Holbein: Capturing Character

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543) was among the most versatile and inventive European artists of the sixteenth century. Born in the German city of Augsburg, he achieved early success in the humanist milieu in Basel, Switzerland, and later became the preeminent portraitist of members of the Tudor court in England. Holbein and his patrons understood the power of a beautifully executed, persuasive portrait. Through his close attention to sitters’ features and inclusion of inscriptions, mottoes, and emblems, Holbein not only conveyed truthful likenesses but also celebrated the individuals’ identities, communicating their lineages, values, aspirations, and achievements.

Holbein worked closely with Erasmus of Rotterdam, Thomas More, and other esteemed scholars in Renaissance Europe as both a portraitist and book illustrator. The book, with its ability to preserve and revive ancient texts and promulgate new ones, became the period’s humanist symbol par excellence, which many patrons wanted displayed in their portraits. Holbein was also active as a designer of personal jewels, which could serve as small declarations of the wearer’s taste, beliefs, and erudition. Featuring examples from the artist’s diverse output alongside select works by his Northern contemporaries, Capturing Character explores Holbein’s contributions to Renaissance portraiture and celebrates the era’s sophistication and visual splendor.

Holbein: Capturing Character is organized by the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, and the Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

The Morgan’s presentation of Holbein: Capturing Character is made possible by major support from the Drue Heinz Charitable Trust and the William Randolph Hearst Fund for Scholarly Research and Exhibitions, and by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom.

Generous support is provided by the Lucy Ricciardi and Family Exhibition Fund, the Christian Humann Foundation, T. Kimball Brooker, Joshua W. Sommer, Beatrice Stern, Alyce Williams Toonk, the Robert Lehman Foundation, the Robert Lehman Fund for Exhibitions, and The Gilbert & Ildiko Butler Family Foundation. Additional support is provided by the Berger Collection Education Trust,the Achelis and Bodman Foundation, the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, Rudy and Sally Ruggles, the Tavolozza Foundation, Barbara G. Fleischman, Robert Dance, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, and Mr. and Mrs. Randall Barbato. The exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Overview

Gallery Images

Biography

1497/98—Hans Holbein the Younger is born in Augsburg, Germany. The second son of the painter Hans Holbein the Elder (ca. 1460–1524), he is trained in his father’s workshop.

1515—Hans the Younger moves to the Swiss city of Basel alongside his older brother, Ambrosius, and launches his career as an independent painter and print designer the following year.

1519—Ambrosius, who was also active as an artist, dies. Hans the Younger marries Elsbeth Schmidt-Binzenstock.

1523—Holbein paints his first portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam, beginning a decades-long collaboration with the esteemed humanist.

1524— The artist visits France, likely hoping to obtain a position at the court of King Francis I.

1526—Equipped with letters of introduction from Erasmus to humanists Pieter Gillis in Antwerp and Sir Thomas More in London, Holbein travels to England via Antwerp. After two productive years, he returns to Basel.

1532—The turmoil that accompanies the Protestant Reformation and a dearth of significant commissions in Basel lead Holbein to pursue his fortunes once again in England.

1536—Around this time, Holbein is appointed court painter to King Henry VIII (1491–1547). He finds additional patrons among prominent members of the Tudor court as well as the community of German merchants living in London.

1543—Holbein dies in London at about the age of forty-five, probably a victim of the plague.

Erasmus, More, and the Humanist Portrait

Desiderius Erasmus (1466?–1536), also known as Erasmus of Rotterdam, was Europe’s first celebrity scholar, famous for his theological and philosophical writings. His ideas were widely and rapidly disseminated through the relatively new technology of the printing press. His books, such as the satirical Praise of Folly (Moriae encomium), were best sellers, read avidly across the social spectrum.

Although Erasmus believed that the written word was superior to the visual image, he used his portraits strategically to extend and deepen his influence. Erasmus’s personal emblem was Terminus, the Roman god of boundaries, known for resisting Jupiter, king of the gods. Artists, notably Holbein and Quentin Metsys, represented Terminus and Erasmus as a pair, so that the god’s portrayal as a stern-faced herm (stone pedestal with a head) came to embody the scholar’s formidable character. Erasmus was Holbein’s most important early supporter, and he introduced the painter to prominent individuals in England, including Sir Thomas More, a scholar and an advisor to King Henry VIII.

Erasmus of Rotterdam, Oil on panel

In 1523 Holbein developed a portrait of Erasmus that reflected the sitter’s scholarly reputation. Holbein portrayed Erasmus in three-quarter pose and dressed in a black robe and hat, emphasizing his intellectual character through the strong jawline and deep-set eyes. This circa 1532 painting of the then sixty-two-year-old humanist was based upon that earlier image but sensitively adjusted to convey Erasmus’s advanced age. His cheeks are more sunken, his forehead is wrinkled, and snow-white hair now peeks from underneath his cap. Such portrait roundels often served as intimate gifts between family members or close friends. This example was in the possession of Hieronymus Froben, son of the printer Johann Froben and Erasmus’s godson.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Erasmus of Rotterdam, ca. 1532

Oil on panel

Kunstmuseum Basel, Amerbach-Kabinett 1662; 324

Desiderius Erasmus was perhaps the first celebrity author in Europe, whose books on theology, philosophy, and the classics were published by the thousands on an almost annual basis. Although educated as a priest, he spent his early years as a peripatetic professor at universities in Cambridge, England, Turin, Italy, and Leuven, Belgium. A central figure of the European Renaissance, Erasmus corresponded with humanist luminaries from England to Italy, and counselled kings and church leaders.

Although Erasmus often argued for the primacy of word over image in the representation of an individual, he had a clear understanding of the power of the visual arts. He commissioned the artists Quentin Metsys and Albrecht Dürer to portray him as a scholar and author, but it was Holbein the Younger who created the de facto portrait of the great humanist. The artist and his Basel workshop produced multiple images of Erasmus, including this small roundel of the older Erasmus, attributed exclusively to the hand of Holbein himself. Devoid of any overt symbols or objects, the portrait focuses upon the face of the scholar—the man himself—rather than his occupation.

Kunstmuseum Basel - Jonas Haenggi

Signet Ring of Erasmus

Erasmus received this ring, set with an ancient carved gem, as a gift from his student Alexander Stewart, the archbishop of St. Andrews, Scotland. Erasmus believed the figure on the gem to be Terminus, the popular Roman god of boundaries known for his firm opposition to Jupiter, who tried to expel Terminus from the Capitoline Hill in Rome. Intrigued by this model of fortitude (and obstinance), Erasmus took Terminus as his personal emblem. The figure on the gem, however, has now been identified as Dionysus, god of wine.

Unknown maker

Signet Ring of Erasmus of Rotterdam (and modern impression), before 1509

Gold and carnelian (Roman gem, 1st century AD)

Historisches Museum Basel; 1893.365

©Historisches Museum Basel, Peter Portner

Seal of Erasmus of Rotterdam

Erasmus had this seal made to press his emblem into the warm wax that fastened his correspondences and other documents. Here Terminus is represented simply as a herm, a pedestal with a head. An inscription on the base identifies the Roman god while his head is framed by an abbreviated form of Erasmus’s personal motto, Cedo nulli (I yield to no one).

Unknown maker

Seal of Erasmus of Rotterdam (and modern impression), ca. 1513–19

Silver

Historisches Museum Basel; 1893.364

©Historisches Museum Basel, Peter Portner

Erasmus of Rotterdam, Engraving

Albrecht Dürer depicted the humanist scholar standing in his book-filled study and writing a letter. Although the inscription asserts that the likeness was “done from life,” the two men did not meet for an in-person sitting. Instead, Dürer based the portrayal on a drawing he had made during his meeting with Erasmus years earlier and on Quentin Metsys’s medal, while the composition evokes Holbein’s earlier portraits of the scholar writing at his desk. Ultimately, Erasmus did not care for Dürer’s representation and complained about it to friends.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1526

Engraving

Inscribed on the wall panel behind Erasmus, in Latin and Greek: The likeness of Erasmus of Rotterdam, done from life by Albrecht Dürer. His writings present a better portrait / 1526 / AD

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Rosenwald Collection; 1943.3.3554

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Portrait Medal of Erasmus of Rotterdam

Portrait medals were a form of portable sculpture popular in the Renaissance. Erasmus commissioned the design for this large and impressive medal from the Antwerp painter Quentin Metsys, who combined Erasmus’s likeness with that of his emblem, the Roman god Terminus. Attired in a cap and collared robe, Erasmus appears in profile, as if on an ancient coin. The surrounding inscription relates to the long-standing humanist debate about the respective merits of images and texts. It asserts that although the portrait is “from life,” and therefore reliable, Erasmus’s writings provide a truer representation of the author.

Seen in profile, facing into the winds of adversity, Terminus aligns with Erasmus’s portrait on the obverse. In Christian thought, Terminus was associated with the boundary between life and death. Turning the medal over, from the portrait of Erasmus to the image of Terminus, encouraged consideration of the inevitable passage from life to death, the true terminus.

Quentin Metsys (1465/66–1530), designer

Portrait Medal of Erasmus of Rotterdam (obverse), 1519, cast ca. 1524

Bronze

Inscribed around the perimeter, in Greek and Latin: His writings will give a better picture: His portrait taken from life.

Historisches Museum Basel; 1916.288

Quentin Metsys (1465/66–1530), designer

Portrait medal of Erasmus of Rotterdam, with Terminus (reverse), 1519, cast ca. 1524

Bronze

Inscribed around the perimeter and center, in Greek and Latin: Look to your end, however long your life—death is the final boundary of things.

Historisches Museum Basel; 1916.288

©Historisches Museum Basel, Peter Portner

Terminus, Device of Erasmus

In this painting, Holbein combined Erasmus’s portrait with his emblem, providing Terminus with Erasmus’s facial features. Seen through a stone opening, Erasmus/Terminus gazes across a featureless landscape. The golden disk behind his head represents divine radiance, underscoring the Christian meaning of the emblem for Erasmus: steadfast character and unwavering faith. This rare painting of a personal emblem by Holbein was probably intended to delight an admirer rather than to gratify Erasmus himself.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Terminus, Device of Erasmus, ca. 1532

Oil on panel

Inscribed on the background, in Latin: I yield to none

Inscribed on the base of the herm, in Latin: Terminus

Cleveland Museum of Art, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Sherman E. Lee in memory of Milton S. Fox; 1971.166

Terminus appears repeatedly in images associated with Erasmus. The deity, depicted as a bust emerging from a stone pillar, was venerated by ancient Romans as a protector of boundaries and frontiers. In Christian thought, Terminus was associated with the boundary between life and death.

For his personal emblem, Erasmus combined the iconography of the Terminus with the motto “concede nulli”—meaning I concede, or yield, to no one. Some of his contemporaries interpreted it as an expression of superiority and accused the scholar of intellectual and moral arrogance. Nevertheless, the image attained great renown and could even serve as the celebrated humanist’s visual surrogate. It was disseminated across Europe through prints, medals, and paintings, such as this exquisite roundel. Although Erasmus worked closely with Holbein and commissioned a number of works directly from the artist, the patron of this panel was most likely not the scholar himself but one of his many admirers.

The Cleveland Museum of Art

Erasmus of Rotterdam, Oil on panel

To satisfy the great demand for likenesses of Erasmus among the scholar’s many patrons and admirers, Holbein and members of his Basel workshop produced numerous versions of the same image. Like the other painted representation of Erasmus on view in the exhibition, this portrait shows the scholar in three-quarter profile against a neutral background. Holbein achieved a stately monumentality by filling the narrow panel with Erasmus’s form and by depicting his austere but luxurious clothing: the black hat and voluminous robe with fur collar and cuffs.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543) (and workshop?)

Erasmus of Rotterdam, ca. 1532

Oil on panel

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection; 1975.1.138

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

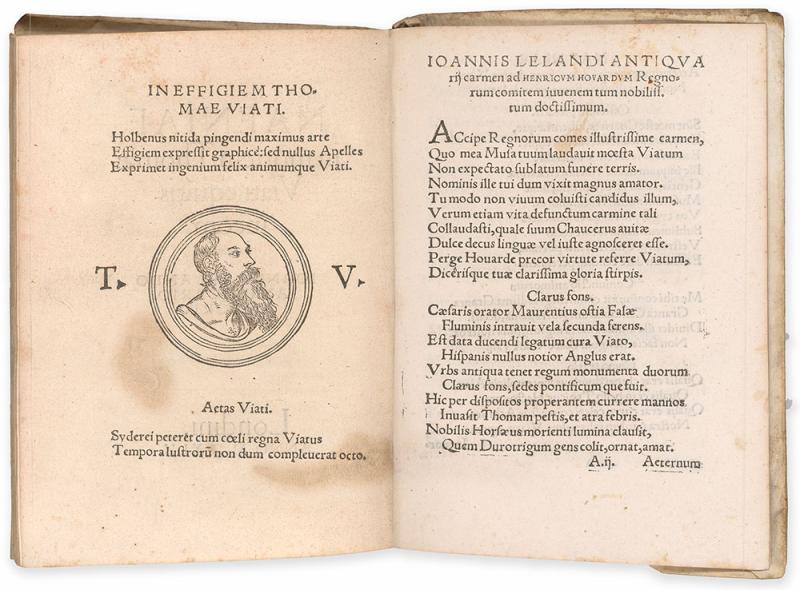

Erasmus of Rotterdam, Woodcut

Holbein designed this commemorative portrait of Erasmus following the latter’s death in 1536. Seen in full length and dressed in long robes, the scholar rests his hand on a sculpted herm of Terminus, which seems to cast a wily glance at the viewer. The lavishly decorated triumphal arch honors Erasmus, while the motifs of baskets and abundant garlands of fruit allude to his prolific scholarship. The text, added in movable metal type (not part of the woodcut itself ), commends the accuracy of the portrait: “If you have not seen Erasmus in life, then this image, executed from life, will show you how he looked.”

Veit Specklin (d. 1550), blockcutter, after a design by Hans Holbein the Younger

(1497/98–1543)

Erasmus of Rotterdam (“im Gehäus”), ca. 1538–40

Woodcut

Kunstmuseum Basel, Kupferstichkabinett; X.2128

Kunstmuseum Basel - Jonas Haenggi

Johann Froben

Despite its small scale, Holbein’s posthumous portrait of Johann Froben (1460–1527), originally enclosed in a carved frame with a lid, conveys the determined character of the Basel printer. It is one of the first known portraits of a European book printer, suggesting the importance of Froben to the printing industry as well as to Holbein’s career. Erasmus entrusted the publication of most of his texts to Froben, whose enterprise influenced book production throughout Europe. Froben hired Holbein to design woodcut illustrations for his publications beginning in 1516.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Johann Froben, ca. 1528–32

Oil and tempera on panel

Private collection

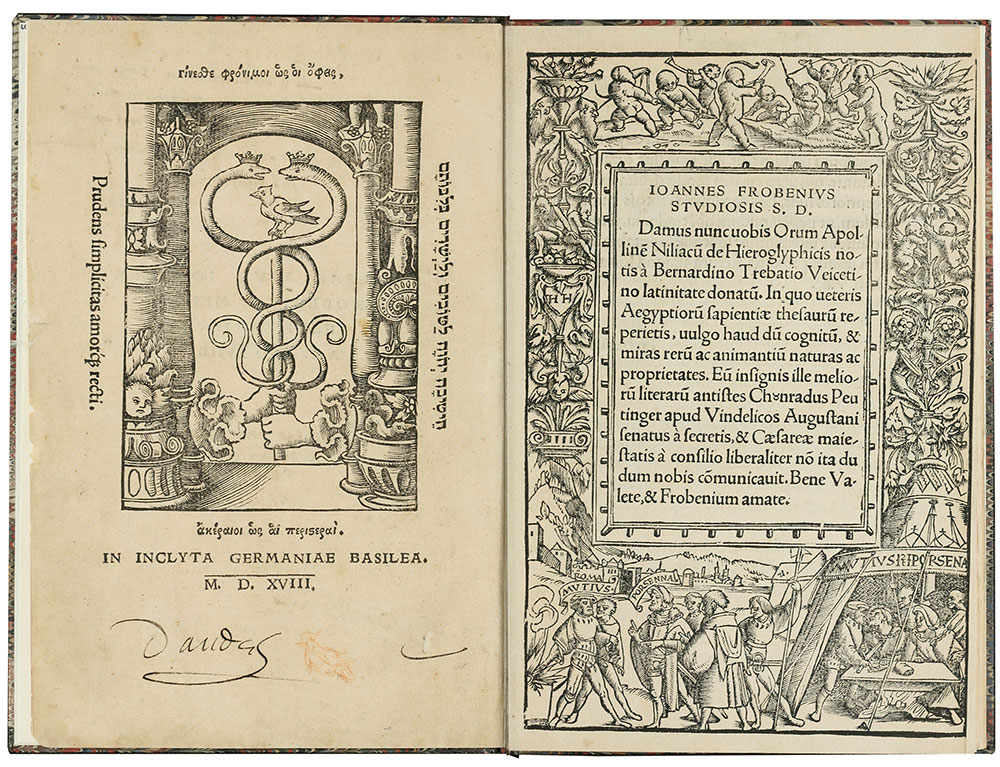

Hieroglyphica

Starting in 1516, Holbein designed decorative borders and illustrations for the Basel printer Johann Froben. This imagery, often derived from classical sources, was intended to appeal to a cultured clientele but did not directly relate to the text itself. Here, the shield in the left border contains the initials HH, which stand for either Hans Holbein or Hans Herman, the blockcutter who translated Holbein’s drawing into a relief woodblock for printing. Facing the title page is Froben’s printer’s mark, the trademark of his press. The caduceus (staff ) of the god Mercury represents industry and commerce, while the dove and serpents are derived from Matthew 10:16, which is printed in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew: “Be you therefore wise as serpents and harmless as doves.”

Horapollo (5th century AD)

Hieroglyphica

Woodcut by Hans Herman (act. 1516–23), after a design by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Basel: Johann Froben, 1518

Getty Research Institute, Special Collections, Los Angeles; 2864-782

Getty Research Institute

Henry VIII, King of England

The books Johann Froben printed were distributed across Europe, which meant that Holbein’s illustrations (if not his name) were disseminated as well. In 1521 the London printer Richard Pynson had an exact copy of the Mucius Scaevola border produced for his own use. Although the initials HH were retained, Pynson was likely more interested in emulating the quality of Froben’s production than Holbein’s artistic creation. In fact, many title-page borders used by the Basel printers—those designed by Holbein and others—were copied across Europe in efforts to capitalize on the notoriety of Basel printing.

Henry VIII, King of England (1491–1547)

Assertio septem sacramentorum adversus Martin Lutherum (Assertion of the seven sacraments in opposition to Martin Luther)

Woodcut after a design by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543) London: Richard Pynson, 12 July 1521

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of J. P. Morgan, 1935; PML 32270

Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (1478–1535) sat for this portrait at the height of his political career, shortly before he was promoted to lord chancellor, the highest-ranking office in Tudor England. Like his friend Erasmus, More was a prolific scholar, but Holbein presents him as an authoritative statesman, prominently adorned with a gold livery chain— a symbol of his service to the king. The S-shaped links might stand in for the motto “Souvent me souvient” (Think of me often), while a Tudor rose at the center is the traditional heraldic emblem of England. The portrait displays Holbein’s ability to render colors and textures—from More’s graying stubble to the opulent fur trim of his coat and the lush, voluminous red-velvet sleeves of his doublet.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Sir Thomas More, 1527

Oil on panel

The Frick Collection, New York, Henry Clay Frick Bequest; 1912.1.77

Erasmus was a close friend of Sir Thomas More and had stayed at the More house in Chelsea during his visits to London. A lawyer, scholar, and a powerful counselor to the King, More was Holbein’s most important supporter during his first visit to the British Isles. Upon his arrival in England, the artist carried letters of introduction from Erasmus to More in the hopes of using this personal connection to gain work in London and at the Tudor court. More introduced Holbein to several important courtiers who all commissioned portraits from him, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Warham, Royal Astronomer Nicholas Kratzer, and Sir Henry Guildford and his wife, Mary. Mary Guildford’s portrait is on view in the gallery to your left.

This is the canonical portrait of one of the key figures in sixteenth-century England. More is depicted in a three-quarter view, similar to Holbein’s favored pose for Erasmus. The man’s imposing form fills nearly the entire panel. The fairly dark palette of More’s fur-lined velvet robe and the green drapery behind him heighten the focus on the sitter’s face and intent gaze. The astonishing realism of Holbein’s portrayal extends to More’s salt-and-pepper whiskers.

Besides the painting of Thomas More is a copy of his most famous book, Utopia. Although divorce was legal in More’s Utopia, he did not support Henry VIII’s desire to separate from the Roman church so that Henry could divorce his wife, Catherine of Aragon, to marry Anne Boleyn. Henry saw this as treason, thus leading to More’s fall from power and execution in 1535.

The Frick Collection. Photo : Michael Bodycomb

Utopia

During a stay in Antwerp in 1515, Sir Thomas More began drafting a literary work that described a self-contained society on a fictional island. He coined the term “utopia” based on the ancient Greek term ou-topos, meaning “no place.” Both playful and serious, rooted in satire but also exploring complex philosophical ideas, the text was edited by his friend Erasmus and first published in Antwerp in 1516. The revised Basel edition, on view here, was published by Johann Froben under the continued guidance of Erasmus. It included a new map showing a bird’s-eye view of the island designed by Hans Holbein’s older brother, Ambrosius, and reused a title page border that Hans designed in 1516.

Sir Thomas More (1478–1535)

Utopia

Woodcut title page border by Hans Hermann (active 1516–23), after a design by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Basel: Johann Froben, November and December 1518

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1912; PML 19444

Capturing Likeness, Constructing Identity

In the late summer of 1526, Holbein set his sights on England, bearing letters of introduction from Erasmus to prominent local figures. His journey first took him to Antwerp, the leading economic and cultural hub in the Netherlands, where he encountered works by artists such as Jan Gossaert and Quentin Metsys, also on view in this gallery.

Holbein reached London that fall. Highly skilled portraitists were rare in the country, and he had few rivals. During his first stay, which lasted until 1528, Holbein produced several large-scale likenesses in which he delineated facial features with incisive accuracy. The painter placed his sitters in splendid spaces, surrounded by carefully selected and realistically rendered still-life elements. Through his command of the medium of oil paint, he captured a sense of immediacy and illusionism, seductively rendering a wide range of textures—from flesh to fur.

Mary, Lady Guildford

Mary Wotton, Lady Guildford (1499–after 1527), calmly gazes at the viewer from within a grand setting embellished by a marble column decorated in an Italianate style. She and her husband, Sir Henry Guildford, were among Holbein’s most important patrons during the artist’s first stay in England. While the sophisticated backdrop, jewelry, and fashionable dress, painted using lavish quantities of gold, denote Lady Guildford’s social status, the portrait also aims to communicate her piety and virtue. She clutches a religious book and a rosary, as if caught in a moment of reading or praying. The sprig of rosemary attached to her bodice is a traditional symbol of remembrance.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Mary, Lady Guildford, 1527

Oil on panel

Saint Louis Art Museum, Museum Purchase; 1:1943

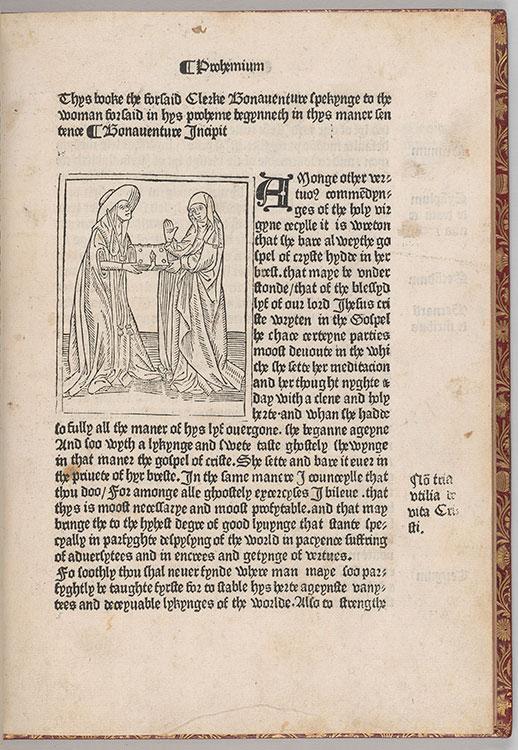

The Myrroure of the Blessyd Lyf of Jhesu Cryste

Written in an animated and accessible style, this popular work, long attributed to St. Bonaventure, encourages readers to reflect on mortality—hence the “mirror” in the English title—and contemplate the episodes of suffering that led up to Christ’s death. The woodcut illustration shows St. Bonaventure giving the book to a woman, suggesting that the text was specifically intended for a female readership or that this edition was particularly marketed to women. In Holbein’s portrait of Lady Guildford, the sitter holds what might be a copy of this text: an elegant green volume with a tasseled bookmark, labeled by Holbein with its Latin title, Vita Christi (Life of Christ), along the book’s top edge.

Johann de Caulibus (b. ca. 1376)

The Myrroure of the Blessyd Lyf of Jhesu Cryste

Translated by Nicholas Love (d. ca. 1423)

Westminster: William Caxton, ca. 1489–90

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased with the Bennett collection, 1902; PML 701

A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (Anne Lovell?)

Although this panel is one of Holbein’s masterpieces, the dignified sitter, dressed in an ermine fur cap and a fine silk shawl, remained unidentified until 2004, when the animals in the portrait were recognized as likely references to the Lovell family. Anne Lovell (née Ashby; d. 1539) was a wealthy English noblewoman whose husband, Sir Francis Lovell, served King Henry VIII. Her pet red squirrel, restrained by a silver chain and nibbling a hazelnut, alludes to the squirrels on the Lovell family crest. The starling on the left is a play on East Harling (commonly spelled as “Estharlyng” in Tudor times), the location of the Lovell estate in Norfolk, England. Technical studies have shown that Holbein added the animals at a late stage in the painting process, very likely at the request of the patrons.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (Anne Lovell?), ca. 1526–28

Oil on panel

National Gallery, London, bought with contributions from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund and Mr. J. Paul Getty Jnr. (through the American Friends of the National Gallery, London), 1992; NG6540

A solemn young woman holds a red squirrel in her hands, while a glossy-feathered starling perches on a branch near her shoulder. Although squirrels and starlings were common pets in England at the time, in this work, they also function as heraldic symbols and provide clues to the identity of the sitter. She is thought to be Anne Lovell—a wealthy and well-connected woman from Norfolk, whose husband Francis served King Henry VIII as an “esquire of the body,” or personal attendant.

Most sixteenth-century portraits of female sitters were originally created as part of a pair, with the woman placed to the viewer’s right side and gazing towards the left, in the direction of her husband. Anne Lovell’s portrait defies this convention, which suggests that it was likely painted as an independent work. The portrait might have been commissioned to celebrate the birth of the couple’s son Thomas in the spring of 1526.

Holbein’s facility with oil paint is evident throughout the portrait. Note, for instance, the dab of white paint that he added to the squirrel’s large dark eye, creating the impression of a bright, glassy surface. While the animal’s loosely painted chain falls through the sitter’s fingers, its fluffy tail reaches toward the opening in the woman’s chemise, resulting in a tactile juxtaposition of fur and flesh.

Some of the changes that Holbein made while painting are visible to the naked eye. You can see that he pulled the woman's hairline back at her temples, revealing more of her forehead. Other alterations are now hidden under layers of paint and can only be observed with the help of x-radiography. We know, for instance, that the artist had to change the position of the sitter’s arms fairly late in the painting process. This was done to accommodate the addition of the squirrel, which was likely requested by the patrons themselves.

© The National Gallery, London

Sir Nicholas Carew

Sir Nicholas Carew (ca. 1496–1539) carried out several important diplomatic missions in the service of Henry VIII. Made with a painted portrait in mind, this study exemplifies Holbein’s approach to drawing during his first stay in England. Working on a large scale and concentrating his attention on Carew’s face and beard, the artist modeled the man’s features by carefully blending black and colored chalks. Other parts of the drawing, such as the sitter’s upper body and the fluffy feathers that adorn his hat, are described using swiftly drawn yet virtuosic lines. The headgear is covered entirely in black chalk, but the letters gl, inscribed on the headband, would have reminded Holbein that the garment’s actual color was either yellow (gelb) or gold (gold).

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Sir Nicholas Carew, 1527

Black and colored chalks

Kunstmuseum Basel, Kupferstichkabinett, Amerbach-Kabinett 1662; 1662.34

Before 1539—when he was accused of participating in a conspiracy to overthrow King Henry VIII and beheaded at Tower Hill—Nicholas Carew enjoyed a very successful career as a courtier and diplomat. He was one of the king’s closest associates and undertook a number of important diplomatic missions, even accompanying Henry to his famous meeting with the French King Francis I at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520.

This large, brilliantly preserved drawing focuses on Carew’s physiognomy and luscious beard. It belongs to a small group of portrait studies in colored chalks, which Holbein produced during his first stay in England. Although the artist had begun experimenting with the medium only a few years prior, the skillful blending of different colors attest to his great mastery. Carew’s skin is modeled using a combination of red and black chalks, achieving an almost three-dimensional appearance. The armor and the opulent feathers that adorn his hat, on the other hand, are done more swiftly, with the greatest economy of means.

Kunstmuseum Basel Martin P. Bühler

Portrait of a Scholar

With his right hand raised and his left resting on a book and clutching a pair of glasses, the scholar in Quentin Metsys’s painting appears to have been caught at a moment of revelation. His dynamic pose and bold physicality distinguish the man from Holbein’s more stoic, seemingly withdrawn sitters, such as Erasmus and Sir Thomas More. The scholar is situated against a window, with a carefully constructed vista extending into the distance, including a river, a forest, mountains, and a fortified city. Such views, known as world landscapes, were a specialty of Antwerp painters in the 1520s.

Quentin Metsys (1465/66–1530)

Portrait of a Scholar, ca. 1525–30

Mixed technique on panel

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main; 766

Photo: Städel Museum

Francisco de los Cobos y Molina

Jan Gossaert depicted this self-possessed sitter with a red cross emblazoned on his doublet, a gem-encrusted jewel shaped like a scallop shell hanging around his neck, and an intricate hat badge. Despite such seemingly specific attributes, the man’s identity was lost until the late twentieth century, when he was recognized as Francisco de los Cobos y Molina (ca. 1475/80– 1547), the powerful secretary and advisor to Emperor Charles V. The identification was made by comparing the painting with the portrait medal of Los Cobos.

Jan Gossaert (ca. 1478–ca. 1532)

Francisco de los Cobos y Molina, ca. 1530–32

Oil on panel

Inscribed on hat badge, in Latin: Augusta Livia [wife of the Roman Emperor Augustus] V Carolus V [?]

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; 88.PB.43

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Portrait Medal of Francisco de los Cobos

Portrait medals, which unite a likeness, text (usually name and motto), and personal emblem, can play an important role in identifying distinguished individuals. This medal and its inscription reveal the subject of Jan Gossaert’s corresponding painting. Although it can be challenging to directly compare works of such different mediums, the men’s facial features, hairstyles, and beards appear strikingly similar. Moreover, in both images the sitter wears the scallop-shell pendant of the Order of Santiago, of which Los Cobos was comendador mayor (major commander).

Christoph Weiditz the Elder (ca. 1500–1559)

Portrait Medal of Francisco de los Cobos (obverse), 1531

Lead

Inscribed around the circumference, in Latin: To Francisco de los Cobos, great chancellor of the imperial army, privy councilor of Charles the fifth, in the year 1531

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection; 1957.14.1183.a

Christoph Weiditz the Elder (ca. 1500–1559)

Portrait Medal of Francisco de los Cobos, with a Man Riding toward a Cliff, Carrying a Scroll (reverse), 1531

Lead

Inscribed on the scroll, in Latin: Fate will find a way

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection; 1957.14.1183.b

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

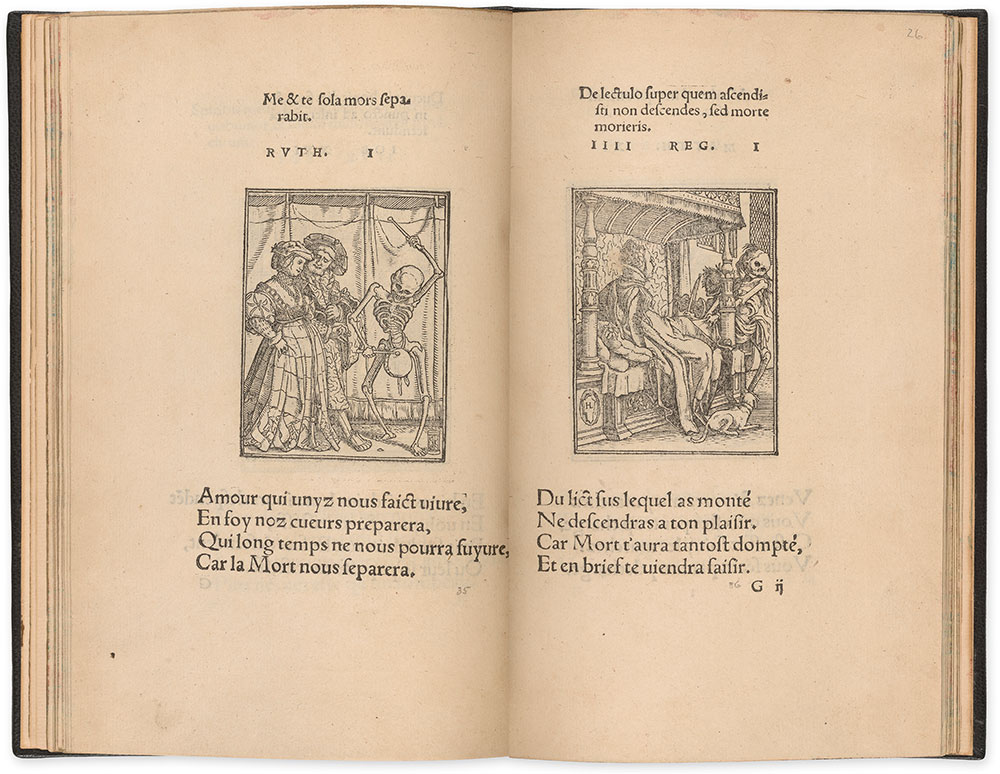

Holbein’s Dance of Death

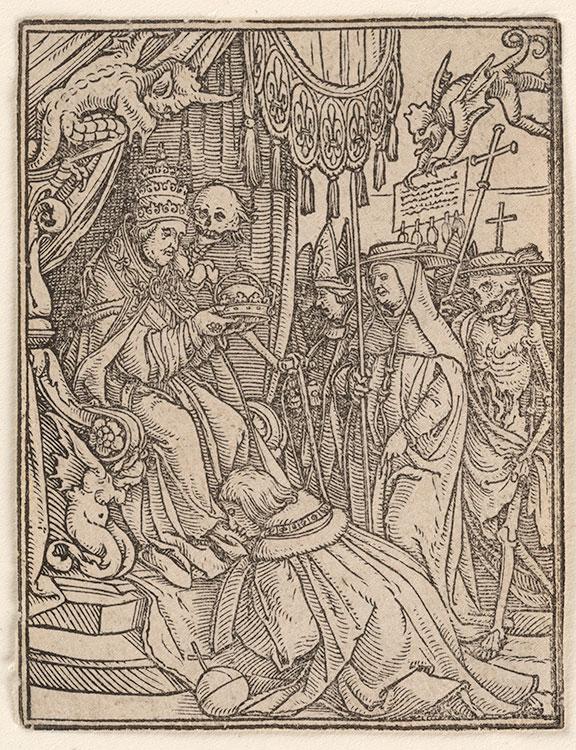

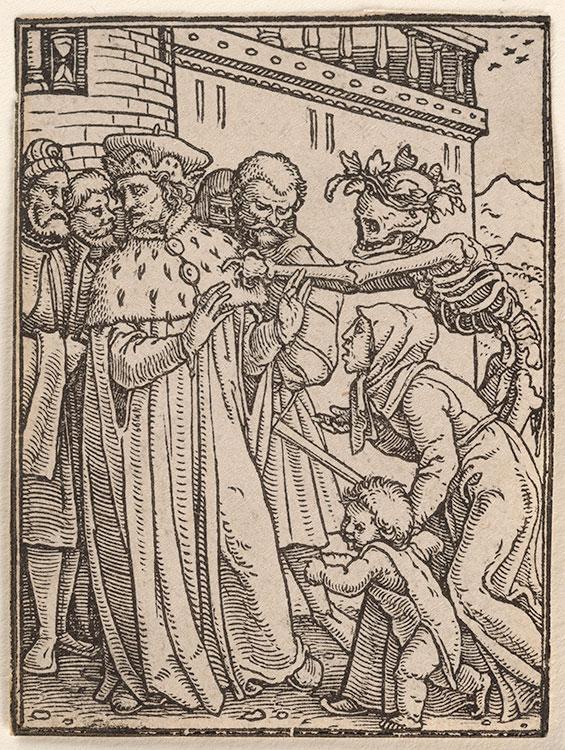

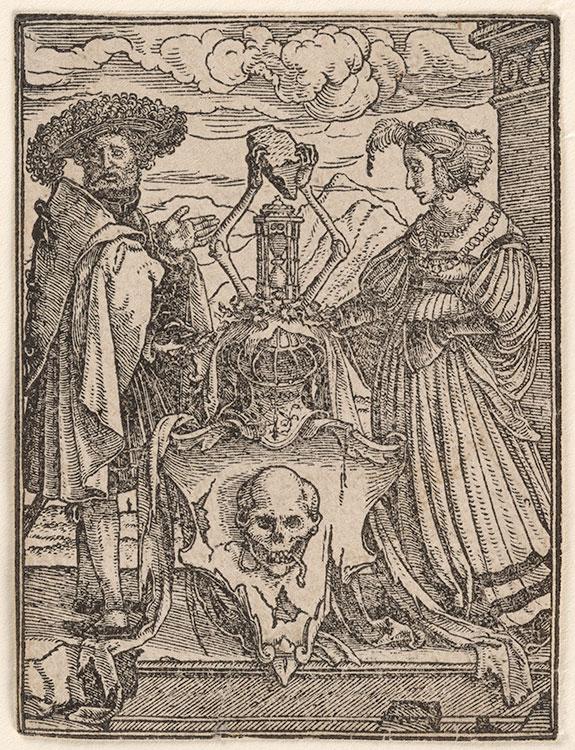

In the dance of death, an allegory common in medieval and Renaissance Europe, a skeleton “dances” with all members of society—from pope to peasant—as a reminder of their inevitable earthly demise. Depicted in church and cemetery murals as well as prayer-book illustrations, the motif was a positive and sympathetic prompt to prepare for a Christian death. This perspective on mortality relates such imagery to portraiture, which aimed to capture and preserve an individual’s likeness at a fleeting moment in time.

The creation of printed images was typically a collaboration between an artist who composed the illustrations and a blockcutter who transferred these drawings into a printable medium, such as woodcut. In the early 1520s, the Basel blockcutter Hans Lützelburger was commissioned to produce dance of death imagery for a new book, The Images of Death, and he turned to Holbein for the compositions. Holbein and Lützelburger’s designs transformed the traditional medieval series of stiff figures in two-dimensional settings into three-dimensional genre scenes full of allusions to contemporary life. As with his portraits, Holbein used specific emblems and objects to represent various members of society as Death leads them—passively, comically, or mockingly— in the dance.

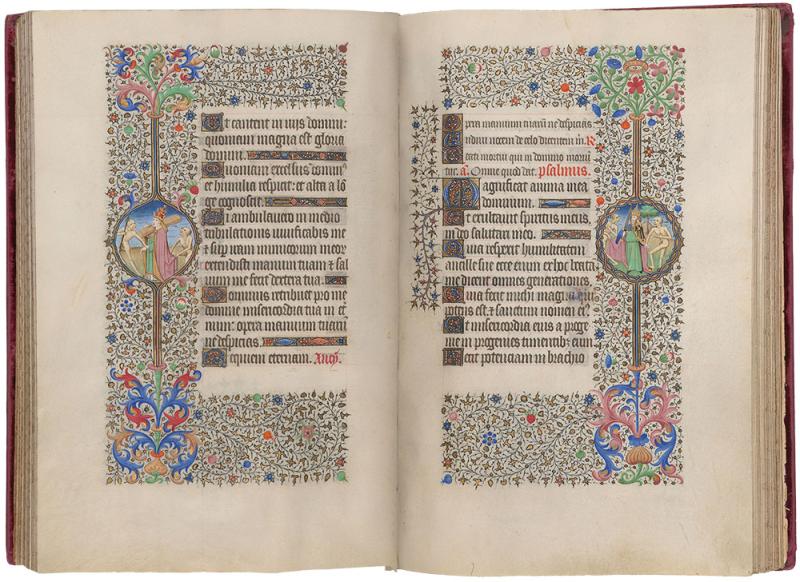

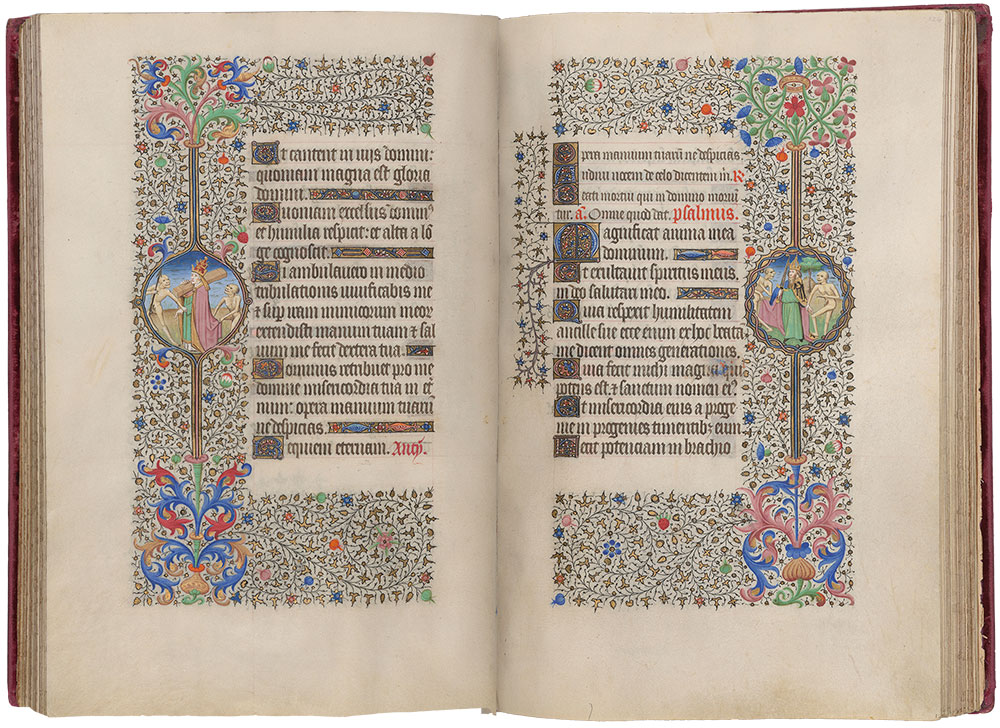

Book of Hours

Used as tools for devotion and preparing one’s soul for a Christian death, personal prayer books often featured dance of death imagery. The margins of this Book of Hours include fifty-six such scenes. The manuscript was produced in Paris, and the scenes are supposedly derived from the original dance of death mural, dating to 1424–25 (and destroyed in 1699), in the city’s Cemetery of the Holy Innocents. Here you can see the minuscule, simplistically rendered pope (left) and emperor (right). Unlike the Parisian mural, this dance of death excludes women, which might indicate that the original patron was male.

Book of Hours

Paris, 1430–35

Illuminated by Bedford Master and workshop (act. 1415–35)

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909; MS M.359, fols. 123v–124r

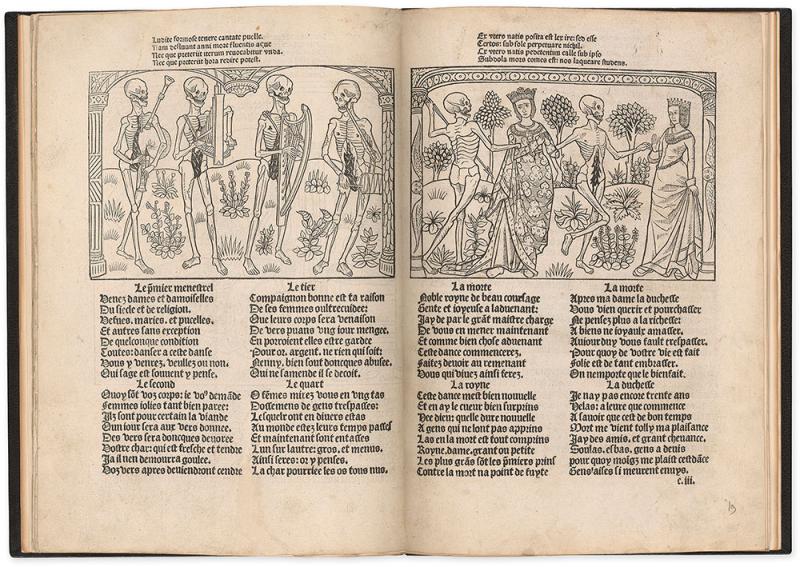

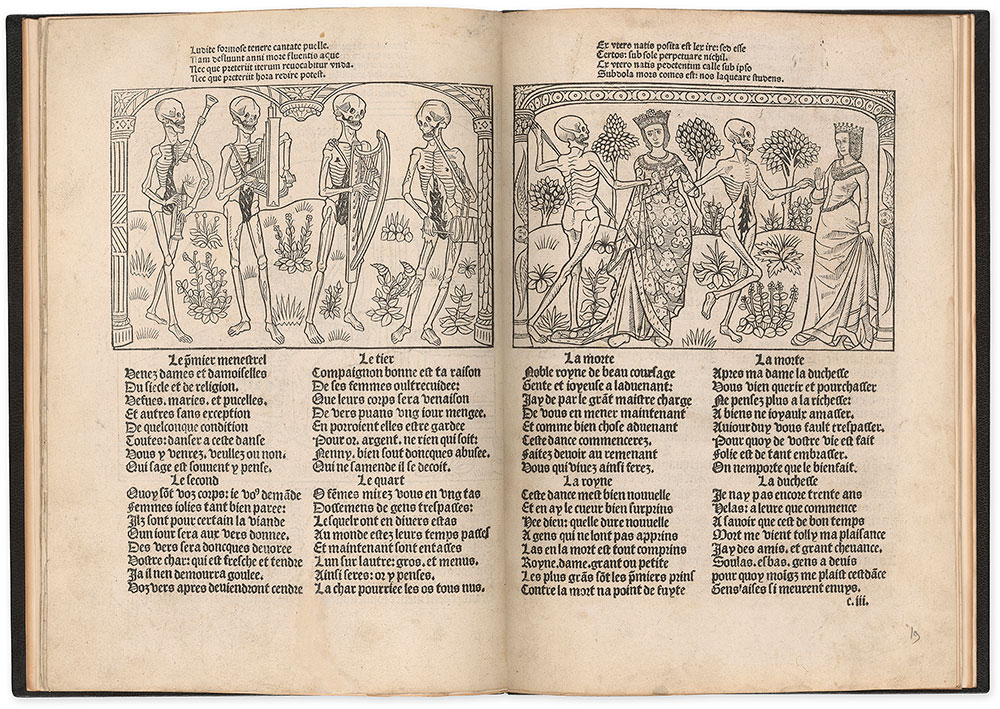

La danse macabre nouvelle

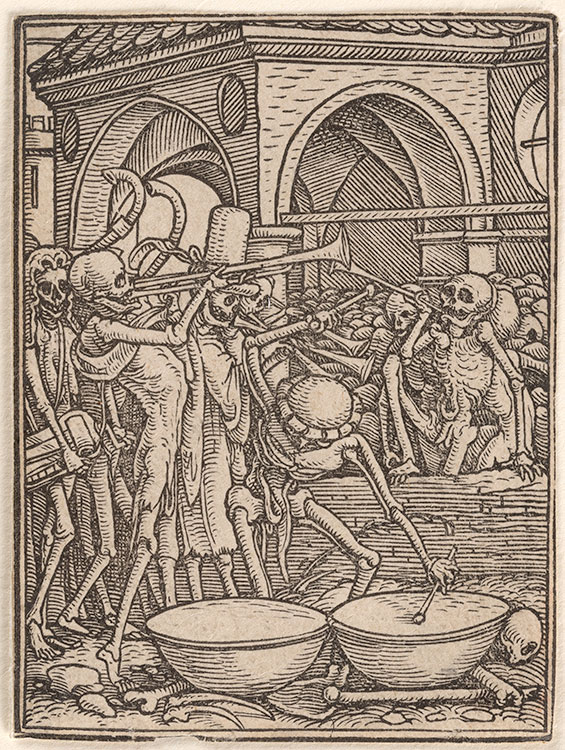

La danse macabre nouvelle, first printed in 1485 by Guy Marchant, is perhaps the closest reproduction of the Parisian cemetery mural in which dance of death imagery first appeared—most notably, the illustrations include the arcade from the architectural setting as a framing device. The text, also derived from the cemetery mural, is a dialogue wherein death indicates the inevitability of the dance while the protagonists variously bemoan their poorly spent lives and loss of material gain. The printed editions include a dance for men followed by a separate dance for women, each introduced with skeletons playing musical instruments. Produced four decades later, Holbein and Lützelburger’s illustrations would retain the skeletal musicians but intermingle men and women.

La danse macabre nouvelle (The new dance macabre)

Paris: Guy Marchant, 7 June and 7 July 1486

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1975; PML 75062

Book of Hours

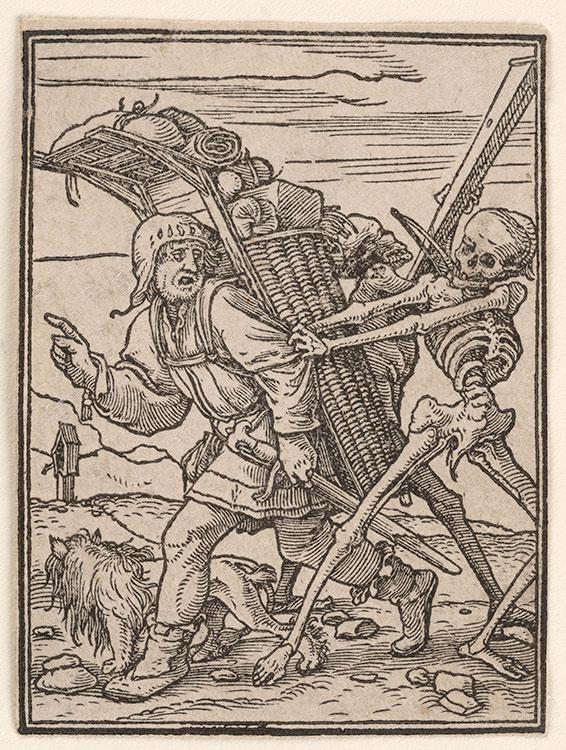

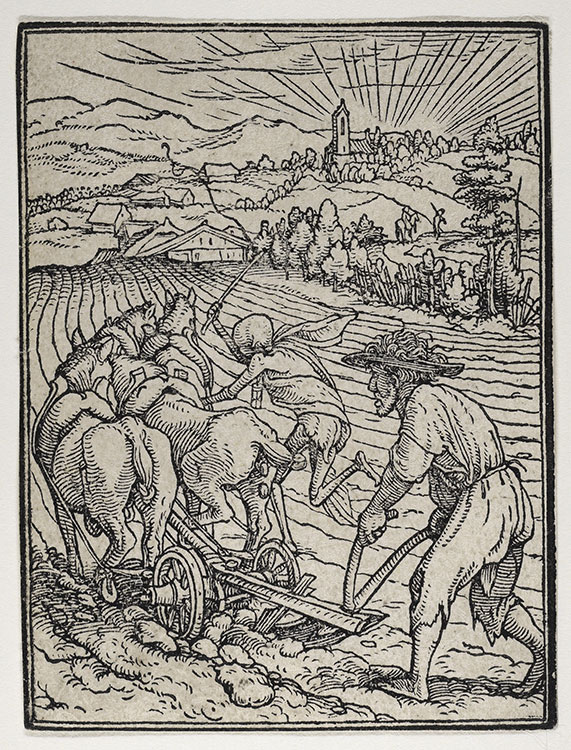

Prior to his collaboration with Lützelburger on the prints for Images of Death, Holbein traveled to France, hoping to find employment at the royal court. In Tours, Holbein encountered a workshop of manuscript illuminators, whose illustrations for Books of Hours provided inspiration for at least two death scenes. Holbein converted the workshop’s illustrations of the month of October, featuring a laborer plowing a field (shown in this later manuscript), into Death and the Plowman (or Peasant) for the printed series. In Holbein’s reinterpretation, a rather pastoral scene of agrarian life takes a sinister turn as Death whips the horses onward: the plowman’s toil leads to his demise.

Book of Hours

France, probably Tours, ca. 1530–35

Illuminated by the Master of the Getty Epistles (act. 1528–50)

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911; MS M.452, fols. 10v–11r

Images of Death

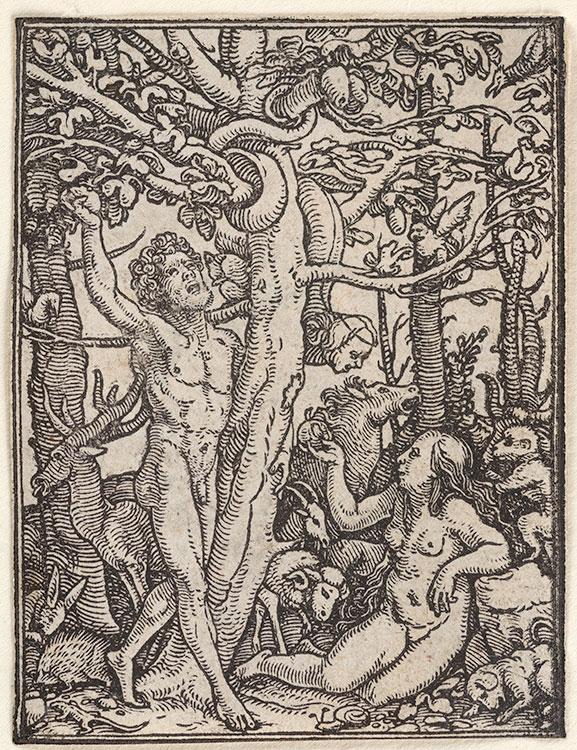

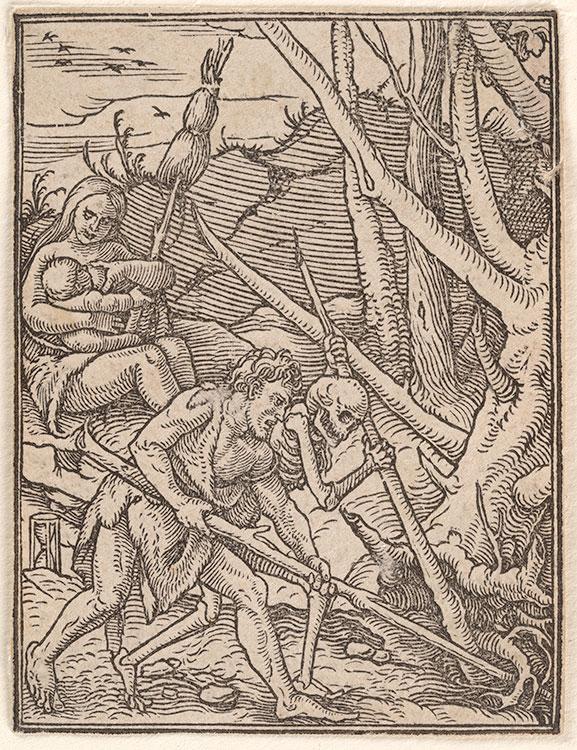

Lützelburger and Holbein reimagined the medieval dance of death into detailed genre scenes where Death catches people amid their daily routines. As in Holbein’s portraits, objects and emblems indicate individuals’ social strata or professions and in some cases mockingly aid in their demise. Lützelburger signed the bed frame in the image of the duchess (fourth frame [far right], top row, print five) with his initials, HL. Lützelburger was an exceptionally skilled blockcutter, more so than the other artists with whom Holbein had worked, and his abilities allowed for the best translation of Holbein’s compositions into print, especially at the small scale of this series.

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Images of Death, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.1–40

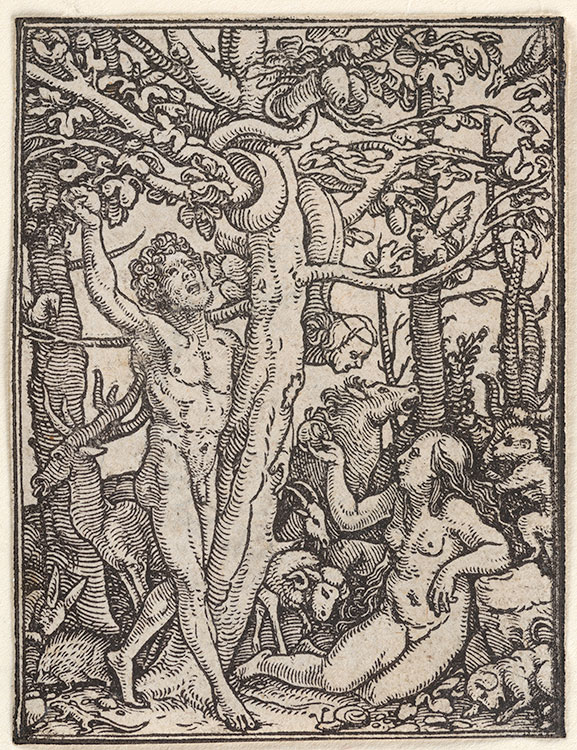

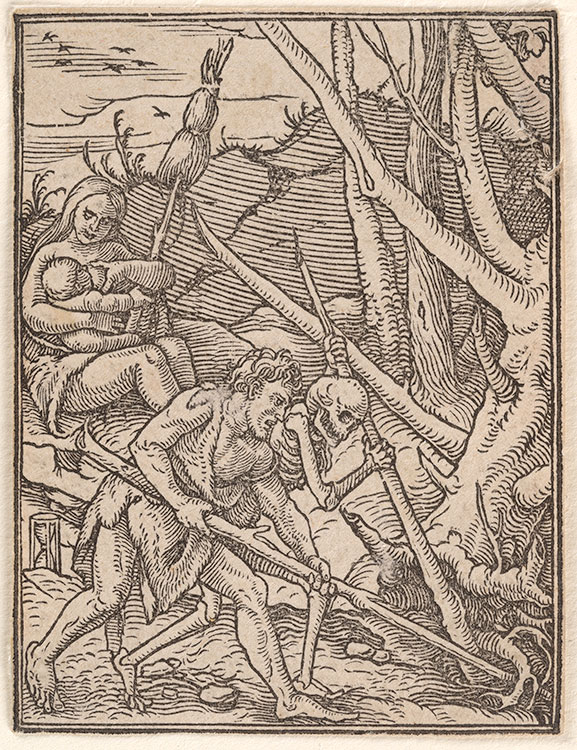

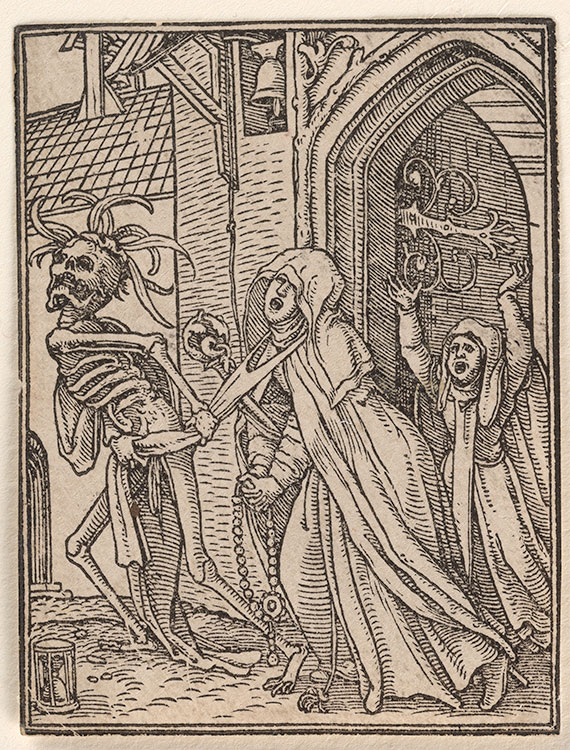

Contrary to what we might think today, during the Renaissance, the Dance of Death imagery was not considered morbid or scary. Rather, it served as a positive reminder to lead a good, devout life. While the earlier medieval tradition tended to represent the figures in the dance as rather unexpressive and static, Lützelburger and Holbein created a series full of action and high emotion, depicting the protagonists amid their daily routines.

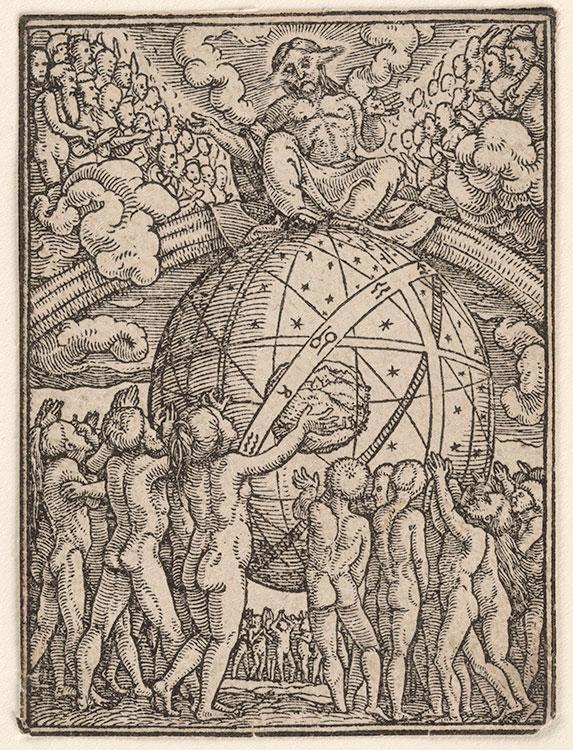

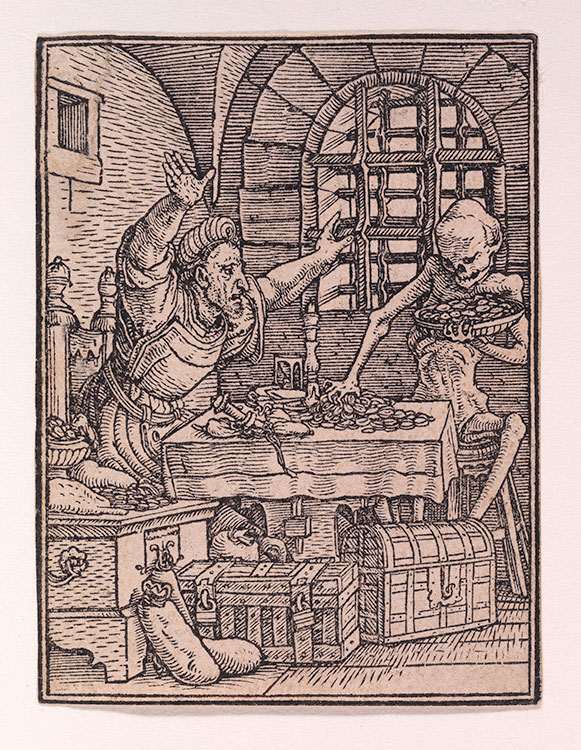

Death comes into the story of humanity after the Fall, when Adam and Eve are banished from the Garden of Eden. These events are narrated in the first four scenes. The successive thirty-six prints represent Death meeting members of every social class. Holbein varied the compositions for each figure and adapted the manner in which they met their fate. Some protagonists, like the Monk or Rich Man, scream and try to fight off Death. The Sailor, Knight, and Count all meet rather violent ends. Death seems to surprise the Nun meeting with her lover and the Bishop tending his flock. The Old Man and Old Woman are more passive in the acceptance of their awaited fates. Some scholars have found Protestant sympathies in the scenes, as with the demons who help the Pope to sell indulgences—a practice famously criticized by Martin Luther in the Ninety-five Theses.

This series is the masterpiece of both Holbein’s and Lützelburger’s print careers. In each other, the two artists found a collaborator of equal talent to their respective expertise: Holbein finally had a blockcutter who could expertly translate his drawings into relief print, and Lützelburger had a draftsman whose mastery of three-dimensionality could be translated into print by his extraordinary deftness of carving.

Creation of Eve

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Creation of Eve, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.1

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Fall (or Temptation of Adam)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Fall (or Temptation of Adam), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.2

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Expulsion from Paradise

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Expulsion from Paradise, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.3

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Adam Plowing

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Adam Plowing, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.4

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Skeletons Making Music (or the Cemetery)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Skeletons Making Music (or the Cemetery), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.5

Death and the Pope

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Pope, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.6

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Emperor

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Emperor, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.7

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

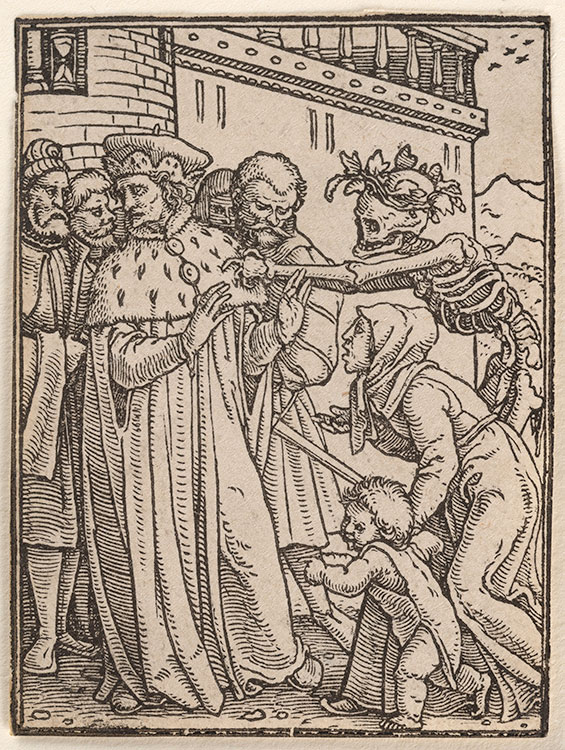

Death and the King

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the King, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.8

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Cardinal

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Cardinal, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.9

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Empress

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Empress, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.10

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Queen

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Queen, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.11

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Bishop

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Bishop, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.12

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Duke

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Duke, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.13

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Abbot

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Abbot, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.14

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

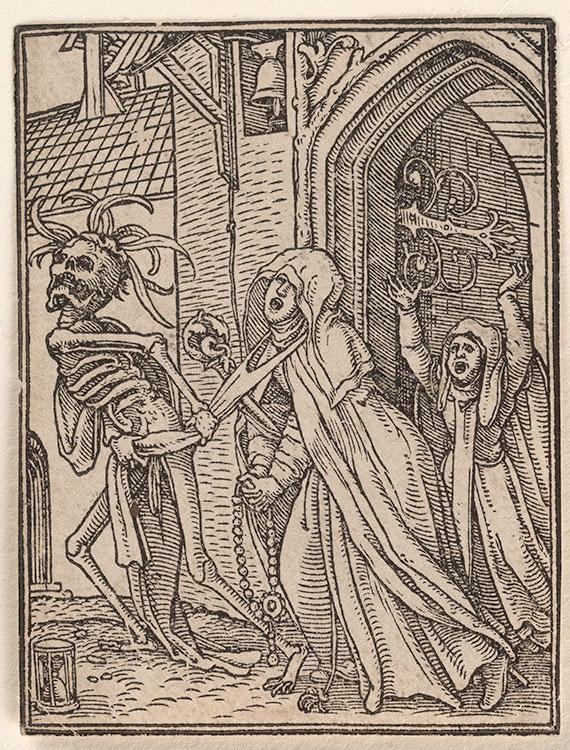

Death and the Abbess

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Abbess, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.15

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Dean (or Canon)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Dean (or Canon), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.16

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

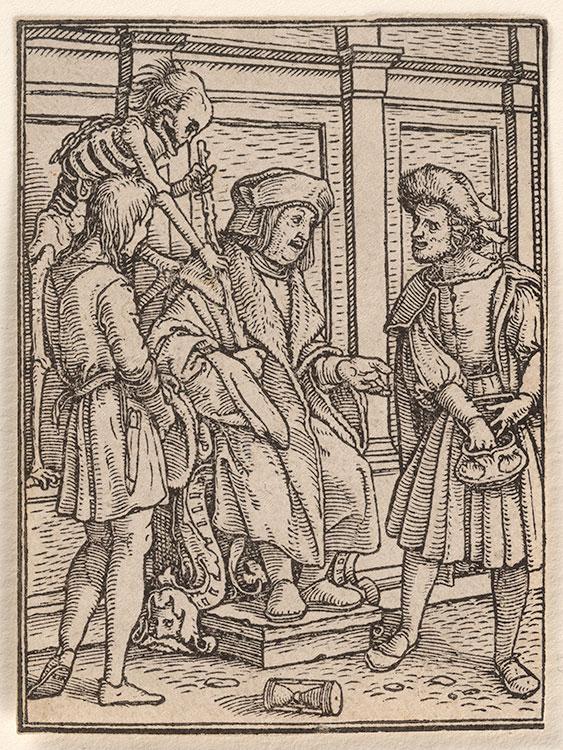

Death and the Judge

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Judge, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.1–40

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

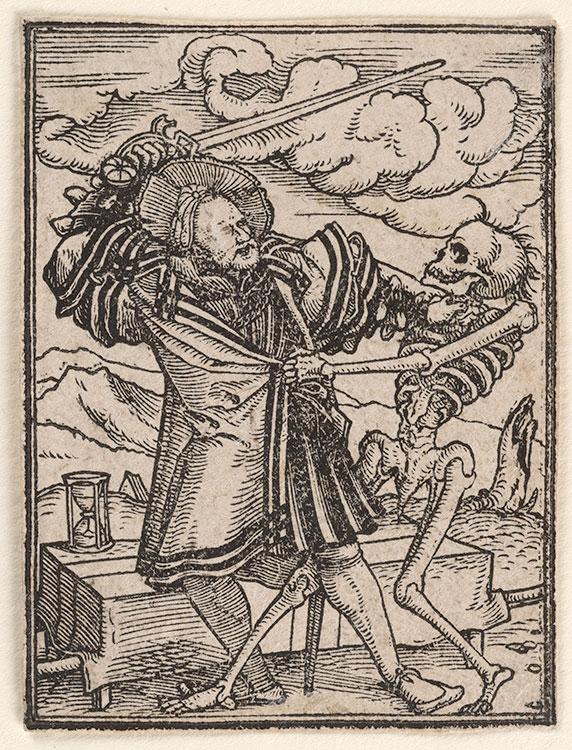

Death and the Nobleman

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Nobleman, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.18

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Lawyer (or Advocate)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Lawyer (or Advocate), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.19

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Councilor

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Councilor, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.20

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Clergyman

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Clergyman, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.21

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

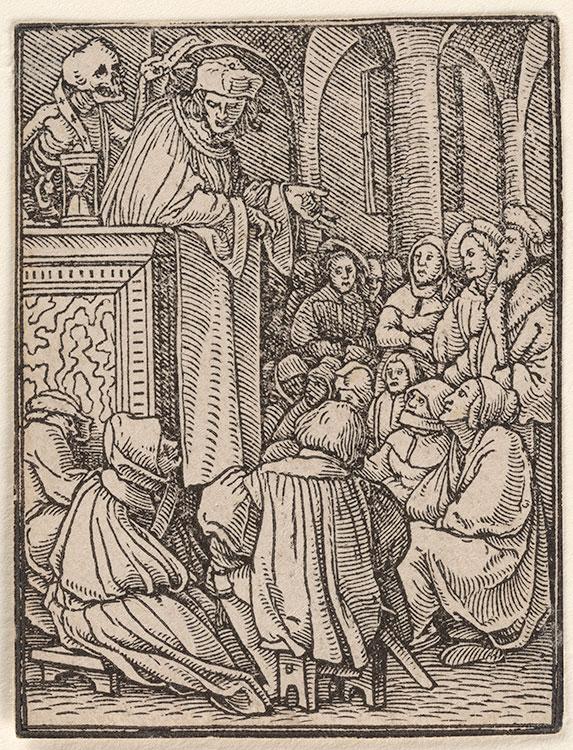

Death and the Priest (or Preacher)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Priest (or Preacher), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.22

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Monk (or Mendicant)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Monk (or Mendicant), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.23

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Nun

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Nun, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.24

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Old Woman

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Old Woman, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.25

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Doctor (or Physician)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Doctor (or Physician), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.26

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Rich Man

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Rich Man, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.27

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

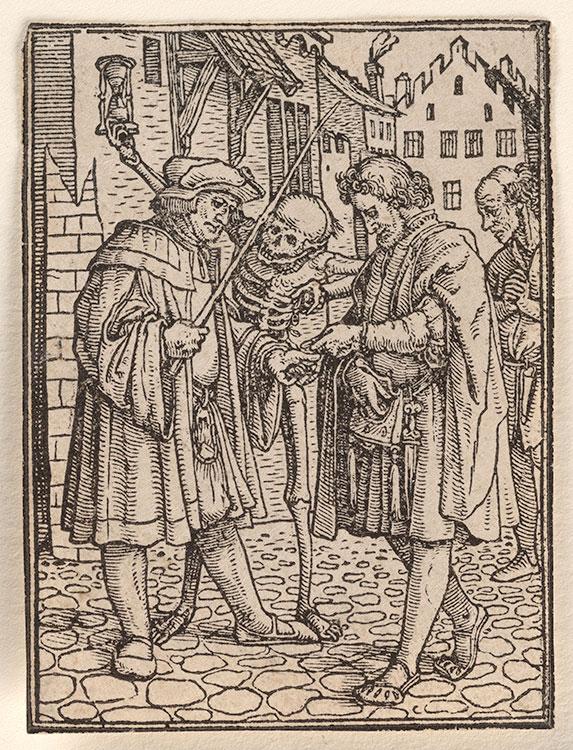

Death and the Merchant

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Merchant, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.28

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Skipper (or Sailor)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Skipper (or Sailor), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.29

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Coat of Arms of Death

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Coat of Arms of Death, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.40

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Child

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Child, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.38

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Count

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Count, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.31

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Countess

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Countess, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.33

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Duchess

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Duchess, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.35

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Knight

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Knight, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.30

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Noblewoman

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Noblewoman, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.34

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Old Man

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Old Man, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.32

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Plowman (or Peasant)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Plowman (or Peasant), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.37

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Death and the Shopkeeper (or Trader)

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Death and the Shopkeeper (or Trader), ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.36

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

The Last Judgment

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

The Last Judgment, ca. 1526

Woodcuts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1919; 19.57.39

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

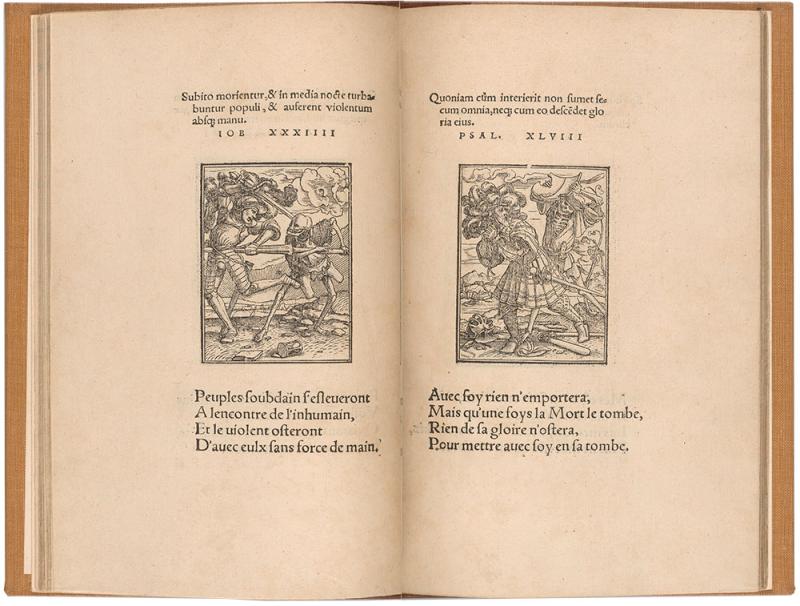

Les simulachres & historiees faces de la mort

Lützelburger and Holbein’s Images of Death series was always intended to illustrate a printed book. The devotional texts were written by the French poets Nicholas Bourbon (whose portrait by Holbein is also on view) and Jean de Vauzelles or Gilles Corrozet. The introduction states that several of the blocks were incomplete when Lützelburger died. The printers failed to find a blockcutter of equal ability to complete the images (ultimately hiring a less skilled artist), which is why the book was not published until 1538, twelve years after Lützelburger’s death. Nevertheless, the edition was hugely successful and reprinted in Lyon into the 1560s. Holbein’s compositions were copied by dozens of printers and artists across Europe into the nineteenth century.

Les simulachres & historiees faces de la mort (The simulated and illustrated faces of death)

Woodcuts by Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Lyon: Melchior and Gaspar Trechsel for Jean and François Frellon, 1538

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased with the De Forest collection, 1899; PML 2112

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan by 1905; PML 2113

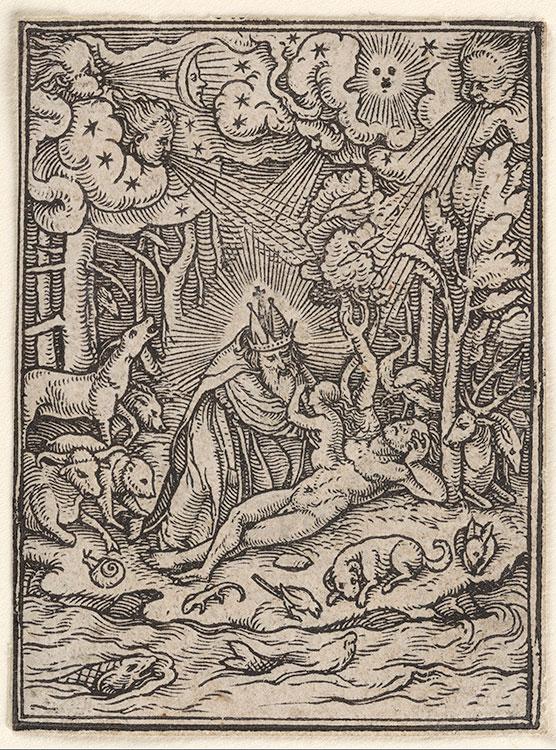

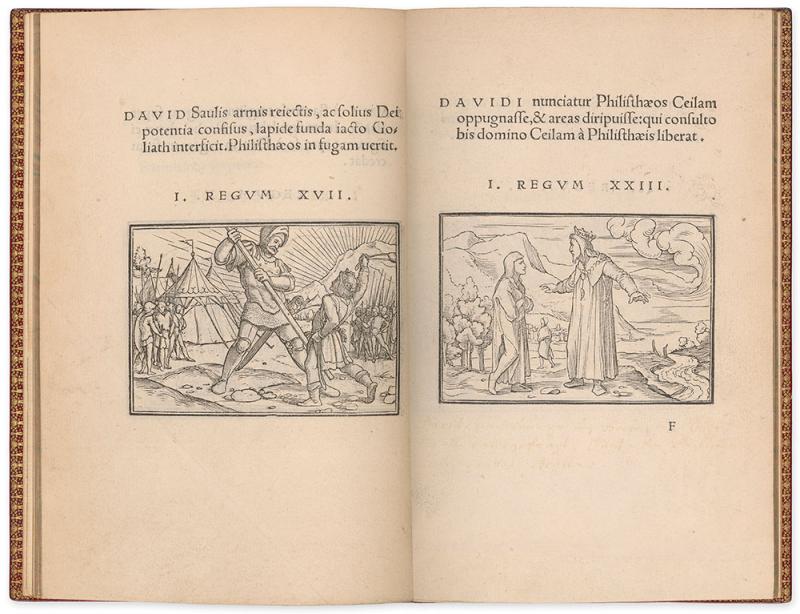

Historiarum veteris instrumenti icones

.jpg)

While producing the Images of Death, Lützelburger and Holbein were also collaborating on a series of illustrations of the Old Testament for the same Lyon printers. Slightly larger than the death scenes, the Old Testament images often feature expansive landscapes reflecting the epic nature of the scriptural narratives. As with the Images of Death, the Old Testament woodblocks were unfinished at Lützelburger’s death; the project was completed by Veit Specklin prior to publication. The woodcuts were used to illustrate this small picture book and a Bible.

Historiarum veteris instrumenti icones ad vivum expressae (Icons of deeds of ancient history represented from life)

Woodcuts by Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526) and Veit Specklin (d. 1550), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Lyon: Melchior and Gaspar Trechsel for Jean and François Frellon, 1538

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased with the De Forest collection, 1899; PML 2126

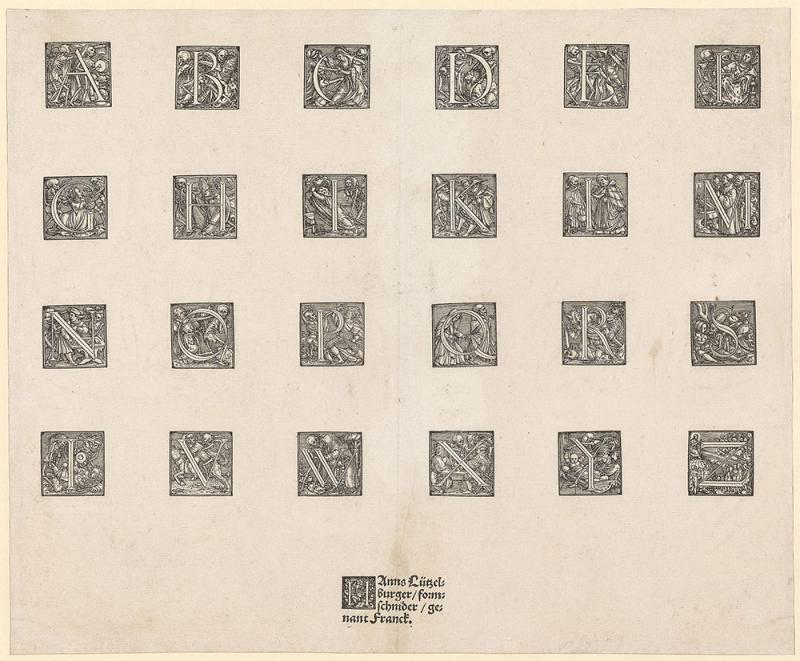

Latin Capital Letter Alphabet (Death Alphabet)

Prior to the Images of Death, Holbein designed a Latin alphabet for Lützelburger that showcased the latter’s dexterity at woodcutting. The minuscule compositions expertly render action, emotion, and three-dimensionality—qualities that the other blockcutters who worked with Holbein could not as effectively achieve. The capital letters were intended to be used in a printed book to begin a paragraph or section of text (what is often called a “drop cap” today). This print was produced as an advertisement for Lützelburger, however, and the letters themselves appeared only in a few books published in Basel during the 1520s and ’30s.

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Latin Capital Letter Alphabet (Death Alphabet), ca. 1523

Woodcut

Inscribed at bottom center, in German: Hans Lützelburger, blockcutter, called Franc [i.e., of French origin]

Kunstmuseum Basel, Kupferstichkabinett, X.228

Battle of the Naked Men and Peasants

Lützelburger had been a blockcutter in Augsburg on several print projects for Emperor Maximilian I. After the Holy Roman emperor’s death in 1519, the imperial workshop closed, and Lützelburger moved to Basel in search of work. Prior to his collaboration with Holbein on the Death Alphabet, Lützelburger produced this sheet (in either Augsburg or Basel) as an advertisement of his abilities engraving the human form, landscape, and text. Lützelburger prominently displayed his name and role (formschneider, meaning “blockcutter”) on the print, while the artist responsible for the design, Hogenberg, is represented with his initials, HN, at the bottom-left corner of the figural composition.

Hans Lützelburger (1495?–1526), after a design by Nikolaus Hogenberg (1500–1539)

Battle of the Naked Men and Peasants, 1522

Woodcut

Inscribed at bottom left, in German: Hans Lützelburger, blockcutter, 1522

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Ruth and Jacob Kainen Memorial Acquisition Fund; 2017.21.1

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Courtiers and Merchants

After returning to England in 1532, Holbein became painter to King Henry VIII and found avid patrons among members of the royal court. Holbein’s drawings of these courtiers, in colored chalks and ink on pink prepared paper, reveal the artist’s close, first-hand study of his sitters’ faces. Paying scrupulous attention to clothing and personal jewels, he portrayed his subjects in a variety of modes and scales, including small portable paintings. Round formats were associated with both classical and Christian conceptions of eternity and thus especially appropriate to a portrait’s commemorative function.

Holbein also depicted members of the Hanseatic League, German merchants residing in an enclave known as the London Steelyard (Stalhof). These portraits may have been sent home to family members, or they may have hung together in the Guildhall of the Steelyard as a statement of corporate identity.

Simon George

Only this sitter’s name and place of origin (Cornwall, in southwest England) are known today. Yet the complex system of symbols that Holbein developed in this work suggests that the young man might have been a poet conversant in the symbolic language of love. He wears a pink jerkin (close-fitting jacket) and a hat badge decorated with the mythological paramours Leda and the Swan. In his right hand, George holds a red carnation—a symbol of affection and betrothal. Other interpretations are also possible: the carnation may signify Christ’s crucifixion, and the pansies decorating the hat could evoke a meditation on mortality. Recent conservation of the panel allows us to fully appreciate Holbein’s vivid colors and rich surface effects—from the carefully modulated description of George’s skin to the black embroidery of his glossy, puckered jacket.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Simon George, ca. 1530–40

Mixed technique on panel

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main; 1065

This is a rare opportunity to see, side by side, Holbein’s preparatory drawing and the finished portrait of one of his most enigmatic English sitters—Simon George of Cornwall. Normally separated between collections in England and Germany, the two works have been temporarily reunited for the purpose of this exhibition, inviting us to explore Holbein’s preparatory process and compare his handling of these two different media.

Holbein established the outline of George’s head and defined his facial features in the drawn study. The hat and the costume were worked out in much greater detail in the painted roundel. The painting also differs from the drawing in the greater fullness of the sitter's beard.

Notably, the drawing focuses only on Simon George’s head and does not include his right hand, which features prominently in the finished panel. This was Holbein’s standard working procedure. The artist likely made an additional drawing for the hand holding the red carnation, although no such work is known to survive.

Photo: Städel Museum

Simon George

Holbein drew this image from life, in preparation for the corresponding painted roundel portrait. He employed a delicately layered technique to capture the profile of Simon George of Cornwall, going as far as describing individual wispy hairs that form the sitter’s eyebrow and stubble. Established through the initial sketch, the contour of the head and the facial features could be carried to the painted portrait by tracing outlines onto a panel using paper blackened with chalk. Changes to the composition could be introduced at this stage. In this case, Holbein replaced the stubble on George’s chin with a full beard in the painting, perhaps in accordance with court fashion.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Simon George, ca. 1535

Black and colored chalks, pen and brush and black ink, and metalpoint on pink prepared paper

Lent by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II; RCIN 912208

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

A Court Official and his Wife

This pair of intimate roundels might originally have had protective lids (like Holbein’s painting of Philip Melanchthon, also on view), or the panels could have been brought together to form a portable capsule. Compact and more affordable than larger-scale likenesses, the portraits are no less refined and detailed than Holbein’s grander works. The man is dressed in royal livery: a red coat decorated with the elaborately embroidered initials H and R, for Henricus Rex, referring to King Henry VIII. The uniform indicates that the subject served the court in an official capacity. The woman’s relatively demure costume allowed Holbein to explore a variety of textures, such as the thick felt or wool bonnet and the fur trimming of her dress.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

A Court Official of Henry VIII

The Wife of a Court Official of Henry VIII

1534

Oil on panels

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Gemäldegalerie; 5432 and 6272

KHM-Museumsverband

Martin Luther and Katharina von Bora

At the wedding of the German theologian and reformer Martin Luther (1483–1546) and Katharina von Bora (1499–1552) on 13 June 1525, the artist Lucas Cranach presented the couple with a pair of small, round portraits. He and his workshop then produced several copies for the couple’s close friends and relatives. Cranach’s and Holbein’s roundels reflect the popularity of this format in the early sixteenth century and emphasize the portrait’s importance as a gift that commemorated an event or intimate connection.

Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553)

Martin Luther and Katharina von Bora, 1525

Oil on panels

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909; AZ038

Portrait of a Woman

Compared to most likenesses in the exhibition, this portrait is relatively plain, without prominent attributes that might help reveal the sitter’s identity. Nevertheless, the woman’s status and wealth are indicated through Holbein’s attention to minute details, such as her ornate rings and the pearl-headed pins that attach her bonnet to her cap and close the translucent cambric at her neck. Her costume resembles that of the younger woman in the small roundel portrait, also included in the exhibition, suggesting that this sitter might also have been the wife of an English court official. The woman’s sullen demeanor is underscored by her tense posture and tightly clasped hands, as well as the downturned corners of her mouth..

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Portrait of a Woman, 1532–34

Oil and tempera on panel

Detroit Institute of Arts, bequest of Eleanor Clay Ford; 77.81

.

Derick Berck of Cologne

Derick Berck, a Hanseatic merchant, gazes warmly at the viewer. His name appears on the folded paper he holds, above his merchant’s mark. The small sheet at left quotes a passage from the ancient Roman poet Virgil, which urges Berck and his descendants—and perhaps the viewer—to be steadfast and courageous in business and life. This statement might have been the sitter’s personal motto. Holbein created a sense of pictorial space by positioning Berck between a table, covered with a red cloth, and a green curtain with a hanging cord. The latter motif recalls the background in the portrait of Sir Thomas More that Holbein made almost a decade earlier, also on view in the exhibition.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Derick Berck of Cologne, 1536

Oil on canvas, transferred from panel

Inscribed on lower right, in Latin: The year 1536 at the age of 30

Inscribed on the small piece of paper at left, in Latin: [Perchance even this distress] will someday be a joy to recall (Virgil, Aeneid, I.203)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jules Bache Collection, 1949; 49.7.29

A Member of the Wedigh Family

Like the two other images of Hanseatic merchants here and here, this portrait eliminates all references to the sitter’s activities in trade and commerce. Instead, it emphasizes his familial associations. The man holds folded gloves and wears a signet ring bearing the coat of arms of the Cologne-based Wedigh family (a black chevron surrounded by three green willow leaves), which partially reveals his identity. Holbein animated the still frontal likeness by slightly enlarging the man’s right eye and raising his right eyebrow. The inscription in the background states the work’s date and the age of its subject. Such refined lettering in Roman capitals had become a standard practice in Holbein’s portraiture by the early 1530s.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

A Member of the Wedigh Family, 1533

Oil on panel

Inscribed on the background, in Latin: The year 1533 / At the age of 39

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie; 586B

In addition to scholars, members of the royal family and Tudor courtiers, Holbein portrayed foreign diplomats and German merchants of the Hanseatic League based in London. The artist, who was born in Germany and spoke the language, seems to have developed a particularly close working relationship with his merchant countrymen. Based in the Stalhof, or Steelyard, on the north bank of the river Thames, members of the guild appear in seven surviving portraits painted by Holbein.

This panel is one of the finest and best preserved portraits in the group. Although the man’s name is no longer known to us, the coat of arms of the Cologne-based Wedigh family, visible on his prominently placed signet ring, partially reveals his identity. The frontal pose and direct gaze result in a strikingly forthright image. This approach differentiates portraits of members of the Hanseatic League from likenesses of Holbein’s English sitters, who seem to have preferred to be portrayed in three-quarter or profile views.

Image: bpk Bildagentur / Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin / Photo: Jörg P. Anders / Art Resource, NY.

Portrait of a Hanseatic Merchant

Although this sitter elected to be portrayed with no identifying attributes, his sober attire—a black gown over a black doublet with satin sleeves and a high-collared white shirt tied at the neck— suggests that he was a member of the Hanseatic League. The work was painted on the occasion of the man’s thirty-third birthday. Reaching this number of years often led to commemorative portrait commissions, as it was the age at which Christ was believed to have been crucified.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Portrait of a Hanseatic Merchant, 1538

Oil on panel

Inscribed on the background, in Latin: The year of Our Lord 1538 / At the age of 33

Yale University Art Gallery, gift of Charles S. Payson, B.A. 1921; 1977.187

Portrait of a Man (Jan Jacobsz. Snoeck?)

Netherlandish painter Jan Gossaert portrayed this merchant within a busy, enclosed space, surrounded by tools of his trade—an inkpot and quill pens, a talc shaker for drying ink, and a pair of scales for weighing coins. In sumptuous attire, the young man radiates self-assurance. Holbein likely encountered Gossaert’s work in 1532, when he was passing through the Netherlands on his way to England for the second time. Although the character of this portrait is very different from Holbein’s other depictions of members of the Hanseatic League, scholars have argued that the painting directly influenced his likeness of the merchant Georg Gisze, now in Berlin.

Jan Gossaert (ca. 1478–ca. 1532)

Portrait of a Man (Jan Jacobsz. Snoeck?), ca. 1530

Oil on panel

Inscribed on the paper at left, in Dutch: Miscellaneous letters

Inscribed on the paper at right, in Dutch: Miscellaneous drafts

Inscribed on a ring on the index finger: IS

Inscribed on the hat badge: IAS (in ligature)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund; 1967.4.1

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Portrait of a Scholar or Cleric

Like all portrait drawings that Holbein made during his later years in England, this work is relatively small and on paper toned with a light-pink ground. The pink preparation allowed Holbein to efficiently render his White European sitters’ complexions by adding lighter and darker colors to its warm-hued middle tone. Although this man’s identity is unknown, the felt cap and hooded robe suggest that he was a scholar or cleric. Now in the collection of the Getty Museum, this is the only portrait drawing securely attributed to Holbein in the United States.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Portrait of a Scholar or Cleric, 1532–35

Black and red chalks, and pen and brush and black ink on pink prepared paper

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; 84.GG.93

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Nicholas Bourbon

Nicholas Bourbon (ca. 1503–1549/50), a poet and humanist in the court of Henry VIII, was a friend and admirer of Holbein’s, marveling at the lifelikeness of the artist’s portraits in his verses. In this work, which served as a preparatory study for a woodcut illustrating Bourbon’s Paidagogeion— a didactic poem influenced by the writings of Erasmus—Holbein turned his gaze toward the poet himself. Bourbon holds a quill pen in his quickly sketched right hand, as if actively composing. In keeping with his friend’s interest in Greek and Roman culture, Holbein portrayed him in profile, reminiscent of an ancient coin.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Nicholas Bourbon, 1535

Black and colored chalks, and pen and black ink on pink prepared paper

Lent by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II; RCIN 912192

Poet Nicholas Bourbon arrived in England in 1535, after being exiled from his native France on account of his Protestant sympathies. He soon entered the Tudor court, where he was closely aligned with Anne Boleyn, the second wife of King Henry VIII. It was at this time that Bourbon first met Hans Holbein, who had been recently appointed as a royal painter. In a prefatory letter included in his didactic poem Paidagogeion, Bourbon lists the artist among the friends he made at the English court and compares him to the renowned ancient painter Apelles.

In this portrait, Holbein depicts Bourbon in profile view and with a pen in hand, as if caught in the act of composing one of his poems. The image emphasizes the poet’s intellectual and creative abilities and recalls Holbein’s earlier portraits of scholars—most notably, Erasmus—at work. It is unclear whether Holbein intended to use this study to make a painted likeness. However, we know that the sheet served as a model for the woodcut portrait of Bourbon, included in the first edition of Paidagogeion.

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

Expression through Ornament

In addition to painting portraits and designing prints, Holbein composed small ornamental patterns and allegorical images for fabrication by goldsmiths. Holbein’s drawings in pen and wash presented plans for intricate pendants, hat badges, clasps, and gold-and-enamel book covers that adopted patterns and motifs popular in English and European decorative arts. Noble, wealthy individuals commissioned jewels and wore them prominently as expressions of their status and erudition. Many jewels featured emblems, also known as devices—motifs that served as visual representations of aspirations and values. Although no jewels designed by Holbein survive today, sixteenth-century French and English pendants and hat badges, on view here, demonstrate the sophistication and finesse of these precious objects.

This section also features An Allegory of Passion—a large, enigmatic painting whose lozenge format is unique in Holbein’s oeuvre. The work draws on the artist’s talent for ornaments and emblems and might have been created for a courtier with an interest in the poetry of Francesco Petrarch, the fourteenth-century Italian writer and scholar.

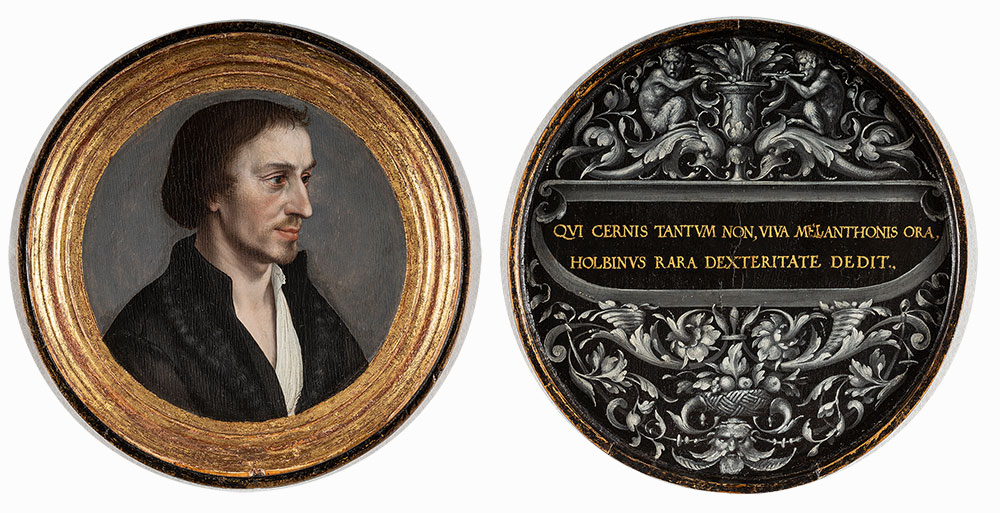

Philip Melanchthon

This portrait of Philip Melanchthon (1497–1560), the famous Protestant reformer, recalls the images of erudite men that Holbein painted during his years in Basel. Holbein never met Melanchthon and probably relied on a print as the basis for the likeness. This is the only known complete kapselbild (portrait with a lid) by the artist, and its inscription asserts that Holbein’s art rivals nature, a well-known theme from antiquity that would have appealed to Melanchthon as well as to the recipient of this object. Given its elaborate decoration and sophisticated theme, the piece may have been intended as a gift for someone of high status, perhaps even King Henry VIII of England.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Philip Melanchthon, ca. 1535

Oil on panel, with lid

Inscribed inside the lid, in Latin: Behold Melanchthon’s features, almost as if alive: Holbein has captured them, with the utmost skill.

Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover; PAM 798

Niedersachsisches Landesmuseum, Hannover

Portrait of an English Lady

This likeness conveys the poise of a woman of distinction, probably a member of the English court. The sitter’s serene features are balanced by the emphatic yet decorous gesture of her clasped hands. Holbein’s sumptuous palette and use of gold—on her fashionable French hood, the gleaming jeweled medallion affixed to her gown, and even the tiny pin fastening her black sleeve— date this portrait to the last years of his career but provide no clues to the sitter’s identity. The medallion, which shows two figures standing on either side of a fire, might represent an Old Testament scene.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Portrait of an English Lady, ca. 1540–43

Oil on panel

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Gemäldegalerie; 847

KHM-Museumsverband

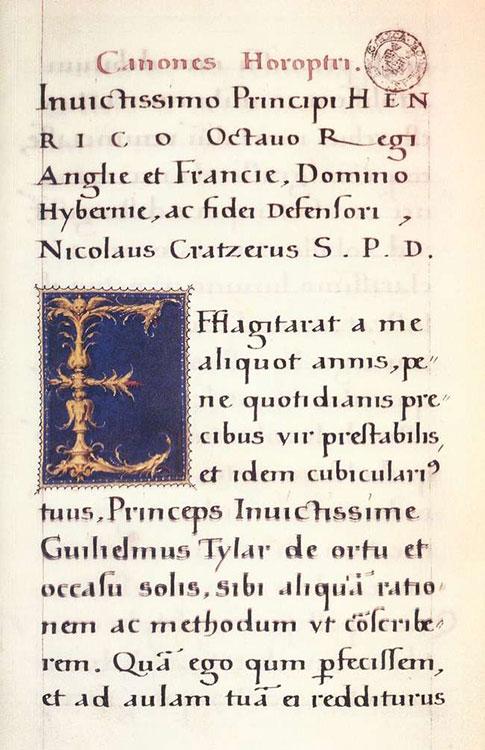

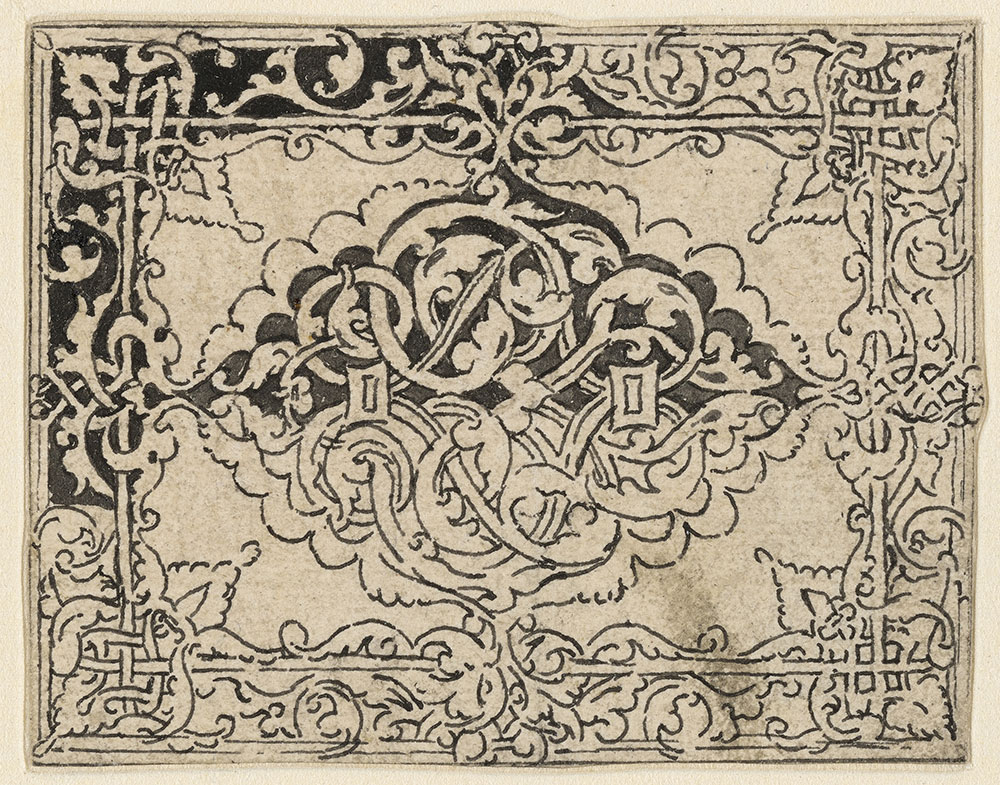

Canones horopteri

This is the only known manuscript illumination by Holbein. The animal and foliate forms of the letter E recall his designs for woodcut letters as well as for jewelry and metalwork. The illumination decorates the beginning of a manual for using an astronomical instrument (the horopterum) to determine the times of sunrise and sunset. The author was the royal astronomer Nicholas Kratzer, whose portrait Holbein painted in 1528 (now at the Louvre, Paris). Kratzer dedicated this manuscript to King Henry VIII, who was keenly interested in scientific pursuits, and likely presented it to the king as a New Year’s gift.

Nicholas Kratzer (1487–1550)

Canones horopteri, 1528–29

Written by Pieter Meghen (1466/67–1540)

Illuminated by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Manuscript on parchment

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford; MS. Bodl. 504, fol. 1r

Tantalus

This assured drawing, tinted with watercolor and touches of gold to guide the application of enamel by a goldsmith, is one of Holbein’s most finished designs for a hat badge or medallion. It focuses on the tale of Tantalus, who, according to Greek mythology, was eternally punished by Zeus for abusing the hospitality of the gods. Trapped in a pool beneath an apple tree, Tantalus (the source of the word “tantalize”) strains upward yet cannot reach the fruit to satisfy his hunger. Although he is in undulating water, Tantalus also is not allowed to quench his thirst. Despite its minute scale, the complex composition fully conveys the drama of the story.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Tantalus, 1535–40

Pen and black ink and watercolor, heightened in gold

Inscribed on the scroll, at top: Tantalus

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann and Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 1998; 1998.18.1

According to surviving inventories, Henry VIII and his courtiers owned large amounts of precious metalwork. These included medallions, hat badges, rings and other jewels made of silver, gold and enamel. As you move through this final room, you will notice that such intricate, elegant objects feature prominently in Holbein’s English portraits, adorning the woman from the Cromwell family in the picture from the Toledo Museum of Art and the unknown English Lady in the panel from Vienna.

This drawing is one of Holbein’s most finished compositions for a hat badge or medallion. Like many of the artist’s jewel designs, it features a story from classical mythology. Tantalus, who abused the hospitality of the gods, is punished by Zeus for his greed and doomed to be forever hungry and thirsty. Such an object might have been commissioned and worn by a wealthy individual as an expression of his or her taste and erudition, or a visual satire: a lavish jewel warning against excess.

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

William Parr, Marquess of Northampton

William Parr (1513–1571) was the brother of Catherine Parr, the sixth and final wife of King Henry VIII. Renowned for his taste and good looks, Parr is shown wearing a fur-edged gown made of white and purple velvet and satin (as indicated by the artist’s inscriptions). Also included are quick sketches showing details of various jewels that he supposedly wore. The object at upper left probably depicts St. George and the Dragon, likely a reference to George as a patron saint of the chivalric Order of the Garter, to which Parr belonged. Below, Holbein included a study of a jewel inscribed with the word MORS (death), probably part of a longer motto or device.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

William Parr, Marquess of Northampton, 1538–42

Black and colored chalks, white opaque watercolor, pen and black ink, and brush and ink on pink prepared paper