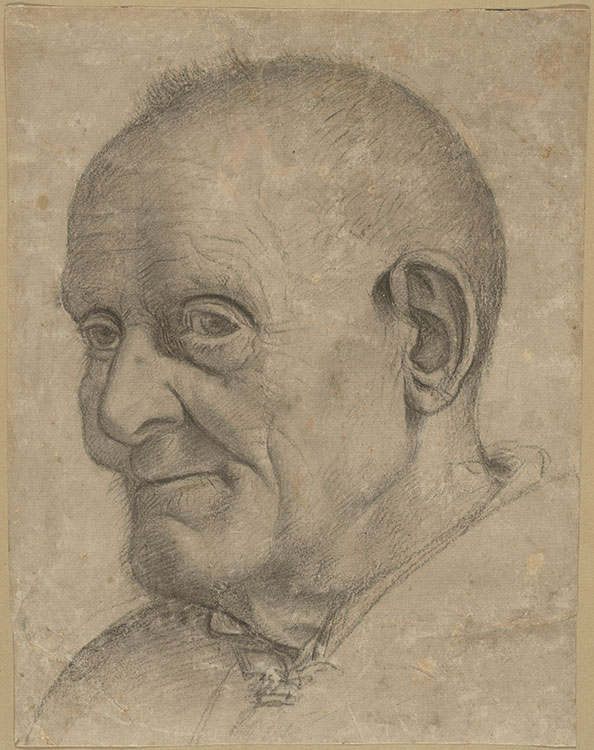

This moving portrait of an older man was made in northern Italy, probably in the 1490s. The man’s pensive gaze suggests an introspective mood. His unshaven chin, wrinkled flesh, sunken cheeks and eyes, and thinning hair are rendered attentively, with uncompromising naturalism—evidence of the artist’s earnest inquiry into the aging process. The skillful application of charcoal—which ranges from bold, velvety lines to very light hatches, blended with a stump and brush—creates a convincing impression of plasticity and volume.

Attributed to Francesco Bonsignori

Italian, ca. 1455–1519

Portrait of an old man, late fifteenth century

Charcoal, with wet brush and stumping, on tan paper prepared with a gray ground

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.834

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Ian Hicks: The author of this sensitive portrait remains open to question. Scholars generally agree that it dates from the late 15th century, but different artists or artistic circles have been proposed. Most recently, an attribution to Francesco Bonsignori has been advanced. The most gifted member of an artistic family, Bonsignori spent his early career working in his native Verona before relocating to Mantua in 1492 to work at the Gonzaga Court. In forging his artistic identity, the artist drew inspiration from Giovanni Bellini and Andrea Mantegna, among others. To complicate matters, the comparable study behind this drawing's attribution to Bonsignori has itself oscillated under these different names. Attributional questions aside, the drawing is remarkable for its attentive descriptions of texture, particularly the sitter's creased and folded skin, and his wispy hair and beard. The artist was concerned with describing the play of light over the compelling topography of the man's face. The drawing's detailed characterization and unmediated naturalism strongly suggest that the artist made this study directly in front of the kindly sitter. There is nothing in this portrait to indicate the grandeur of courtly status, and the artist may have made it on his own initiative, like the nearby study by Honoré Daumier.