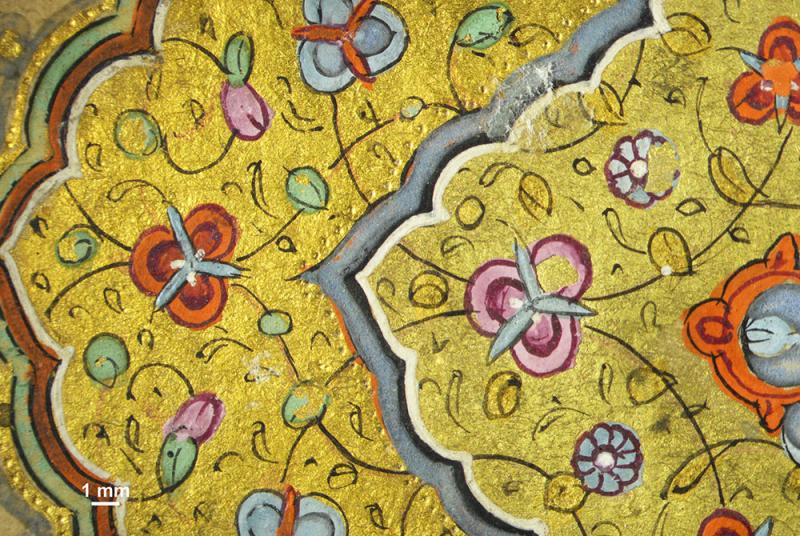

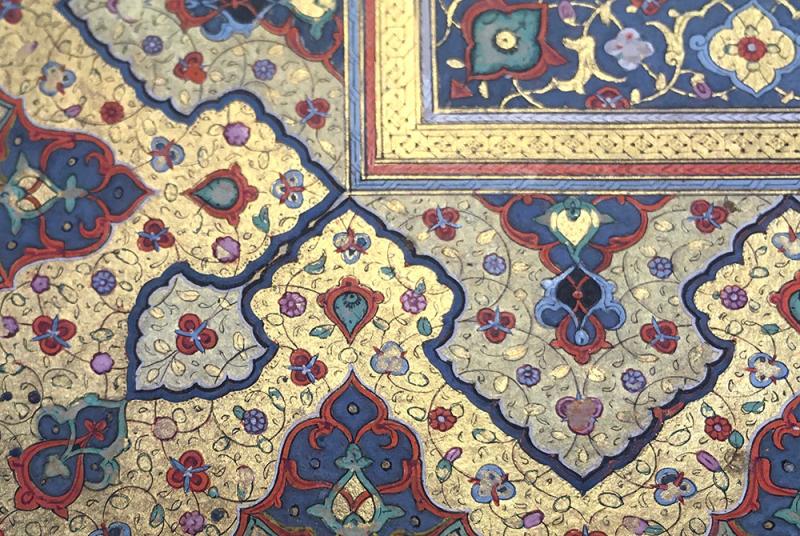

The next photomacrograph shows an area of the ornately decorated borders. Although very subtle in this image, two tones of gold paint were used by the artist; a warm gold tone through the left side and a cool gold tone through the right side (figure 5). This technique utilises the reflective properties of gold paint, creating a variance in lustre and tone. Different tones of gold paint were achieved by Persian artists by adding other metallic pigments, such as copper to make the paint appear warmer or silver to make the paint appear cooler3.

The tonal variance of the gold used on this leaf becomes more distinct under angled light (figure 6). The warm-gold tone is brightly illuminated while the cool-gold tone appears dull with little gold leaves catching the light in contrast. One can imagine how these illuminated borders would have glistened and shimmered in the light as the album page was turned by the reader.

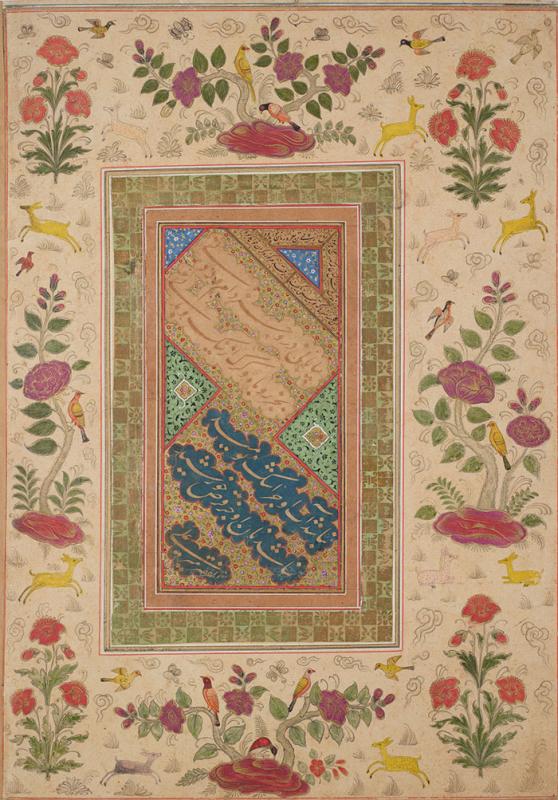

On the verso of this leaf is a calligraphic découpage specimen and the only one of its kind amongst the Read Album leaves (figure 7). Découpage involves the cutting out of paper using a penknife and pasting the pieces onto another sheet to create a paper collage. Both the cut-out pieces and remaining stencil sheet could be used as positive and negative specimens, respectively. This technique dates to the Persian book arts of the fifteenth century and became more prevalently used by calligraphers in the sixteenth century, by which time découpage evolved into its own area of artistic specialization4. When Prince Salīm ruled as Jahāngīr, he encouraged areas of specialization within royal workshops where artists would execute only one aspect of an album, whether it be portrait painting, calligraphy, or illumination5.

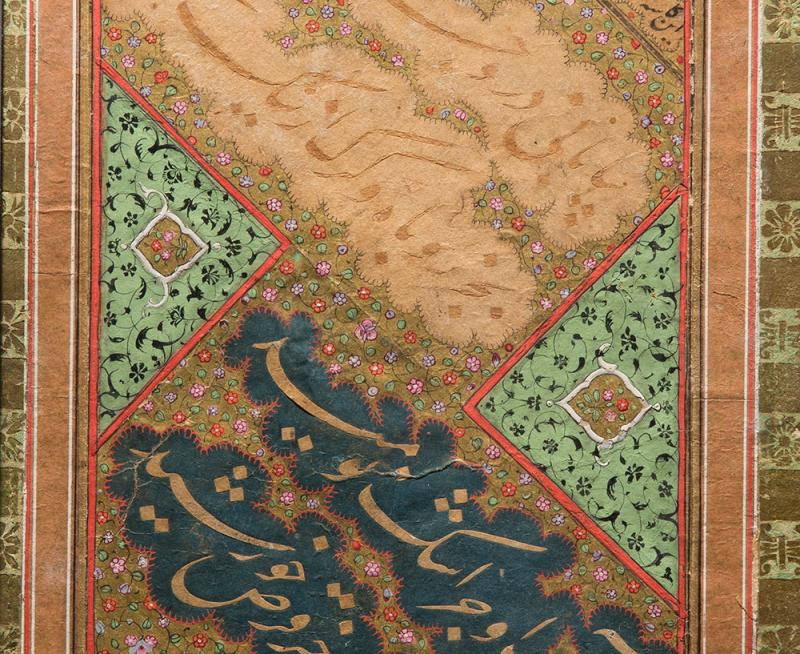

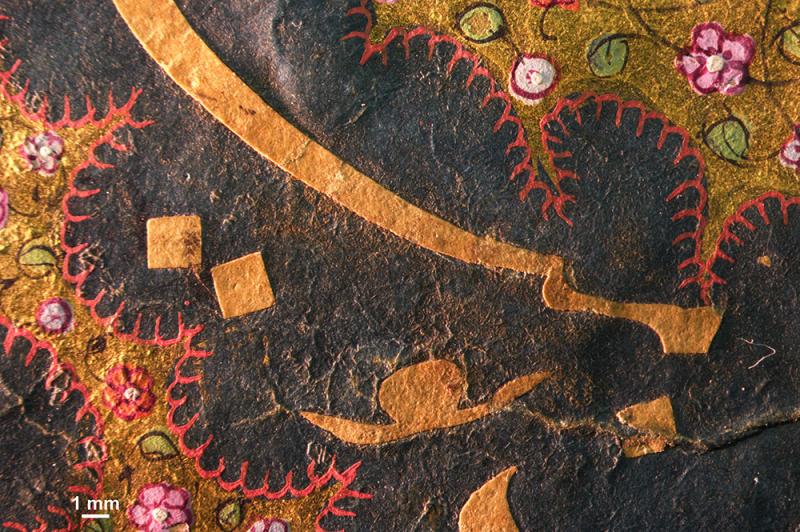

Looking closer at the calligraphy under raking light, you can see both negative and positive elements within the specimen (figure 8).

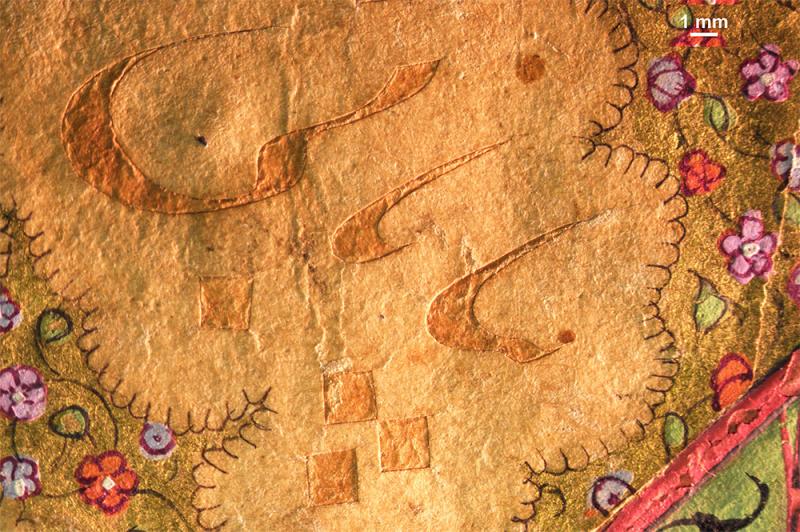

Looking even closer under the microscope reveals that the upper area of calligraphy is negative, meaning that the script was cut from the light cream colored paper to create the negative stencil and the stencil was then adhered on top of a darker tan paper (figure 9).

The photomacrograph in figure 10 shows an example of positive découpage. The lower area of calligraphy is individually cut cream-colored pieces of paper that are adhered onto blue paper.

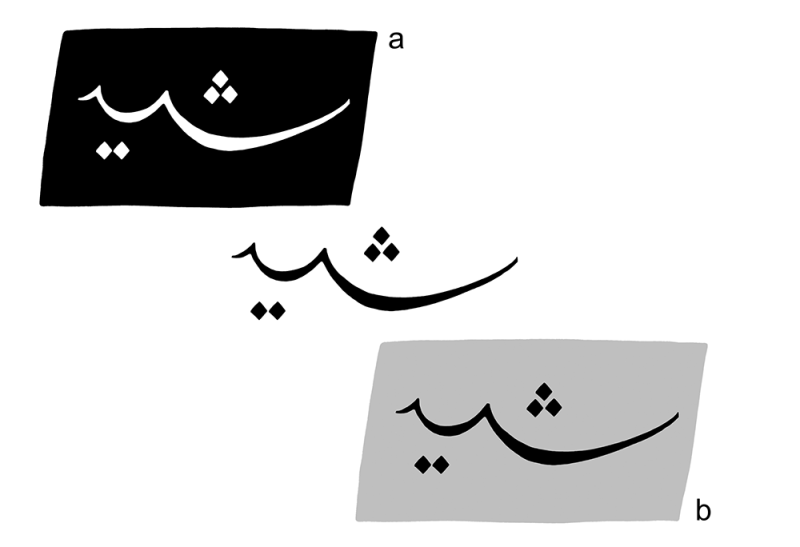

Stages of creating negative and positive découpage specimens is outlined in figure 11. The level of accuracy in creating these delicate cursive- script cut-outs requires the highest level of skill.

The images shared in this post, detailing Prince Salīm’s necklace, illuminated gold borders, and calligraphic découpage, are just a few examples of the many superb, skillful, and artistic elements within the Read Album collection. Additional images and technical information will be posted as research continues and will explore other techniques— such as the use of marbled papers, stencils, gold leaf, drawing, and painting—that were employed by artists and calligraphers of the time.

Endnotes

- Muraqqa' is a Persian word meaning patched or patchwork and relates to a description of the garments worn by Dervish members of the Sufi religion. Dervish took vows of material poverty and were known to wear garments that had been patched and mended over time and passed on to other members. Muraqqa' are similarly patched together, were passed down within families, and often include paintings and calligraphy spanning many years, decades, and even centuries (Thackston 2001 and Roxburgh 2005).

- The Read Album leaves were discussed in a study published by Barbara Schmitz in 1997. Schmitz has linked many connecting leaves within the collection and has identified leaves that may have been an album’s frontispiece (decorated opening at the beginning of a book).

- Mixtures of metallic pigments have been observed in Persian paintings (Puritan & Watters 1991), and a recent study of elemental and compound analysis of Islamic manuscripts at the Harvard Art Museums has found mixtures of pure and silver-rich gold paint (Knipe et al. 2019).

- Roxburgh 2005.

- Benham n.d. and Rogers 2007.

References List

Benham, Alanna M. “Persian, Mughal, and Indian Miniature Paintings,” Brown University Library Center for Digital Scholarship. Accessed March 30, 2020.

Knipe, P., Eremin, K., Walton, M, et al. 2018. “Materials and Techniques of Islamic Manuscripts.” Heritage Science No. 6, Vol 55 (2018).

Puritan, Nancy and Watters, Mark. 1991. “A Study of the Materials Used by Medieval Persian Painters.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, Vol. 30, No. 2: 125-144.

Rogers, J.M. 2007. Mughal Miniatures. Northampton, Massachusetts: Interlink Books.

Roxburgh, David J. 2005. The Persian Album 1400–1600: From Dispersal to Collection. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Schmitz, Barbara. 1997. Islamic and Indian Manuscripts and Paintings at the Pierpont Morgan Library, contributions by Pratapaditya Pal, Wheeler M. Thackston, and William M. Voelkle, New York: Pierpoint Morgan Library.

Thackston, Wheeler M. 2001. Album Prefaces and Other Documents on the History of Calligraphers and Painters. Leiden,The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

Images

Graham S. Haber, figures 1, 2, 7; Bonnie Hearn, figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11.

Yvonne (Bonnie) Hearn is the 2018–2020 Sherman Fairchild Post Graduate Fellow in Paper Conservation. She was the 2016–2018 Ian Potter Foundation Fellow in Paper Conservation at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. Bonnie has worked in conservation at the Grimwade Centre for Cultural Material and Conservation, Commercial Services, the University of Melbourne and State Library Victoria. She holds a BA in Fine Arts (specializing in printmaking) from the Victorian College of the Arts (2011) and an MA in Cultural Materials Conservation (specializing in paper conservation) from the University of Melbourne (2013). During her current fellowship, Bonnie has undertaken research on and conservation treatment of many of the Morgan’s collections including the Read Album leaves.