J. Pierpont Morgan's Library: Building the Bookman's Paradise

Take a Virtual Tour

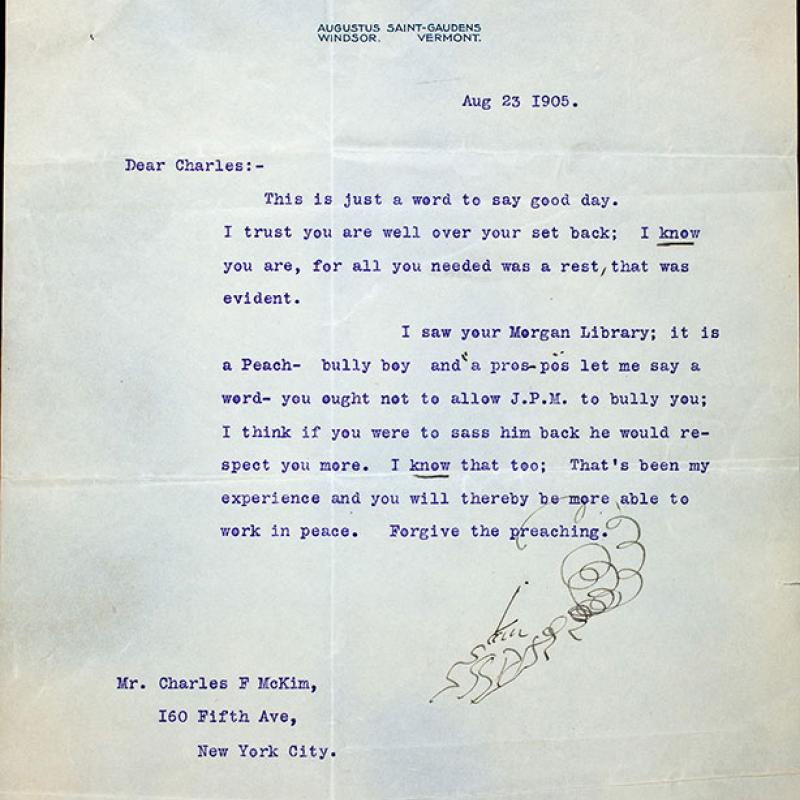

In 1902 the American financier and collector J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) commissioned architect Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909) of the firm McKim, Mead & White to design a freestanding library next to his home on East 36th Street. This exhibition traces the design and construction of Morgan’s Library and honors the designers, tradespeople, artists, and builders who created it more than a century ago. It also celebrates the recent completion of an exterior restoration and enhancement of the landmark building, which now anchors the campus of the Morgan Library & Museum.

In 1908 an unnamed correspondent from the London Times visited the finished Library and wrote the first public account of its lavish interiors and the splendid rare books and manuscripts held within. “The Bookman’s Paradise exists,” the reporter announced, “and I have seen it. . . . I have entered the most carefully, jealously guarded treasure-house in the world, and nothing in it has been hidden from me.” Today, the “bookman’s paradise” belongs to all of us.

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library: Building the Bookman’s Paradise is made possible by generous support from the Lucy Ricciardi Family Exhibition Fund, the Parker Gilbert Fund, the Arthur F. and Alice E. Adams Charitable Foundation, the Achelis & Bodman Foundation, Mrs. Oscar de la Renta, and Mr. G. Scott Clemons and Ms. Karyn Joaquino, with assistance from Jessie Schilling and the Franklin Jasper Walls Lecture Fund.

Who Built the Bookman's Paradise?

ARCHITECTS

McKim, Mead & White

LEAD ARCHITECT

Charles Follen McKim

PROJECT STAFF

Burt Fenner, William Mitchell Kendall, George F. Martin, Gustave E. Wolters

DRAFTERS

Will S. Aldrich, Ernest Isbell Barott, William Mitchell Kendall, August Reuling, William J. Sayward, Gorham Phillips Stevens, Thomas Wight

GENERAL CONTRACTOR

Charles T. Wills (A. H. Tyson, superintendent)

EXTERIOR MARBLE CONTRACTOR

Robert C. Fisher Co. (Edward B. Tompkins, president)

ADVISERS TO ARCHITECT

E. Gordon Duff, Daniel Chester French, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Waldo Story, Sir Aston Webb

ADVISERS TO CLIENT

Junius Spencer Morgan II, Herbert L. Satterlee, and Belle da Costa Greene (librarian)

ANTIQUE ELEMENTS

Stefano Bardini, Riccardo Nobili

ARCHITECTURAL RENDERINGS

Hughson Hawley, Henry Bacon

BATHROOM FITTINGS

The Meyer-Sniffen Co., Ltd.

BLUESTONE SIDEWALK

Augustus Meyers

BRONZE AND IRONWORK

Wm. H. Jackson Company (Joseph W. Lautry, A. Barr)

BUILDING SITE ENCLOSURES

Kidd, McKay & Henschen; A. Milton Napier; Norcross Brothers

CABINETRY

Library Bureau (Nathaniel B. H. Parker)

CARPENTRY

Kidd, McKay & Henschen

CEILING PAINTING (DECORATIVE)

H. Siddons Mowbray, James Wall Finn

CEILING SETTING T. D.

Wadelton

CEILING VAULTING

R. Guastavino Co.

CHIMNEY RECONSTRUCTION

John Whitley

CIRCULAR STAIRWAY

William H. Atkinson Co.

CONSULTING ENGINEER

Alfred R. Wolff

DEMOLITION

C. H. Southard

DOORS (INTERIOR)

The Hiss Company (H. T. Blodgett)

ELECTRICAL FIXTURES

Edward F. Caldwell & Co.

ELECTRICAL WORK

Johnston Livingston, Jr. & Co. (Albin Gustafson)

ELEVATOR

Otis Elevator Company (Frederick E. Town)

EXCAVATION

John Slattery

FENCE

Wm. H. Jackson Company, James Sinclair & Company, Robert C. Fisher & Co.

FIREPROOFING

John W. Rapp

FLOOR TILING

Wm. H. Jackson Company

FLOORING

G. W. Koch & Son; Kidd, McKay & Henschen

FOUNDATIONS

Charles T. Wills FURNITURE Cowtan and Sons (A. Barnard Cowtan)

GLASS

Sutphen & Myer

GRANITE

M. McGrath & Co.

GRANOLITHIC PAVING

R. H. Jaffray & Co.

GUARDRAILS

Jno. Williams

GUTTERS

John Seton

HARDWARE

Yale & Towne Manufacturing Company

HEATING

Walker & Pratt Manufacturing Co. (C. Frank Whittemore)

HEATING REGISTERS

Tuttle & Bailey Mfg Co.

LANDSCAPE DESIGN

Beatrix Jones (later Farrand)

MARBLE COLUMNS AND BENCHES

Eugene Glaenzer, Charles Mannheim, Alessandro Marcocchia, George Williams

MASONRY

Charles T. Wills

MOSAIC WALL TILE

Robert C. Fisher & Co.

PLASTER AND MODELING

Herman Beitz, Buehler & Lauter, Piccirilli Brothers

PLUMBING

W. H. Spelman

ROOFING

Charles T. Wills

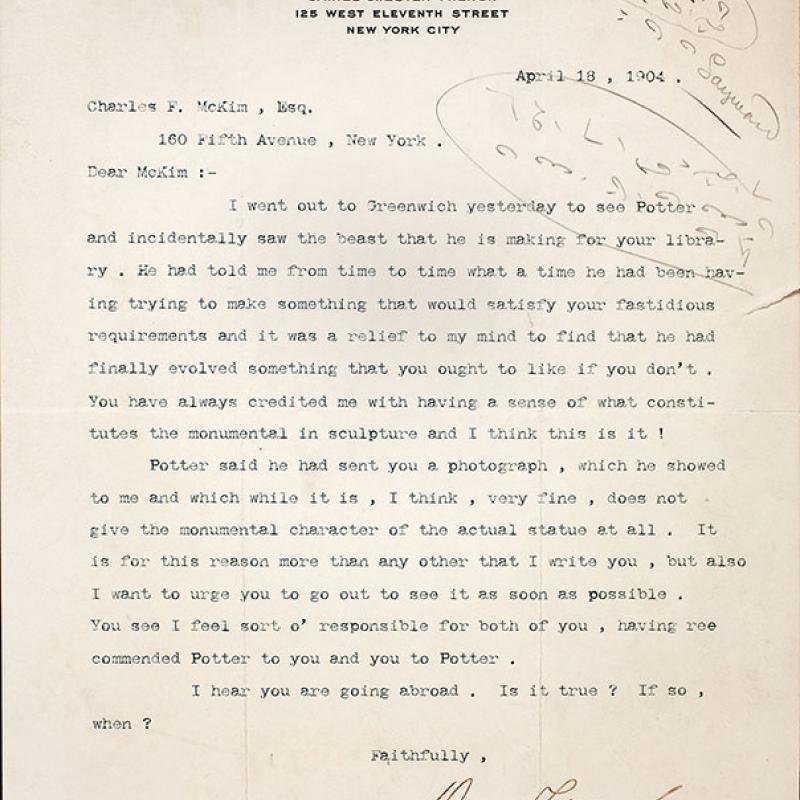

SCULPTURE

Andrew O’Connor, Edward Clark Potter, Adolph Weinman

SECURITY SYSTEM

Holmes Electric Protective Co.

SHADES

W. & J. Sloane

SHUTTERS

James G. Wilson Manufacturing Co.

SKYLIGHTS

John Seton

STAINED AND LEADED GLASS INSTALLATION

Cottier & Co.

STONE CARVING

Robert C. Fisher & Co. (exterior), Piccirilli Brothers (tympanum)

STONE SETTING

William Angus

STONE SUPPLIER

John M. Ross

STRUCTURAL STEEL

James E. Brooks Co.

SURVEYING

Francis W. Ford

VACUUM SWEEPING SYSTEM

David T. Kenney Co.

VAULT LINING AND DOOR

Herring-Hall- Marvin Safe Co.

WALL COVERINGS

John and James Dobson via Cowtan and Sons (supplier), William Baumgarten & Co. (installation)

WINDOW GUARDS

The Lobel-Andrews Company

We also acknowledge the many additional tradespeople and laborers, their names unknown to us today, who contributed in countless ways to the Library building, as well as the many who have worked to preserve and maintain it for more than a century.

Hughson Hawley (1850–1936) for McKim, Mead & White, J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1902. Watercolor. The Morgan Library & Museum; 1958.24.

Overview

The Facade

Situated on an urban residential block, J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library appears strikingly distinct yet surprisingly at home. Architect Charles Follen McKim drew on Italian Renaissance precedents to design a contemporary American building that conveyed power and permanence, intimacy and grandeur. “Above all,” he told his client, “we are desirous that the design shall represent your views and reflect your judgment, in order that it may become a worthy monument to your munificence and public spirit.”

The building was complete by 1906, and Morgan was satisfied. Daniel Chester French, the prominent sculptor, stopped by to see it and wrote to reassure the exhausted McKim: “Of course Mr. Morgan likes his library. Who would dare not to?”

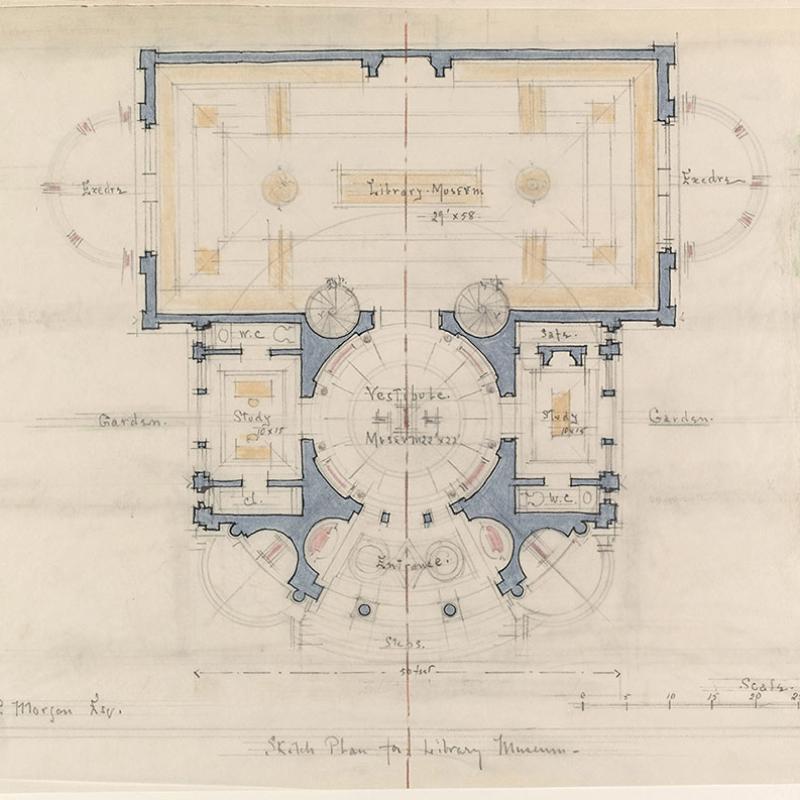

Plan View of Warren's Unbuilt Library-museum

There are no records of Warren’s discussions with Morgan about the program for the new Library, but this drawing suggests that Warren and Charles Follen McKim received similar instructions. Both Warren’s unbuilt design and McKim’s realized plan include a central rotunda, a grand library space, and two smaller offices. Though Warren’s drawings reference a “Library-Museum,” Morgan ultimately clarified that his new building would most emphatically be a library rather than a “picture gallery.”

Whitney Warren (1864–1943)

For J. P. Morgan Esq. / Sketch Plan for Library Museum, before March 1902

Graphite, pen and black ink, blue and yellow watercolor, and red and green crayon

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Mrs. William Greenough; 1943-51-334

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum / Art Resource, NY

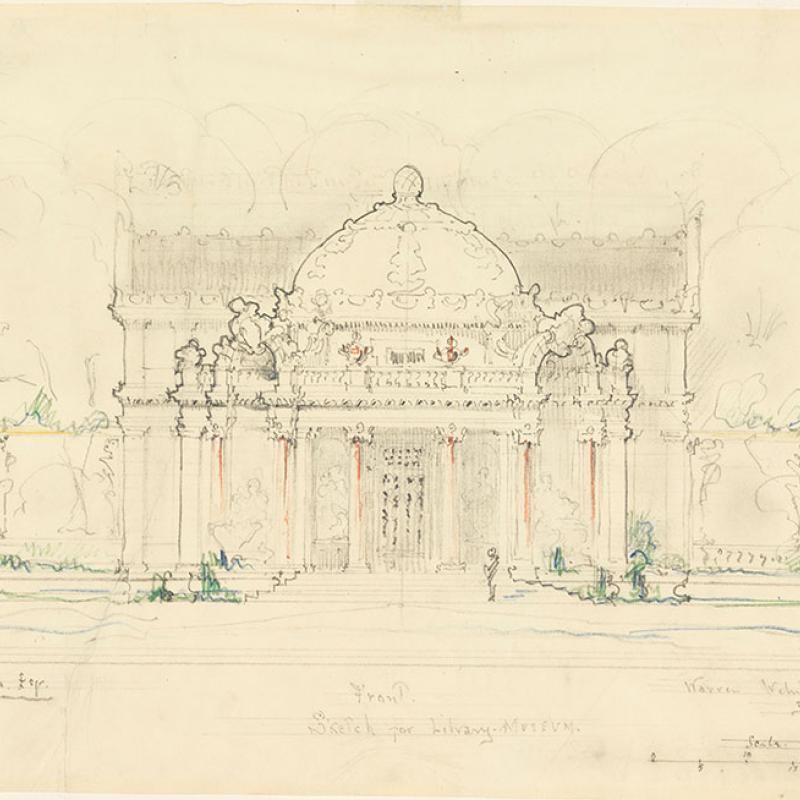

Whitney Warren’s Sketch for a "library-museum"

As commodore of the New York Yacht Club, Morgan served on the committee that selected architect Whitney Warren’s ambitious designs for the new clubhouse that opened in 1901 on West 44th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. It may have been around that time that Morgan asked Warren to draw up these undated plans for his Library. There is no record of Morgan’s response; we only know that he chose not to engage Warren and turned instead to Charles Follen McKim.

Whitney Warren (1864–1943)

For J. P. Morgan / Front / Sketch for Library-Museum, before March 1902

Graphite and colored pencil

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Mrs. William Greenough; 1943-51-401

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum / Art Resource, NY

Warren's Refined Design

In this more formal elevation, Warren proposed an ornate Beaux-Arts-inspired “Library-Museum,” its entrance flanked by figures representing art and wisdom, water gushing from open-mouthed lions at the pedestals’ feet. Morgan did not pursue Warren’s designs and offered the commission to Charles Follen McKim. Warren was displeased, and he let McKim know it. Warren would visit Morgan in the completed Library in 1908 but apparently held his grudge. As late as 1930 he stated publicly that McKim had taken the Library from him and boasted that he had evened matters by securing a commission McKim, Mead & White had also sought: Grand Central Terminal.

Whitney Warren (1864–1943)

Front Elevation / Proposed Library-Museum for J. Pierpont Morgan Esq. New York, before March 1902

Graphite

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Mrs. William Greenough; 1943-51-332

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum / Art Resource, NY

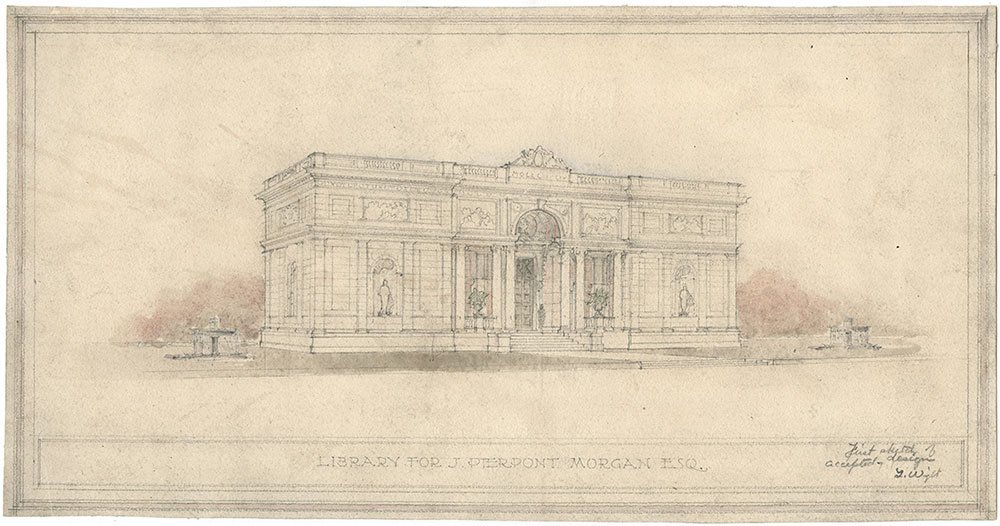

The Approved Design

This drawing, marked “First sketch of accepted design,” was made not by the lead architect, Charles Follen McKim, but by his twenty-seven-year-old employee Thomas Wight. This was not unusual: McKim was known for relying on the firm’s studio drafters while providing strong design leadership.

As a teenager newly arrived from Nova Scotia in the 1890s, Wight had answered an advertisement for a “boy” to work with McKim, Mead & White in Boston. “I want the job, but I don’t want to be a boy,” he said, insisting there be room for advancement. There was. Wight left the firm before the Library was completed to establish his own successful architectural practice in Kansas City, where he would design the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Thomas Wight (1874–1949) for McKim, Mead & White

Library for J. Pierpont Morgan, Esq., ca. August 1902

Graphite with wash

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library: the Architects' Model

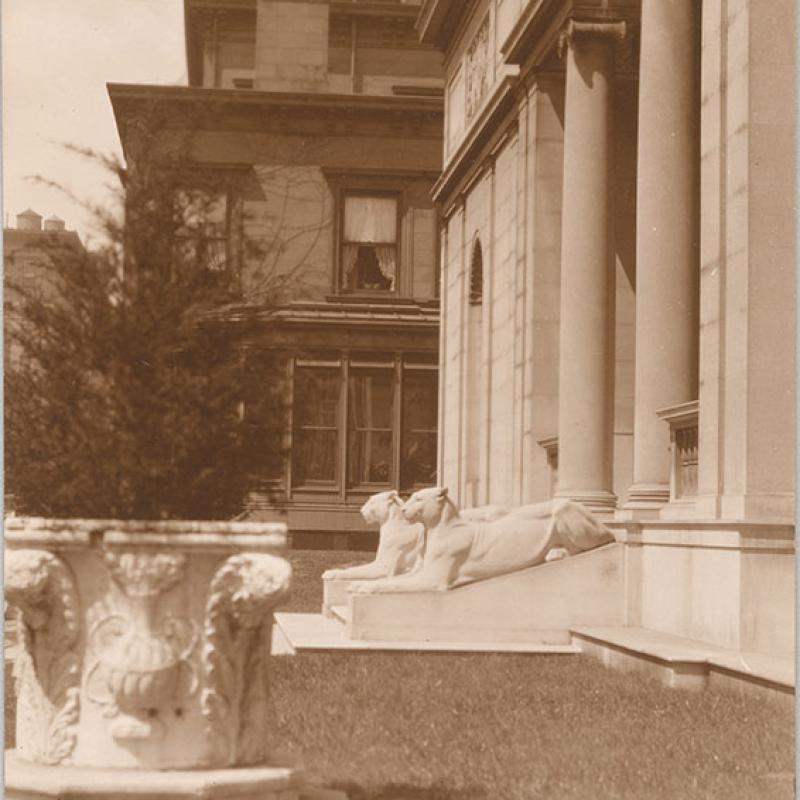

After Morgan engaged McKim, Mead & White to design his Library in 1902, lead architect Charles Follen McKim developed several proposals (including one with a tall cupola) before arriving at the plan embodied in this plaster maquette. The model differs only in modest respects from the completed building. The two arched niches would remain empty; no sculptures were ever installed. Notably missing here are the marble lionesses that Edward Clark Potter would sculpt to flank the entry.

Maquette for J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, designed by McKim, Mead & White, ca. 1904 or later

Plaster

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 2646

A Vision for Morgan's Library

In August 1902, as design development was in its final stages, Charles Follen McKim commissioned Hughson Hawley, a well-regarded architectural renderer, to create this evocative watercolor of the approved design. With its depictions of blue skies above, horses and carriages passing by, and fashionably dressed New Yorkers milling about, the drawing anticipated the way the completed building would appear in its residential context.

Hughson Hawley (1850–1936) for McKim, Mead & White

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1902

Watercolor

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1958.24

Inside the Bookman's Paradise

This longitudinal section, created late in the design process, depicts the Library’s three principal rooms. At left is the West Room (Morgan’s study), with its low bookshelves and space for the display of artworks. At center is the Rotunda, the main hall, with its highly decorated domed ceiling and ring of pilasters. At right is the East Room, the grand space in which much of Morgan’s book collection would be prominently displayed. A dotted line traces the position of a spiral staircase that begins at the cellar level.

The doorway at the immediate center leads to the North Room, which would become the office of Morgan’s librarian, Belle da Costa Greene. The antique stone doorframe is engraved with the motto Soli Deo Honor et Gloria (Glory and honor to God alone).

McKim, Mead & White (drafter unknown)

Library for J. P. Morgan Esq., Longitudinal Section, Looking North, 1905

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

The Bookman

When he was a boy growing up in New England, J. Pierpont Morgan began collecting autographs of famous men— a popular pastime of the day. Before he turned fifty, he commissioned a catalogue of his growing personal library, which now encompassed much more than autographs. But it was only after he turned sixty that he started making purchases on a prodigious scale. By the time of his death in 1913 at age seventy-five, he was one of the world’s elite collectors of rare books and manuscripts.

What allowed Morgan to create such a magnificent library? He benefited from economic privilege and astute family guidance. As a young man, he studied in Switzerland and Germany before returning to New York to embark upon his financial career. His father and nephew, both named Junius and both committed bibliophiles, introduced him to the practice of acquiring books as treasured objects more so than as texts for reading. Thus equipped, Morgan amassed the collection that would fill his “bookman’s paradise.”

J. Pierpont Morgan, ca. 1860s. Photo: Disdéri & Co., Paris.

The Young Reader

As a fourteen-year-old student at Boston’s English High School, the future bibliophile composed this essay on the value of reading. In impeccable cursive, young Morgan (known as Pierpont to family and friends) pronounced most novels “useless trash” but allowed that “well written and true stories” can teach us “how to treat other persons with proper reverence and respect.” He concluded, “How necessary, yes, how important it is that all should read for their well-being and happiness.”

J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913)

“Reading”

High school essay with instructor’s notes in pencil, 2 January 1852

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1196

"Reading", p. 2

As a fourteen-year-old student at Boston’s English High School, the future bibliophile composed this essay on the value of reading. In impeccable cursive, young Morgan (known as Pierpont to family and friends) pronounced most novels “useless trash” but allowed that “well written and true stories” can teach us “how to treat other persons with proper reverence and respect.” He concluded, “How necessary, yes, how important it is that all should read for their well-being and happiness.”

J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913)

“Reading”

High school essay with instructor’s notes in pencil, 2 January 1852

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1196

"Reading", p. 3

As a fourteen-year-old student at Boston’s English High School, the future bibliophile composed this essay on the value of reading. In impeccable cursive, young Morgan (known as Pierpont to family and friends) pronounced most novels “useless trash” but allowed that “well written and true stories” can teach us “how to treat other persons with proper reverence and respect.” He concluded, “How necessary, yes, how important it is that all should read for their well-being and happiness.”

J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913)

“Reading”

High school essay with instructor’s notes in pencil, 2 January 1852

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1196

"Reading", p. 4

As a fourteen-year-old student at Boston’s English High School, the future bibliophile composed this essay on the value of reading. In impeccable cursive, young Morgan (known as Pierpont to family and friends) pronounced most novels “useless trash” but allowed that “well written and true stories” can teach us “how to treat other persons with proper reverence and respect.” He concluded, “How necessary, yes, how important it is that all should read for their well-being and happiness.”

J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913)

“Reading”

High school essay with instructor’s notes in pencil, 2 January 1852

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1196

Autograph Collecting

Fourteen-year-old Morgan received this pocket diary as a Christmas gift from his father. In it, the young Morgan faithfully recorded his daily activities, including his early efforts to build an autograph collection. On 3 October 1851, he noted that he had “received some letters from distinguished men.” The next day, he secured the autographs of two of his grandfather’s acquaintances: Jared Sparks, president of Harvard College, and Edward Everett, a prominent educator and politician.

J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913)

Diary, 1851

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1196

A Library Without Books

During the 1880s, the Manhattan home of J. Pierpont Morgan and his second wife, Frances (Fanny), was featured in a lavish volume depicting the domestic interiors of wealthy Americans. This photograph shows their home library, which was luxuriously outfitted by decorator Christian Herter and illuminated with Thomas Edison’s new electric lighting. But the library is curiously short on books. Only a sliver of low shelving is visible to the right of the windows. In the freestanding library Morgan would commission two decades later, fine volumes would be very much in evidence.

The house pictured here, later demolished, was located at the corner of 36th Street and Madison Avenue, on the site of the building you are in now.

“Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library”

Modern reproduction of a photograph published in Artistic Houses: Being a Series of Interior Views of a Number of the Most Beautiful and Celebrated Homes in the United States; With a Description of the Art Treasures Contained Therein, vol. 1

New York: D. Appleton, 1883

The Morgan Library & Museum; PML 127667

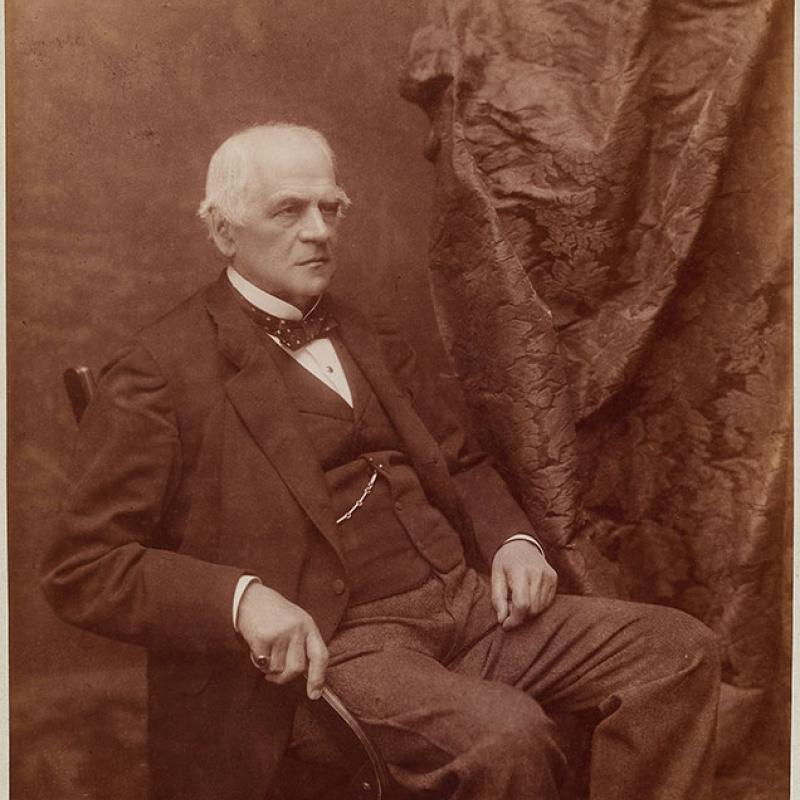

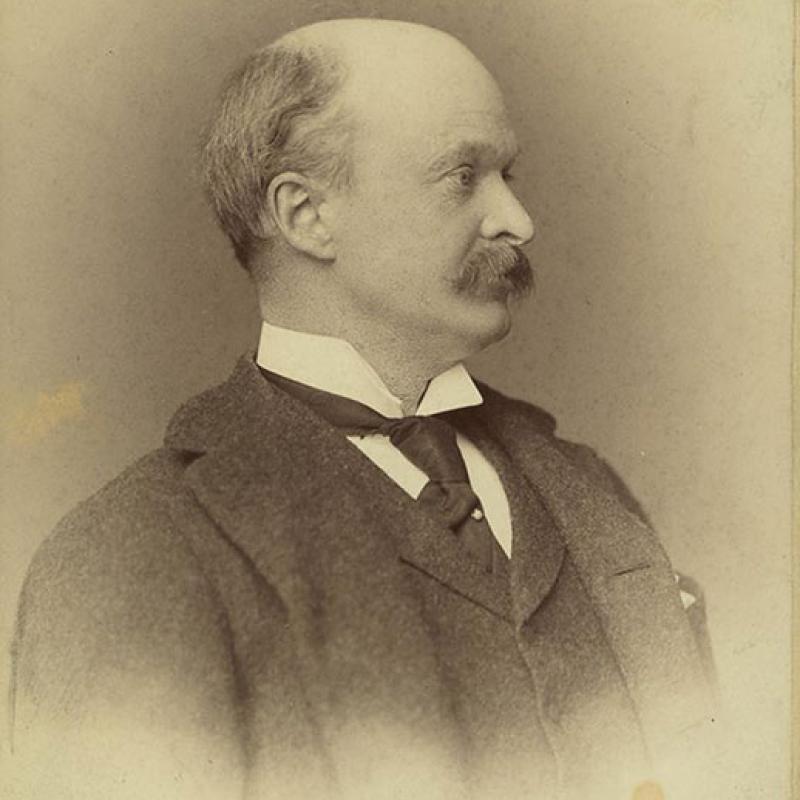

Morgan's Father: Banker and Bookman

Head of a successful London-based merchant-banking firm, Junius Spencer Morgan (1813–1890) took a strong hand in directing his son Pierpont’s early career on Wall Street. Junius was also an avid collector of books and manuscripts. When Junius died of injuries sustained in a carriage accident in 1890, Pierpont inherited $15 million (equivalent to about $463 million today) and found himself well positioned to build his business, as well as to devote increasingly large sums to the acquisition of rare books and artworks.

H. S. Mendelssohn, London

Junius Spencer Morgan, undated (before 1890)

Albumen print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 3286

J. Pierpont Morgan, Rising Bibliophile

By the 1880s—about the time of this portrait—Morgan had assembled a fine home library comprising titles typically found on his peers’ bookshelves. But alongside modern editions of such authors as Charles Dickens and Edward Bulwer-Lytton were several items that stood out, among them autographs of the signers of the US Declaration of Independence, a handwritten letter by the poet Robert Burns, and a copy of the so-called Eliot Indian Bible, the first translation of the Old and New Testaments into an Indigenous American language.

By the 1890s Morgan was regularly visiting New York and London bookdealers and seeking out authors’ manuscripts and first editions—and even his first Gutenberg Bible.

H. S. Mendelssohn, London

J. Pierpont Morgan, undated (before 1890)

Albumen print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 3287

Junius S. Morgan II: Nephew and Adviser

Junius Spencer Morgan II (1867–1932), son of J. Pierpont Morgan’s sister Sarah, began collecting rare books while he was in his teens and eventually built a fine collection of the ancient Roman poet Virgil’s works. An indifferent financier and ardent bibliophile, Junius became his uncle’s adviser and de facto librarian, exerting an outsize influence on the nature and scale of Pierpont’s acquisitions. It was Junius who guided Pierpont in his en bloc purchases of other collections, conferred with architect Charles Follen McKim during the Library’s design and construction, and—importantly—introduced Pierpont to Belle da Costa Greene, the librarian who would ultimately displace Junius as manager of all matters related to Pierpont’s books and manuscripts.

Gainsborough Studio, London

Junius Spencer Morgan II, ca. 1900

Albumen print

Collection of Elisabeth Morgan

The Collection

J. Pierpont Morgan’s new Library was a treasury, not a place to curl up with a good book. In 1908, after a London Times journalist was offered a rare look inside, the New York Times printed this breathless front-page headline:

MR. MORGAN’S GREAT LIBRARY . . . One of the Chief Treasure Houses of the World. PARADISE OF THE BOOKMAN Bewildering Array of Noble Products of the Minds and Hands of Many Centuries. MORGAN CALLED A GENIUS “The Most Wonderful of All Collections by the Most Wonderful Collector, Perhaps, of Any Time.”

Hype and hyperbole aside, it was true that Morgan had gathered a “bewildering array” of bibliographic treasures and works of art. On view here are just a few of the medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts, rare printed books and bindings, literary and historical manuscripts, drawings, and prints the Times reporter saw during that early visit. Morgan had acquired them all (and much more) largely in the space of a decade. Morgan’s Library, the correspondent declared, was a place where “all the dreams of the bibliophile come true.”

Page from a Rajput manuscript of the Ragamala, created in India, probably Jaipur, ca. 1800. The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.211.

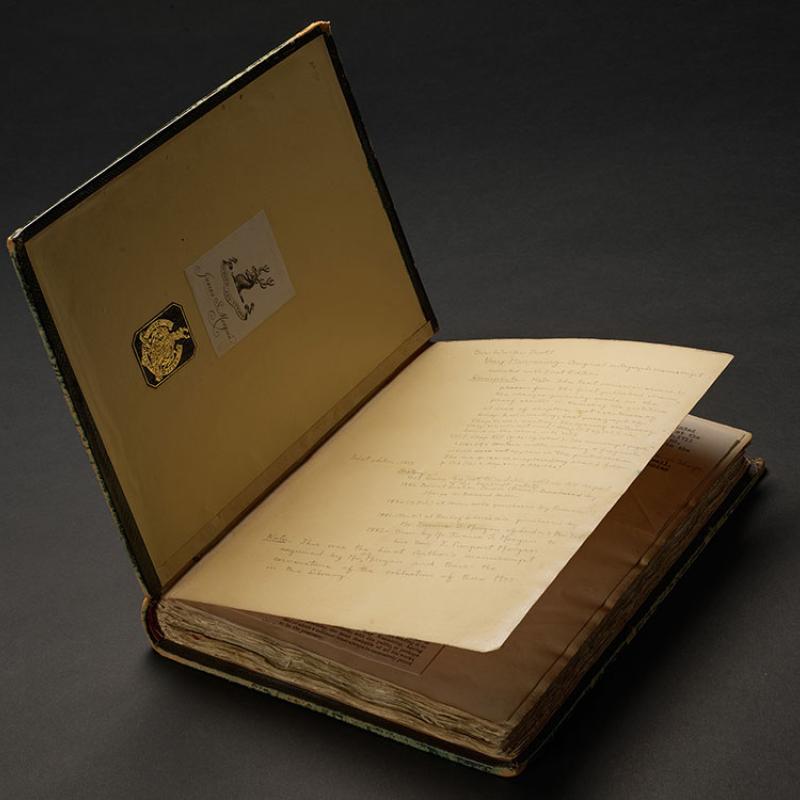

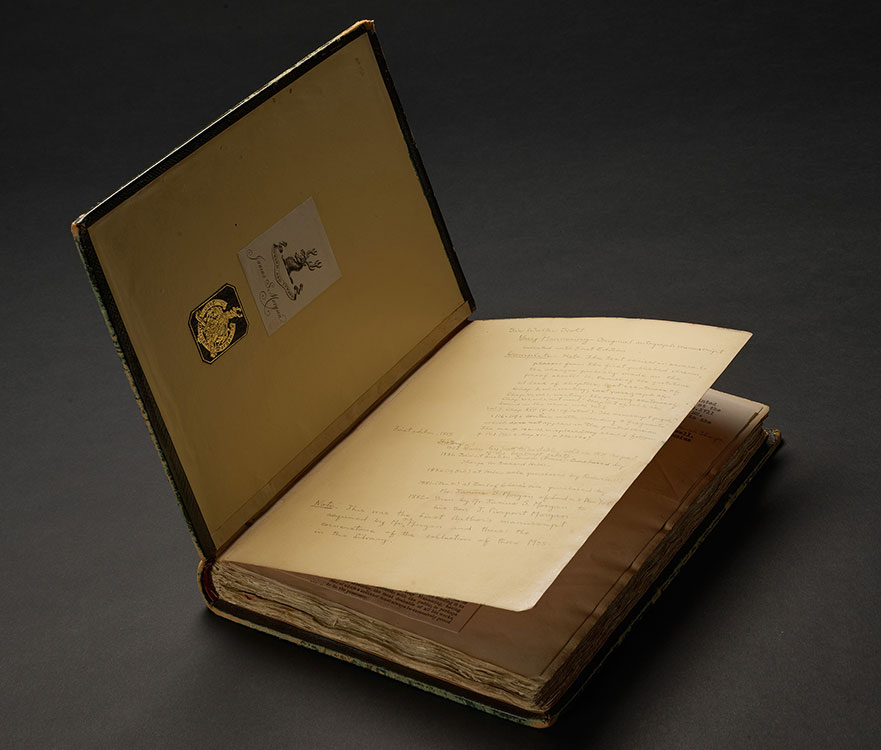

The "Cornerstone" of the Literary Manuscripts Collection

In 1881 Morgan’s father, Junius, learned that the manuscript of Sir Walter Scott’s second novel would be sold at auction. “If it’s genuine beyond the possibility of a doubt,” Junius told his agent, “I should like to own it.” Junius placed a successful bid of £390 and added his bookplate to this volume. Within a year, he presented the manuscript as a gift to his son, who placed his leather bookplate just below. Both feature the family motto, Onward and Upward. The extensive notes on the right were added years later by Belle da Costa Greene, the Morgan Library’s first director. At the foot of the page, she cited the item’s institutional significance.

Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832)

Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer

Autograph manuscript (one of three volumes), 1814–15

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by Junius S. Morgan, 1881, subsequently gifted to his son, J. Pierpont Morgan; MA 436–38

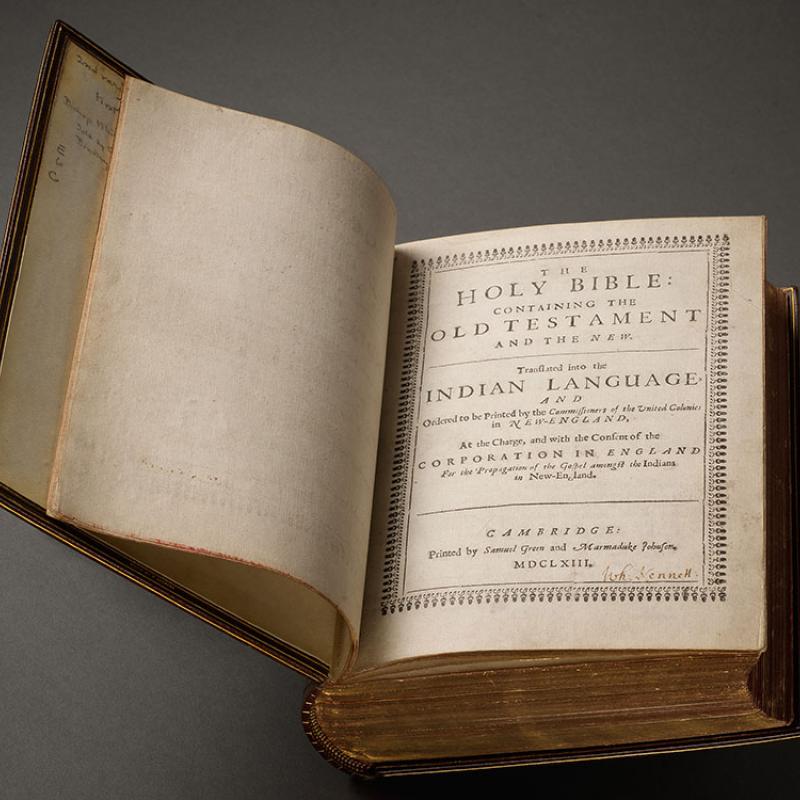

A 1663 Bible in the Wampanoag (Massachusett) Language

One of Morgan’s earliest notable purchases was both a landmark of American book history and an artifact of settler colonialism. The first complete Bible printed in the Western Hemisphere, the book was a project of the Reverend John Eliot (1604–1690), an English missionary of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This translation aligned with Eliot’s efforts to convert Native peoples to Christianity and divorce them from their traditional ways of life.

Morgan purchased this copy for $1,000 at the 1879 auction of Connecticut banker George Brinley’s library. The New York Times called it “the crowning wonder of the sale.”

Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God (The Holy Bible: Containing the Old Testament and the New)

Cambridge, MA: printed by Samuel Green and Marmaduke Johnson, 1663

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1879; PML 5441

Blake's Drawings for the Book of Job

The highlight of the 1902–3 rare-book auction season in England was a series of watercolors and proof engravings by the visionary English artist and poet William Blake. With Bernard Alfred Quaritch (son of the renowned London bookseller Bernard Quaritch) acting as his agent at Sotheby’s, Morgan purchased the collection for what the New York Times called the “sensational” sum of £5,712. One contemporary commentator noted the irony of the “phenomenally high prices” realized at the sale, given “Blake’s indifference to what the majority of us regard as the tangibilities of life.”

View the Morgan’s collection of Blake drawings

William Blake (1757–1827)

Job’s Sons and Daughter Overwhelmed by Satan, ca. 1805–10

Pen and black and gray ink, gray wash, and watercolor, over traces of graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1903; 2001.65</job’s>

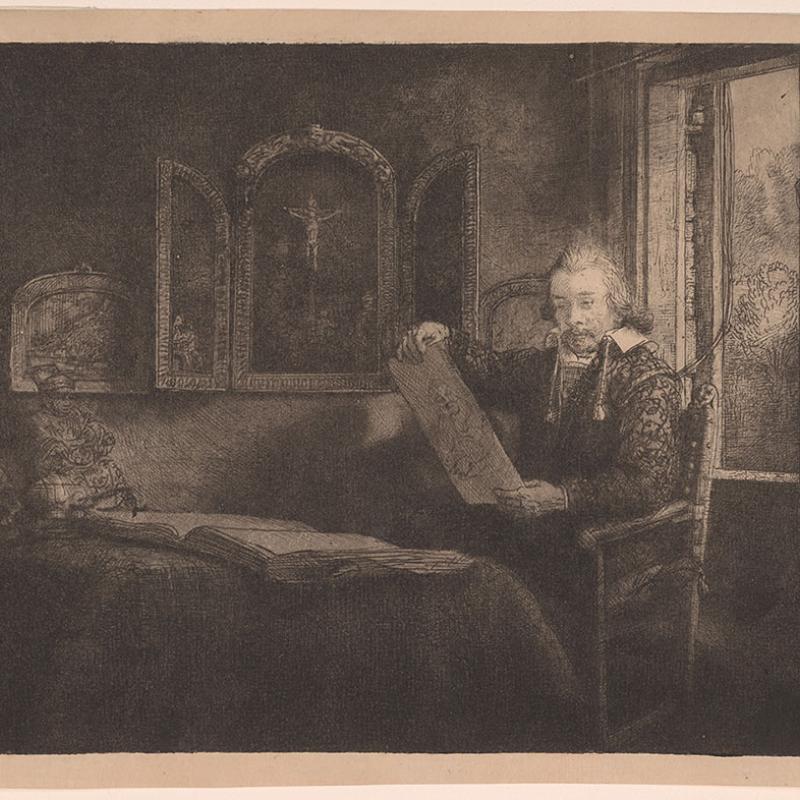

Rembrandt in the Library

This etching depicts an art collector in a moment of ease, a print or drawing in his hands and an open album on the table before him. Abraham Francen, the apothecary and connoisseur depicted, was apparently not a person of enormous means, but Rembrandt portrayed him in the company of rich and beautiful things—much like Morgan in his bookman’s paradise.

This is one of 112 prints by Rembrandt that Morgan purchased in 1905 from the collector George W. Vanderbilt, augmenting the 272 he had acquired with the library of Theodore Irwin in 1900. Morgan stored his print collection in custom cabinets in the top-floor “work room,” accessible to staff via elevator or a marble spiral staircase.

View the Morgan’s collection of Rembrandt etchings

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606–1669)

Abraham Francen, Apothecary, ca. 1657

Etching, engraving, and drypoint on Japanese paper

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1905; RvR 373

Women in the Bookman's Paradise

In 1896 Morgan acquired the manuscripts of two French novels by George Sand (one of which is shown here) and soon added manuscripts by the nineteenth-century English authors Anne and Charlotte Brontë. In 1893 Morgan passed on Lady Susan, the only surviving manuscript of a novel by Jane Austen. The Morgan Library eventually acquired it in 1947, long after Pierpont’s death.

While today most collectors prefer literary manuscripts to retain their original format, in Morgan’s day booksellers often had them sumptuously bound. This heavily gold-tooled leather binding by the London firm Riviere & Son is a typical example.

George Sand (1804–1876)

Les dames vertes

Autograph manuscript, ca. 1858, later bound in gold-tooled green morocco by Riviere & Son

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1896; MA 401

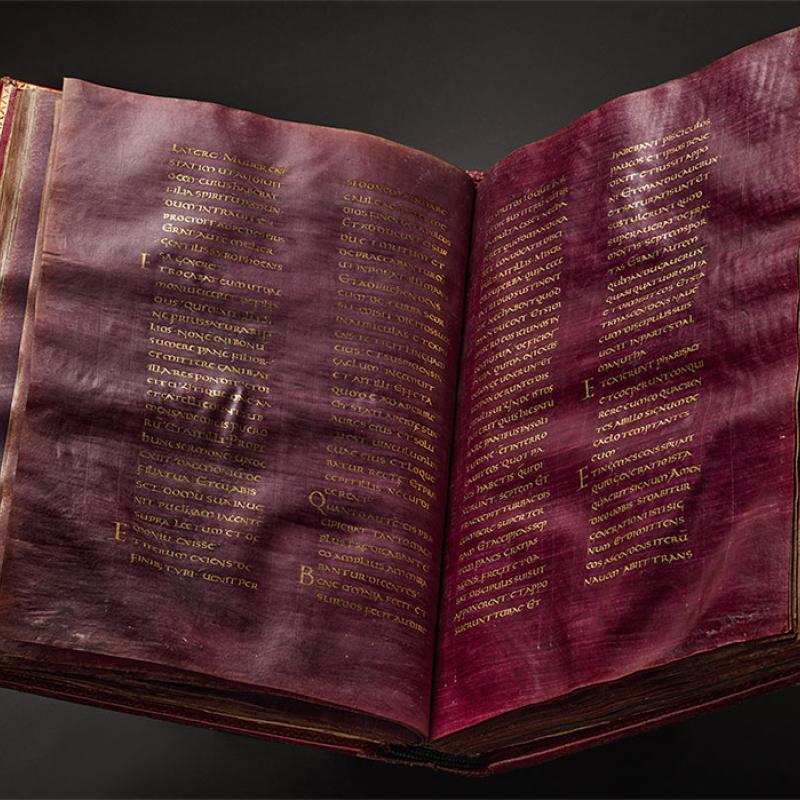

The Golden Gospels of Henry VIII

This thousand-year-old manuscript was created by about sixteen scribes in a Benedictine abbey in Trier (in what is now Germany). They used gold ink to copy the text of the Gospels onto parchment that had been dyed with a plant-based purple pigment, creating a luxury object that was likely an imperial gift. Though it was made in the tenth century, the manuscript has come to be known as the Golden Gospels of Henry VIII because the English monarch owned it some five centuries later. Morgan acquired it in 1900 as part of an en bloc purchase of more than three thousand books and manuscripts from the American manufacturer and financier Theodore Irwin.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Trier, ca. 980

Written and decorated in the Benedictine Abbey of St. Maximin

Purple parchment surface-dyed with orchil, gold letters

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.23

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan with the Irwin Collection, 1900

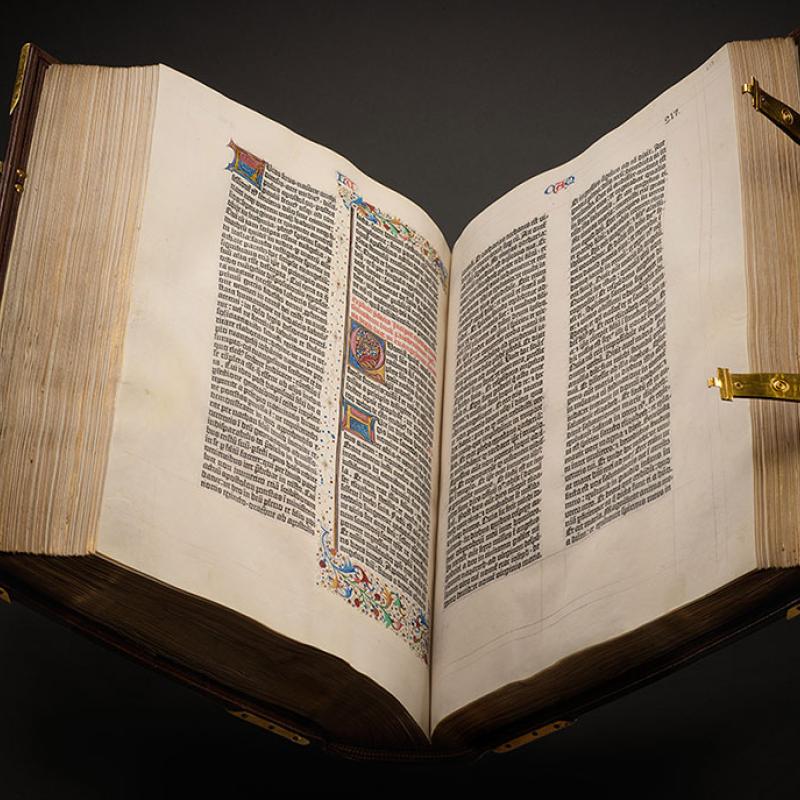

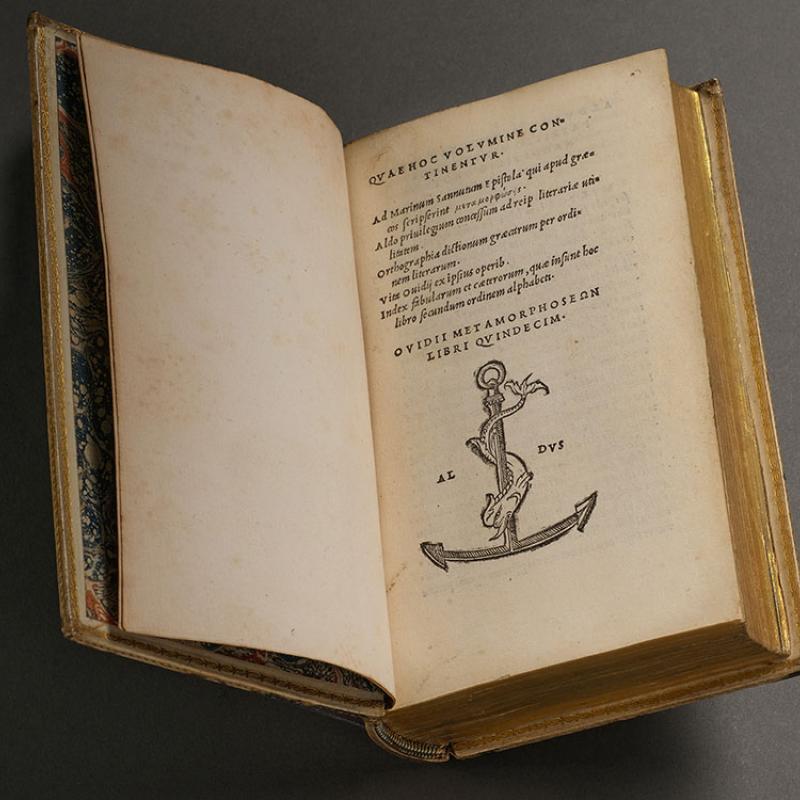

The Gutenberg Bible

There was a particular book that Morgan simply had to have as he began to direct significant resources to his library. He acquired this copy of the Gutenberg Bible in 1896 from the London firm Henry Sotheran & Co., paying £2,750. A landmark of printing history, it was the first substantive European book created with moveable type.

But one Gutenberg—even this desirable copy printed on vellum—would not prove sufficient. Morgan acquired two more, both printed on paper: a copy of the Old Testament (purchased with the Theodore Irwin collection in 1900) and a complete copy in two volumes (purchased in 1911 from the London dealer Bernard Quaritch).

View the Morgan’s Old Testament copy of the Gutenberg Bible

Biblia latina (Latin Bible)

Mainz: Johann Gutenberg and Johann Fust, ca. 1454–55

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1896; PML 818

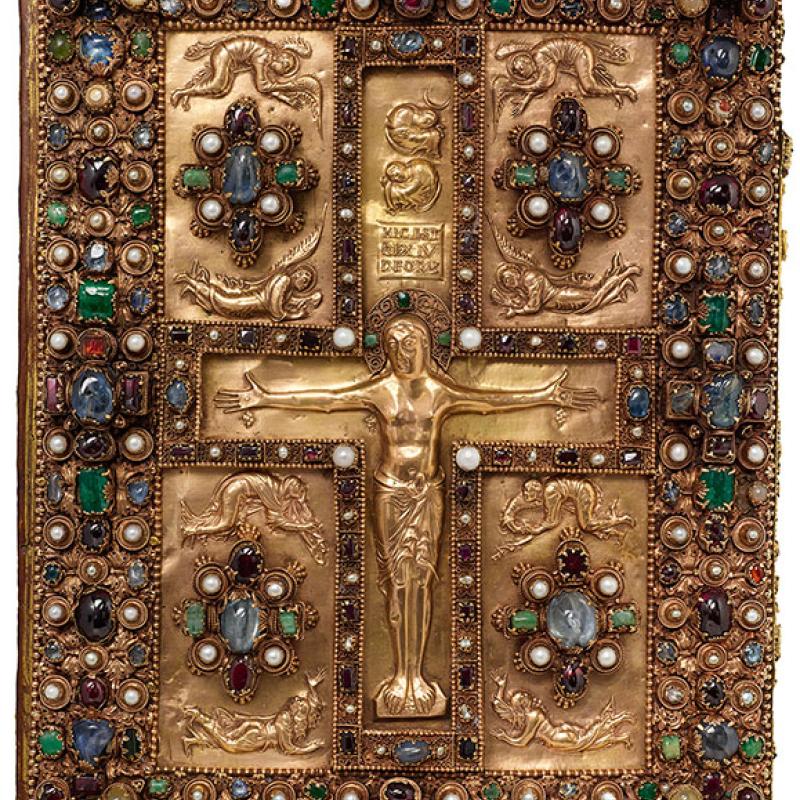

The Lindau Gospels

In 1899 Morgan received a telegram from his nephew Junius in London, alerting him to the availability of a “treasure of great value.” Writing in code, as was the Morgans’ custom when sending international wires, Junius offered tantalizing details about what would become the foundation of his uncle’s medieval manuscript collection: this ninth-century Gospel Book enclosed between jeweled metalwork covers. It came to be known as the Lindau Gospels because it was once housed in the Abbey of Lindau in Germany.

Morgan met the asking price of £10,000. The British government attempted, but failed, to raise the funds to keep this prize in the United Kingdom. By 1901 the volume was released to Morgan. When his new Library was completed five years later, he would have the volume installed alongside other dazzling bindings in a tabletop vitrine in the East Room.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Switzerland, St. Gall, ca. 880 (manuscript)

Eastern France, ca. 870 (front cover)

Austria, Salzburg region, ca. 780–800 (back cover)

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.1

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1901

Follower of Raphael

This painting was found by the artist and agent Charles Fairfax Murray and sold via a Roman gallery to J. Pierpont Morgan in 1910. After Morgan’s Library was completed, he sought this and other Italian Renaissance paintings to adorn the red-damask-covered walls of the West Room, his study.

The work was believed to be Raphael’s Holy Family (also known as the Madonna di Loreto), which had long been considered lost. Today, however, most scholars accept that the Musée Condé in Chantilly, France, has Raphael’s original and that this is one of numerous copies. The quality and refinement of the Morgan’s version suggest that it was executed by one of Raphael’s assistants during the master’s lifetime or shortly after his death in 1520. The Christ Child gazes at the Virgin and reaches toward her skillfully rendered veil—a reference to Christ’s shroud, or burial garment.

Follower of Raphael (Italian, early sixteenth century)

Holy Family, ca. 1515–20

Oil on canvas

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1910; AZ139

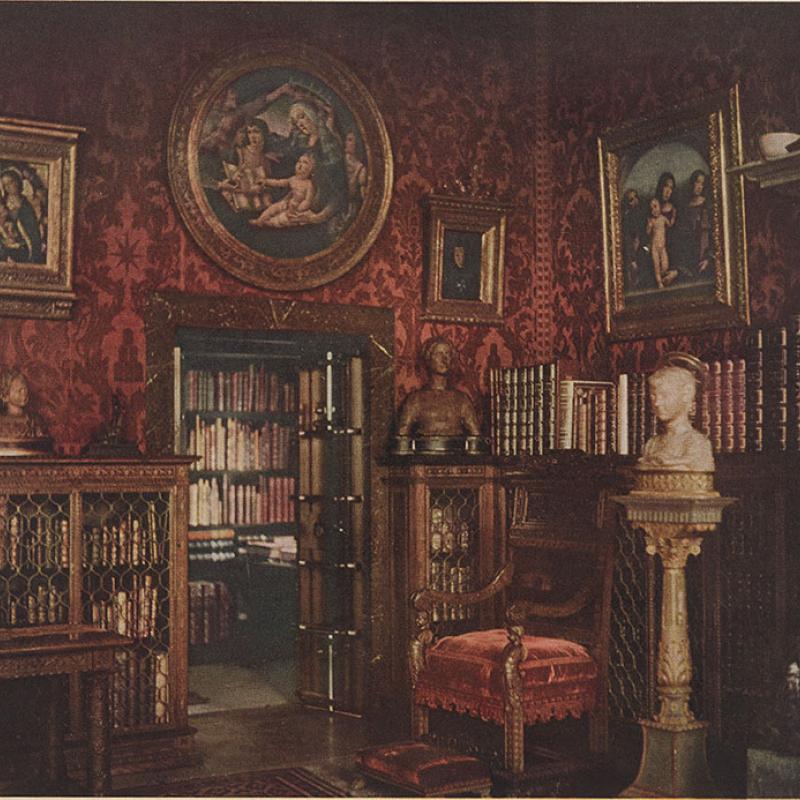

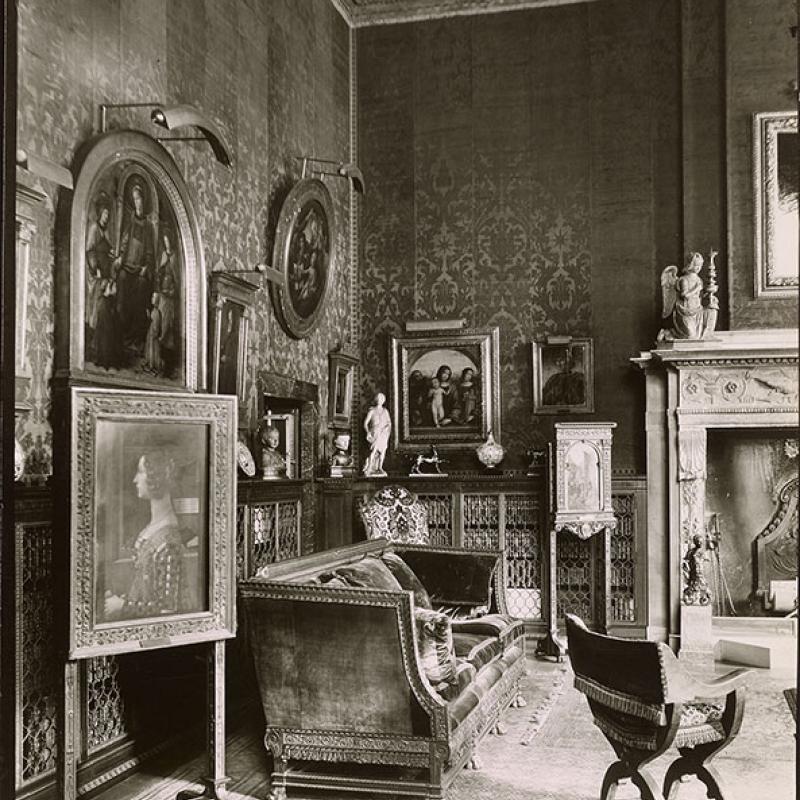

The West Room

“It is no impression of ostentation that one obtains upon entering,” wrote the London Times correspondent who visited the Library in 1908, “but one of exquisite, peaceful chambers in which a man superlatively fortunate may pass his hours divinely.” While ostentation (or lack thereof) may be in the eye of the beholder, J. Pierpont Morgan was certainly a fortunate man. He spent many hours here in his private study, smoking Cuban cigars, playing solitaire, and receiving guests.

Every available space was filled with splendid things: custom-made furniture in a sixteenth-century Italian style, small-scale artworks atop the low walnut bookcases, treasure bindings propped on tabletops, and oil paintings hung on the silk-covered walls or affixed to freestanding easels. A steel-lined vault housed medieval and Renaissance manuscripts as well as modern literary manuscripts and letters. The room itself combined antique elements with new, positioning its inhabitant as a latter-day Renaissance prince capable of acquiring, or commissioning, whatever he fancied.

Inside the Vault

Arnold Genthe was the first to photograph Morgan’s study in color, using a new technology invented by the French brothers Lumière. The completed glass plates, called autochromes, could be viewed with a hinged stand called a diascope, which incorporated a mirror that reflected the color image. Morgan was so pleased with Genthe’s work that he ordered multiple diascopes mounted into fine leather cases. Genthe later recalled the unusual circumstances of the shoot:

During the long exposure of the plates I was permitted to go into the vault where the rare and precious manuscripts were kept and to study those in which I was particularly interested. This of itself would have been ample compensation to me.

Arnold Genthe (1869–1942)

The West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1912

Color print, 1935, made from 1912 autochrome

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1586

An Art-Filled Study

Prominently displayed on the easel pictured here is one of several major works that Morgan purchased in 1907 (for a total of $2 million) from the estate of the German-born Parisian banker Rodolphe Kann. It is a fifteenth-century portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni by the Florentine artist Domenico Ghirlandaio. In the painting, depicted just behind the subject is a gilt-edged Renaissance-era prayer book much like those Morgan housed in the West Room’s vault.

Morgan’s son, Jack, sold the painting in the 1930s; it is now in the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. Three panels by the fifteenth-century Flemish master Hans Memling, which Morgan also acquired from the Kann estate, remain in the room today.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

The West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1612.1

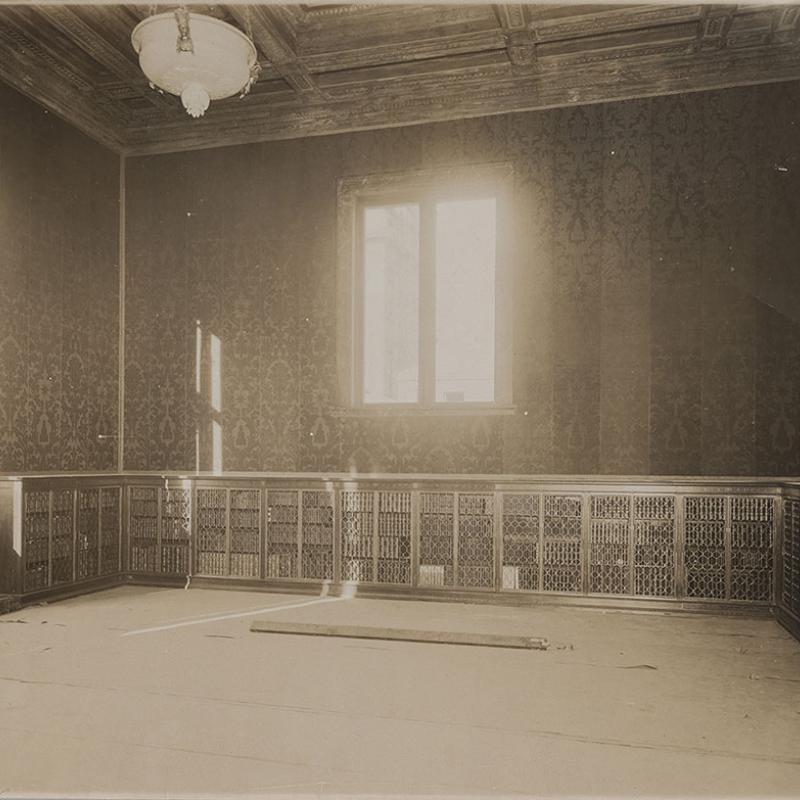

On the Eve of Move-in

During much of 1905 and into 1906, contractors and decorators scrambled to complete the interiors of Morgan’s Library. Here, the bookcases around the perimeter of his study have already been filled with gilt-lettered volumes. The shelves inside the steel-lined vault at right, however, remain empty, ready to receive Morgan’s collection of manuscripts.

The silk damask wall coverings incorporate images of an eight-point star and a pyramid-shaped cluster of six hills, elements of the heraldic arms of the Chigi family, powerful Sienese bankers of the Italian Renaissance. It is unclear how many of Morgan’s guests would have noted the reference.

Pach Brothers, New York

The West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library just after construction, ca. 1906

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1581

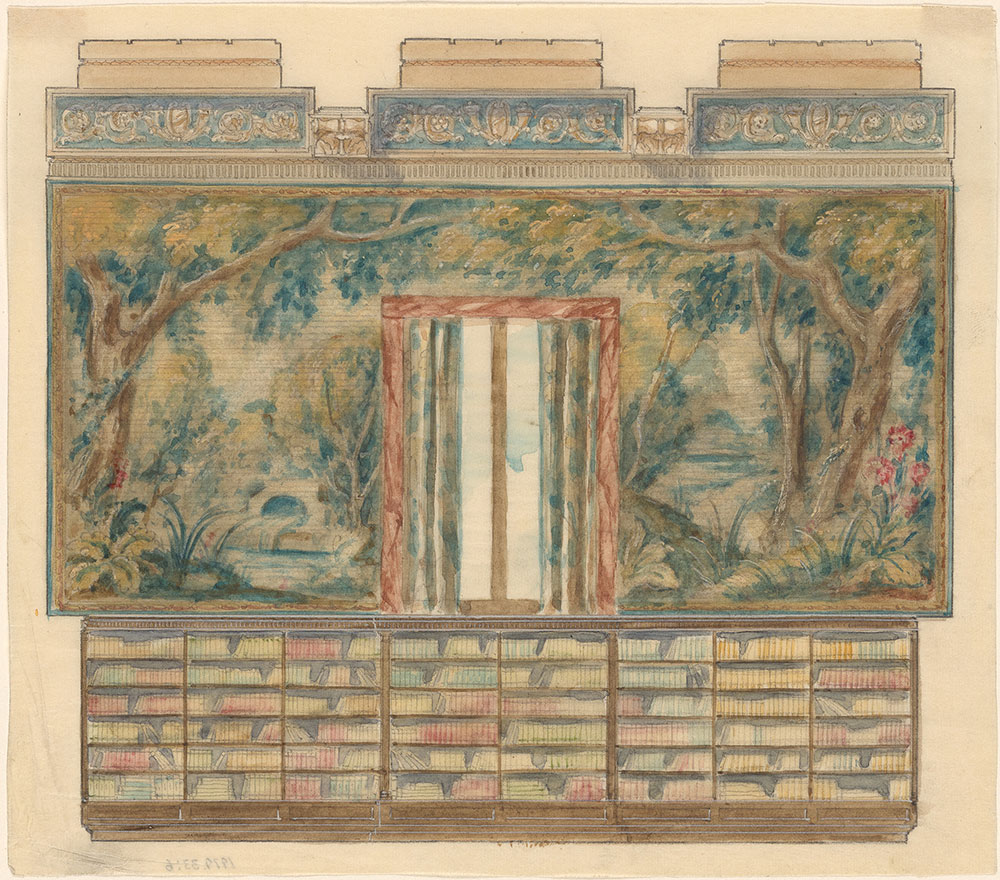

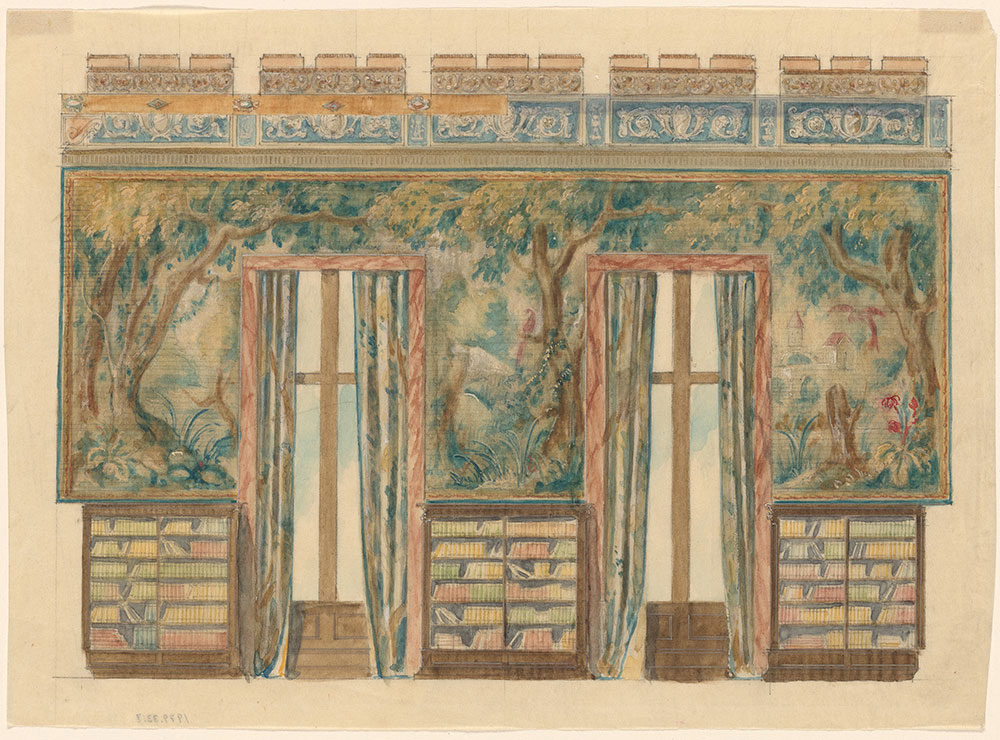

A Vision for Morgan's Study

McKim considered this verdant look for Morgan’s study during the early stages of interior design. But after viewing the art gallery in Lynnewood Hall, the Philadelphia-area mansion of industrialist Peter A. B. Widener, McKim shifted course. “You were kind enough to say last week,” McKim wrote to Widener, “that you would be glad to have Mr. Morgan avail himself of your experience in the selection of a material for the covering of the walls of one of the rooms in the library which we are building for him.” McKim secured fabric samples from Widener’s supplier and ultimately selected a crimson silk with a raised pile, which proved a more suitable backdrop for works of art.

For McKim, Mead & White (artist unknown)

Early designs for the West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1904

Graphite, watercolor, and tempera

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Mr. Walker O. Cain in honor of Charles Ryskamp on his 10th anniversary as Director; 1979.33:6–7

The Financier's Desk

The London decorator A. Barnard Cowtan told Morgan’s librarian, Belle da Costa Greene, that he had “well over one hundred men” working “nearly all night” to complete a large furniture order for the Library toward the end of 1906. For Morgan’s desk and other pieces, Cowtan’s designers drew inspiration from sixteenth-century Italian examples in the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A, London). Greene and assistant librarian Ada Thurston received custom-made desks and other bespoke office furniture as well.

The telephone may look out of place in a room that evokes Renaissance splendor, but it was very much a part of everyday business for both Morgan and Greene.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

The West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1619

"Woman Sewing the Velvet"

This six-page invoice, totaling £5,203, details the custom-made tables, desks, stools, table coverings, and other furniture pieces and adornments supplied by the venerable London firm Cowtan & Sons. Some pieces were shipped from London to be upholstered in New York, using 127 yards of antique velvet that Morgan had secured.

The last line item is a charge of £91 for the on-site work of the upholsterers, “including woman sewing the velvet.” This passing reference documents one of the very few women (albeit an unnamed one) who worked for a contractor inside the bookman’s paradise.

Cowtan & Sons, London

Statement of expenses issued to J. Pierpont Morgan, 1906

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Electric Light and a Burning Fire

This early view of Morgan’s study by the Austrian-born artist Emil Fuchs conveys a key characteristic of the room: its free juxtaposition of old and new. The mantelpiece is a composite of a fifteenth-century lintel and new components. The coffered wooden ceiling comprises new and antique elements as well as painted embellishments by the contemporary artist James Wall Finn. As a fire burns below, electric lights (including the hanging fixture with an alabaster shade) illuminate the room. While sixteenth-century majolica plates were placed atop the bookcases, the fireplace was crowned with a contemporary oil portrait depicting Morgan’s father, the banker Junius Spencer Morgan.

Emil Fuchs (1866–1929)

The West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1907–8

Oil on panel

The Morgan Library & Museum, transfer from the Brooklyn Museum, 2018; AZ204

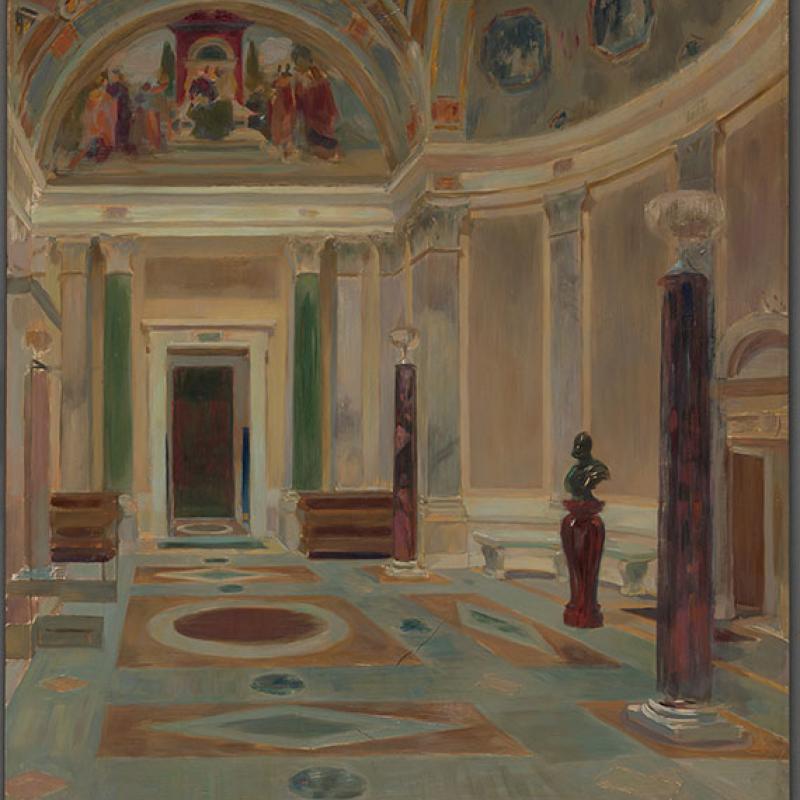

The Rotunda

J. Pierpont Morgan’s guests must have been surprised as they passed through his Library’s front doors and stepped into what the architects called the main hall. In a New York minute, they had left an ordinary urban sidewalk and entered a soaring space full of color and ornament. It was impossible not to gaze upward: the ceilings were decorated with painted murals and stucco reliefs, heightened with gold.

To create this “lofty hall of rarest marble,” as the London Times called it in 1908, architect Charles Follen McKim incorporated strong echoes of luxurious spaces built in Rome in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. But the freestanding marble columns in the Rotunda of Morgan’s Library were wired for electric light—a reminder that the building was a twentieth-century creation, not an Italian Renaissance palace.

The Rotunda at "the Witching Hour"

Around 1907 Morgan apparently consented to pose for the Austrian-born artist Emil Fuchs, a successful portrait painter working in London and New York. In his autobiography, Fuchs explained that he declined to proceed with the portrait because “the gulf between [Morgan] and the mere outside world was immeasurable” and “I should not have been able to approach close enough to penetrate behind that concealing mask.” For Fuchs, however, the encounter led to a welcome opportunity:

His librarian obtained permission for me to sketch the interior of his treasure-house at night. This was a task to my liking. To be surrounded by the art of bygone days in the witching hour of the night, gave me far more pleasure than the dinner parties I thus missed.

Emil Fuchs (1866–1929)

The Rotunda of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1907–8

Oil on panel

The Morgan Library & Museum, transfer from the Brooklyn Museum, 2018; AZ203

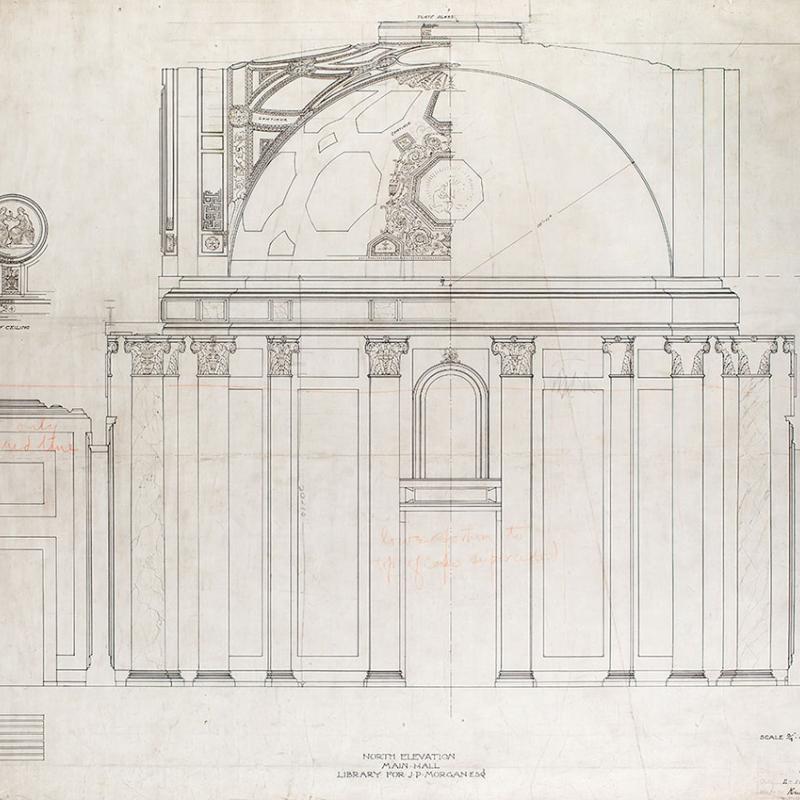

Designing the Rotunda

In early 1904, two years after Morgan had commissioned the Library, McKim and his partner William Rutherford Mead were finally ready to present the interior designs. “The proposition we desire to submit for your consideration,” McKim wrote to his client, “is the result of months of study, & I trust in its general policy will commend itself as dignified and appropriate to the purposes of a library.”

William Mitchell Kendall, one of the architects working on the project with McKim, created this elevation of the Rotunda, or “main hall.” He began to articulate the decorative details that would ultimately distinguish the completed space.

William Mitchell Kendall (1856–1941) for McKim, Mead & White North Elevation, Main Hall, Library for J. P. Morgan Esq., 11 February 1904 Ink on linen New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

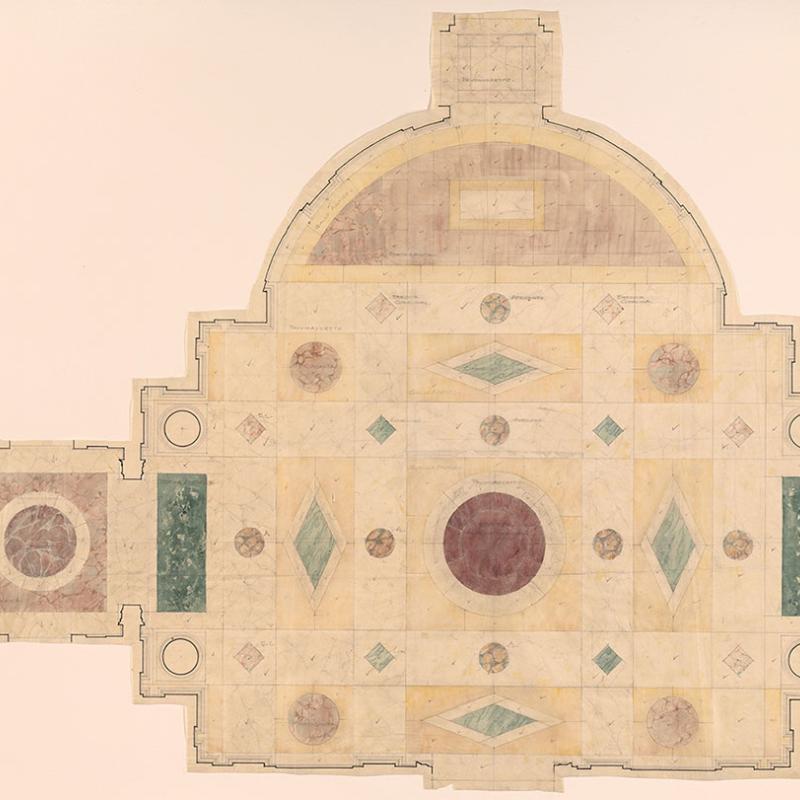

The Rotunda's Marble Floor

While McKim designed the Library with the aim to draw the eye upward, he was equally attentive to the ground below. This is one of several surviving drawings that record the firm’s careful planning for the pavement of the Rotunda, which pays homage to the sixteenth-century Casina Pio IV (Villa Pia) in the Vatican Gardens. McKim asked the sculptor Waldo Story, who was living in Rome, to scout antique marble samples of a variety of hues, with a particular focus on securing the central disc of deep-red-purple porphyry.

For McKim, Mead & White (artist unknown)

Design for the pavement of the Rotunda of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1904

Watercolor

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1979.33:1

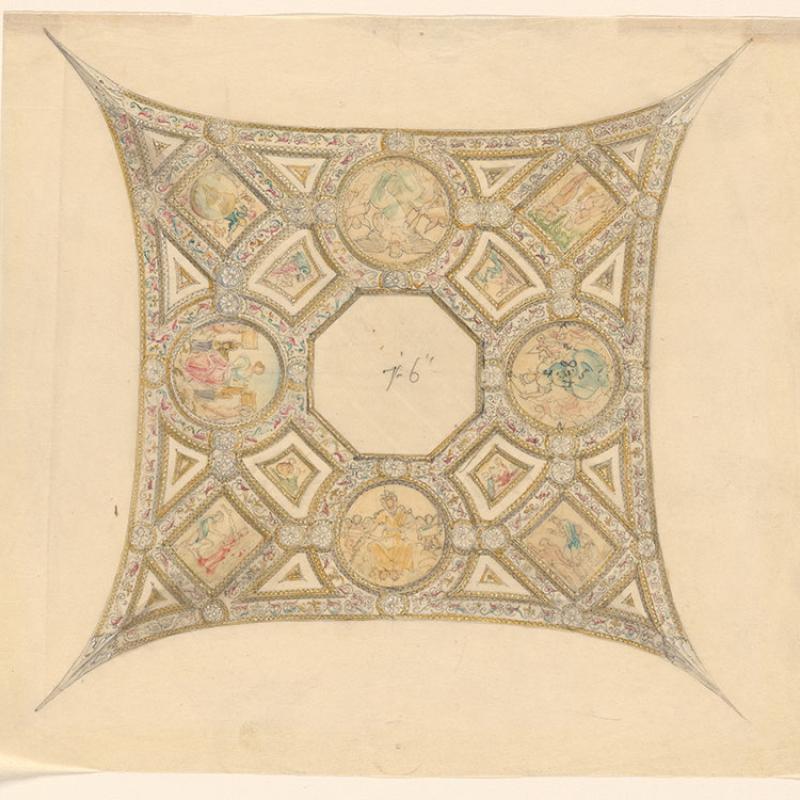

Detailing the Dome

William J. Sayward was one of the architectural drafters at McKim, Mead & White assigned to work closely with contractors on the Morgan Library project. He created this intricate drawing for the ornamentation of the Rotunda’s dome, which would incorporate a central skylight, or oculus (here marked “plate glass”). The artist H. Siddons Mowbray, who was engaged to create the painted decoration, would refine these designs for the roundels and other paintings, taking into account that “the ceiling is pierced by light.”

William J. Sayward (1875–1945) for McKim, Mead & White

Detail of Ceiling, Main Hall, Library for J. P. Morgan, Esq., 10 February 1904

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

The Apse in Color

This watercolor rendering complements the more technical elevation of the proposed design for the Rotunda seen nearby. The color scheme for the semicircular dome of the apse would ultimately be simplified to a solid white with blue and gold accents. Like many elements of the Library, it was adapted from a sixteenth-century Roman source, in this instance the garden loggia of the Villa Madama.

The artist H. Siddons Mowbray was engaged to create the reliefs, which depict Roman mythological figures and allegorical representations of nature. Mowbray completed the modeling on-site, climbing up and down the scaffolding many times to ensure that his creations would be effectively illuminated by the Rotunda’s skylight.

For McKim, Mead & White (artist unknown)

Design for the Rotunda of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1904

Watercolor

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1979.33:2

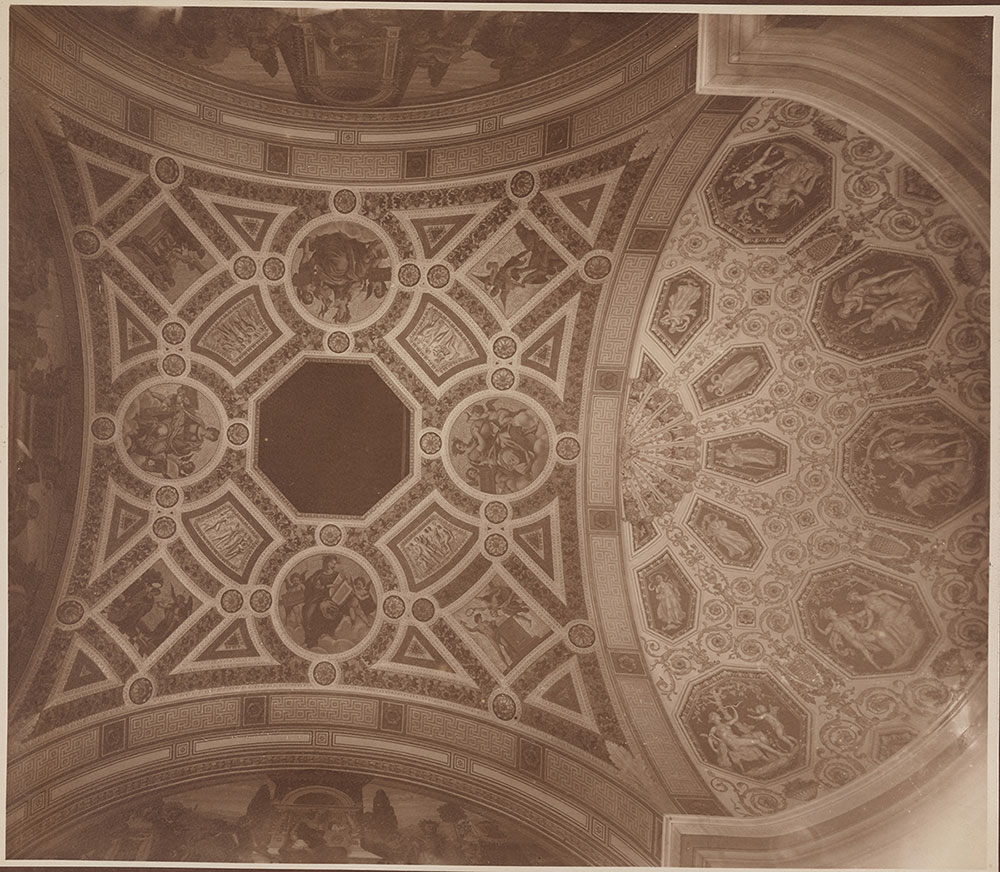

Drawing on Raphael

As they developed this design for the dome of the Rotunda, McKim, Mead & White turned to the ceiling frescoes Raphael had created for the Vatican’s Stanza della Segnatura in the early sixteenth century. It was an appropriate (if grandiose) choice: Pope Julius II had used the room as a library and private office.

As they developed this design for the dome of the Rotunda, McKim, Mead & White turned to the ceiling frescoes Raphael had created for the Vatican’s Stanza della Segnatura in the early sixteenth century. It was an appropriate (if grandiose) choice: Pope Julius II had used the room as a library and private office.

For McKim, Mead & White (artist unknown)

Preliminary design for the dome of the Rotunda of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1904

Watercolor

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1979.33:4

Mowbray at Work

In 1904 McKim engaged the American artist H. Siddons Mowbray to execute the twelve paintings that would be inserted into the Rotunda ceiling. “It will necessitate a period of study in Rome, of examples of decoration of the same period,” Mowbray told McKim.

Mowbray made this copy of a portion of Raphael’s frescoed ceiling in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican, making some adjustments to the colors of the borders. For the four roundels in the dome of the Rotunda of Morgan’s Library, Mowbray would adapt Raphael’s work and portray female personifications of the humanist ideals of art, science, philosophy, and religion.

H. Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928)

Copy after Raphael’s vault of the Stanza della Segnatura, 1904 or 1905

Watercolor and opaque watercolor, with gold, over graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Hugh Jones; 1989.20

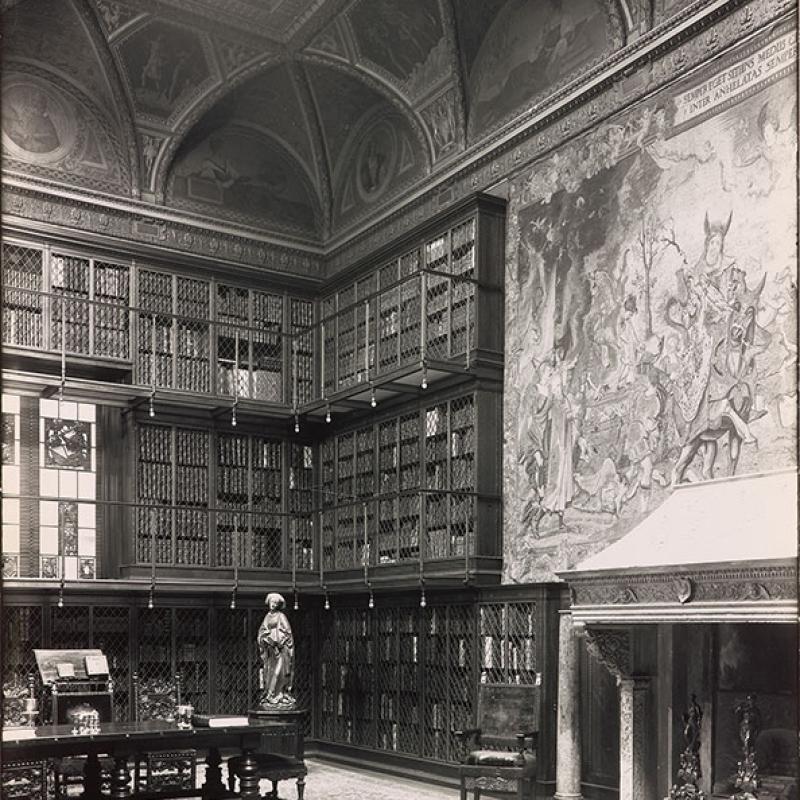

The East Room

J. Pierpont Morgan left no written record of how he wanted his library-within- the- Library to look or the cultural values he wished it to convey. But we know he was satisfied with the showplace Charles Follen McKim delivered. The completed East Room is an American homage to European creativity and a conspicuous display of wealth. To the London Times correspondent who visited in 1908, it was paradise. “Here, at last,” they wrote, “is the ideal library, the ideal setting for noble books.”

A sixteenth-century tapestry serves as the focal point of the room. Several of the bookcases swing open to reveal hidden staircases that provide access to the second and third tiers of shelves. Above it all is an extravagant ceiling. But surrounded as they are by this profusion of ornament, it is the books—some fourteen thousand of them—that define the room.

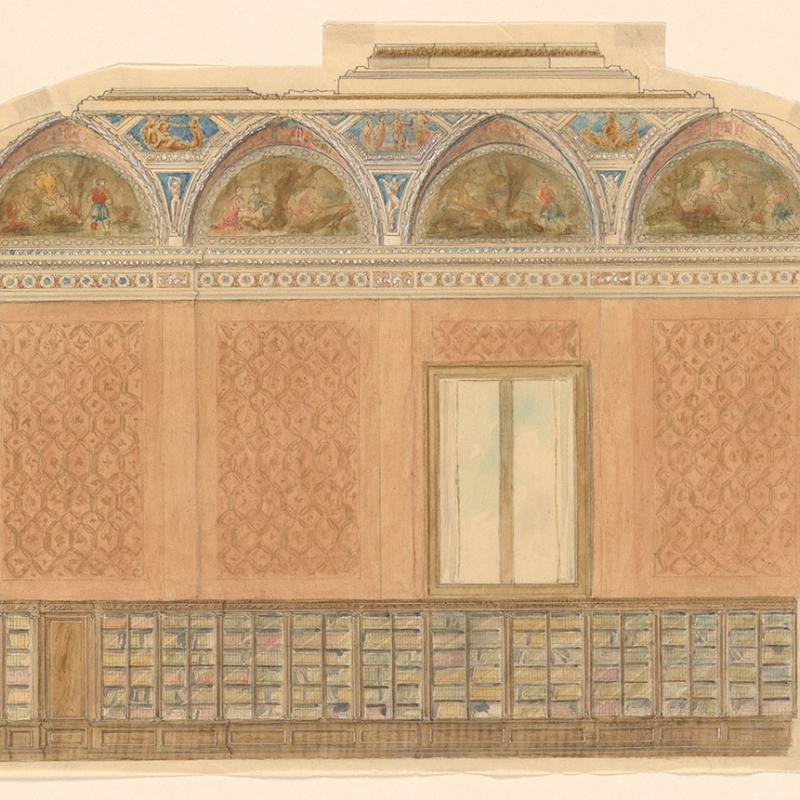

Envisioning a Library

This rendering of McKim, Mead & White’s early vision for one of the East Room walls bears only a hint of resemblance to the finished space. While the coved ceiling with its series of painted lunettes and spandrels would remain, the scenes depicted here would be replaced with murals of an entirely different design. There would be no patterned red wall coverings. Instead of a single continuous bookcase ringing the room, there would be three, one atop the other, creating a wall of books.

For McKim, Mead & White (artist unknown)

Preliminary design for the East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1904

Watercolor

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1979.33:10

The Approved Design

Morgan approved this plan for the East Room of his Library in 1904, and the room was constructed as depicted, though major changes would be introduced in the final stages.

Here, the lunettes are all marked “painting,” to note where ceiling murals by the artist H. Siddons Mowbray would be installed. At top left, the words “Guastavino construction” indicate that the vaulted ceiling would be erected by the firm established by Rafael Guastavino, an immigrant from Spain known for his innovative tiling method. The Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini would supply the stone mantelpiece, though the ornamental top would later be lopped off to make way for a sixteenth-century tapestry.

August Reuling (1884–1966) for McKim, Mead & White

Section through East Room Looking East, Library for J. P. Morgan Esq., 3 June 1904

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Under Construction

It is astonishing that construction proceeded this far before it became clear that the East Room would not come close to accommodating Morgan’s vast collection of rare books. The shelving contractor, anticipating this outcome, had reinforced the Circassian-walnut bookcases “with tee irons sufficiently strong to carry two stories above when the growth of the library has made such expansion necessary.” That moment arrived in 1906, just as McKim thought the building was nearing completion.

The Library was thrust back into construction mode. The windows depicted here were covered with new bookcases, and the corresponding openings in the faultless exterior were filled in with additional marble blocks.

Pach Brothers, New York

The East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library under construction, ca. 1906

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1578

The Completed Library

Cabinetmakers and builders added two tiers of bookcases during the final stages of construction. Instead of a grand room that happened to house books, the East Room of Morgan’s Library was thus transformed into a space whose function was unmistakable. Long study tables and lecterns were custom-made for the room. In 1911 (after McKim had died), Morgan acquired the sixteenth-century German sculpture of a saint, possibly Elizabeth of Schönau. She is depicted—appropriately—with book in hand.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

The East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Photograph

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1601.1

Mowbray's Reclining Women

Though women were depicted prolifically inside the bookman’s paradise, they appeared most often as allegorical, rather than historical, figures. In nine of the East Room’s ceiling lunettes, Mowbray painted lounging female figures representing tragedy, comedy, painting, architecture, poetry, history, music, science, and astronomy. He took inspiration from the four sibyls (women prophets) portrayed by Pinturicchio in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome. Mowbray told the architects that his color scheme would evoke “the softened harmony and patina of an old room,” with gold accents conveying “the tonal quality of an old Florentine frame.”

H. Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928)

Study for the figure of Music in the ceiling of the East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1904 or 1905

Graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Mrs. Harry S. Mowbray; 1981.75:2

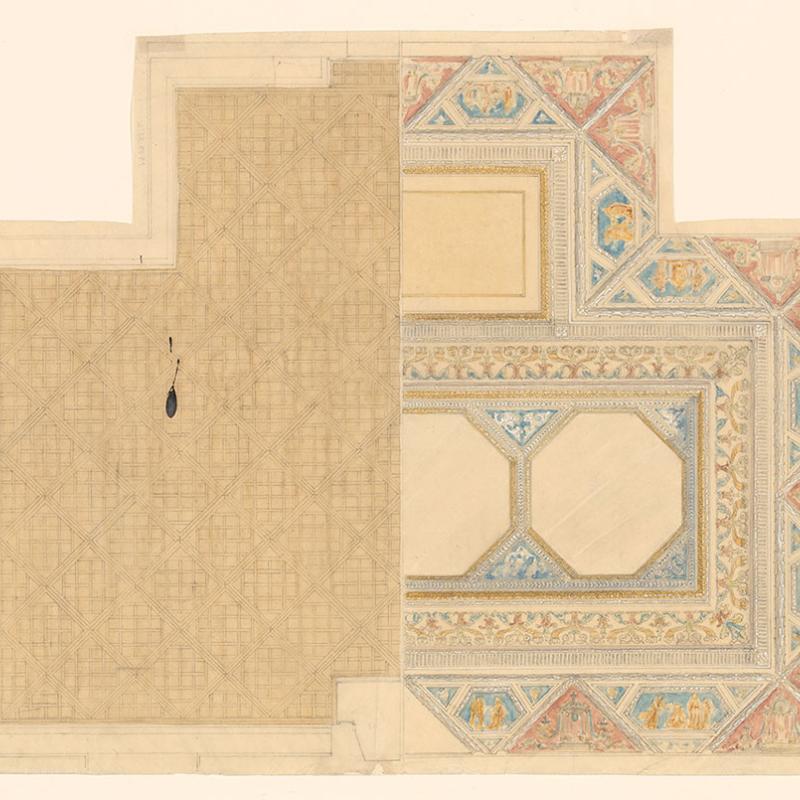

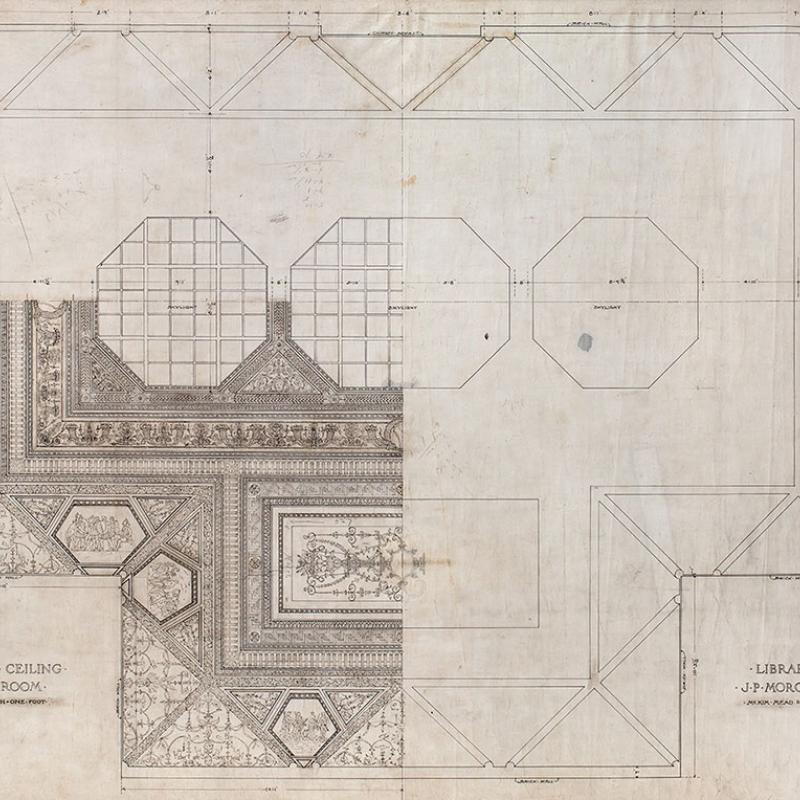

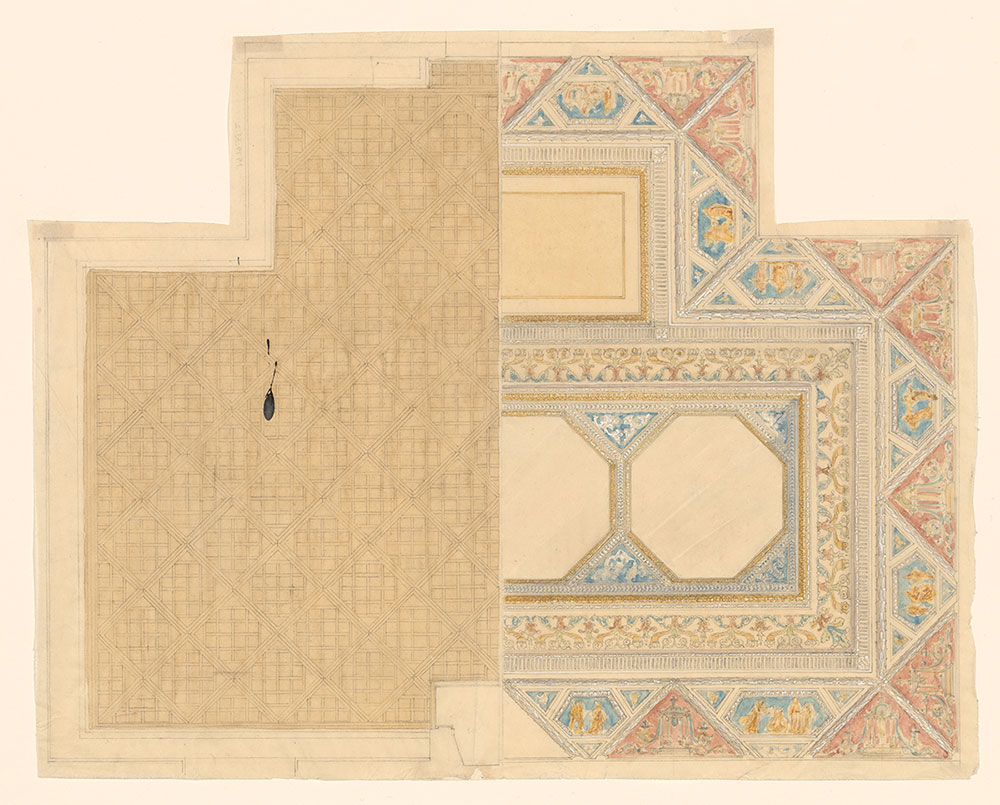

Ceiling and Floor

The left half of this drawing is an early outline for the East Room’s ornate ceiling; the right side depicts the design for the space’s parquet floor. While the color scheme and decorative details would evolve, this ambitious plan for the ceiling was carried out. The floor, too, was laid essentially as shown—replicating the oak parquet that had recently been installed during McKim, Mead & White’s renovation of the White House.

For McKim, Mead & White (artist unknown)

Design for the floor and ceiling of the East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1904

Watercolor

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1979.33:3

Presidential Parquet

McKim, Mead & White’s 1902 renovation of the White House included G. W. Koch & Son’s oak parquet floors, which President Theodore Roosevelt's children found to be a convenient surface for roller-skating. Here, the same contractor placed a bid to lay floors in Morgan’s Library in precisely the same style. He later submitted a revised, successful bid of $2,700, along with this explanation:

We have not figured this work to see how cheaply we could do it, but have made out prices so that we can afford to do this work in the very best manner possible, both as to workmanship, and material, as we presume that Mr. Morgan will appreciate quality more than he will price.

G. W. Koch & Son

Bid for flooring for J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 18 February 1904

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

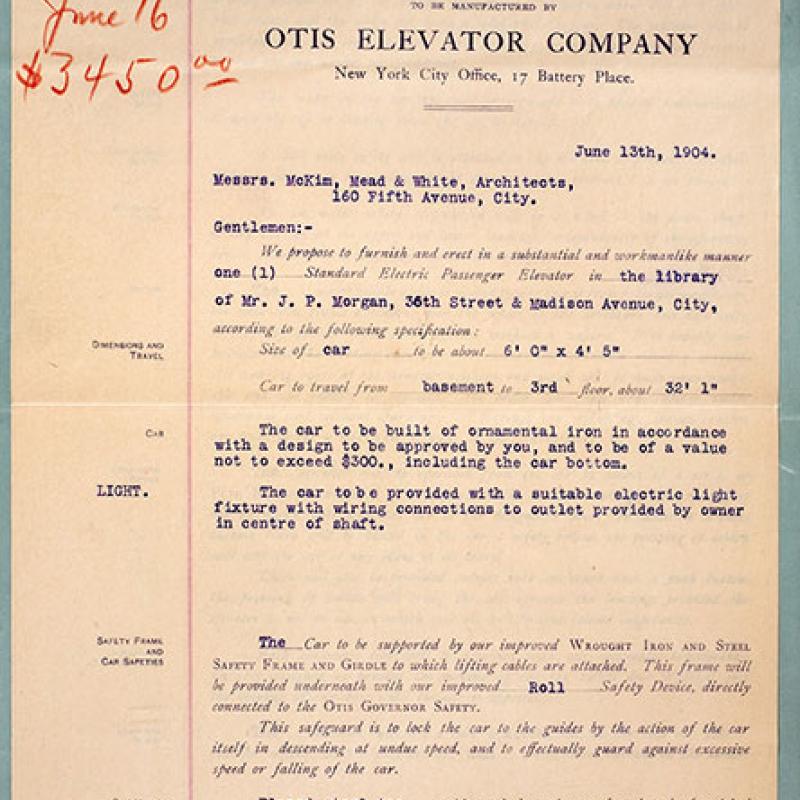

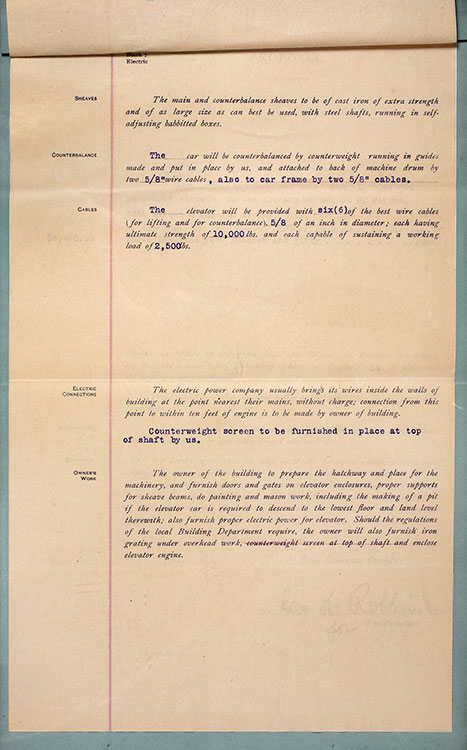

An Otis Elevator

While McKim designed Morgan’s Library in an Italian Renaissance style and adapted ancient Greek construction techniques, the building was very much a contemporary creation. The Otis Elevator Company installed an electric engine in the cellar and created an elegant passenger car to the architects’ specifications. Electrical fixtures were added to the car by the firm Edward F. Caldwell & Co. More than a century later, the elevator is still used by staff.

Otis Elevator Company

Specifications for Standard Electric Passenger Elevator for J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 13 June 1904

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

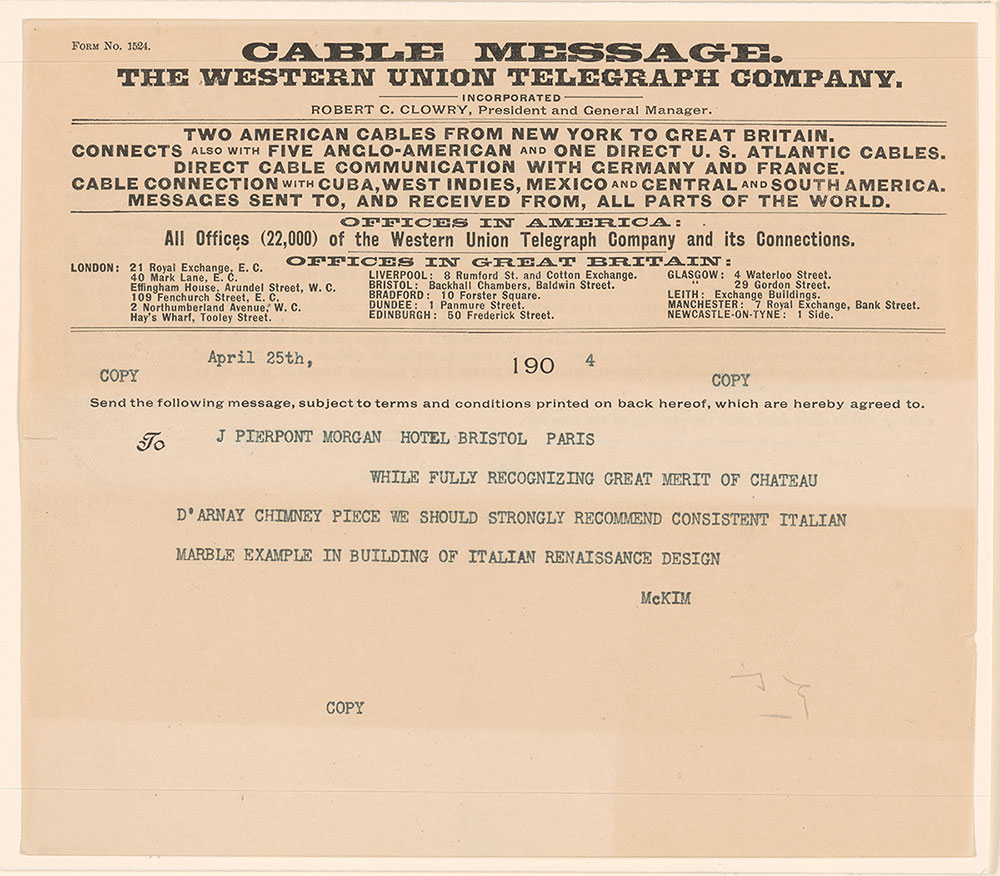

Architect and Client

While traveling in Europe and meeting with dealers in 1904, Morgan learned of the availability of a sixteenth-century French mantelpiece he had seen illustrated in Claude Sauvageot’s book Palaces, Castles and Residences in France. He wired McKim to alert him. In this response, the architect was deferential but firm: this French component had no place in a building “of Italian Renaissance design.”

McKim prevailed. All the mantels ultimately installed in the Library would be Italian antiques. New York tradespeople initially refused to set them because the stone had not been cut by union laborers, but the matter was resolved.

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909)

Telegram to J. Pierpont Morgan, 21 November 1904

Morgan Library & Museum Archives

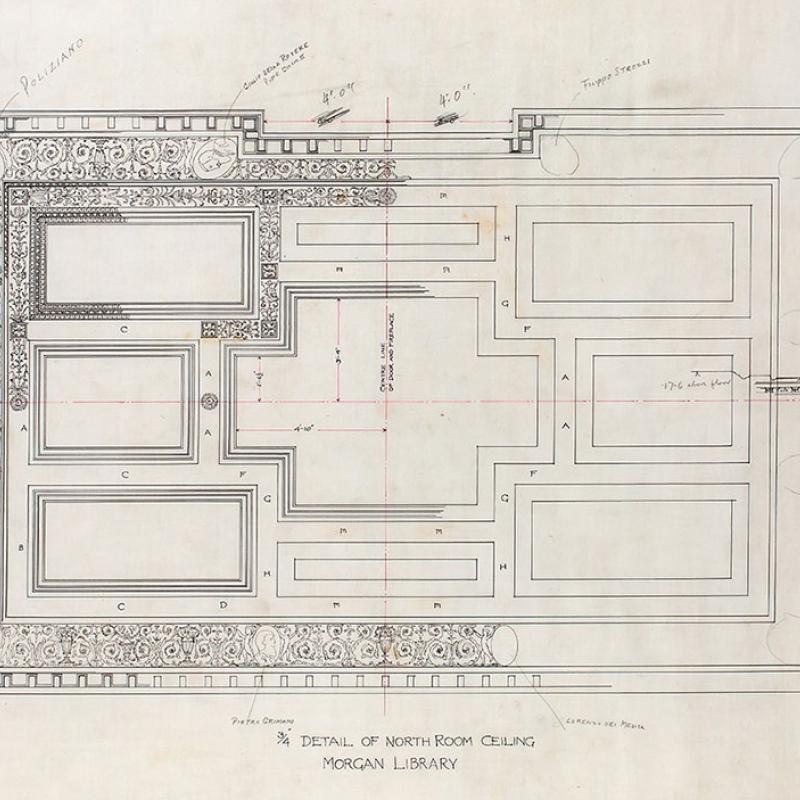

Designing the East Room Ceiling

August Reuling, a drafter for McKim, Mead & White, created the meticulous drawing that would guide the builders and artisans who would model, paint, and gild the extensive ornamental detail in the East Room ceiling. The three octagonal shapes represent the three laylights (large, flat pieces of semitransparent leaded glass) that would illuminate the room.

August Reuling (1884–1966) for McKim, Mead & White

Plan of Ceiling, East Room, Library for J. P. Morgan Esq., 19 May 1904

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Poetry Through the Ages

As he developed designs for the three lunettes (the semicircular paintings over the principal doors) in the Rotunda, Mowbray consulted a volume that reproduced Pinturicchio’s fifteenth-century decoration of the Borgia Apartments in the Vatican. Taking the Italian painter’s work as a point of departure, Mowbray populated the Morgan lunettes with familiar figures from ancient, medieval, and Renaissance poetry. In the mural over the Library’s front doors, the central altar is flanked by King Arthur (at left, with his lance and the Holy Grail) and Beatrice (Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s beloved, at right). The trompe-l’oeil archway above provides the illusion of depth.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

South lunette in the Rotunda of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1782

Mowbray's Ceiling Murals

In a series of lunettes (paintings in the shape of a half-circle) for the East Room ceiling, the artist H. Siddons Mowbray alternated depictions of nameless women with portraits of specific historical men, each representing a field of knowledge or creativity. Here, the female figure personifying music appears next to a portrait of the ancient Greek historian Herodotus.

Mowbray was one of the most generously paid contributors to Morgan’s Library. For his work on the East Room and Rotunda ceilings, Mowbray earned $46,406. The architectural firm McKim, Mead & White earned a total commission of $59,700 (5 percent of building costs, plus 10 percent of special costs); Charles T. Wills, the project’s general contractor, was paid $30,000.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

Ceiling murals in the East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1777

The Builders

The stoneworkers pictured here are among the hundreds of people, their names largely unknown to us today, who built the bookman’s paradise. They were photographed in a Bronx shop full of intricately carved marble blocks destined for the loggia of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library. Charles Follen McKim, the lead architect and creative force behind the Library, relied on a team of proficient drafters in McKim, Mead & White’s studio to create the drawings that articulated his vision. He engaged Charles T. Wills as general contractor and a host of specialists to build and ornament the Library. Just after construction began in 1903, a series of strikes brought the entire New York building industry to a standstill. Progress on the Library was delayed as workers sought improved conditions and better pay.

Stone carvers in the shop of Robert C. Fisher & Co., late 1904 or 1905. Museum of the City of New York, 90.44.1.675

An Italian Renaissance Precedent

As McKim developed his plans for the Library’s façade (and, later, the interiors), he made ample reference to Italian buildings designed for the political and financial elites of the Renaissance. He thus positioned Morgan as their American heir. The entry to the sixteenth-century Villa Medici, designed largely by Bartolommeo Ammannati, was a notable architectural source.

James Anderson (1813–1877)

The Villa Medici, Rome, 1865

Albumen print

Collection of W. Bruce and Delaney H. Lundberg

The Building Blocks of Morgan's Library

The first exterior elevations of the Library were created in March 1903 by a drafter who signed “Stevens”—likely Gorham P. Stevens, who worked for McKim, Mead & White before departing to serve as the inaugural architectural fellow at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens. Once construction of the Library was underway, McKim would send Stevens several squeezes (molds) of the spaces between the marble blocks, telling him, “Our vertical joints are nearly, if not quite, as good as the best of the Greek, it being impossible to insert a knife blade between them.”

Note the maned lion depicted at the Library’s entrance. The sculptor Edward Clark Potter would ultimately produce lionessses instead.

Probably Gorham P. Stevens (1876–1963) for McKim, Mead & White

East Elevation, Library Building for J. P. Morgan, Esq., 3 March 1903

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

McKim and the American Academy in Rome

In 1901 McKim sought Morgan’s endorsement for a cherished project: a new academy in Rome that would serve as a classical training ground for American artists and architects. Morgan agreed to join fellow collector and businessman Henry Walters in a public declaration of support. A few months later, in early 1902, Morgan invited McKim to his home for breakfast and asked him to design his Library.

Morgan ultimately joined Walters in providing significant financial support for the American Academy in Rome, which would become a major international center for scholarship and creative exchange. It still thrives today.

W. Kurtz, New York

Charles Follen McKim, ca. 1880s

Cabinet photograph

Avery Classics Collection, Columbia University

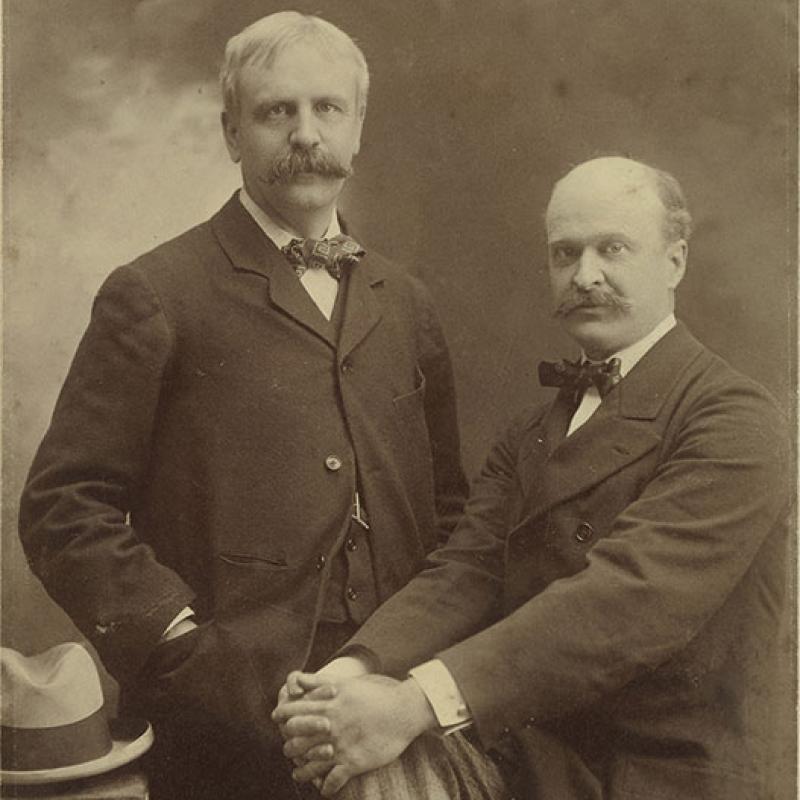

McKim to Mead: "The Office [is] Prospering"

“I think you will agree [that] the office [is] prospering, when I tell you of the several new jobs in hand, as well as in prospect,” McKim wrote to his business partner William Rutherford Mead in April 1902. One architectural commission McKim, Mead & White had just secured was New York’s monumental new Pennsylvania Station, which would open in 1910. Another, McKim explained, was from Morgan, who wanted to “build a little Museum building to house his books and collections.”

C. L. Howe & Son, Brattleboro, Vermont

William Rutherford Mead and Charles Follen McKim, ca. 1890s

Cabinet photograph

Avery Classics Collection, Columbia University

What Morgan Wants . . . (1)

In the early stages of the design process, J. Pierpont Morgan’s son-in-law Herbert Satterlee took the lead in communicating with McKim, passing on information gleaned from Junius S. Morgan II, Pierpont’s nephew and adviser.

Here, Satterlee made clear that the new building would house “a collection of rare volumes,” rather than a “reading library.” Estimating that Pierpont already held about ten thousand volumes, Satterlee instructed McKim to plan for growth and incorporate a librarian’s office.

Herbert Livingston Satterlee (1863–1947)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 19 May 1902, page 1

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

What Morgan Wants . . . (2)

In the early stages of the design process, J. Pierpont Morgan’s son-in-law Herbert Satterlee took the lead in communicating with McKim, passing on information gleaned from Junius S. Morgan II, Pierpont’s nephew and adviser.

Here, Satterlee made clear that the new building would house “a collection of rare volumes,” rather than a “reading library.” Estimating that Pierpont already held about ten thousand volumes, Satterlee instructed McKim to plan for growth and incorporate a librarian’s office.

Herbert Livingston Satterlee (1863–1947)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 19 May 1902, page 2

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

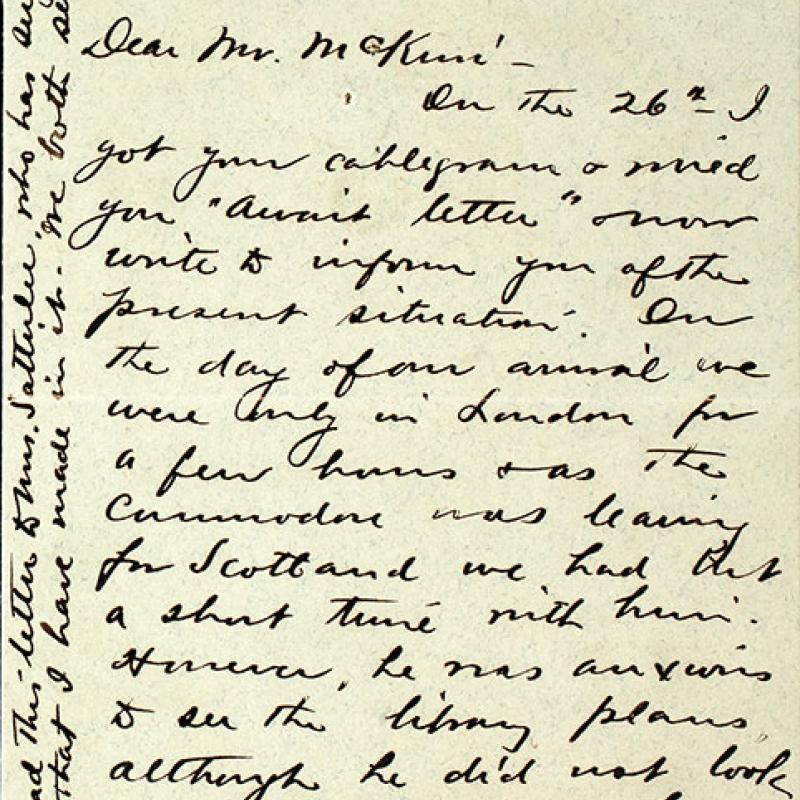

. . . Morgan Gets (1)

Louisa and Herbert Satterlee (Morgan’s daughter and son-in-law) sailed to England in summer 1902 to join Morgan for the coronation of Edward VII. They brought along McKim’s first designs for the Library. In this letter, Satterlee conveyed Morgan’s response to McKim: “They did not prove to be just what he wanted.”

Satterlee outlined Morgan’s wishes but reassured McKim: “I have formulated his objections with brutal brevity & ought to say that he liked the dignity of your building & its purity of design.” McKim went back to the drawing board, and by the end of the summer he had completed a design that Morgan embraced.

Herbert Livingston Satterlee (1863–1947)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, Aldenham Abbey, Watford, Hertfordshire, England, 29 July 1902, page 1

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

. . . Morgan Gets (2)

Louisa and Herbert Satterlee (Morgan’s daughter and son-in-law) sailed to England in summer 1902 to join Morgan for the coronation of Edward VII. They brought along McKim’s first designs for the Library. In this letter, Satterlee conveyed Morgan’s response to McKim: “They did not prove to be just what he wanted.”

Satterlee outlined Morgan’s wishes but reassured McKim: “I have formulated his objections with brutal brevity & ought to say that he liked the dignity of your building & its purity of design.” McKim went back to the drawing board, and by the end of the summer he had completed a design that Morgan embraced.

Herbert Livingston Satterlee (1863–1947)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, Aldenham Abbey, Watford, Hertfordshire, England, 29 July 1902, page 3

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

. . . Morgan Gets (3)

Louisa and Herbert Satterlee (Morgan’s daughter and son-in-law) sailed to England in summer 1902 to join Morgan for the coronation of Edward VII. They brought along McKim’s first designs for the Library. In this letter, Satterlee conveyed Morgan’s response to McKim: “They did not prove to be just what he wanted.”

Satterlee outlined Morgan’s wishes but reassured McKim: “I have formulated his objections with brutal brevity & ought to say that he liked the dignity of your building & its purity of design.” McKim went back to the drawing board, and by the end of the summer he had completed a design that Morgan embraced.

Herbert Livingston Satterlee (1863–1947)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, Aldenham Abbey, Watford, Hertfordshire, England, 29 July 1902, page 2

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

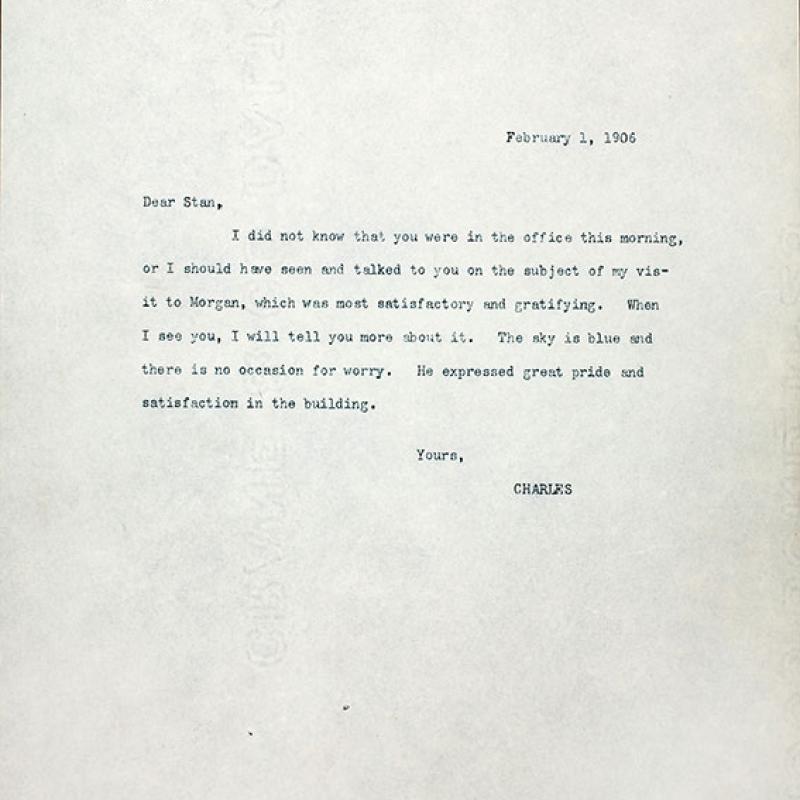

"The Sky is Blue and There is No Occasion for Worry"

Nearly four years after Morgan had invited McKim to design his Library, the building was substantially complete. McKim wrote to his partner Stanford White to express pleasure and relief. Morgan had been a demanding client, and the work had taken a toll on McKim.

Though White had secured an antique ceiling for Morgan’s Library, he was not involved in the building’s design. Five months after he received this letter, White was murdered at Madison Square Garden, one of his own creations.

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909)

Retained copy of a letter to Stanford White, New York, 1 February 1906

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

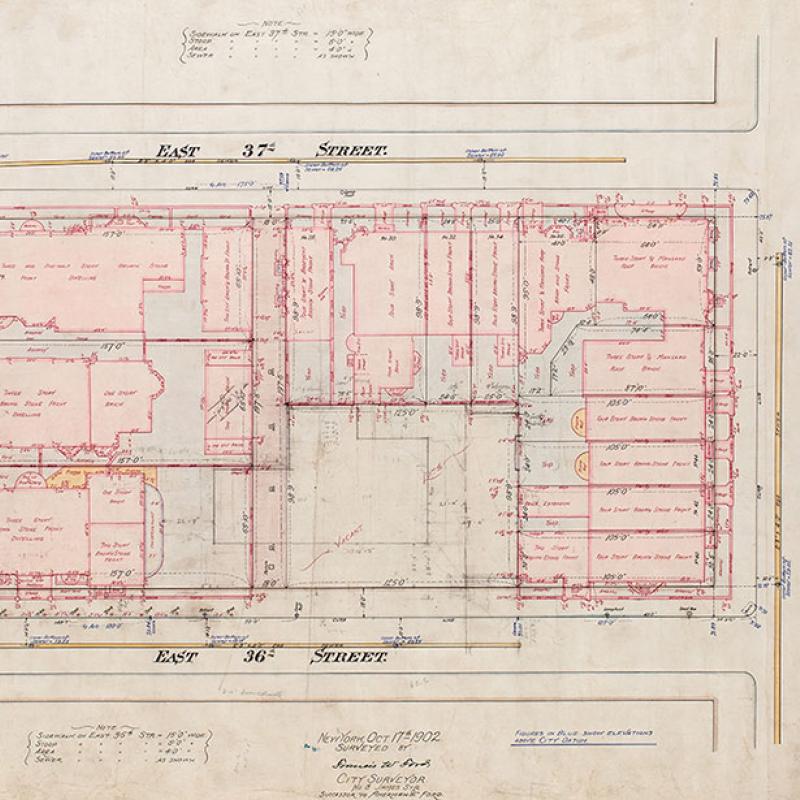

The Property Survey

This survey, created at the time of excavation, provides a detailed overview of the block on which the Library would be built. Morgan and his second wife, Fanny, lived at 219 Madison, on the northeast corner of 36th Street and Madison Avenue. The new Library would be constructed half a block to the east, on 36th Street between Madison and Park, where the large blank space appears on the map.

Francis W. Ford (1846–1904)

Survey of the block between 36th and 37th Streets and Madison and Park Avenues, New York, 17 October 1902

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

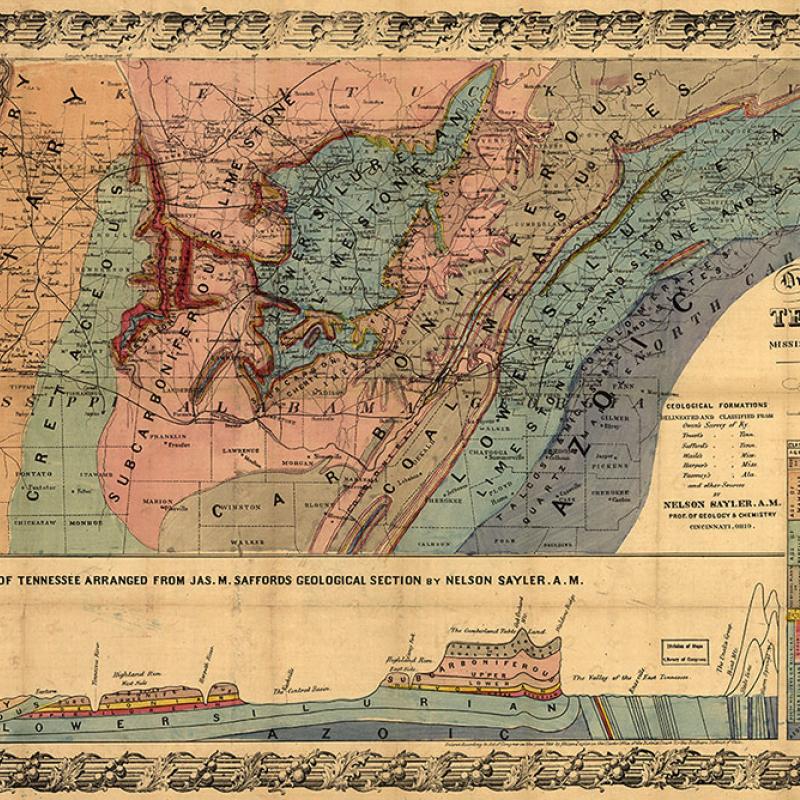

East Tennessee Stone

The lead builders of Morgan’s Library traveled to Tennessee in 1902 to scout stone. They chose to buy from the Knoxville Marble Company, run by John M. Ross, who was able to supply a large quantity of attractive and uniform stone. Morgan selected from several samples presented for his inspection. The heavy blocks were transported to New York via train—on the very railroads Morgan’s financial firm had reorganized through a nineteenth-century syndicate.

On this geologic map, Knoxville appears in the second colored band from the right at about 36° latitude, 84° longitude. The area is marked with the word “MARBLE.”

Nelson Sayler

An Outline Geological Map of Tennessee, Including Portions of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia

Cincinnati: E. Mendenhall, 1866

Library of Congress

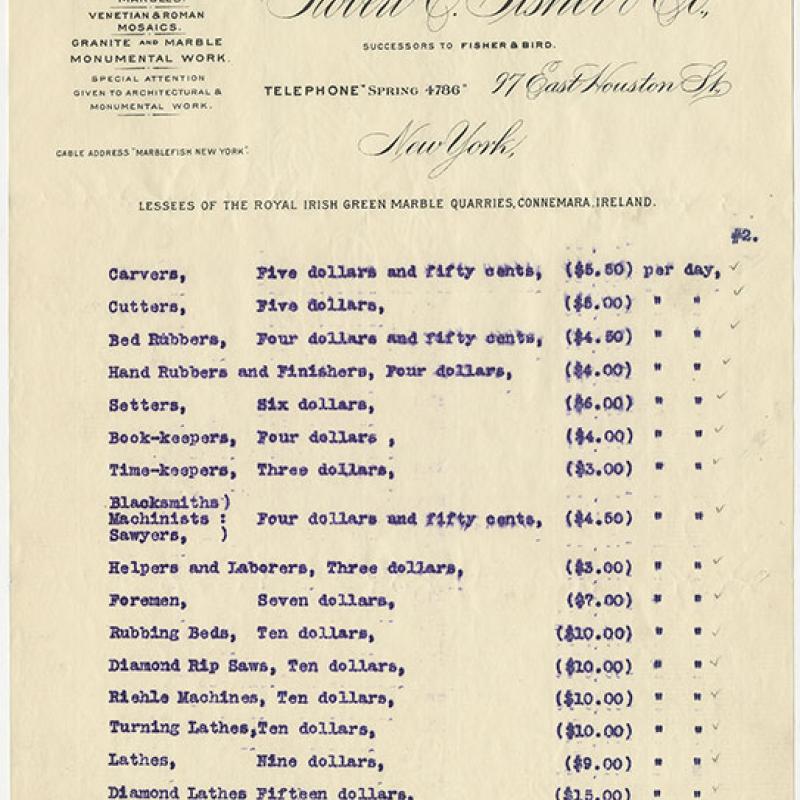

Stoneworkers' Wages

Virtually no records exist of the wages paid to the many people who built Morgan’s million-dollar Library. This letter is a rare exception: it lists typical day rates for various categories of workers employed by the stone contractor.

Skilled carvers were some of the higher-paid tradespeople, earning $5.50 per day. At the other end of the spectrum, laborers hoisting the stones on-site earned fifty cents a day under the employment of William Angus (a Scottish immigrant whose firm set the marble blocks). For comparison: the artist Hughson Hawley billed at a daily rate of $25 for his work on the watercolor rendering of the Library shown elsewhere in this exhibition; Beatrix Farrand, the landscape designer, charged $50 a day plus expenses.

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Page from a letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 7 February 1903

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

The Completed Library

From 1902 to 1906, hundreds of people worked to fulfill Morgan’s commission and realize McKim’s design, from the quarriers who extracted the stone in East Tennessee to the masons who set the blocks with exquisite precision. More than a century later, a contemporary team of specialists has honored their labor by restoring this well-made building, cleaning and repairing the façade, statuary, and front doors as well as the bronze perimeter fence shown in this early photograph.

Pach Brothers, New York

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1910

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 3278.1

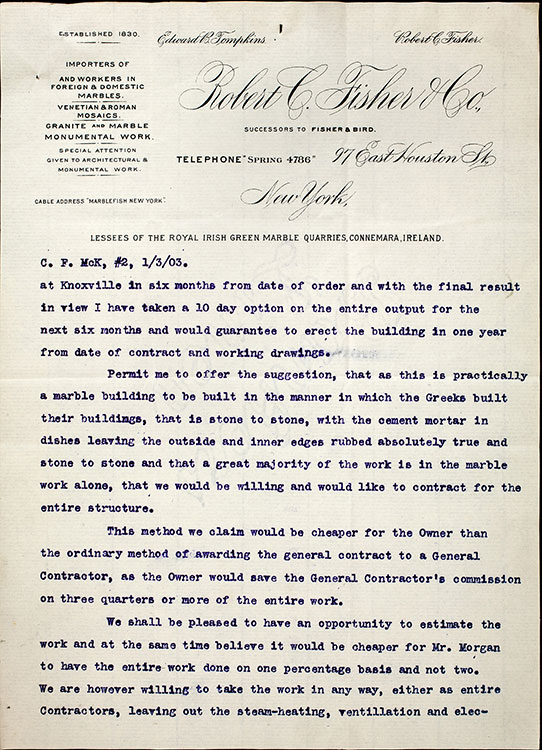

Building Without Mortar (1)

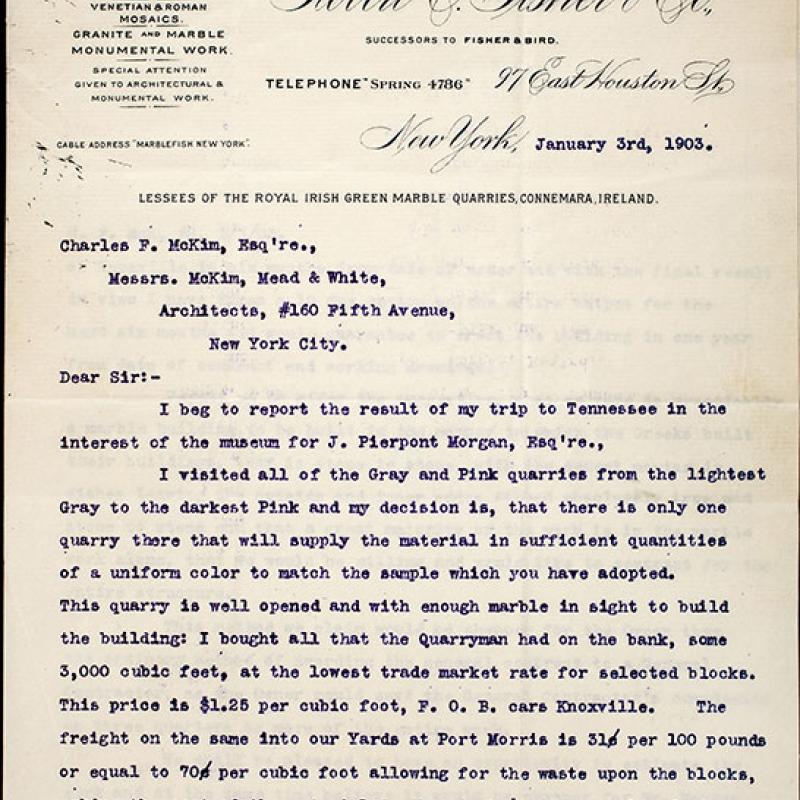

Robert C. Fisher & Co. secured the major contract to handle the exterior stonework (both construction and carving) for Morgan’s Library. In this letter, the firm’s president reported on his excursion to Knoxville, Tennessee, to source marble for the project. He called attention to the challenges inherent in McKim’s request to set the stone blocks without mortar: “This will be the only building ever built in modern time[s] as the ancients built and will require, as was required of them, the utmost accuracy and nicety known in mechanics.”

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 3 January 1903, page 1

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Building Without Mortar (2)

Robert C. Fisher & Co. secured the major contract to handle the exterior stonework (both construction and carving) for Morgan’s Library. In this letter, the firm’s president reported on his excursion to Knoxville, Tennessee, to source marble for the project. He called attention to the challenges inherent in McKim’s request to set the stone blocks without mortar: “This will be the only building ever built in modern time[s] as the ancients built and will require, as was required of them, the utmost accuracy and nicety known in mechanics.”

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 3 January 1903, page 2

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Building Without Mortar (3)

Robert C. Fisher & Co. secured the major contract to handle the exterior stonework (both construction and carving) for Morgan’s Library. In this letter, the firm’s president reported on his excursion to Knoxville, Tennessee, to source marble for the project. He called attention to the challenges inherent in McKim’s request to set the stone blocks without mortar: “This will be the only building ever built in modern time[s] as the ancients built and will require, as was required of them, the utmost accuracy and nicety known in mechanics.”

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 3 January 1903, page 3

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

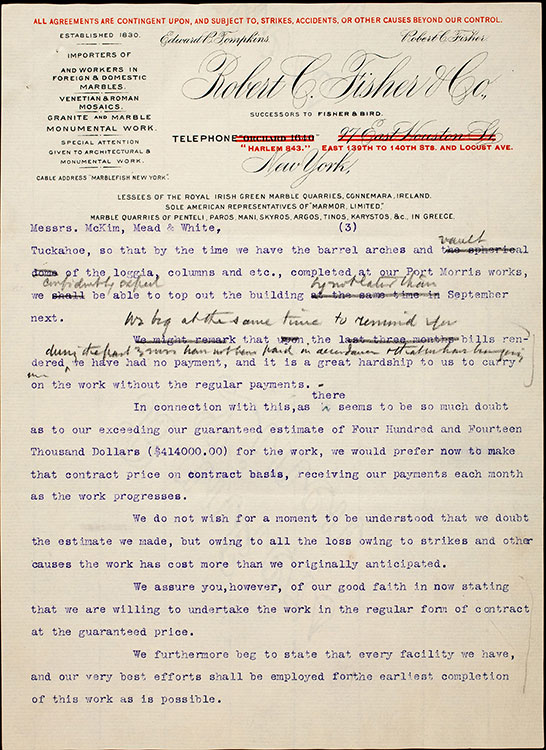

Untenable Working Conditions (1)

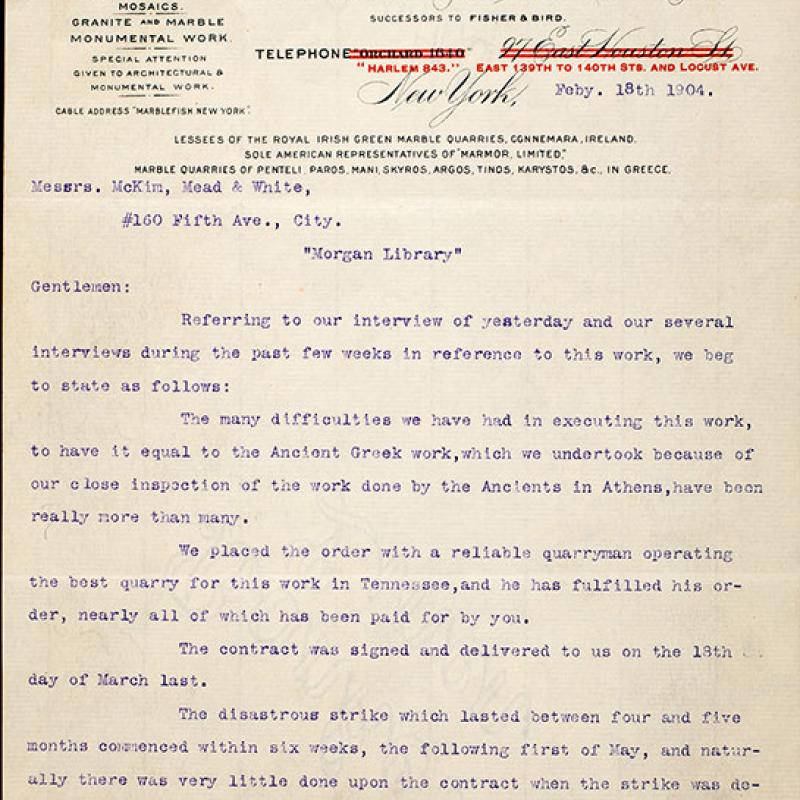

Just after construction had begun, a wave of strikes in the building trades brought work to a halt. By the time matters were resolved, freezing temperatures made it next to impossible to operate the stone shop. The marble contractor was forced to maintain enormous cash outlays, and McKim, Mead & White was withholding payment because work was behind schedule. Tompkins, the president of the marble contracting firm, outlined the dire situation in this letter to McKim.

In the end, these challenges and others (including unanticipated costs associated with the unorthodox stone-setting method McKim had stipulated) forced Fisher & Co. to mortgage its property for $80,000. The firm—one of the most distinguished in the trade—went bankrupt in 1911 after another wave of strikes.

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 18 February 1904, page 1

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Untenable Working Conditions (2)

Just after construction had begun, a wave of strikes in the building trades brought work to a halt. By the time matters were resolved, freezing temperatures made it next to impossible to operate the stone shop. The marble contractor was forced to maintain enormous cash outlays, and McKim, Mead & White was withholding payment because work was behind schedule. Tompkins, the president of the marble contracting firm, outlined the dire situation in this letter to McKim.

In the end, these challenges and others (including unanticipated costs associated with the unorthodox stone-setting method McKim had stipulated) forced Fisher & Co. to mortgage its property for $80,000. The firm—one of the most distinguished in the trade—went bankrupt in 1911 after another wave of strikes.

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 18 February 1904, page 2

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Untenable Working Conditions (3)

Just after construction had begun, a wave of strikes in the building trades brought work to a halt. By the time matters were resolved, freezing temperatures made it next to impossible to operate the stone shop. The marble contractor was forced to maintain enormous cash outlays, and McKim, Mead & White was withholding payment because work was behind schedule. Tompkins, the president of the marble contracting firm, outlined the dire situation in this letter to McKim.

In the end, these challenges and others (including unanticipated costs associated with the unorthodox stone-setting method McKim had stipulated) forced Fisher & Co. to mortgage its property for $80,000. The firm—one of the most distinguished in the trade—went bankrupt in 1911 after another wave of strikes.

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 18 February 1904, page 3

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Untenable Working Conditions (4)

Just after construction had begun, a wave of strikes in the building trades brought work to a halt. By the time matters were resolved, freezing temperatures made it next to impossible to operate the stone shop. The marble contractor was forced to maintain enormous cash outlays, and McKim, Mead & White was withholding payment because work was behind schedule. Tompkins, the president of the marble contracting firm, outlined the dire situation in this letter to McKim.

In the end, these challenges and others (including unanticipated costs associated with the unorthodox stone-setting method McKim had stipulated) forced Fisher & Co. to mortgage its property for $80,000. The firm—one of the most distinguished in the trade—went bankrupt in 1911 after another wave of strikes.

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 18 February 1904, page 4

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

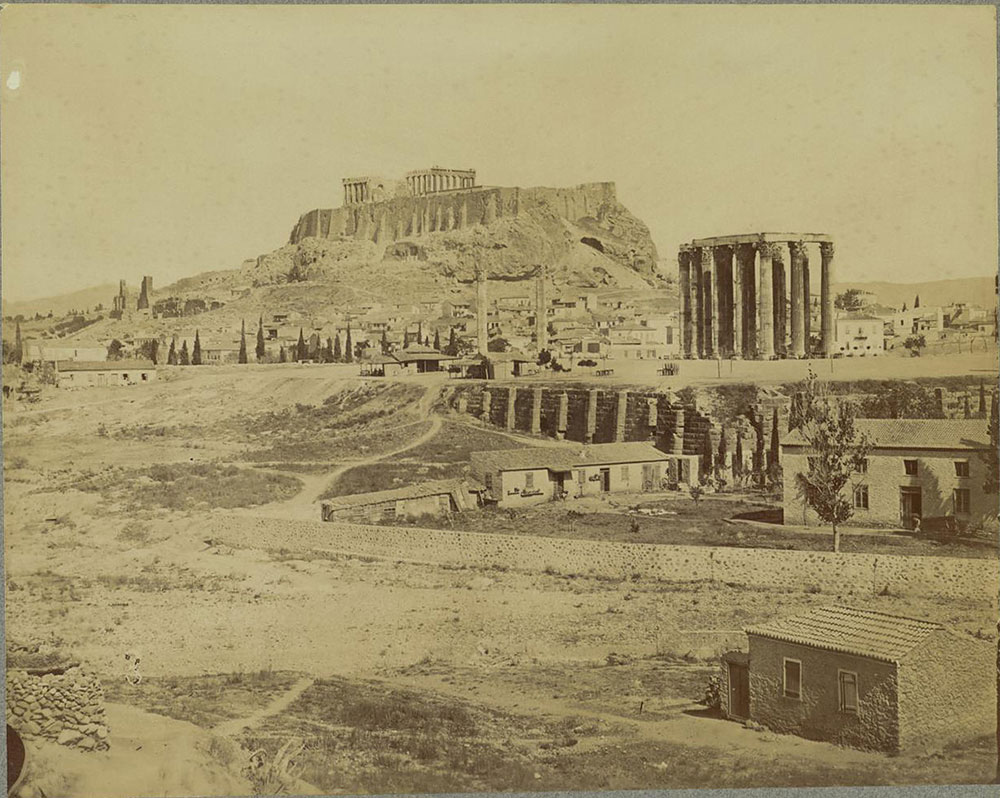

Inspired by the Ancients

McKim was dazzled by the buildings on the Acropolis in Athens. The stone blocks of the fifth-century-BC Erechtheum lined up face-to-face, mortarless, with such precision that even a thin blade could not be slipped into the seam. When he was engaged to design Morgan’s Library, McKim convinced the marble contractor, Robert C. Fisher & Co., to adapt ancient stone-setting methods, and Morgan agreed to cover the substantial additional cost.

These photographs, from a travel scrapbook in McKim, Mead & White’s records, depict the ancient architecture McKim so admired as he sought to create a contemporary building of comparable excellence.

Photographs from a McKim, Mead & White scrapbook depicting the Erechtheum and the Athenian Acropolis, ca. 1890s

Avery Classics Collection, Columbia University

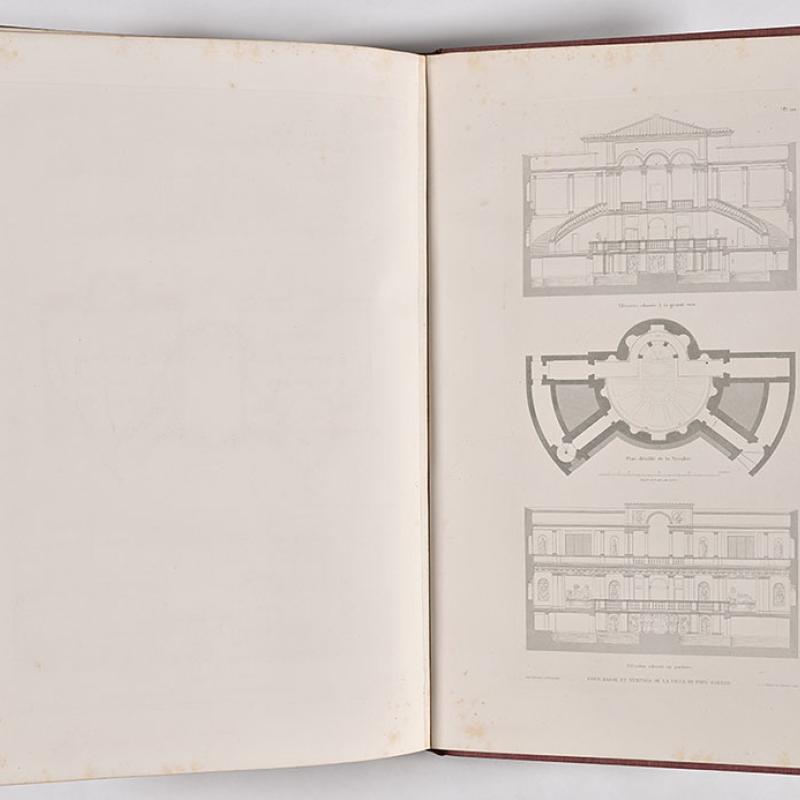

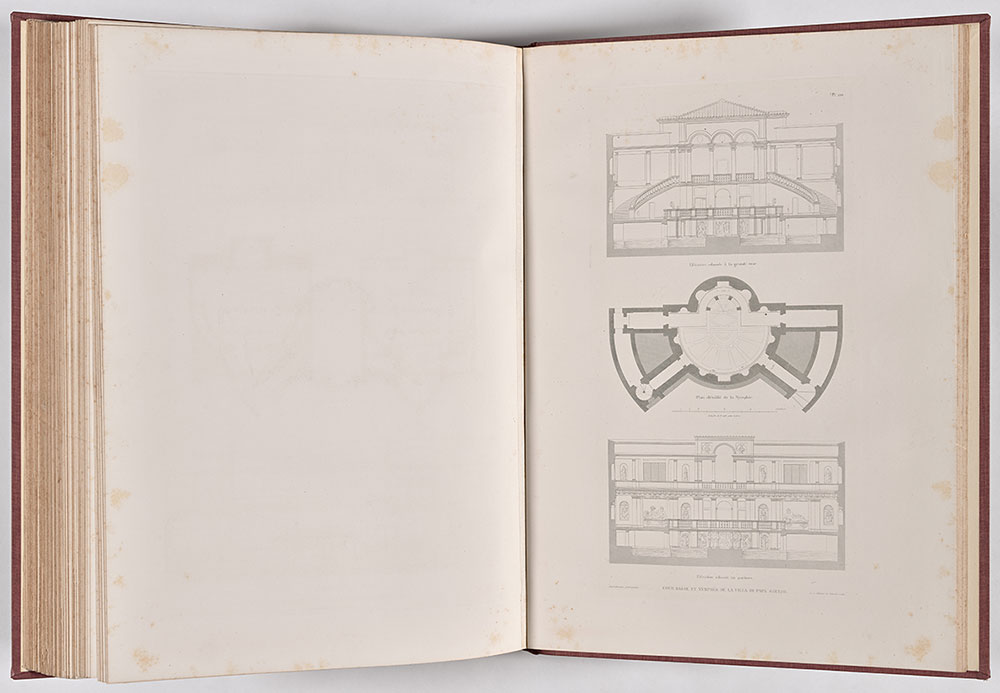

Mckim's "Office Bible"

McKim, Mead & White held an impressive library that informed its design practice. McKim himself relied heavily on the nineteenth-century French architect Letarouilly’s compilation of line drawings of Roman buildings. This plate depicts the nymphaeum of the sixteenth-century Villa Giulia, designed largely by Bartolommeo Ammannati. The Renaissance building was a key historic precedent for the façade of Morgan’s Library. McKim inscribed this copy to nineteen-year-old Lawrence Grant White, son of Stanford White, in 1906—just as Morgan’s Library was being completed and not long after Lawrence’s father was murdered. Lawrence was then an undergraduate at Harvard; he would go on to join the firm and have a distinguished architectural career himself.

Paul Letarouilly (1795–1855)

Édifices de Rome moderne; ou recueil des palais, maisons, églises, couvents, et autres monuments publics et particuliers les plus remarquables de la ville de Rome, vol. 2

Paris: Morel et Cie, 1874

Avery Classics Collection, Columbia University

Built on Lenape Land

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library stands on land that is part of Lenapehoking, the ancestral and spiritual homeland of the Lenape people. The marble blocks of which the Library was constructed were quarried on the ancestral lands of the ᏣᎳᎫᏪᏘᏱ Tsalaguwetiyi (Cherokee, East) and S’atsoyaha (Yuchi) peoples.

The Exterior

J. Pierpont Morgan commissioned the Library during an age of conspicuous opulence among his affluent peers. The new building cost him just over $1,011,000 (about $32 million today)— a figure that does not include his purchases of two houses that were demolished to create the large lot. This photograph depicts the Library (center) and the Morgans’ Manhattan home at the corner of 36th Street and Madison Avenue (far left).

Though the Library is stylistically distinct from the structures around it, Morgan insisted it be of an appropriate scale for the relatively residential neighborhood of Murray Hill. From the sidewalk, passersby could (and still can) look up to the light, spare, elegant facade, a testament to the skill of the many designers, artists, stone setters, carvers, and builders who brought the bookman’s paradise into being.

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, before 1924. Museum of the City of New York, X2010.18.286.

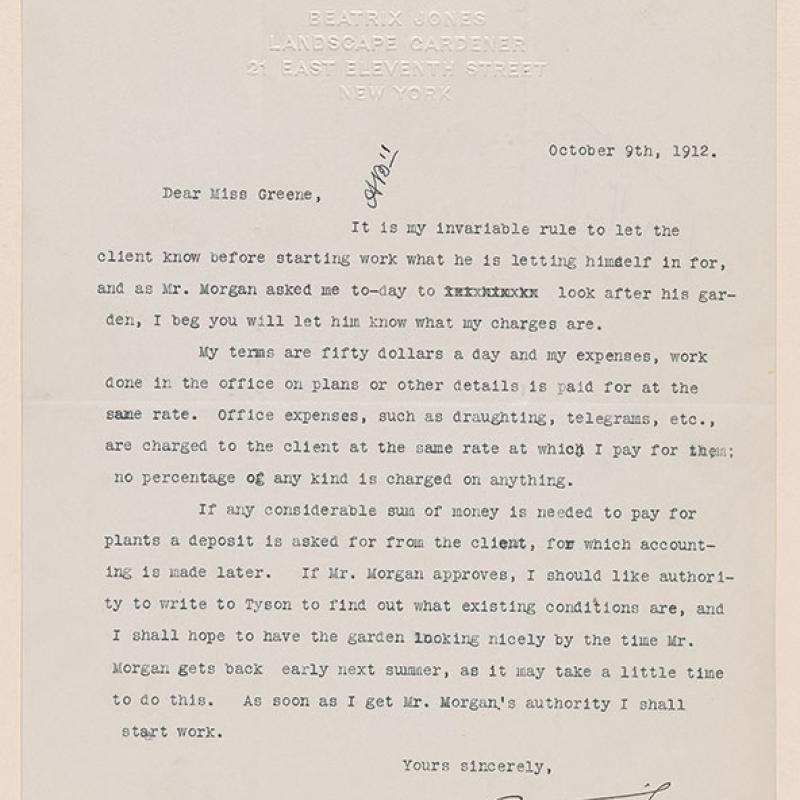

Beatrix Farrand, Landscape Gardener

In 1912 Morgan engaged Beatrix Jones (later Farrand), a friend of McKim’s, to landscape the grounds of his Manhattan property. In this letter, she outlined her terms to Belle da Costa Greene, Morgan’s librarian. Morgan died in March 1913 and never saw his garden “looking nicely,” as Jones had hoped he would.

Greene and Jones were the only two women who held prominent positions during the early years of the bookman’s paradise. Both went on to become national leaders in their respective fields.

Beatrix Jones (later Farrand, 1872–1959)

Letter to Belle da Costa Greene, New York, 9 October 1912

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1310

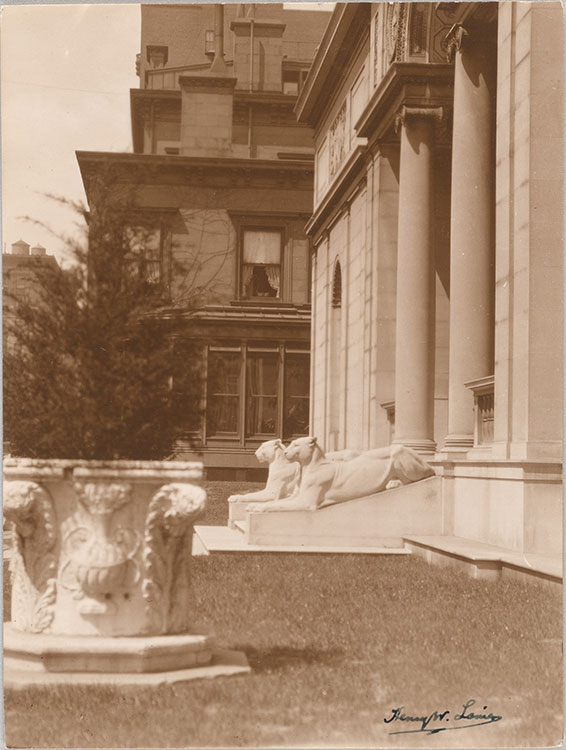

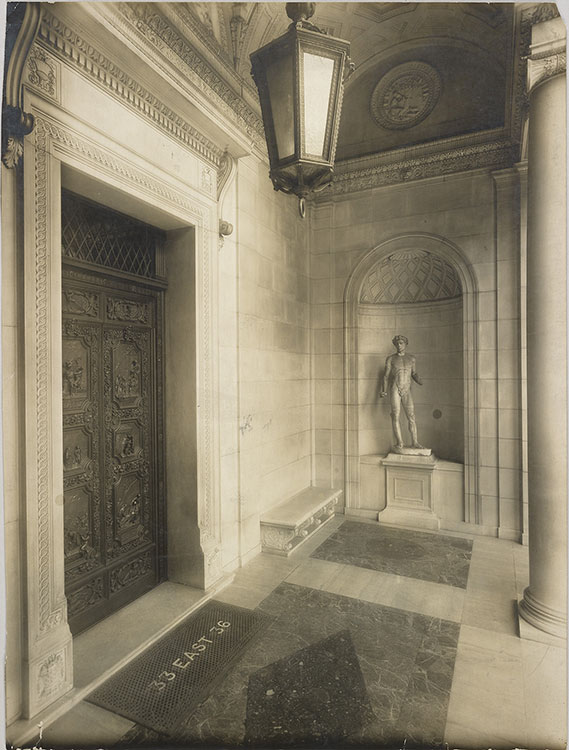

The Loggia

During Morgan’s day, visitors to his Library entered through a bronze gate along 36th Street and ascended a short flight of steps to the loggia, pictured here. As they approached the massive doors, they stepped across slabs of rose and green marble, the only touches of color against the pink-white blocks of the building’s exterior. Looking up, they would have seen a massive bronze lantern hanging from a vaulted ceiling adorned with marble carvings of notable printers’ marks (emblems).

Morgan purchased the antique statues in the lateral niches through a dealer in Rome in 1909; they were not part of McKim’s design

.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

Portico of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print