The First Simultaneous Book

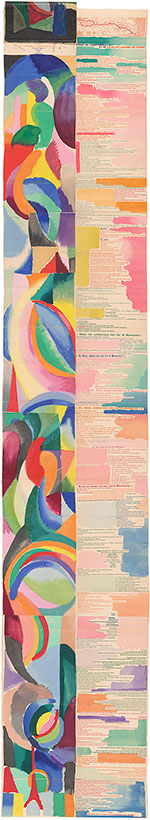

The visual presentation of Blaise Cendrars’s La prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France was initially conceived by the Ukrainian-born artist Sonia Delaunay-Terk (1885–1979). When Cendrars met her and her husband, the painter Robert Delaunay, in Paris, the couple was exploring Simultanism in chiefly abstract paintings. Their idea, based on color theory, held that a viewer’s simultaneous perception of contrasting hues generates rhythm, emotion, movement, and depth.

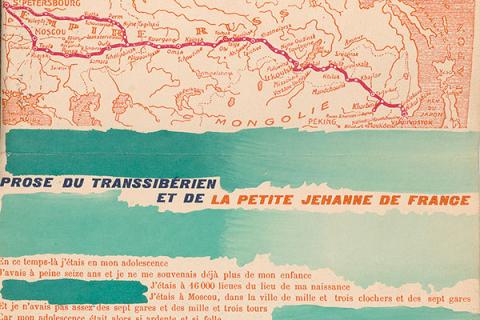

Inspired by Cendrars’s recitations of his poetry, Delaunay-Terk proposed that they collaborate on a “simultaneous book,” with his text set in contrasting colors parallel to her designs. Cendrars formatted the poem using thirty typefaces, which were letterpress printed on the right side of four large sheets. Delaunay-Terk’s painted maquette was converted into dozens of stencils (a technique called pochoir), through which printshop workers hand applied gouache with a brush, one color at a time. The four sheets were then pasted together and accordion-folded like a travel map or a string of picture postcards. Cendrars and Delaunay-Terk planned to produce 150 copies, so that, if placed vertically end to end, the edition would reach the top of the Eiffel Tower. Little more than half that number were realized, and far fewer survive.

The Morgan's copy was inscribed by Cendrars to the American painter Morgan Russell (1886–1953). It was acquired by art historian Gail Levin from Russell’s widow, Suzanne Raingo Russell. In 2021, Dr. Levin donated it to the Morgan Library & Museum.

Poetry in Motion

Across 446 lines, Cendrars's freewheeling travel poem fuses reality, memory, and imagination in a breathless flow of spontaneous impressions. Narrated by a man named Blaise, the poem takes place on a train trip from Russia to China, though it concludes in Paris. In free verse, with virtually no punctuation, Cendrars’s lines are rife with imagery of war and revolution, interwoven with the minutiae of daily life and casual references to the New York Public Library and to his friends Marc Chagall and Guillaume Apollinaire. Occasionally, the narrator’s litany is interrupted by the voice of his travel companion, Jeanne: “Say, Blaise, are we really a long way from Montmartre?”

Cendrars’s time spent in Russia and the narrator’s name led readers to assume that the work was autobiographical. But the poem’s journey undoubtedly occurred in Cendrars’s imagination: among his belongings was a poster for a panorama restaurant at the 1900 World Exposition in Paris, where guests dined in stationary railroad cars, as painted scenes of the 6,000-mile journey scrolled by.

Read the entire poem in an English translation by Ron Padgett.

Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412