Belle da Costa Greene: A Portrait Gallery

As part of its ongoing project to illuminate the career of librarian, curator, scholar, and cultural executive Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950), the Morgan presents this digital gallery of all known photographs and portraits depicting her. Appropriately, both the earliest surviving life portrait (a 1900 photograph of her summer school library course at Amherst College) and the last (a photograph taken in the late 1940s after her retirement) depict Greene in a library-related setting, surrounded by budding librarians as well as the books and manuscripts to which she devoted her four-decade career.

There is no known film footage of Greene and there are no known audio recordings of her voice.

Amherst College Summer School

Belle Greene attended the Northfield Seminary for Young Ladies in Northfield, MA from 1896–1898 and did not leave with a degree, which was common for many of the school’s students at this time. In 1900 she attended the Summer School of Library Economy at Amherst College, about twenty-five miles south of Northfield. There she also learned the upright cursive handwriting she later used in her research notes and catalogue cards at the Morgan. This group photograph contains the earliest known image of Belle Greene, taken when she was twenty years old. She can be seen in the back row, against the ivy, with a wry smile and knowing expression. Like the other sitters, she signed the back of the photograph, where she recorded her name and hometown as “Belle Marion Greene, New York City.”

Amherst College Summer School, Fletcher Course in Library Economy, Class of 1900, 1900

Gelatin silver print

9 × 11 in. (22.9 × 27.9 cm)

Amherst College Archives

Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

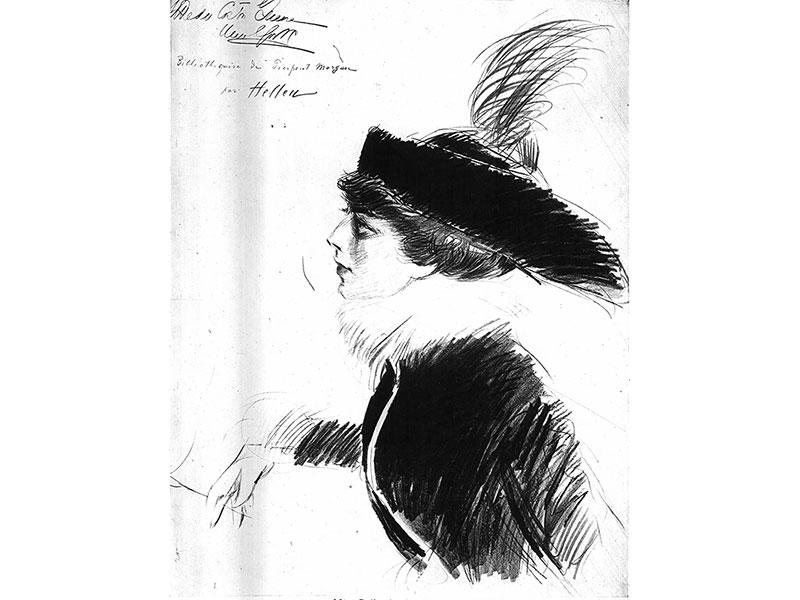

Otto J. Schneider

This etching was made by the American artist Otto J. Schneider, who created portraits of stylish American women and historical figures such as Abraham Lincoln and Henry David Thoreau. In a letter dated 29 June 1909, Greene told Bernard Berenson that Schneider had made the portrait from memory after visiting her office (the elegant North Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library) and seeing her deep in bibliographical research with "half the Library" spread out on her desk.

Schneider worked as a newspaper illustrator, and took evening classes at the Art Institute of Chicago before moving to NY in 1903. He mainly created portraits of women, and worked almost exclusively in dry-point etching, not working with acid. An article in Cosmopolitan says that he was influenced by the French artist Paul Helleu’s depictions of women. He did make some portraits of men, and some in color. He made his own prints.

BG to BB, 6/29/09 (29): “I am sending you by this post an etching which Otto Schneider made of me at my desk – exacting the promise beforehand, that you will destroy it after a glance – It has no merit as a portrait of me – and really none at all except that it was done from memory – He came into the library one day when I was busily engaged hunting up particulars of a certain book & half the Library was on my desk – and he went away & made this etching & sent it to me the next-morning – for that reason I tolerate it but I really hate to think I am quite as vacant minded as it would lead one to suppose – [double underlined: also] I think it will make a delicious companion piece to my real (?) self as shown by your friend’s drawing”

Otto J. Schneider (1875–1946)

Belle da Costa Greene at Her Desk in the North Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1909

Drypoint etching; 12 3/16 × 16 5/16 in. (30.9 × 41.3 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; ARC 3271

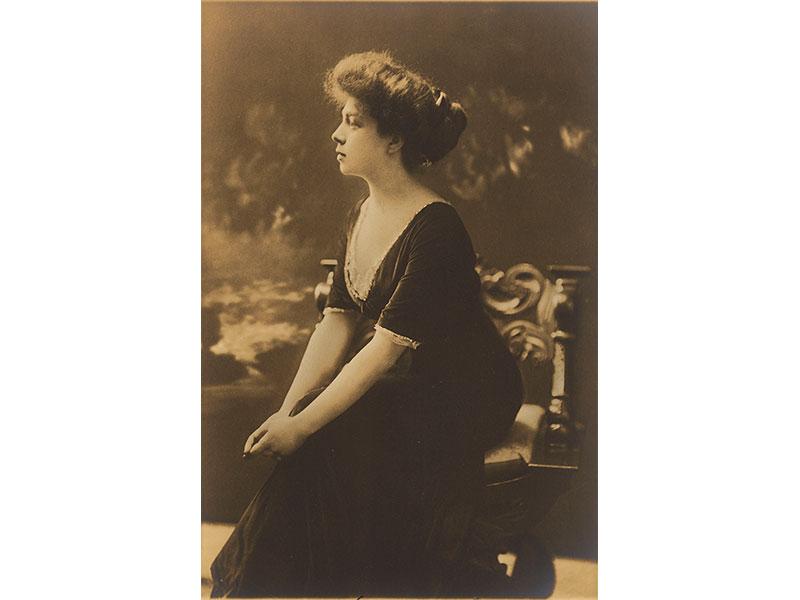

Ernest Walter Histed

This is the earliest known solo photographic portrait of Greene, taken by the British-born photographer E. W. Histed, presumably at his Fifth Avenue studio about a half-mile north of J. Pierpont Morgan's Library. Before Greene sat for him in 1910, Histed had photographed countless luminaries from Queen Victoria to Mark Twain. Both his 1898 portrait of the actor Lily Hanbury and this 1910 photograph of Greene depict the subjects in elegant profile.

BG to BB, 4/19/10 (65; possible reference to this photograph): “I will have my photograph taken when I return from Boston on the 15th of May – I am too worn out now – You would not recognize me & I weigh fully fifteen pounds less than when you saw me last – “Aint – Grand?””

BG to BB, 6/9/10 (68; possible reference to this photograph): “I am sending you a “real” photograph such as you demand today – It may look rather sad for the simple reason that I was thinking of you all the time it was being taken [underlined multiple times: (honestly)] & that always makes me sad – Even if we meet soon & for a long time I shall never get enough of you to make up for all this hideously long time”

Ernest Walter Histed (1862–1947)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1910

Gelatin silver print; 23 × 18 in. (58.42 × 45.72 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; ARC 2702

Laura Coombs Hills

.jpg)

The only known portrait of Greene by a woman artist, this small-scale watercolor on ivory was created in 1910 by the miniaturist Laura Coombs Hills. Greene traveled to Boston more than once to sit for Hills, and she was apparently pleased with the result. Hills asked Greene if she could borrow the miniature for an exhibition in 1912, but Greene refused to lend it. Greene apparently liked this portrait and her comments on her "Egyptian" appearance offer fascinating insight into the ways she exoticized herself from time to time in letters to Bernard Berenson.

BG to BB, 2/24/10 (55): “I am having my portrait painted in an old Spanish shawl that the Big Chief gave me – It is very tedious & tiresome work and I shall be glad when it is finished – but alas! I promised to sit for Laura Hills in Boston in April. She wants to make a miniature of me, seated on a leopard’s skin! Don’t you think that is a horrible idea? She insists that it will be the best thing she has done”

BG to BB, 3/11/10 (58): “I shall probably remain there until April 15th on which day I go to Boston to give Laura Hills a chance to finish a miniature of me – and shall probably be back here on May 1st”

BG to BB, 6/7/10 (67): “I am sending you by mail today a photograph of Laura Hills miniature of me – It is a horrid photo & it really is not fair to her to send it to you – but I felt that something that was me must go to you at once The whole value of the portrait really lies in the coloring which is quite wonderful – the veil which I have around me is a most wonderful glowing saffron with high lights of sunset colors in it & the background is a dull gold – It is not the Belle that you know but you will know her some day & you, I think will like her – It is the Belle of one of my former incarnations “Egyptienne” – If you don’t like it just tear it up”

Laura Coombs Hills (1859–1952)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1910

Watercolor on ivory; 5 3/4 × 4 1/4 in. (14.6 × 10.8 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, gift of the Estate of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950; AZ164

Photographer unknown

Greene inscribed this photograph—the only known print of this image—to "Rosie," her nickname for the Philadelphia bookseller A.S.W. Rosenbach (1876–1952), her friend, professional colleague, and fellow expert on rare printed books. The undated photograph is likely from the 1910s; it is known to be no later than 1921 because a reproduction appeared in a newspaper article that year. In “Mighty Women Book Hunters,” a chapter in his 1936 memoir A Book Hunter’s Holiday, Rosenbach expressed his esteem for Greene and noted her professional stature: “This reference to the Morgan collection must inevitably bring up the name of its distinguished director, Miss Belle da Costa Greene, who has reached a height in the world of books that no other woman has ever attained. Miss Greene, besides possessing a genuine love of books, has a knowledge of customs and manners in the medieval period excelled by few scholars.”

Photographer unknown

Belle da Costa Greene, ca. 1911 (1921 or earlier)

9 1/3 x 6 3/4 in.

The Rosenbach, Philadelphia. 2006.2218.

Inscribed to A.S.W. Rosenbach (To Rosie / BG)

Alexander Popini

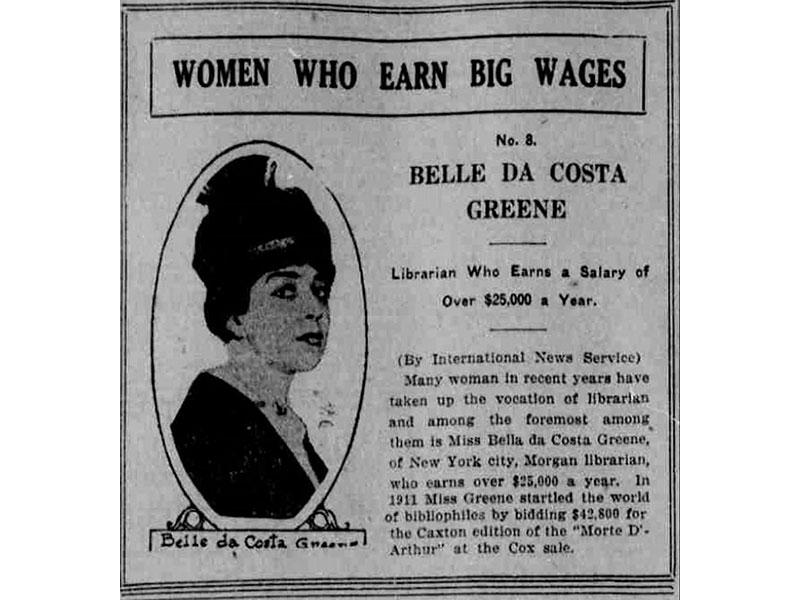

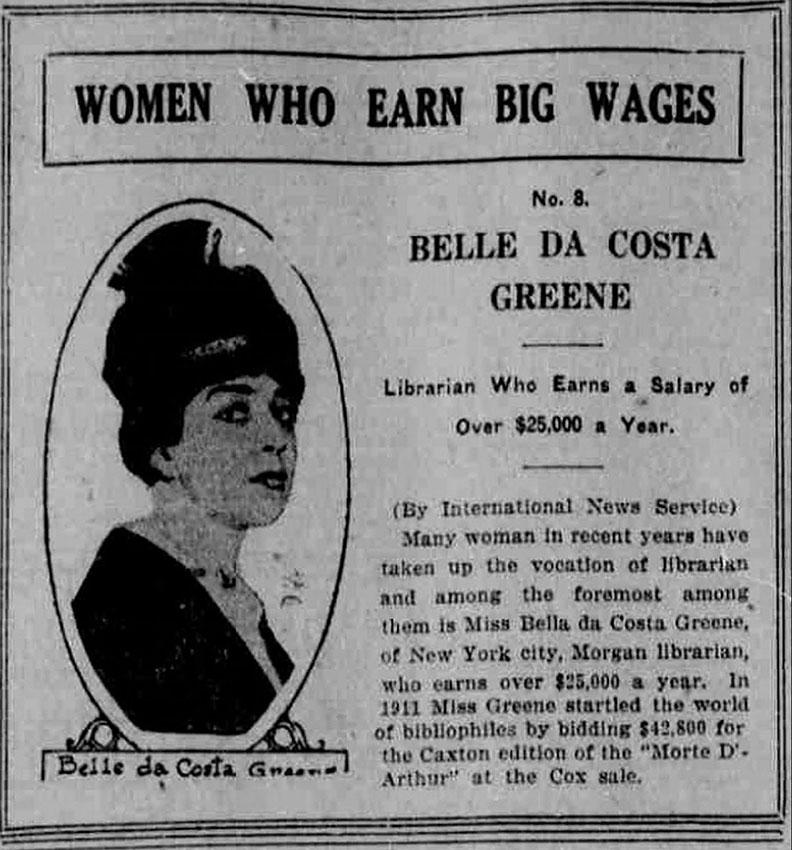

One of many newspaper articles to discuss the sale of Robert Hoe's library in the spring of 1911, this is the only one that visually depicts Belle Greene on the auction floor, where she was one of two women in attendance. Greene herself saved several clippings from media coverage of this sale, but not this particular article, which she seemed to dislike intensely.

BG to BB, 5/21/11 (154): “We arrived about brutal and I was “all in” so went immediately to bed and was awakened by mother bending over & holding up a horrible vision of myself in the Sunday World – full page & brightly coloured Well I had a dozen different fits of anger and despair. You can’t do a thing with these damned newspapers – and although it said in the accompanying article that I was very quiet – & self-contained yet this picture was of half actress and half college girl – It really is too mean of them. If I behave in a dignified way when attending to my business why can’t they treat me in the same way in their newspaper or better still why can’t they leave me out? I was so cross that it has given me a violent headache & so I am spending the morning in bed”

Alexander Popini (1878–1962)

"Fifty Thousand Dollars for that Book!" The World Magazine, May 21, 1911

Illustration by Alexander Popini based on photograph by an unknown photographer

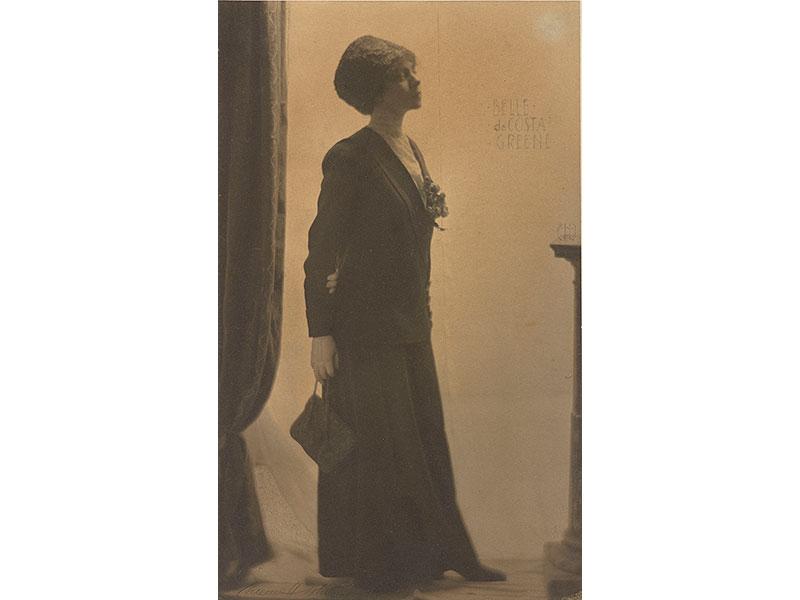

Clarence H. White

Arguably the most famous photographs of Belle da Costa Greene were taken by the photographer Clarence H. White in 1911. There are nine known images of Greene by White, with prints preserved at the Morgan, I Tatti, and Princeton University Art Museum. Those at I Tatti were given to Bernard Berenson by Greene, who appears to make several references to them in her letters to Bernard. White was part of the circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291 (named for its Fifth Avenue address). Greene knew and corresponded with Stieglitz, attended exhibitions at 291 (acquiring a Matisse drawing and Steichen photographic print there), and was caricatured by the Mexican-American artist Marius de Zayas, who also caricatured Clarence White. According to art historian Anne McCauley, Belle Greene wore in these photographs "a new type of close-fitting hat that conveniently hid her revealingly African American hair" (116). The few quotes in her letters to Berenson that seem to reference the White series note how the photographs "are not pretty" but depict "mine own image." She also describes her appearance in racially derogatory language as "Esquimaux—Nigger—Burmese." The photographs in the White series are often considered to be more "authentic" portraits of Belle Greene—despite their staged studio backdrops—because they do not create a whitewashing effect with lighting or skin tone, as in the photographs by Theodore Marceau, the drawing by Paul Helleu, or the painting by Laura Coombs Hills. But perhaps Greene saw in that authenticity a visual trace of her mixed-race ancestry, leading her to racialize the images in her letter to Berenson.

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to White series, but she also sat for Marceau in May 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

BG to BB, 12/15/11 (176; likely reference to White series): “ I am sending you some photographs taken last June for your Xmas – If you don’t like them just tear them up but I am sure the “Esquimaux – Nigger – Burmese” one will appeal to you – I wish I had as many of you”

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180; likely reference to White series): “I am so glad, you beloved you, that you liked the photographs – As you say, they are mine own self, poor, indifferent and bad – I hope the smoking one particularly appealed to you”

Racist Language

The original quotes from Belle Greene’s letters compiled on this website occasionally contain racist stereotyping and slurs. The fact that Greene made derogatory comments about skin color cannot be so easily viewed as a negative statement on her perspectives. Passing is a complicated and nuanced practice and passing individuals found ways to maneuver in a world that perceived them as inferior because of their skin complexion. Belle Greene’s use of anti-Black racist words in some of her letters—including “darky” and the “n” word—could have been a way for her to avoid suspicion about her ancestry, as public figures who expressed sympathy for the African American community were often met with rumors that they must be hiding Black ancestry. Such rumors about Babe Ruth, for example, arose when he advocated for the African American community in the 1930s. Belle Greene’s racist language is difficult to comprehend and accept, but it does not simply mean she had appropriated the white supremacist ideology current in her day. This language could have been used as a strategy, as a racial performance of passing in Jim Crow America, though that does not dismiss the negative impact the language has had on readers in both Greene’s day and our own.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Waxed platinum print 24 x 16.9 cm (9 7/8 x 6 5/8 in.)

Princeton University Art Museum. The Clarence H. White Collection, assembled and organized by Professor Clarence H. White Jr., and given in memory of Lewis F. White, Dr. Maynard P. White Sr., and Clarence H. White Jr., the sons of Clarence H. White Sr. and Jane Felix White. x1983-446

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

Clarence H. White

Arguably the most famous photographs of Belle da Costa Greene were taken by the photographer Clarence H. White in 1911. There are nine known images of Greene by White, with prints preserved at the Morgan, I Tatti, and Princeton University Art Museum. Those at I Tatti were given to Bernard Berenson by Greene, who appears to make several references to them in her letters to Bernard. White was part of the circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291 (named for its Fifth Avenue address). Greene knew and corresponded with Stieglitz, attended exhibitions at 291 (acquiring a Matisse drawing and Steichen photographic print there), and was caricatured by the Mexican-American artist Marius de Zayas, who also caricatured Clarence White. According to art historian Anne McCauley, Belle Greene wore in these photographs "a new type of close-fitting hat that conveniently hid her revealingly African American hair" (116). The few quotes in her letters to Berenson that seem to reference the White series note how the photographs "are not pretty" but depict "mine own image." She also describes her appearance in racially derogatory language as "Esquimaux—Nigger—Burmese." The photographs in the White series are often considered to be more "authentic" portraits of Belle Greene—despite their staged studio backdrops—because they do not create a whitewashing effect with lighting or skin tone, as in the photographs by Theodore Marceau, the drawing by Paul Helleu, or the painting by Laura Coombs Hills. But perhaps Greene saw in that authenticity a visual trace of her mixed-race ancestry, leading her to racialize the images in her letter to Berenson.

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to White series, but she also sat for Marceau in May 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

BG to BB, 12/15/11 (176; likely reference to White series): “ I am sending you some photographs taken last June for your Xmas – If you don’t like them just tear them up but I am sure the “Esquimaux – Nigger – Burmese” one will appeal to you – I wish I had as many of you”

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180; likely reference to White series): “I am so glad, you beloved you, that you liked the photographs – As you say, they are mine own self, poor, indifferent and bad – I hope the smoking one particularly appealed to you”

Racist Language

The original quotes from Belle Greene’s letters compiled on this website occasionally contain racist stereotyping and slurs. The fact that Greene made derogatory comments about skin color cannot be so easily viewed as a negative statement on her perspectives. Passing is a complicated and nuanced practice and passing individuals found ways to maneuver in a world that perceived them as inferior because of their skin complexion. Belle Greene’s use of anti-Black racist words in some of her letters—including “darky” and the “n” word—could have been a way for her to avoid suspicion about her ancestry, as public figures who expressed sympathy for the African American community were often met with rumors that they must be hiding Black ancestry. Such rumors about Babe Ruth, for example, arose when he advocated for the African American community in the 1930s. Belle Greene’s racist language is difficult to comprehend and accept, but it does not simply mean she had appropriated the white supremacist ideology current in her day. This language could have been used as a strategy, as a racial performance of passing in Jim Crow America, though that does not dismiss the negative impact the language has had on readers in both Greene’s day and our own.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Platinum print Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

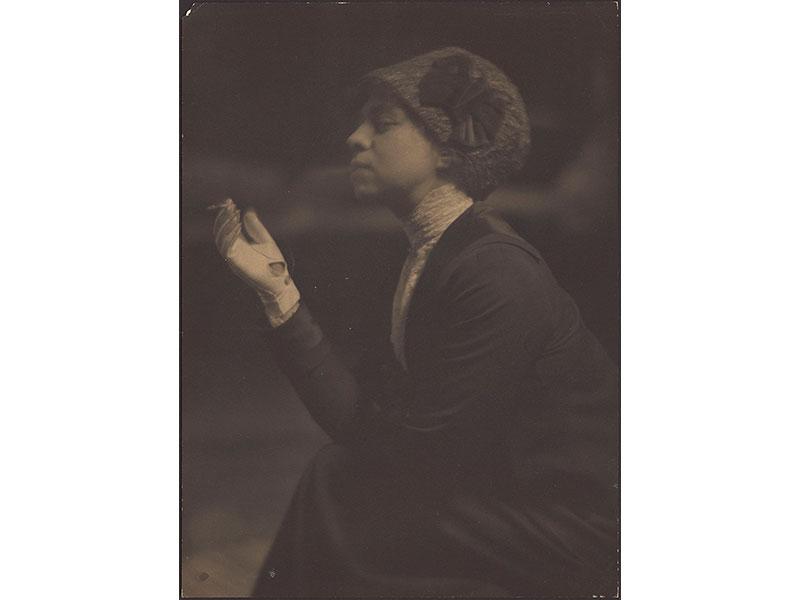

Clarence H. White

Arguably the most famous photographs of Belle da Costa Greene were taken by the photographer Clarence H. White in 1911. There are nine known images of Greene by White, with prints preserved at the Morgan, I Tatti, and Princeton University Art Museum. Those at I Tatti were given to Bernard Berenson by Greene, who appears to make several references to them in her letters to Bernard. White was part of the circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291 (named for its Fifth Avenue address). Greene knew and corresponded with Stieglitz, attended exhibitions at 291 (acquiring a Matisse drawing and Steichen photographic print there), and was caricatured by the Mexican-American artist Marius de Zayas, who also caricatured Clarence White. According to art historian Anne McCauley, Belle Greene wore in these photographs "a new type of close-fitting hat that conveniently hid her revealingly African American hair" (116). The few quotes in her letters to Berenson that seem to reference the White series note how the photographs "are not pretty" but depict "mine own image." She also describes her appearance in racially derogatory language as "Esquimaux—Nigger—Burmese." The photographs in the White series are often considered to be more "authentic" portraits of Belle Greene—despite their staged studio backdrops—because they do not create a whitewashing effect with lighting or skin tone, as in the photographs by Theodore Marceau, the drawing by Paul Helleu, or the painting by Laura Coombs Hills. But perhaps Greene saw in that authenticity a visual trace of her mixed-race ancestry, leading her to racialize the images in her letter to Berenson.

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to White series, but she also sat for Marceau in May 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

BG to BB, 12/15/11 (176; likely reference to White series): “ I am sending you some photographs taken last June for your Xmas – If you don’t like them just tear them up but I am sure the “Esquimaux – Nigger – Burmese” one will appeal to you – I wish I had as many of you”

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180; likely reference to White series): “I am so glad, you beloved you, that you liked the photographs – As you say, they are mine own self, poor, indifferent and bad – I hope the smoking one particularly appealed to you”

Racist Language

The original quotes from Belle Greene’s letters compiled on this website occasionally contain racist stereotyping and slurs. The fact that Greene made derogatory comments about skin color cannot be so easily viewed as a negative statement on her perspectives. Passing is a complicated and nuanced practice and passing individuals found ways to maneuver in a world that perceived them as inferior because of their skin complexion. Belle Greene’s use of anti-Black racist words in some of her letters—including “darky” and the “n” word—could have been a way for her to avoid suspicion about her ancestry, as public figures who expressed sympathy for the African American community were often met with rumors that they must be hiding Black ancestry. Such rumors about Babe Ruth, for example, arose when he advocated for the African American community in the 1930s. Belle Greene’s racist language is difficult to comprehend and accept, but it does not simply mean she had appropriated the white supremacist ideology current in her day. This language could have been used as a strategy, as a racial performance of passing in Jim Crow America, though that does not dismiss the negative impact the language has had on readers in both Greene’s day and our own.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Platinum print 8 7/8 × 5 3/8 in. (22.5 × 13.7 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; ARC 2821

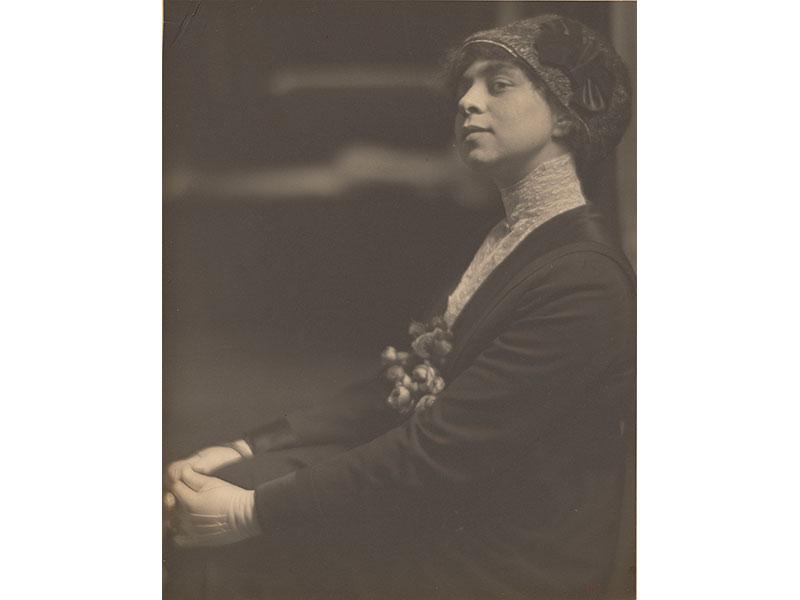

Clarence H. White

Arguably the most famous photographs of Belle da Costa Greene were taken by the photographer Clarence H. White in 1911. There are nine known images of Greene by White, with prints preserved at the Morgan, I Tatti, and Princeton University Art Museum. Those at I Tatti were given to Bernard Berenson by Greene, who appears to make several references to them in her letters to Bernard. White was part of the circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291 (named for its Fifth Avenue address). Greene knew and corresponded with Stieglitz, attended exhibitions at 291 (acquiring a Matisse drawing and Steichen photographic print there), and was caricatured by the Mexican-American artist Marius de Zayas, who also caricatured Clarence White. According to art historian Anne McCauley, Belle Greene wore in these photographs "a new type of close-fitting hat that conveniently hid her revealingly African American hair" (116). The few quotes in her letters to Berenson that seem to reference the White series note how the photographs "are not pretty" but depict "mine own image." She also describes her appearance in racially derogatory language as "Esquimaux—Nigger—Burmese." The photographs in the White series are often considered to be more "authentic" portraits of Belle Greene—despite their staged studio backdrops—because they do not create a whitewashing effect with lighting or skin tone, as in the photographs by Theodore Marceau, the drawing by Paul Helleu, or the painting by Laura Coombs Hills. But perhaps Greene saw in that authenticity a visual trace of her mixed-race ancestry, leading her to racialize the images in her letter to Berenson.

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to White series, but she also sat for Marceau in May 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

BG to BB, 12/15/11 (176; likely reference to White series): “ I am sending you some photographs taken last June for your Xmas – If you don’t like them just tear them up but I am sure the “Esquimaux – Nigger – Burmese” one will appeal to you – I wish I had as many of you”

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180; likely reference to White series): “I am so glad, you beloved you, that you liked the photographs – As you say, they are mine own self, poor, indifferent and bad – I hope the smoking one particularly appealed to you”

Racist Language

The original quotes from Belle Greene’s letters compiled on this website occasionally contain racist stereotyping and slurs. The fact that Greene made derogatory comments about skin color cannot be so easily viewed as a negative statement on her perspectives. Passing is a complicated and nuanced practice and passing individuals found ways to maneuver in a world that perceived them as inferior because of their skin complexion. Belle Greene’s use of anti-Black racist words in some of her letters—including “darky” and the “n” word—could have been a way for her to avoid suspicion about her ancestry, as public figures who expressed sympathy for the African American community were often met with rumors that they must be hiding Black ancestry. Such rumors about Babe Ruth, for example, arose when he advocated for the African American community in the 1930s. Belle Greene’s racist language is difficult to comprehend and accept, but it does not simply mean she had appropriated the white supremacist ideology current in her day. This language could have been used as a strategy, as a racial performance of passing in Jim Crow America, though that does not dismiss the negative impact the language has had on readers in both Greene’s day and our own.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Platinum print 9 7/8 × 7 3/4 in. (25.08 × 19.69 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; ARC 2822

Clarence H. White

Arguably the most famous photographs of Belle da Costa Greene were taken by the photographer Clarence H. White in 1911. There are nine known images of Greene by White, with prints preserved at the Morgan, I Tatti, and Princeton University Art Museum. Those at I Tatti were given to Bernard Berenson by Greene, who appears to make several references to them in her letters to Bernard. White was part of the circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291 (named for its Fifth Avenue address). Greene knew and corresponded with Stieglitz, attended exhibitions at 291 (acquiring a Matisse drawing and Steichen photographic print there), and was caricatured by the Mexican-American artist Marius de Zayas, who also caricatured Clarence White. According to art historian Anne McCauley, Belle Greene wore in these photographs "a new type of close-fitting hat that conveniently hid her revealingly African American hair" (116). The few quotes in her letters to Berenson that seem to reference the White series note how the photographs "are not pretty" but depict "mine own image." She also describes her appearance in racially derogatory language as "Esquimaux—Nigger—Burmese." The photographs in the White series are often considered to be more "authentic" portraits of Belle Greene—despite their staged studio backdrops—because they do not create a whitewashing effect with lighting or skin tone, as in the photographs by Theodore Marceau, the drawing by Paul Helleu, or the painting by Laura Coombs Hills. But perhaps Greene saw in that authenticity a visual trace of her mixed-race ancestry, leading her to racialize the images in her letter to Berenson.

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to White series, but she also sat for Marceau in May 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

BG to BB, 12/15/11 (176; likely reference to White series): “ I am sending you some photographs taken last June for your Xmas – If you don’t like them just tear them up but I am sure the “Esquimaux – Nigger – Burmese” one will appeal to you – I wish I had as many of you”

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180; likely reference to White series): “I am so glad, you beloved you, that you liked the photographs – As you say, they are mine own self, poor, indifferent and bad – I hope the smoking one particularly appealed to you”

Racist Language

The original quotes from Belle Greene’s letters compiled on this website occasionally contain racist stereotyping and slurs. The fact that Greene made derogatory comments about skin color cannot be so easily viewed as a negative statement on her perspectives. Passing is a complicated and nuanced practice and passing individuals found ways to maneuver in a world that perceived them as inferior because of their skin complexion. Belle Greene’s use of anti-Black racist words in some of her letters—including “darky” and the “n” word—could have been a way for her to avoid suspicion about her ancestry, as public figures who expressed sympathy for the African American community were often met with rumors that they must be hiding Black ancestry. Such rumors about Babe Ruth, for example, arose when he advocated for the African American community in the 1930s. Belle Greene’s racist language is difficult to comprehend and accept, but it does not simply mean she had appropriated the white supremacist ideology current in her day. This language could have been used as a strategy, as a racial performance of passing in Jim Crow America, though that does not dismiss the negative impact the language has had on readers in both Greene’s day and our own.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Platinum print 9 1/2 × 7 (24.2 × 17.8 cm)

Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs, Box 12, Folder 37

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

Clarence H. White

Arguably the most famous photographs of Belle da Costa Greene were taken by the photographer Clarence H. White in 1911. There are nine known images of Greene by White, with prints preserved at the Morgan, I Tatti, and Princeton University Art Museum. Those at I Tatti were given to Bernard Berenson by Greene, who appears to make several references to them in her letters to Bernard. White was part of the circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291 (named for its Fifth Avenue address). Greene knew and corresponded with Stieglitz, attended exhibitions at 291 (acquiring a Matisse drawing and Steichen photographic print there), and was caricatured by the Mexican-American artist Marius de Zayas, who also caricatured Clarence White. According to art historian Anne McCauley, Belle Greene wore in these photographs "a new type of close-fitting hat that conveniently hid her revealingly African American hair" (116). The few quotes in her letters to Berenson that seem to reference the White series note how the photographs "are not pretty" but depict "mine own image." She also describes her appearance in racially derogatory language as "Esquimaux—Nigger—Burmese." The photographs in the White series are often considered to be more "authentic" portraits of Belle Greene—despite their staged studio backdrops—because they do not create a whitewashing effect with lighting or skin tone, as in the photographs by Theodore Marceau, the drawing by Paul Helleu, or the painting by Laura Coombs Hills. But perhaps Greene saw in that authenticity a visual trace of her mixed-race ancestry, leading her to racialize the images in her letter to Berenson.

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to White series, but she also sat for Marceau in May 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

BG to BB, 12/15/11 (176; likely reference to White series): “ I am sending you some photographs taken last June for your Xmas – If you don’t like them just tear them up but I am sure the “Esquimaux – Nigger – Burmese” one will appeal to you – I wish I had as many of you”

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180; likely reference to White series): “I am so glad, you beloved you, that you liked the photographs – As you say, they are mine own self, poor, indifferent and bad – I hope the smoking one particularly appealed to you”

Racist Language

The original quotes from Belle Greene’s letters compiled on this website occasionally contain racist stereotyping and slurs. The fact that Greene made derogatory comments about skin color cannot be so easily viewed as a negative statement on her perspectives. Passing is a complicated and nuanced practice and passing individuals found ways to maneuver in a world that perceived them as inferior because of their skin complexion. Belle Greene’s use of anti-Black racist words in some of her letters—including “darky” and the “n” word—could have been a way for her to avoid suspicion about her ancestry, as public figures who expressed sympathy for the African American community were often met with rumors that they must be hiding Black ancestry. Such rumors about Babe Ruth, for example, arose when he advocated for the African American community in the 1930s. Belle Greene’s racist language is difficult to comprehend and accept, but it does not simply mean she had appropriated the white supremacist ideology current in her day. This language could have been used as a strategy, as a racial performance of passing in Jim Crow America, though that does not dismiss the negative impact the language has had on readers in both Greene’s day and our own.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Platinum print 9 13/16 × 7 5/16 (24.9 × 18.5 cm)

Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs, Box 12, Folder 37

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

Clarence H. White

Arguably the most famous photographs of Belle da Costa Greene were taken by the photographer Clarence H. White in 1911. There are nine known images of Greene by White, with prints preserved at the Morgan, I Tatti, and Princeton University Art Museum. Those at I Tatti were given to Bernard Berenson by Greene, who appears to make several references to them in her letters to Bernard. White was part of the circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291 (named for its Fifth Avenue address). Greene knew and corresponded with Stieglitz, attended exhibitions at 291 (acquiring a Matisse drawing and Steichen photographic print there), and was caricatured by the Mexican-American artist Marius de Zayas, who also caricatured Clarence White. According to art historian Anne McCauley, Belle Greene wore in these photographs "a new type of close-fitting hat that conveniently hid her revealingly African American hair" (116). The few quotes in her letters to Berenson that seem to reference the White series note how the photographs "are not pretty" but depict "mine own image." She also describes her appearance in racially derogatory language as "Esquimaux—Nigger—Burmese." The photographs in the White series are often considered to be more "authentic" portraits of Belle Greene—despite their staged studio backdrops—because they do not create a whitewashing effect with lighting or skin tone, as in the photographs by Theodore Marceau, the drawing by Paul Helleu, or the painting by Laura Coombs Hills. But perhaps Greene saw in that authenticity a visual trace of her mixed-race ancestry, leading her to racialize the images in her letter to Berenson.

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to White series, but she also sat for Marceau in May 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

BG to BB, 12/15/11 (176; likely reference to White series): “ I am sending you some photographs taken last June for your Xmas – If you don’t like them just tear them up but I am sure the “Esquimaux – Nigger – Burmese” one will appeal to you – I wish I had as many of you”

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180; likely reference to White series): “I am so glad, you beloved you, that you liked the photographs – As you say, they are mine own self, poor, indifferent and bad – I hope the smoking one particularly appealed to you”

Racist Language

The original quotes from Belle Greene’s letters compiled on this website occasionally contain racist stereotyping and slurs. The fact that Greene made derogatory comments about skin color cannot be so easily viewed as a negative statement on her perspectives. Passing is a complicated and nuanced practice and passing individuals found ways to maneuver in a world that perceived them as inferior because of their skin complexion. Belle Greene’s use of anti-Black racist words in some of her letters—including “darky” and the “n” word—could have been a way for her to avoid suspicion about her ancestry, as public figures who expressed sympathy for the African American community were often met with rumors that they must be hiding Black ancestry. Such rumors about Babe Ruth, for example, arose when he advocated for the African American community in the 1930s. Belle Greene’s racist language is difficult to comprehend and accept, but it does not simply mean she had appropriated the white supremacist ideology current in her day. This language could have been used as a strategy, as a racial performance of passing in Jim Crow America, though that does not dismiss the negative impact the language has had on readers in both Greene’s day and our own.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Platinum print 9 3/8 × 6 3/4 in. (23.8 × 17.1 cm)

Princeton University Art Museum, The Clarence H. White Collection, assembled and organized by Professor Clarence H. White Jr., and given in memory of Lewis F. White, Dr. Maynard P. White Sr., and Clarence H. White Jr., the sons of Clarence H. White Sr. and Jane Felix White; x1983-447

Clarence H. White

Arguably the most famous photographs of Belle da Costa Greene were taken by the photographer Clarence H. White in 1911. There are nine known images of Greene by White, with prints preserved at the Morgan, I Tatti, and Princeton University Art Museum. Those at I Tatti were given to Bernard Berenson by Greene, who appears to make several references to them in her letters to Bernard. White was part of the circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291 (named for its Fifth Avenue address). Greene knew and corresponded with Stieglitz, attended exhibitions at 291 (acquiring a Matisse drawing and Steichen photographic print there), and was caricatured by the Mexican-American artist Marius de Zayas, who also caricatured Clarence White. According to art historian Anne McCauley, Belle Greene wore in these photographs "a new type of close-fitting hat that conveniently hid her revealingly African American hair" (116). The few quotes in her letters to Berenson that seem to reference the White series note how the photographs "are not pretty" but depict "mine own image." She also describes her appearance in racially derogatory language as "Esquimaux—Nigger—Burmese." The photographs in the White series are often considered to be more "authentic" portraits of Belle Greene—despite their staged studio backdrops—because they do not create a whitewashing effect with lighting or skin tone, as in the photographs by Theodore Marceau, the drawing by Paul Helleu, or the painting by Laura Coombs Hills. But perhaps Greene saw in that authenticity a visual trace of her mixed-race ancestry, leading her to racialize the images in her letter to Berenson.

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to White series, but she also sat for Marceau in May 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

BG to BB, 12/15/11 (176; likely reference to White series): “ I am sending you some photographs taken last June for your Xmas – If you don’t like them just tear them up but I am sure the “Esquimaux – Nigger – Burmese” one will appeal to you – I wish I had as many of you”

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180; likely reference to White series): “I am so glad, you beloved you, that you liked the photographs – As you say, they are mine own self, poor, indifferent and bad – I hope the smoking one particularly appealed to you”

Racist Language

The original quotes from Belle Greene’s letters compiled on this website occasionally contain racist stereotyping and slurs. The fact that Greene made derogatory comments about skin color cannot be so easily viewed as a negative statement on her perspectives. Passing is a complicated and nuanced practice and passing individuals found ways to maneuver in a world that perceived them as inferior because of their skin complexion. Belle Greene’s use of anti-Black racist words in some of her letters—including “darky” and the “n” word—could have been a way for her to avoid suspicion about her ancestry, as public figures who expressed sympathy for the African American community were often met with rumors that they must be hiding Black ancestry. Such rumors about Babe Ruth, for example, arose when he advocated for the African American community in the 1930s. Belle Greene’s racist language is difficult to comprehend and accept, but it does not simply mean she had appropriated the white supremacist ideology current in her day. This language could have been used as a strategy, as a racial performance of passing in Jim Crow America, though that does not dismiss the negative impact the language has had on readers in both Greene’s day and our own.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Platinum print 9 1/2 × 5 1/2 in. (24.2 × 14 cm)

Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs, Box 12, Folder 37

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

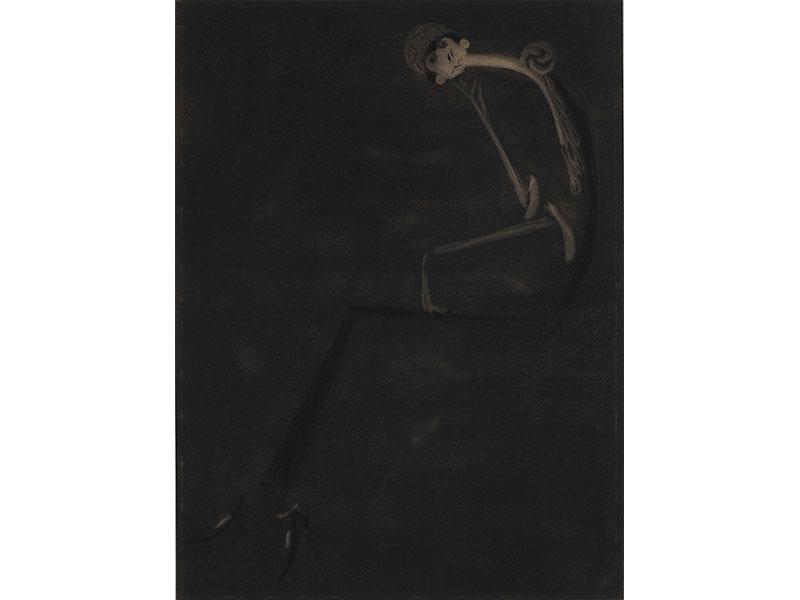

Clarence H. White

Arguably the most famous photographs of Belle da Costa Greene were taken by the photographer Clarence H. White in 1911. There are nine known images of Greene by White, with prints preserved at the Morgan, I Tatti, and Princeton University Art Museum. Those at I Tatti were given to Bernard Berenson by Greene, who appears to make several references to them in her letters to Bernard. White was part of the circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291 (named for its Fifth Avenue address). Greene knew and corresponded with Stieglitz, attended exhibitions at 291 (acquiring a Matisse drawing and Steichen photographic print there), and was caricatured by the Mexican-American artist Marius de Zayas, who also caricatured Clarence White. According to art historian Anne McCauley, Belle Greene wore in these photographs "a new type of close-fitting hat that conveniently hid her revealingly African American hair" (116). The few quotes in her letters to Berenson that seem to reference the White series note how the photographs "are not pretty" but depict "mine own image." She also describes her appearance in racially derogatory language as "Esquimaux—Nigger—Burmese." The photographs in the White series are often considered to be more "authentic" portraits of Belle Greene—despite their staged studio backdrops—because they do not create a whitewashing effect with lighting or skin tone, as in the photographs by Theodore Marceau, the drawing by Paul Helleu, or the painting by Laura Coombs Hills. But perhaps Greene saw in that authenticity a visual trace of her mixed-race ancestry, leading her to racialize the images in her letter to Berenson.

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to White series, but she also sat for Marceau in May 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

BG to BB, 12/15/11 (176; likely reference to White series): “ I am sending you some photographs taken last June for your Xmas – If you don’t like them just tear them up but I am sure the “Esquimaux – Nigger – Burmese” one will appeal to you – I wish I had as many of you”

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180; likely reference to White series): “I am so glad, you beloved you, that you liked the photographs – As you say, they are mine own self, poor, indifferent and bad – I hope the smoking one particularly appealed to you”

Racist Language

The original quotes from Belle Greene’s letters compiled on this website occasionally contain racist stereotyping and slurs. The fact that Greene made derogatory comments about skin color cannot be so easily viewed as a negative statement on her perspectives. Passing is a complicated and nuanced practice and passing individuals found ways to maneuver in a world that perceived them as inferior because of their skin complexion. Belle Greene’s use of anti-Black racist words in some of her letters—including “darky” and the “n” word—could have been a way for her to avoid suspicion about her ancestry, as public figures who expressed sympathy for the African American community were often met with rumors that they must be hiding Black ancestry. Such rumors about Babe Ruth, for example, arose when he advocated for the African American community in the 1930s. Belle Greene’s racist language is difficult to comprehend and accept, but it does not simply mean she had appropriated the white supremacist ideology current in her day. This language could have been used as a strategy, as a racial performance of passing in Jim Crow America, though that does not dismiss the negative impact the language has had on readers in both Greene’s day and our own.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Platinum print 8 7/8 × 5 3/8 in. (22.5 × 13.7 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; ARC 3275

Clarence H. White

Arguably the most famous photographs of Belle da Costa Greene were taken by the photographer Clarence H. White in 1911. There are nine known images of Greene by White, with prints preserved at the Morgan, I Tatti, and Princeton University Art Museum. Those at I Tatti were given to Bernard Berenson by Greene, who appears to make several references to them in her letters to Bernard. White was part of the circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291 (named for its Fifth Avenue address). Greene knew and corresponded with Stieglitz, attended exhibitions at 291 (acquiring a Matisse drawing and Steichen photographic print there), and was caricatured by the Mexican-American artist Marius de Zayas, who also caricatured Clarence White. According to art historian Anne McCauley, Belle Greene wore in these photographs "a new type of close-fitting hat that conveniently hid her revealingly African American hair" (116). The few quotes in her letters to Berenson that seem to reference the White series note how the photographs "are not pretty" but depict "mine own image." She also describes her appearance in racially derogatory language as "Esquimaux—Nigger—Burmese." The photographs in the White series are often considered to be more "authentic" portraits of Belle Greene—despite their staged studio backdrops—because they do not create a whitewashing effect with lighting or skin tone, as in the photographs by Theodore Marceau, the drawing by Paul Helleu, or the painting by Laura Coombs Hills. But perhaps Greene saw in that authenticity a visual trace of her mixed-race ancestry, leading her to racialize the images in her letter to Berenson.

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to White series, but she also sat for Marceau in May 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

BG to BB, 12/15/11 (176; likely reference to White series): “ I am sending you some photographs taken last June for your Xmas – If you don’t like them just tear them up but I am sure the “Esquimaux – Nigger – Burmese” one will appeal to you – I wish I had as many of you”

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180; likely reference to White series): “I am so glad, you beloved you, that you liked the photographs – As you say, they are mine own self, poor, indifferent and bad – I hope the smoking one particularly appealed to you”

Racist Language

The original quotes from Belle Greene’s letters compiled on this website occasionally contain racist stereotyping and slurs. The fact that Greene made derogatory comments about skin color cannot be so easily viewed as a negative statement on her perspectives. Passing is a complicated and nuanced practice and passing individuals found ways to maneuver in a world that perceived them as inferior because of their skin complexion. Belle Greene’s use of anti-Black racist words in some of her letters—including “darky” and the “n” word—could have been a way for her to avoid suspicion about her ancestry, as public figures who expressed sympathy for the African American community were often met with rumors that they must be hiding Black ancestry. Such rumors about Babe Ruth, for example, arose when he advocated for the African American community in the 1930s. Belle Greene’s racist language is difficult to comprehend and accept, but it does not simply mean she had appropriated the white supremacist ideology current in her day. This language could have been used as a strategy, as a racial performance of passing in Jim Crow America, though that does not dismiss the negative impact the language has had on readers in both Greene’s day and our own.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Platinum print 9 3/8 × 7 5/8 (23.9 × 19.2 cm)

Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs, Box 12, Folder 37.

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

Clarence H. White

Arguably the most famous photographs of Belle da Costa Greene were taken by the photographer Clarence H. White in 1911. There are nine known images of Greene by White, with prints preserved at the Morgan, I Tatti, and Princeton University Art Museum. Those at I Tatti were given to Bernard Berenson by Greene, who appears to make several references to them in her letters to Bernard. White was part of the circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291 (named for its Fifth Avenue address). Greene knew and corresponded with Stieglitz, attended exhibitions at 291 (acquiring a Matisse drawing and Steichen photographic print there), and was caricatured by the Mexican-American artist Marius de Zayas, who also caricatured Clarence White. According to art historian Anne McCauley, Belle Greene wore in these photographs "a new type of close-fitting hat that conveniently hid her revealingly African American hair" (116). The few quotes in her letters to Berenson that seem to reference the White series note how the photographs "are not pretty" but depict "mine own image." She also describes her appearance in racially derogatory language as "Esquimaux—Nigger—Burmese." The photographs in the White series are often considered to be more "authentic" portraits of Belle Greene—despite their staged studio backdrops—because they do not create a whitewashing effect with lighting or skin tone, as in the photographs by Theodore Marceau, the drawing by Paul Helleu, or the painting by Laura Coombs Hills. But perhaps Greene saw in that authenticity a visual trace of her mixed-race ancestry, leading her to racialize the images in her letter to Berenson.

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to White series, but she also sat for Marceau in May 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

BG to BB, 12/15/11 (176; likely reference to White series): “ I am sending you some photographs taken last June for your Xmas – If you don’t like them just tear them up but I am sure the “Esquimaux – Nigger – Burmese” one will appeal to you – I wish I had as many of you”

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180; likely reference to White series): “I am so glad, you beloved you, that you liked the photographs – As you say, they are mine own self, poor, indifferent and bad – I hope the smoking one particularly appealed to you”

Racist Language

The original quotes from Belle Greene’s letters compiled on this website occasionally contain racist stereotyping and slurs. The fact that Greene made derogatory comments about skin color cannot be so easily viewed as a negative statement on her perspectives. Passing is a complicated and nuanced practice and passing individuals found ways to maneuver in a world that perceived them as inferior because of their skin complexion. Belle Greene’s use of anti-Black racist words in some of her letters—including “darky” and the “n” word—could have been a way for her to avoid suspicion about her ancestry, as public figures who expressed sympathy for the African American community were often met with rumors that they must be hiding Black ancestry. Such rumors about Babe Ruth, for example, arose when he advocated for the African American community in the 1930s. Belle Greene’s racist language is difficult to comprehend and accept, but it does not simply mean she had appropriated the white supremacist ideology current in her day. This language could have been used as a strategy, as a racial performance of passing in Jim Crow America, though that does not dismiss the negative impact the language has had on readers in both Greene’s day and our own.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, ca. 1911–12

Digital positive from a gelatin dry plate negative

10 × 8 in. (25.4 × 20.3 cm)

Princeton University Art Museum, The Clarence H. White Collection, assembled and organized by Professor Clarence H. White Jr., and given in memory of Lewis F. White, Dr. Maynard P. White Sr., and Clarence H. White Jr., the sons of Clarence H. White Sr. and Jane Felix White; CHW NEG-1085.

Theodore C. Marceau

In 1911 Greene sat for the commercial photographer Theodore C. Marceau, presumably at his Fifth Avenue studio in New York. She posed in a studio chair before a painted backdrop, engrossed in a book. The image of her reading is not crisp enough to reveal whether it was a studio prop or a treasured volume Greene had brought with her to the sitting. There are four prints from the sitting that she sent to Bernard Berenson; no other prints are known to survive. Photographs from the Marceau series were, along with the De Meyer images, the most frequently reproduced images of Greene used in the mass media.

BG to BB, 5/15/11 (151; probable reference to the Marceau series): “I have been expecting my photographs every day to send you but they have not yet arrived, I hope you will like them. They are not any good but you know it if difficult to get a good picture of me – I have such a “wriggly” face”

BG to BB, 5/22-25/11 (155; probable reference to the Marceau series, as BG dated them May 1911; however, she also sat for White that year): “I am sending you by this mail some photographs I have recently had taken. If you find one you like, keep it and destroy the others. They are none of them very good but I am hard to photograph they all tell me”

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to Marceau series, but she also sat for White in June 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

Theodore C. Marceau (1859–1922)

Belle da Costa Greene (reading), May 1911

Gelatin silver print; 14 15/16 × 10 7/8 in. (38 × 27.7 cm)

Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs: Box 1 Friends (Large Format)

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

Theodore C. Marceau

Reproducing Theodore Marceau's portrait of Belle Greene reading.

“In the Public Eye, More or Less, at the Present Moment”

New York Daily Tribune, May 28, 1911

With reproduction of a photographic portrait of Belle da Costa Greene by Theodore C. Marceau (1859–1922)

Image provided by: Library of Congress, Washington, DC

Theodore C. Marceau

In 1911 Greene sat for the commercial photographer Theodore C. Marceau, presumably at his Fifth Avenue studio in New York. She posed in a studio chair before a painted backdrop, engrossed in a book. The image of her reading is not crisp enough to reveal whether it was a studio prop or a treasured volume Greene had brought with her to the sitting. There are four prints from the sitting that she sent to Bernard Berenson; no other prints are known to survive. Photographs from the Marceau series were, along with the De Meyer images, the most frequently reproduced images of Greene used in the mass media.

BG to BB, 5/15/11 (151; probable reference to the Marceau series): “I have been expecting my photographs every day to send you but they have not yet arrived, I hope you will like them. They are not any good but you know it if difficult to get a good picture of me – I have such a “wriggly” face”

BG to BB, 5/22-25/11 (155; probable reference to the Marceau series, as BG dated them May 1911; however, she also sat for White that year): “I am sending you by this mail some photographs I have recently had taken. If you find one you like, keep it and destroy the others. They are none of them very good but I am hard to photograph they all tell me”

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to Marceau series, but she also sat for White in June 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

Theodore C. Marceau (1859–1922)

Belle da Costa Greene (standing), May 1911

Gelatin silver print; 14 15/16 × 10 7/8 in. (38 × 27.7 cm)

Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs: Box 1 Friends (Large Format)

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

Theodore C. Marceau

In 1911 Greene sat for the commercial photographer Theodore C. Marceau, presumably at his Fifth Avenue studio in New York. She posed in a studio chair before a painted backdrop, engrossed in a book. The image of her reading is not crisp enough to reveal whether it was a studio prop or a treasured volume Greene had brought with her to the sitting. There are four prints from the sitting that she sent to Bernard Berenson; no other prints are known to survive. Photographs from the Marceau series were, along with the De Meyer images, the most frequently reproduced images of Greene used in the mass media.

BG to BB, 5/15/11 (151; probable reference to the Marceau series): “I have been expecting my photographs every day to send you but they have not yet arrived, I hope you will like them. They are not any good but you know it if difficult to get a good picture of me – I have such a “wriggly” face”

BG to BB, 5/22-25/11 (155; probable reference to the Marceau series, as BG dated them May 1911; however, she also sat for White that year): “I am sending you by this mail some photographs I have recently had taken. If you find one you like, keep it and destroy the others. They are none of them very good but I am hard to photograph they all tell me”

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to Marceau series, but she also sat for White in June 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

Theodore C. Marceau (1859–1922)

Belle da Costa Greene (seated), May 1911

Gelatin silver print; 14 15/16 × 10 7/8 in. (38 × 27.7 cm)

Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs: Box 1 Friends (Large Format)

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

Theodore C. Marceau

In 1911 Greene sat for the commercial photographer Theodore C. Marceau, presumably at his Fifth Avenue studio in New York. She posed in a studio chair before a painted backdrop, engrossed in a book. The image of her reading is not crisp enough to reveal whether it was a studio prop or a treasured volume Greene had brought with her to the sitting. There are four prints from the sitting that she sent to Bernard Berenson; no other prints are known to survive. Photographs from the Marceau series were, along with the De Meyer images, the most frequently reproduced images of Greene used in the mass media.

BG to BB, 5/15/11 (151; probable reference to the Marceau series): “I have been expecting my photographs every day to send you but they have not yet arrived, I hope you will like them. They are not any good but you know it if difficult to get a good picture of me – I have such a “wriggly” face”

BG to BB, 5/22-25/11 (155; probable reference to the Marceau series, as BG dated them May 1911; however, she also sat for White that year): “I am sending you by this mail some photographs I have recently had taken. If you find one you like, keep it and destroy the others. They are none of them very good but I am hard to photograph they all tell me”

BG to BB, 7/17/11 (161; possible reference to Marceau series, but she also sat for White in June 1911): “I am going to send you, in a day or two some photographs I had taken especially for you, and if these don’t please you I shall give up in despair – They are not pretty but I think they are “mine own image””

Theodore C. Marceau (1859–1922)

Belle da Costa Greene (leaning on chair), May 1911

Gelatin silver print; 14 15/16 × 10 7/8 in. (38 × 27.7 cm)

Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs: Box 1 Friends (Large Format)

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

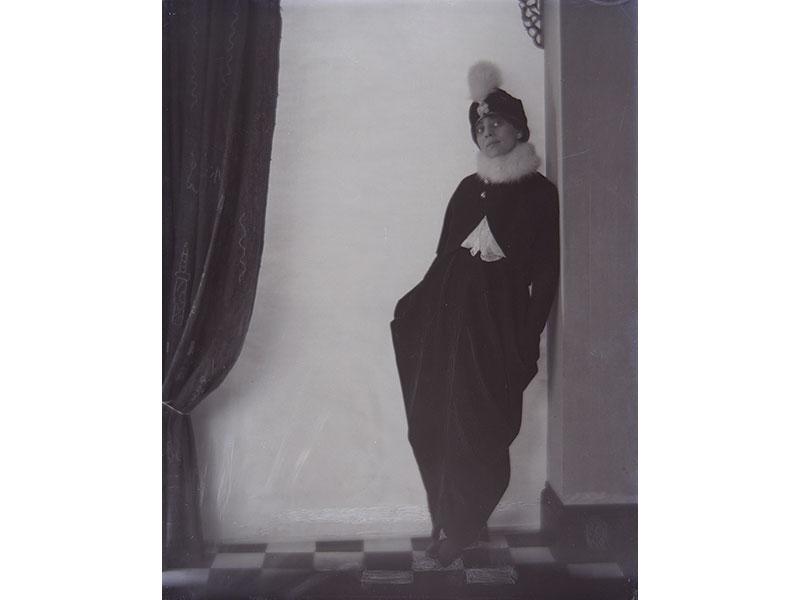

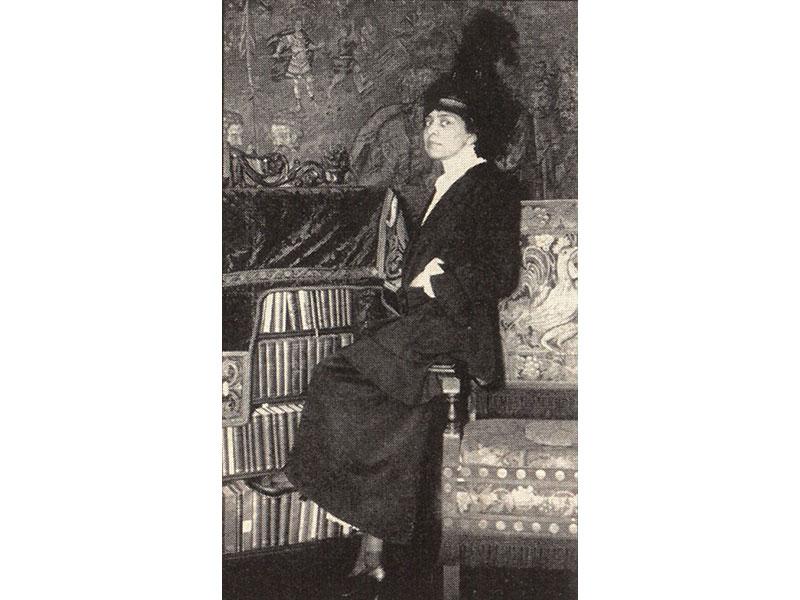

Adolph de Meyer

The French-born American photographer Adolph de Meyer was the object of Belle Greene's "immense" admiration in early 1912, when he exhibited his photographs in New York. Shortly thereafter he photographed Belle Greene in three different poses; she sent prints of these to Bernard Berenson and commented on them in her letters. They appeared to be some of her favorite images of herself: she had a "sneaking fondness" for them and "lots of people here are crazy about them." Reproductions of the image would appear in numerous newspaper articles and the most famous of the prints graced the cover of Heidi Ardizzone's 2007 biography of Belle Greene. Her comments to Berenson that the photographs depict her "as I am sometimes" and that they "really do look as I look in that get-up" indicates her approval of the likeness. One of the De Meyer photographs of Greene was exhibited at the Ritz Carlton in New York in January 1913.

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180): “Baron de Meyer, who is having a show here and whose work I admire immensely is going to take one of me on Thursday & if at all like me, I will send it to you – They are a messy lot, he and his wife, but he does good work – and for that reason we are on speaking terms”

BG to BB, 2/1/12 (181): “The de Meyer photographing was a failure the first time but he writes me today that the last sitting I gave him was very successful – as he is leaving for England within a fortnight I will ask him to send the prints directly to you – I hope they will be good – If you prefer me to sign them let me know by return & I will send them from here” B

G to BB, 2/6/12 (182): “I saw the de Meyer proofs yesterday they are interesting specimens of photography and like me as I am sometimes but as you have not very often seen me so you may not like them. However I will send you one or two and you can keep or destroy them as you like, (They each have a commercial value of $25.00!!!)”

BG to BB, 2/27/12 (185): “I sent you the de Meyer photographs today – Three of them – I had to cut off part of the mounting as it was too large to go through the mail. Will you please choose the one you like best, if any, and return the other two as they are very scarce – but, daarrling, if you really like and want them all do keep them. I am afraid you will find them rather “posey” but they really do look as I look in that get-up – It is an all black costume & everyone says I look deeply, darkly mysterious in it (but not beautiful) I do think it would be such a comfort to one’s self to be beautiful! Not to mention the treat it is to others.”

BG to BB, 3/19/12 (188): “You never told me how you liked my “de Meyer” photos, so I fear you don’t like them at all in which case send them back as lots of people here are crazy about them and beg me for them – but if you don’t like them neither do I any longer – of course they are very posey & all that – but they made me so very much better looking than I am. that I could not help having a sneaking fondness for them.”

BG to BB, 4/9/12 (190): “Have you not received my de Meyer photographs or do you dislike them so much that you even refuse to mention them?”

Adolph de Meyer (1868–1946)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1912

Villa I Tatti, The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

Adolph de Meyer

The French-born American photographer Adolph de Meyer was the object of Belle Greene's "immense" admiration in early 1912, when he exhibited his photographs in New York. Shortly thereafter he photographed Belle Greene in three different poses; she sent prints of these to Bernard Berenson and commented on them in her letters. They appeared to be some of her favorite images of herself: she had a "sneaking fondness" for them and "lots of people here are crazy about them." Reproductions of the image would appear in numerous newspaper articles and the most famous of the prints graced the cover of Heidi Ardizzone's 2007 biography of Belle Greene. Her comments to Berenson that the photographs depict her "as I am sometimes" and that they "really do look as I look in that get-up" indicates her approval of the likeness. One of the De Meyer photographs of Greene was exhibited at the Ritz Carlton in New York in January 1913.

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180): “Baron de Meyer, who is having a show here and whose work I admire immensely is going to take one of me on Thursday & if at all like me, I will send it to you – They are a messy lot, he and his wife, but he does good work – and for that reason we are on speaking terms”

BG to BB, 2/1/12 (181): “The de Meyer photographing was a failure the first time but he writes me today that the last sitting I gave him was very successful – as he is leaving for England within a fortnight I will ask him to send the prints directly to you – I hope they will be good – If you prefer me to sign them let me know by return & I will send them from here”

BG to BB, 2/6/12 (182): “I saw the de Meyer proofs yesterday they are interesting specimens of photography and like me as I am sometimes but as you have not very often seen me so you may not like them. However I will send you one or two and you can keep or destroy them as you like, (They each have a commercial value of $25.00!!!)”

BG to BB, 2/27/12 (185): “I sent you the de Meyer photographs today – Three of them – I had to cut off part of the mounting as it was too large to go through the mail. Will you please choose the one you like best, if any, and return the other two as they are very scarce – but, daarrling, if you really like and want them all do keep them. I am afraid you will find them rather “posey” but they really do look as I look in that get-up – It is an all black costume & everyone says I look deeply, darkly mysterious in it (but not beautiful) I do think it would be such a comfort to one’s self to be beautiful! Not to mention the treat it is to others.”

BG to BB, 3/19/12 (188): “You never told me how you liked my “de Meyer” photos, so I fear you don’t like them at all in which case send them back as lots of people here are crazy about them and beg me for them – but if you don’t like them neither do I any longer – of course they are very posey & all that – but they made me so very much better looking than I am. that I could not help having a sneaking fondness for them.”

BG to BB, 4/9/12 (190): “Have you not received my de Meyer photographs or do you dislike them so much that you even refuse to mention them?”

Adolph de Meyer (1868–1946)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1912

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 3276

Adolph de Meyer

The French-born American photographer Adolph de Meyer was the object of Belle Greene's "immense" admiration in early 1912, when he exhibited his photographs in New York. Shortly thereafter he photographed Belle Greene in three different poses; she sent prints of these to Bernard Berenson and commented on them in her letters. They appeared to be some of her favorite images of herself: she had a "sneaking fondness" for them and "lots of people here are crazy about them." Reproductions of the image would appear in numerous newspaper articles and the most famous of the prints graced the cover of Heidi Ardizzone's 2007 biography of Belle Greene. Her comments to Berenson that the photographs depict her "as I am sometimes" and that they "really do look as I look in that get-up" indicates her approval of the likeness. One of the De Meyer photographs of Greene was exhibited at the Ritz Carlton in New York in January 1913.

BG to BB, 1/9/12 (180): “Baron de Meyer, who is having a show here and whose work I admire immensely is going to take one of me on Thursday & if at all like me, I will send it to you – They are a messy lot, he and his wife, but he does good work – and for that reason we are on speaking terms”

BG to BB, 2/1/12 (181): “The de Meyer photographing was a failure the first time but he writes me today that the last sitting I gave him was very successful – as he is leaving for England within a fortnight I will ask him to send the prints directly to you – I hope they will be good – If you prefer me to sign them let me know by return & I will send them from here”

BG to BB, 2/6/12 (182): “I saw the de Meyer proofs yesterday they are interesting specimens of photography and like me as I am sometimes but as you have not very often seen me so you may not like them. However I will send you one or two and you can keep or destroy them as you like, (They each have a commercial value of $25.00!!!)”

BG to BB, 2/27/12 (185): “I sent you the de Meyer photographs today – Three of them – I had to cut off part of the mounting as it was too large to go through the mail. Will you please choose the one you like best, if any, and return the other two as they are very scarce – but, daarrling, if you really like and want them all do keep them. I am afraid you will find them rather “posey” but they really do look as I look in that get-up – It is an all black costume & everyone says I look deeply, darkly mysterious in it (but not beautiful) I do think it would be such a comfort to one’s self to be beautiful! Not to mention the treat it is to others.”

BG to BB, 3/19/12 (188): “You never told me how you liked my “de Meyer” photos, so I fear you don’t like them at all in which case send them back as lots of people here are crazy about them and beg me for them – but if you don’t like them neither do I any longer – of course they are very posey & all that – but they made me so very much better looking than I am. that I could not help having a sneaking fondness for them.”

BG to BB, 4/9/12 (190): “Have you not received my de Meyer photographs or do you dislike them so much that you even refuse to mention them?”

Adolph de Meyer (1868–1946)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1912

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 1664

The Delineator

Reproducing Theodore Marceau's portrait of Belle Greene reading.

"A Princess of the Realm of Books"

The Delineator, Vol. 79 (May 1912), p. 378

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

Chicago Daily Tribune

While the image of Belle Greene reaching for books is a fictional construction, the photograph of her in this article derives from one of the Theodore Marceau images (Belle da Costa Greene (seated)). Belle Greene overhead two men discussing a magazine reproduction of this article in 1914 and was disgusted by their conversation and the publicity about her.

BG to BB, 1/5/14 (371; likely reference to a reprint of this article in Form magazine): "It does make me sick – this damned newspaper publicity The other day sitting outside of the dining room for coffee at the Ritz, was a man with an open magazine in his hand – He was seated next to me, but not in our party – and I paid no attention to him naturally, nor should have, had I not heard him say to a man with him – “Morgan said she was the cleverest woman he ever met – I don’t think she’s much on looks do you? – Well I naturally pulled up my ears and turned to see the magazine & of whom he was gossiping when lo and behold my own portrait stared straight at me – I was furious! It was a thing called Form which I never heard of in my whole life before. It's really too disgusting to be discussed in the foyer of an hotel just as if one were an actorine."

“‘The Cleverest Girl I Know,’ Says J. Pierpont Morgan,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 11, 1912

Theodore Marceau

Reproducing Theodore Marceau's portrait of Belle Greene seated.

"Clever Girl Who Acts as Librarian to Multi-Millionaire. Miss Green [sic] Pays "£8,400 for a Single Book."

Penny Illustrated Paper, October 5, 1912

William Rothenstein

English artist Sir William Rothenstein (1872–1945), best known for his portraits, met Belle da Costa Greene in late 1911, when she told Berenson he was drawing "a pastel of [her] head." By February 1912 he had finished two drawings of Greene and exhibited the pastel in Boston; Greene "did not recognize [herself]" in the drawing, despite Rothenstein's claim of its great success. Elsewhere she described the portrait as "a combination of a Buddha – a suffragette and Jeanne d’Arc." These descriptions seem to relate to this drawing, which was given to the Morgan in 1956 by Belle Greene's successor as director of the Pierpont Morgan Library, Frederick B. Adams, Jr., who had apparently been given the drawing.

BG to BB, 12/12/11 (175): “I met your artist Rothenstein a day or two after he landed here at a dinner, & have seen him several times since. He is doing a pastel of my head – I have not seen it yet but hope it will be worth preserving – He is a most interesting chap and I liked him immensely Why didn’t you give him a letter to me instead of to all the fools of the world – To put that real man up against “the” Lydig, Kahns & Flowerdales! Poor child, I laughed until he grew cross & then I sympathized with him – However I trust he will do better in Boston & when he gets back here I will shake up one or two people for him”

BG to BB, 2/6/12 (182): “Rothenstein finished a second drawing of me the other day which I understand he is going to present to me in which case I will send it to you – He thinks the pastel a great success but I do not recognize myself in it at all. He exhibited it in Boston & says he got lots of orders on the strength of it but God alone knows why”

BG to BB, 2/13/12 (183): “I enclose a note from your friend Rothenstein which I think is very nice and hope, if you see him, you will tell him how much I liked him as I neglected to write the same myself. If you like I will send you the pastel along with the de Meyer photographs or else I will keep it here until the fall when you come and if you like it you can take it back with you – It looks to me like a combination of a Buddha – a suffragette and Jeanne d’Arc – But you shall judge for yourself what you think of it – I like the last drawing he made of me and which I will have photographed for you”

BG to BB, 2/11/13 (226): “he [Mabel Dodge’s husband] expressed himself as much relieved to find that I did not look like Rothenstein’s portrait of me”

William Rothenstein (1872–1945)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1912

Red and black chalk on blue-gray paper

12 1/4 x 9 7/16 inches (31.1 x 24 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1956.5. Gift of Frederick B. Adams, Jr., 1956.

Paul Helleu