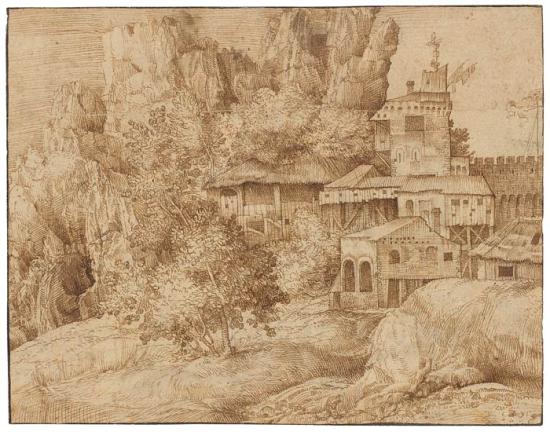

Buildings in a Rocky Landscape

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Engraver and draftsman Giulio Campagnola arrived in Venice in 1507, where he worked in the entourage of Giorgione. Campagnola and his adopted son, Domenico, introduced a new specialty into Venetian art—the pure, narrative-free landscape. Their large, panoramic landscapes created with flowing rhythmic strokes informed succeeding generations, including Pieter Bruegel, Goltzius, and Rubens, and were much sought after by cultivated collectors.

The dense cross-hatching and extreme delicacy with which the artist rendered the picturesque cluster of buildings suggest the influence of both Albrecht Dürer and Giorgione.

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.