During the first half of the cinquecento, Domenico Beccafumi came to prominence as a talented painter, sculptor, engraver, miniaturist, and draftsman in his native Siena, a city he almost never left. “He was not much used to making journeys,” Vasari records in his Vite, and “excusing himself for this to many of his friends, and particularly on one occasion to Giorgio Vasari, said that since he was away from the air of Siena . . . he did not seem to be able to do anything.”1

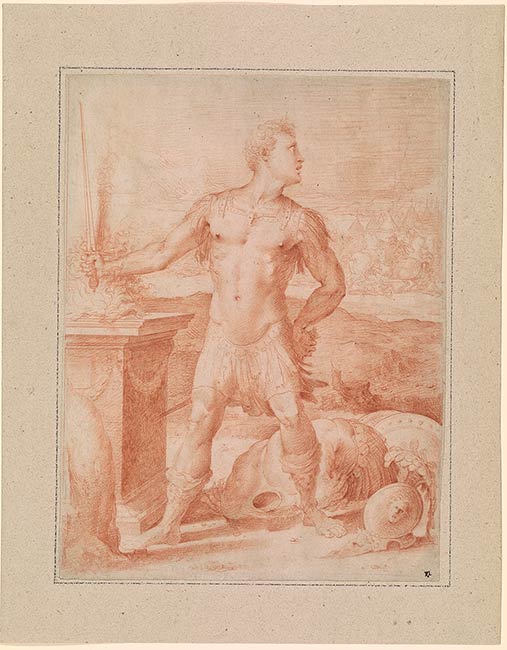

Nearly two hundred sheets are today attributed to the artist. Of these, Gaius Mucius Scaevola Holding His Hand in the Fire must be considered a unicum, as no other drawing in the whole Beccafumi graphic oeuvre reaches the same level of exquisite finish. Because of its stylistic and technical character, the Morgan’s drawing has been extensively discussed by critics, who have long disagreed on both its chronology and function. Jacob Bean and Felice Stampfle first suggested that the sheet was produced as a preparatory study for an engraving, but De Marchi more plausibly suggested that it was made as a finished presentation drawing to be kept by a patron or given as a gift.2 In this regard, it has been noted that, like other finished chalk drawings by the artist, the Morgan’s bears traces of preliminary marking with a stylus— clearly visible along the right edge of the cuirass, under the breastbone, and at the backs of Mucius Scaevola’s feet— indicating the extreme care that went into the preparation of the drawing. The stylus marks, as well as the work’s execution on a large sheet of high quality paper and its careful refinement in every detail, support the hypothesis that the work was intended as a finished presentation drawing, similar to those that Michelangelo Buonarroti drew for his friends and close acquaintances.

Initially connected by Sanminiatelli to Beccafumi’s frescoes in the Palazzo Venturi in Siena (also known as Palazzo Bindi-Sergardi; ca. 1524–25) and therefore considered an early work by the artist, the sheet was probably drawn at a more mature stylistic phase, around the late 1530s, as suggested by some of the formal elements that characterize the picture—the hyperdecorative motifs of the hero’s helmet and greaves, for example. Additionally, the watermark located in the right side of the sheet at center is common to paper produced between 1535 and 1543, further arguing for a later date for the drawing.

The sheet depicts an episode from Livy’s history of Rome (Ab Urbe Condita, 2:XII–XIII). While Rome was under siege by the Etruscan army of King Porsena, the young Roman nobleman Gaius Mucius slipped into the enemy camp with the intent to assassinate Porsena but mistakenly killed his scribe. Captured and threatened with being roasted alive, he thrust his right hand into the fire as a proof of courage and held it there without giving any indication of pain, thereby earning the cognomen Scaevola, meaning “left-handed.” Shocked at the youth’s bravery, the Etruscan king released Gaius Mucius from the camp and allowed him to return to Rome. The entire space of the sheet is occupied by the main episode of Livy’s story, although an allusion to the war between the Roman and the Etruscan army appears in the far background, where Porsena’s camp, as well as a group of battling cavalrymen, is depicted. When Beccafumi conceived this secondary scene, he probably had in mind Leonardo’s cartoon for the celebrated Battle of Anghiari (1506–8), which he easily could have studied in nearby Florence. The animated collision of the horsemen staged on the back of the composition seems in fact to emerge directly from Leonardo’s invention.3

It must also be noted that the figure of Mucius Scaevola in the Morgan drawing presents evident affinities with Leonardo’s unrealized statue of Hercules, which the latter was supposedly designing in Florence during the late phase of work on the cartoon and mural of the Battle of Anghiari.4 As it can be seen in one of Leonardo’s few surviving exploratory studies for the sculpture (Biblioteca Reale, Turin, inv. 15630), the nude Hercules was represented holding a club, with his legs slightly spread and his head turned to the side. Leonardo’s invention was also Beccafumi’s inspiration for a pen-and-ink drawing now at the Louvre in which the demigod appears seen from the back (Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. 255bis).5 Turning the figure of Hercules, Beccafumi modeled the silhouette of Mucius Scaevola for the present drawing.

The artist seemed particularly intrigued by the character of Mucius Scaevola, and another sheet in the Morgan’s collection includes further investigation of the figure (1964.14). The pose of the protagonist (except for the left arm, shown bent and placed on the hip) differs substantially from that of Mucius Scaevola as depicted in the present drawing. The motif of the altar seen at an angle recurs in both works, however, suggesting that the artist explored other possible solutions before conceiving the final design of the scene as it appears in the highly finished red-chalk drawing.

—MSB

Footnotes:

- Vasari 1996, 2:200 and 201; Vasari 1878–85, 5:650.

- For Bean and Stampfle, see New York 1965– 66, no. 64; for De Marchi, see Siena 1990, no. 132.

- An echo of Leonardo’s art—and in particular of his lost Florentine fresco—has been detected in other works by Beccafumi, specifically in the Death of Cato and in the Sacrifice of Codrus, painted in the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, in which the rampant knights also recall Leonardo’s cavalrymen in the Battle of Anghiari.

- On the statue of Hercules and Leonardo’s design, see New York 2003, nos. 101–3.

- See Paris 2009, no. 19.

Inscribed on verso, at lower right, in pen and brown ink, "Domenico Beccafumo detto Meccarino / 2.4".

Watermark: Anvil and hammer inside a circle, centered on chain line (Briquet 5964: Sienna 1535-1543).

Lely, Peter, Sir, 1618-1680, former owner.

Isaacs, J. (Jacob), 1896-1973, former owner.

Calmann, Hans M., 1899-1982, former owner.

Rhoda Eitel-Porter and and John Marciari, Italian Renaissance Drawings at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, 2019, no. 92.

Selected references: New York 1965-66, no. 64; Vitzhum 1966, 110; Fellows Report 14 1967, 100-102; Sanminiatelli 1967, no. 76; Avery 1972, 103; Providence 1973, no. 14; Northampton 1978, no. 104; Gordley 1988, 288, 339, no. 85, under no. 95; Siena 1990, no. 132; Torriti 1998, no. D76, and under no. D92; Lincoln 2000, 96; London 2007-8, no. 113; Paris 2009, under no. 8.

Pierpont Morgan Library. Review of Acquisitions, 1949-1968. New York : Pierpont Morgan Library, 1969, p. 130.

Adams, Frederick B., Jr. Fourteenth Annual Report to the Fellows of the Pierpont Morgan Library, 1965 & 1966. New York : Pierpont Morgan Library, 1967, p. 100.