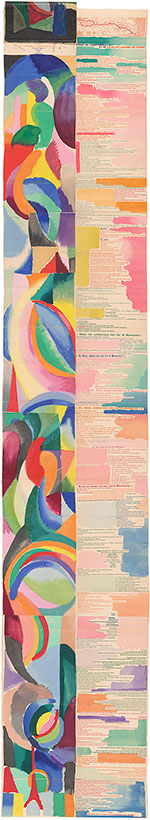

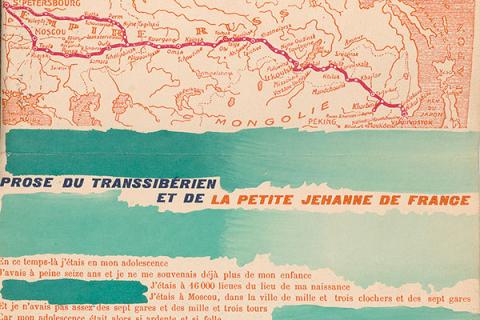

La prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France

The First Simultaneous Book

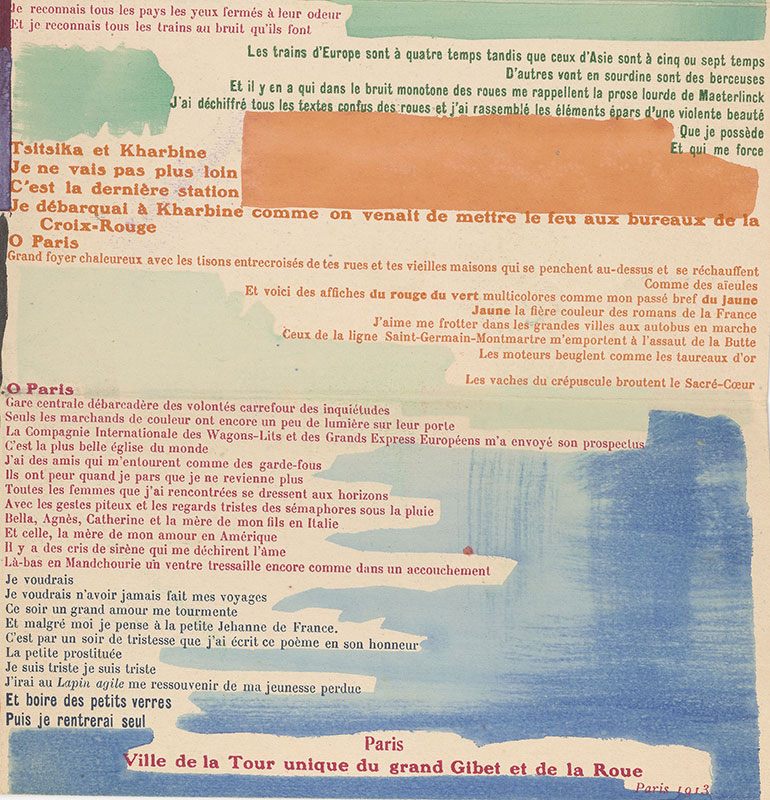

The visual presentation of Blaise Cendrars’s La prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France was initially conceived by the Ukrainian-born artist Sonia Delaunay-Terk (1885–1979). When Cendrars met her and her husband, the painter Robert Delaunay, in Paris, the couple was exploring Simultanism in chiefly abstract paintings. Their idea, based on color theory, held that a viewer’s simultaneous perception of contrasting hues generates rhythm, emotion, movement, and depth.

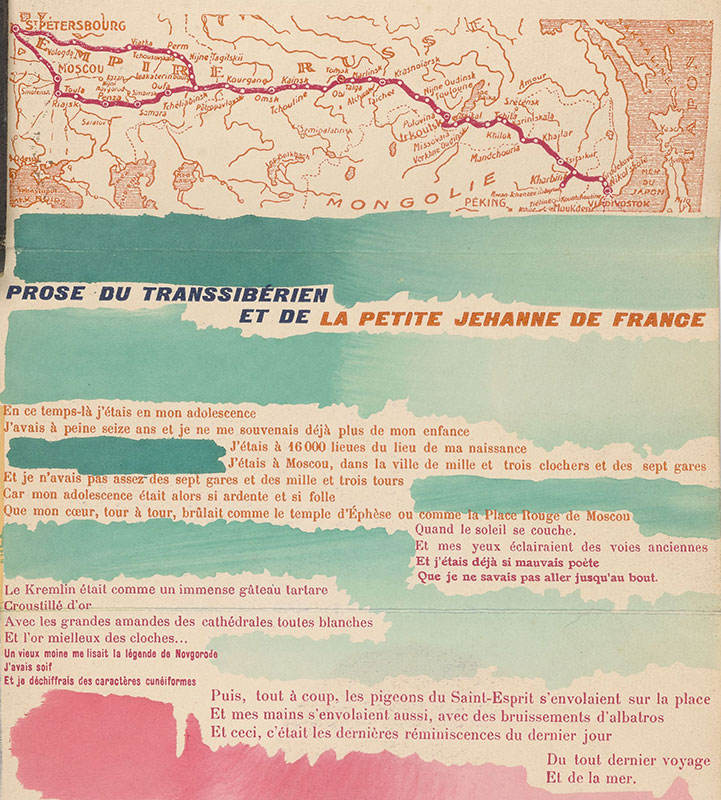

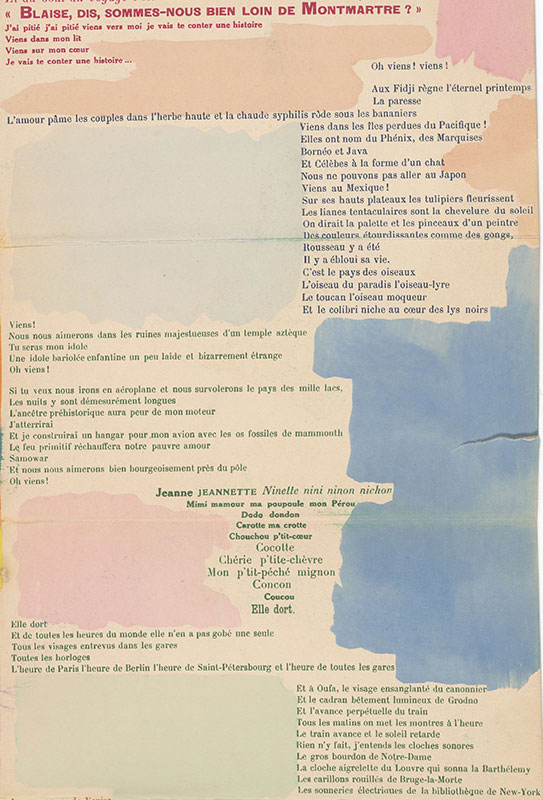

Inspired by Cendrars’s recitations of his poetry, Delaunay-Terk proposed that they collaborate on a “simultaneous book,” with his text set in contrasting colors parallel to her designs. Cendrars formatted the poem using thirty typefaces, which were letterpress printed on the right side of four large sheets. Delaunay-Terk’s painted maquette was converted into dozens of stencils (a technique called pochoir), through which printshop workers hand applied gouache with a brush, one color at a time. The four sheets were then pasted together and accordion-folded like a travel map or a string of picture postcards. Cendrars and Delaunay-Terk planned to produce 150 copies, so that, if placed vertically end to end, the edition would reach the top of the Eiffel Tower. Little more than half that number were realized, and far fewer survive.

The Morgan's copy was inscribed by Cendrars to the American painter Morgan Russell (1886–1953). It was acquired by art historian Gail Levin from Russell’s widow, Suzanne Raingo Russell. In 2021, Dr. Levin donated it to the Morgan Library & Museum.

Poetry in Motion

Across 446 lines, Cendrars's freewheeling travel poem fuses reality, memory, and imagination in a breathless flow of spontaneous impressions. Narrated by a man named Blaise, the poem takes place on a train trip from Russia to China, though it concludes in Paris. In free verse, with virtually no punctuation, Cendrars’s lines are rife with imagery of war and revolution, interwoven with the minutiae of daily life and casual references to the New York Public Library and to his friends Marc Chagall and Guillaume Apollinaire. Occasionally, the narrator’s litany is interrupted by the voice of his travel companion, Jeanne: “Say, Blaise, are we really a long way from Montmartre?”

Cendrars’s time spent in Russia and the narrator’s name led readers to assume that the work was autobiographical. But the poem’s journey undoubtedly occurred in Cendrars’s imagination: among his belongings was a poster for a panorama restaurant at the 1900 World Exposition in Paris, where guests dined in stationary railroad cars, as painted scenes of the 6,000-mile journey scrolled by.

Read the entire poem in an English translation by Ron Padgett.

Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412

Translation p. 1

“The Prose of the Trans-Siberian and of Little Jeanne of France” by Blaise Cendrars

Translated by Ron Padgett

From Blaise Cendrars: Complete Poems (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992)

Dedicated to the musicians

Back then I was still young

I was barely sixteen but my childhood memories were gone

I was 48,000 miles away from where I was born

I was in Moscow, city of a thousand and three bell towers and seven

train stations

And the thousand and three towers and seven stations weren’t enough

for me

Because I was such a hot and crazy teenager

That my heart was burning like the Temple of Ephesus or like Red

Square in Moscow

At sunset

And my eyes were shining down those old roads

And I was already such a bad poet

That I didn't know how to take it all the way.

The Kremlin was like an immense Tartar cake

Iced with gold

With big blanched-almond cathedrals

And the honey gold of the bells . . .

An old monk was reading me the legend of Novgorod

I was thirsty

And I was deciphering cuneiform characters

Then all at once the pigeons of the Holy Ghost flew up over the square

And my hands flew up too, sounding like an albatross taking off

And, well, that’s the last I remember of the last day

Of the very last trip

And of the sea.

Detail of Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412

Translation p. 2

Still, I was a really bad poet.

I didn't know how to take it all the way.

I was hungry

And all those days and all those women in all those cafés and all those

glasses

I wanted to drink them down and break them

And all those windows and all those streets

And all those houses and all those lives

And all those carriage wheels raising swirls from the broken pavement

I would have liked to have rammed them into a roaring furnace

And I would have liked to have ground up all their bones

And ripped out all those tongues

And liquefied all those big bodies naked and strange under clothes that

drive me mad . . .

I foresaw the coming of the big red Christ of the Russian Revolution . . .

And the sun was an ugly sore

Splitting apart like a red-hot coal.

Back then I was still quite young

I was barely sixteen but I’d already forgotten about where I was born

I was in Moscow wanting to wolf down flames

And there weren’t enough of those towers and stations sparkling in

my eyes

In Siberia the artillery rumbled—it was war

Hunger cold plague cholera

And the muddy waters of the Amur carrying along millions of corpses

In every station I watched the last trains leave

That’s all: they weren't selling any more tickets

And the soldiers would far rather have stayed . . .

An old monk was singing me the legend of Novgorod.

Me, the bad poet who wanted to go nowhere, I could go anywhere

And of course the businessmen still had enough money

To go out and seek their fortunes.

Their train left every Friday morning.

It sounded like a lot of people were dying.

One guy took along a hundred cases of alarm clocks and cuckoo clocks

from the Black Forest

Another took hatboxes, stovepipes, and an assortment of Sheffield

corkscrews

Another, coffins from Malmo filled with canned goods and sardines

in oil

And there were a lot of women

Women with vacant thighs for hire

Who could also serve

Coffins

They were all licensed

It sounded like a lot of people were dying out there

The women traveled at a reduced fare

And they all had bank accounts.

Now, one Friday morning it was my turn to go

It was in December

And I left too, with a traveling jewel merchant on his way to Harbin

We had two compartments on the express and 34 boxes of jewelry from

Pforzheim

German junk “Made in Germany”

He had bought me some new clothes and I had lost a button getting on

the train

—I remember, I remember, I’ve often thought about it since—

I slept on the jewels and felt great playing with the nickel-plated

Browning he had given me

I was very happy and careless

Detail of Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412

Translation p. 3

It was like Cops and Robbers

We had stolen the treasure of Golconda

And we were taking it on the Trans-Siberian to hide it on the other side

of the world

I had to guard it from the thieves in the Urals who had attacked the

circus caravan in Jules Verne

From the Khunkhuz, the Boxers of China

And the angry little Mongols of the Great Lama

Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves

And the followers of the terrible Old Man of the Mountain

And worst of all, the most modern

The cat burglars

And the specialists of the international express.

And still, and still

I was as sad as a little boy

The rhythms of the train

What American psychiatrists call “railroad nerves”

The noise of doors voices axles screeching along frozen rails

The golden thread of my future

My Browning the piano the swearing of the card players in the next

compartment

The terrific presence of Jeanne

The man in blue glasses nervously pacing up and down the corridor

and glancing in at me

Swishing of women

And the whistle blowing

And the eternal sound of the wheels wildly rolling along ruts in the sky

The windows frosted over

No nature!

And out there the Siberian plains the low sky the big shadows of the

Taciturns rising and falling

I’m asleep in a tartan

Plaid

Like my life

With my life keeping me no warmer than this Scotch

Shawl

And all of Europe seen through the wind-cutter of an express at top

speed

No richer than my life

My poor life

This shawl

Frayed on strongboxes full of gold

I roll along with

Dream

And smoke

And the only flame in the universe

Is a poor thought . . .

Detail of Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412

Translation p. 4

Tears rise from the bottom of my heart

If I think, O Love, of my mistress;

She is but a child, whom I found, so pale

And pure, in the back of a bordel.

She is but a fair child who laughs,

Is sad, doesn’t smile, and never cries;

But the poet’s flower, the silver lily, trembles

When she lets you see it in the depths of her eyes.

She is sweet, says nothing you can hear,

With a long, slow trembling when you draw near;

But when I come to her, from here, from there,

She takes a step and shuts her eyes—and takes a step.

For she is my love and other women

Are but big bodies of flame sheathed in gold,

My poor friend is so alone

She is stark naked, has no body—she’s too poor.

She is but an innocent flower, all thin and delicate,

The poet’s flower, a pathetic silver lily,

So cold, so alone, and so wilted now

That tears rise if I think of her heart.

And this night is like a hundred thousand others when a train slips

through the night

—Comets fall—

And a man and a woman, no matter how young, enjoy making love.

The sky is like the torn tent of a rundown circus in a little fishing village

In Flanders

The sun like a smoking lamp

And way up on the trapeze a woman does a crescent moon

The clarinet the trumpet a shrill flute a beat-up drum

And here is my cradle

My cradle

It was always near the piano when my mother, like Madame Bovary,

played Beethoven’s sonatas

I spent my childhood in the hanging gardens of Babylon

Playing hooky, following the trains as they pulled out of the stations

Now I’ve made the trains follow me

Basel – Timbuktu

I’ve played the horses at tracks like Auteuil and Longchamps

Paris – New York

Now the trains run alongside me

Madrid – Stockholm

Lost it all at the gay pari-mutuel

Patagonia is what’s left, Patagonia, which befits my immense sadness,

Patagonia and a trip to the South Seas

Detail of Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412

Translation p. 5

I’m on the road

I’ve always been on the road

I’m on the road with little Jeanne of France

The train does a somersault and lands on all fours

The train lands on its wheels

The train always lands on all its wheels

“Blaise, say, are we really a long way from Montmartre?”

A long way, Jeanne, you’ve been rolling along for seven days

You’re a long way from Montmartre, from the Butte that brought you

up, from the Sacré-Cœur you snuggled up to

Paris has disappeared with its enormous blaze

Everything gone except cinders flying back

The rain falling

The peat bogs swelling

Siberia turning

Heavy sheets of snow piling up

And the bell of madness that jingles like a final desire in the bluish air

The train throbs at the heart of the leaden horizon

And your desolation snickers . . .

“Say, Blaise, are we really a long way from Montmartre?”

Troubles

Forget your troubles

All the cracked and leaning stations along the way

The telegraph lines they hang from

The grimacing poles that reach out to strangle them

The world stretches out elongates and snaps back like an accordion in

the hands of a raging sadist

Wild locomotives fly through rips in the sky

And in the holes

The dizzying wheels the mouths the voices

And the dogs of misery that bark at our heels

The demons are unleashed

Scrap iron

Everything clanks

Slightly off

The clickety-clack of the wheels

Lurches

Jerks

We are a storm in the skull of a deaf man . . .

Detail of Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412

Translation p. 6

“Say, Blaise, are we really a long way from Montmartre?”

Of course we are, stop bothering me, you know we are, a long way

An overheated madness bellows in the locomotive

Plague and cholera rise like burning embers around us

We disappear right into a tunnel of war

Hunger, that whore, clutches the clouds scattered across the sky and

craps on the battlefield piles of stinking corpses

Do what it does, do your job . . .

“Say, Blaise, are we really a long way from Montmartre?”

Yes, we are, we are

All the scapegoats have swollen up and collapsed in this desert

Listen to the cowbells of this mangy troop

Tomsk Chelyabinsk Kansk Ob’ Tayshet Verkne-Udinsk Kurgan Samara

Penza-Tulun

Death in Manchuria

Is where we get off is our last stop

This trip is terrible

Yesterday morning

Ivan Ulitch’s hair turned white

And Kolia Nikolai Ivanovitch has been biting his fingers for two

weeks . . .

Do what Death and Famine do, do your job

It costs one hundred sous—in Trans-Siberian that’s one hundred rubles

Fire up the seats and blush under the table

The devil is at the keyboard

His knotty fingers thrill all the women

Instinct

OK gals

Do your job

Until we get to Harbin . . .

“Say, Blaise, are we really a long way from Montmartre?”

No, hey . . . Stop bothering me . . . Leave me alone

Your pelvis sticks out

Your belly’s sour and you have the clap

The only thing Paris laid in your lap

And there’s a little soul . . . because you’re unhappy

I feel sorry for you come here to my heart

The wheels are windmills in the land of Cockaigne

And the windmills are crutches a beggar whirls over his head

We are the amputees of space

We move on our four wounds

Our wings have been clipped

The wings of our seven sins

And the trains are all the devil’s toys

Chicken coop

The modern world

Speed is of no use

The modern world

The distances are too far away

And at the end of a trip it’s horrible to be a man with a woman . . .

Detail of Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412

Translation p. 7

“Blaise, say, are we really a long way from Montmartre?”

I feel so sorry for you come here I’m going to tell you a story

Come get in my bed

Put your head on my shoulder

I’m going to tell you a story . . .

Oh come on!

It’s always spring in the Fijis

You lay around

The lovers swoon in the high grass and hot syphilis drifts among the

banana trees

Come to the lost islands of the Pacific!

Names like Phoenix, the Marquesas

Borneo and Java

And Celebes shaped like a cat

We can’t go to Japan

Come to Mexico!

Tulip trees flourish on the high plateaus

Clinging vines hang down like hair from the sun

It’s as if the brushes and palette of a painter

Had used colors stunning as gongs—

Rousseau was there

It dazzled him forever

It’s a great bird country

The bird of paradise the lyre bird

The toucan the mockingbird

And the hummingbird nests in the heart of the black lily

Come!

We’ll love each other in the majestic ruins of an Aztec temple

You’ll be my idol

Splashed with color childish slightly ugly and really weird

Oh come!

If you want we’ll take a plane and fly over the land of the thousand lakes

The nights there are outrageously long

The sound of the engine will scare our prehistoric ancestors

I’ll land

And build a hangar out of mammoth fossils

The primitive fire will rekindle our poor love

Samovar

And we’ll settle down like ordinary folks near the pole

Oh come!

Jeanne Jeannette my pet my pot my poot

My me mama poopoo Peru

Peepee cuckoo

Ding ding my dong

Sweet pea sweet flea sweet bumblebee

Chickadee beddy-bye

Little dove my love

Little cookie-nookie

Asleep.

She’s asleep

And she hasn’t taken in a thing the whole way

All those faces glimpsed in the stations

All the clocks

Paris time Berlin time Saint Petersburg time all those stations’ times

And at Ufa the bloody face of the cannoneer

And the absurdly luminous dial at Grodno

And the train moving forward endlessly

Every morning you set your watch ahead

The train moves forward and the sun loses time

It’s no use! I hear the bells

The big bell at Notre-Dame

The sharp bell at the Louvre that rang on Saint Bartholomew’s Day

The rusty carillons of Bruges-the-Dead

The electric bells of the New York Public Library

Detail of Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412

Translation p. 8

The campaniles of Venice

And the bells of Moscow ringing, the clock at Red Gate that kept time

for me when I was working in an office

And my memories

The train thunders into the roundhouse

The train rolls along

A gramophone blurts out a tinny Bohemian march

And the world, like the hands of the clock in the Jewish section of

Prague, turns wildly backwards.

Cast caution to the winds

Now the storm is raging

And the trains storm over tangled tracks

Infernal toys

There are trains that never meet

Others just get lost

The stationmasters play chess

Backgammon

Shoot pool

Carom shots

Parabolas

The railway system is a new geometry

Syracuse

Archimedes

And the soldiers who butchered him

And the galleys

And the warships

And the astounding engines he invented

And all that killing

Ancient history

Modern history

Vortex

Shipwreck

Even that of the Titanic I read about in the paper

So many associations images I can’t get into my poem

Because I’m still such a really bad poet

Because the universe rushes over me

And I didn’t bother to insure myself against train wreck

Because I don’t know how to take it all the way

And I’m scared.

I’m scared

I don’t know how to take it all the way.

Like my friend Chagall I could do a series of irrational paintings

But I didn’t take notes

“Forgive my ignorance

Pardon my forgetting how to play the ancient game of Verse”

As Guillaume Apollinaire says

If you want to know anything about the war read Kuropotkin’s Memoirs

Or the Japanese newspapers with their ghastly illustrations

But why compile a bibliography

I give up

Bounce back into my leaping memory . . .

Detail of Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412

Translation p. 9

At Irkutsk the trip suddenly slows down

Really drags

We were the first train to wind around Lake Baikal

The locomotive was decked out with flags and lanterns

And we had left the station to the sad sound of “God Save the Czar.”

If I were a painter I would splash lots of red and yellow over the end of

this trip

Because I think we were all slightly crazy

And that an overwhelming delirium brought blood to the exhausted

faces of my traveling companions

As we came closer to Mongolia

Which roared like a forest fire.

The train had slowed down

And in the perpetual screeching of wheels I heard

The insane sobbing and screaming

Of an eternal liturgy

I saw

I saw the silent trains the black trains returning from the Far East and

going by like phantoms

And my eyes, like tail lights, are still trailing along behind those trains

At Talga 100,000 wounded were dying with no help coming

I went to the hospitals in Krasnoyarsk

And at Khilok we met a long convoy of soldiers gone insane

I saw in quarantine gaping sores and wounds with blood gushing out

And the amputated limbs danced around or flew up in the raw air

Fire was in their faces and in their hearts

Idiot fingers drumming on all the windowpanes

And under the pressure of fear an expression would burst like an abscess

In all the stations they had set fire to all the cars

And I saw

I saw trains with 60 locomotives streaking away chased by hot horizons

and desperate crows

Disappearing

In the direction of Port Arthur.

At Chita we had a few days’ rest

A five-day stop while they cleared the tracks

We stayed with Mr. Iankelevitch who wanted me to marry his only

daughter

Then it was time to go.

Now I was the one playing the piano and I had a toothache

And when I want I can see it all again those quiet rooms the store and

the eyes of the daughter who slept with me every night

Mussorgsky

And the lieder of Hugo Wolf

And the sands of the Gobi Desert

And at Khailar a caravan of white camels

I’d swear I was drunk for over 300 miles

But I was playing the piano—it’s all I saw

You should close your eyes on a trip

And sleep

I was dying to sleep

Detail of Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412

Translation p. 10

With my eyes closed I can smell what country I’m in

And I can hear what kind of train is going by

European trains are in 4/4 while the Asian ones are 5/4 or 7/4

Others go humming along are like lullabies

And there are some whose wheels’ monotone reminds me of the heavy

prose of Maeterlinck

I deciphered all the garbled texts of the wheels and united the scattered

elements of a violent beauty

Which I possess

And which drives me

Tsitsihar and Harbin

That’s as far as I go

The last station

I stepped off the train at Harbin a minute after they had set fire to the

Red Cross office.

O Paris

Great warm hearth with the intersecting embers of your streets and your

old houses leaning over them for warmth

Like grandmothers

And here are posters in red in green all colors like my past in a word

yellow

Yellow the proud color of the novels of France

In big cities I like to rub elbows with the buses as they go by

Those of the Saint-Germain–Montmartre line that carry me to the

assault of the Butte

The motors bellow like golden bulls

The cows of dusk graze on Sacré-Cœur

O Paris

Main station where desires arrive at the crossroads of restlessness

Now only the paint store has a little light on its door

The International Pullman and Great European Express Company has

sent me its brochure

It’s the most beautiful church in the world

I have friends who surround me like guardrails

They’re afraid that when I leave I’ll never come back

All the women I’ve ever known appear around me on the horizon

Holding out their arms and looking like sad lighthouses in the rain

Bella, Agnès, Catherine, and the mother of my son in Italy

And she who is the mother of my love in America

Sometimes the cry of a whistle tears me apart

Over in Manchuria a belly is still heaving, as if giving birth

I wish

I wish I’d never started traveling

Tonight a great love is driving me out of my mind

And I can’t help thinking about little Jeanne of France.

It’s through a sad night that I’ve written this poem in her honor

Jeanne

The little prostitute

I’m sad so sad

I’m going to the Lapin Agile to remember my lost youth again

Have a few drinks

And come back home alone

Paris

City of the incomparable Tower the great Gibbet and the Wheel

Paris, 1913

—Translated by Ron Padgett

Detail of Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961), La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Illustrations by Sonia Delaunay-Terk (Paris: Éditions des hommes nouveaux, 1913). Gift of Dr. Gail Levin, 2021; PML 198726 © Blaise Cendrars/Succession Cendrars. © Pracusa 20230412